On 21 August 2017, the Great American Eclipse caused a diagonal swathe of darkness to fall across the United States from Charleston, South Carolina on the East Coast to Lincoln City, Oregon on the West. In Manhattan, which was several hundred miles outside the path of totality, a gentle gloom fell over the city. Yet still office workers emptied out onto the pavements, wearing special paper glasses if they had been organised; holding up their phones and blinking nervously if they hadn't. Despite promises that it was to be lit up for the occasion, there was no discernible twinkle from the Empire State Building; on Fifth Avenue, the darkened glass façade of Trump Tower grew a little dimmer. In Central Park Zoo, where children and tourists brandished pinhole cameras made from cereal boxes, Betty, a grizzly bear, seized the opportunity to take an unscrutinised dip.

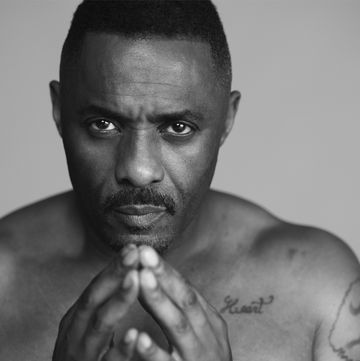

Across the East River in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Oscar Isaac, a 38-year-old Guatemalan-American actor and one of the profession's most talented, dynamic and versatile recent prospects, was, like Betty, feeling too much in the sun. It was his day off from playing Hamlet in an acclaimed production at the Public Theater in Manhattan and he was at home on vocal rest. He kept a vague eye on the sky from the balcony of the one-bedroom apartment he shares — until their imminent move to a leafier part of Brooklyn — with his wife, the Danish documentary film-maker Elvira Lind, their Boston Terrier French Bulldog-cross Moby (also called a "Frenchton", though not by him), and more recently, and to Moby's initial consternation, their four-month-old son, Eugene.

Plus, he's seen this kind of thing before. "I was in Guatemala in 1992 when there was a full solar eclipse," he says the next day, sitting at a table in the restaurant of a fashionably austere hotel near his Williamsburg apartment, dressed in dark T-shirt and jeans and looking — amazingly, given his current theatrical and parental commitments — decidedly fresh. "The animals went crazy; across the whole city you could hear the dogs howling." Isaac happened to be in Central America, he'll mention later, because Hurricane Andrew had ripped the roof off the family home in Miami, Florida, while he and his mother, uncle, siblings and cousins huddled inside under couches and cushions. So yes, within the spectrum of Oscar Isaac's experiences, the Great American Eclipse is no biggie.

Yet there is another upcoming celestial event that will have a reasonably significant impact on Isaac's life. On 15 December, Star Wars: The Last Jedi will be released in cinemas, which, if you bought a ticket to Star Wars: The Force Awakens — and helped it gross more than $2bn worldwide — you'll know is a pretty big deal. You'll also know that Isaac plays Poe Dameron, a hunky, wise-cracking X-wing fighter pilot for the Resistance who became one of the most popular characters of writer-director JJ Abram's reboot of the franchise thanks to Isaac's charismatic performance and deadpan delivery (see his "Who talks first?" exchange with Vader-lite baddie Kylo Ren: one of the film's only comedic beats).

And if you did see Star Wars: The Force Awakens you'll know that, due to some major father-son conflict, there's now an opening for a loveable, rogueish, leather-jacket-wearing hero… "Heeeeeh!" says Isaac, Fonzie-style, when I say as much. "Well, there could be, but I think what [The Last Jedi director] Rian [Johnson] did was make it less about filling a slot and more about what the story needs. The fact is now that the Resistance has been whittled to just a handful of people, they're running for their lives, and Leia is grooming me — him — to be a leader of the Resistance, as opposed to a dashing, rogue hero."

While he says he has "not that much more, but a little more to do" in this film, he can at least be assured he survives it; he starts filming Episode IX early next year.

If Poe seems like one of the new Star Wars firmament now — alongside John Boyega's Finn, Daisy Ridley's Rey and Poe's spherical robot sidekick BB-8 — it's only because Isaac willed it. Abrams had originally planned to kill Poe off, but when he met Isaac to discuss him taking the part, Isaac expressed some reservations. "I said that I wasn't sure because I had already done that role in other movies where you kind of set it up for the main people and then you die spectacularly," he remembers. "What's funny is that [producer] Kathleen Kennedy was in the room and she was like, 'Yeah, you did that for us in Bourne!'" (Sure enough, in 2012's Bourne Legacy, Jeremy Renner's character, Aaron Cross, steps out of an Alaskan log cabin while Isaac's character, Outcome Agent 3, stays inside; a few seconds later the cabin is obliterated by a missile fired from a passing drone.)

This ability to back himself — judiciously and, one can imagine after meeting him, with no small amount of steely charm — seems to have served Isaac well so far. It's what also saw him through the casting process for his breakthrough role in Joel and Ethan Coen's 2014 film Inside Llewyn Davis, about a struggling folk singer in Sixties New York, partly based on the memoir of nearly-was musician Dave Van Ronk. Isaac, an accomplished musician himself, got wind that the Coens were casting and pestered his agent and manager to send over a tape, eventually landing himself an audition.

"I knew it was based on Dave Van Ronk and I looked nothing like him," says Isaac. "He was a 6ft 5in, 300lb Swede and I was coming in there like… 'Oh man.'" But then he noticed that the casting execs had with them a picture of the singer-songwriter Ray LaMontagne. "Suddenly, I got some confidence because he's small and dark so I said to the casting director, 'Oh cool, is that a reference?' And they were like, 'No, he just came in here and he killed it.'" Isaac throws his head back and laughs. "They literally said, 'He killed it.' It was so good!"

In the end it was Isaac who killed it in Inside Llewyn Davis, with a performance that was funny, sad, cantankerous and moving. The film was nominated for two Oscars and three Golden Globes, one of them for Isaac in the category of :"Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture — comedy or musical" (he lost to Leonardo DiCaprio for The Wolf of Wall Street). No cigar that time, but in 2016 he won a Golden Globe for his turn as a doomed mayor in David Simon's HBO drama, Show Me a Hero. This year, and with peculiar hillbilly affectation, Vanity Fair proclaimed Isaac "the best dang actor of his generation". It is not much of a stretch to imagine that, some day very soon, Isaac may become the first Oscar since Hammerstein to win the award whose name he shares. Certainly, the stars seem ready to align.

Of course, life stories do not run as neatly as all that and Isaac's could have gone quite differently. He was born Óscar Isaac Hernández Estrada in Guatemala City, to which his father, Óscar, now a pulmonologist, had moved from Washington DC in order to attend medical school (having escaped to the States from Cuba just before the revolution) and where he met Isaac's mother, Eugenia. Five months after Isaac was born, the family — also including an older sister, Nicole, and later joined by a younger brother, Michael — moved to America in order for Óscar Senior to complete his residencies: first to Baltimore, then New Orleans, eventually settling in Miami when Isaac was six.

Miami didn't sit entirely right with him. "The Latin culture is so strong which was really nice," he says, "but you had to drive everywhere, and it's also strangely quite conservative. Money is valued, and nice cars and clothes, and what you look like, and that can get sort of tedious." Still it was there, aged 11, that he took to the stage for the first time. The Christian middle school he attended put on performances in which the kids would mime to songs telling loosely biblical stories, including one in which Jesus and the Devil take part in a boxing match in heaven (note the word "loosely"). For that one, Isaac played the Devil. In another, he played Jesus calling Lazarus from the grave. "So yeah," he laughs, "I've got the full range!'

He enjoyed the mixture of the attention and the "extreme nature of putting yourself out there in front of a bunch of people", plus it gave him some release from stresses at home: his parents were separating and his mother became ill. His school failed to see these as sufficiently mitigating factors for Isaac's subsequent wayward behaviour and, following an incident with a fire extinguisher, he was expelled. "It wasn't that bad. They wanted me out of there. I was very happy to go."

Following his parents' divorce, he moved with his mother to Palm Beach, Florida, where he enrolled at a public high school. "It was glorious, I loved it," says Isaac. "I loved it so much. I could walk to the beach every day, and go to this wild school where I became friends with so many different kinds of people. I met these guys who lived in the trailer parks in Boynton Beach and started a band, and my mom and my little brother would come and spy on me to see if I was doing drugs or anything, and I never was."

Never?

"No, because I didn't drink till I was, like, 24. Even though I stopped being religious, I liked the individuality of being the guy who didn't do that stuff. Maybe it was the observer part of me… I liked being a little bit detached, and I wasn't interested in doing something that was going to make me lose control."

When he was 14, Isaac and his band-mates played at a talent show. They chose to perform 'Rape Me' by Nirvana. "I remember singing to the parents, 'Rape meeee!'" Isaac laughs so hard he gives a little snort. "Yeah," he says, composing himself again, "we didn't win." But something stuck and Isaac ended up being in a series of ska-punk outfits, first Paperface, then The Worms and later The Blinking Underdogs who, legend has it, would go on to support Green Day. "Supported… Ha! It was a festival…" says Isaac. "But hey, we played the same day, at the same festival, within a few hours of each other." (On YouTube you can find a clip from 2001 of The Blinking Underdogs performing in a battle of the bands contest at somewhere called Spanky's. Isaac is wearing a 'New York City' T-shirt and brandishing a wine-coloured Flying V electric guitar.)

Still, Isaac's path was uncertain. At one point he thought about joining the Marines. "The sax player in my band had grown up in a military family so we were like, 'Hey, let's work out and get all ripped and be badasses!'" he says. "I was like, 'Yeah, I'll do combat photography!' My dad was really against it. He said, 'Clinton's just going to make up a war for you guys to go to,' so I had to have the recruiters come all the way down to Miami where my dad was living and they convinced him to let me join. I did the exam, I took the oath, but then we had gotten the money together to record an album with The Worms. I decided I'd join the Reserves instead. I said I wanted to do combat photography. They said, 'We don't do that in the Reserves, but we can give you anti-tank?' Ha! I was like, 'it's a liiiiiittle different to what I was thinking…'"

Even when he started doing a few professional theatre gigs in Miami he was still toying with the idea of a music career, until one day, while in New York playing a young Fidel Castro in an off-Broadway production of Rogelio Martinez's play, When it's Cocktail Time in Cuba, he happened to pass by renowned performing arts school Juilliard. On a whim, he asked for an audition. He was told the deadline had passed. He insisted. They gave him a form. He filled it in and brought it back the next day. They post-dated it. He got in. And the rest is history. Only it wasn't.

"In the second year they would do cuts," Isaac says. "If you don't do better they kick you out. All the acting teachers wanted me on probation, because they didn't think I was trying hard enough." Not for the first or last time, he held his ground. "It was just to spur me to do better I think, but I definitely argued."

He stayed for the full course at Juilliard, though it was a challenge, not only because he'd relaxed his own non-drinking rule but also because he was maintaining a long-distance relationship with a girlfriend back in Florida. "For me, the twenties were the more difficult part of life. Four years is just… masochistic. We were a particularly close group but still, it's really intense." (Among his fellow students at the time were the actress Jessica Chastain, with whom he starred in the 2014 mob drama A Most Violent Year, and Sam Gold, his director in Hamlet.) He says he broadly kept it together: "I was never a mess, I just had a lot of confusion." He got himself an agent in the graduation scrum, and soon started picking up work: a Law & Order here, a Shakespeare in the Park there; even, in 2006, a biblical story to rival his early efforts, playing Joseph in The Nativity Story (the first film to hold its premiere at the Vatican, no less).

By the time he enrolled at Juilliard he had already dropped "Hernández" and started going by Oscar Isaac, his two first given names. And for good reason. "When I was in Miami, there were a couple of other Oscar Hernándezes I would see at auditions. All [casting directors] would see me for was 'the gangster' or whatever, so I was like, 'Well, let me see if this helps.' I remember there was a casting director down there because [Men in Black director] Barry Sonnenfeld was doing a movie; she said, 'Let's bring in this Oscar Isaac,' and he was like, 'No no no! I just want Cubans!' I saw Barry Sonnenfeld a couple of years ago and I told him that story — 'I don't want a Jew, I want a Cuban!'"

Perhaps it's a sad indictment of the entertainment industry that a Latino actor can't expect a fair run at parts without erasing some of the ethnic signifiers in his own name, but on a personal basis at least, Isaac's diverse role roster speaks to the canniness of his decision. He has played an English king in Ridley Scott's Robin Hood (2010), a Russian security guard in Madonna's Edward-and-Mrs-Simpson drama W.E. (2011), an Armenian medical student in Terry George's The Promise (2017) and — yes, Barry — a small, dark American Jew channelling a large blond Swede.

But then, of course, there are roles he's played where ethnicity was all but irrelevant and talent was everything. Carey Mulligan's ex-con husband Standard in Nicolas Winding Refn's Drive in 2011 (another contender for his "spectacular deaths" series); mysterious technocrat Nathan Bateman in the beautifully poised sci-fi Ex Machina (2014) written and directed by Alex Garland (with whom he has also shot Annihilation — dashing between different sound stages at Pinewood while shooting The Last Jedi — which is due out next year). Or this month's Suburbicon, a neat black comedy directed by George Clooney from an ancient Coen brothers script, in which Isaac cameos as a claims investigator looking into some dodgy paperwork filed by Julianne Moore and Matt Damon, and lights up every one of his brief scenes.

Isaac is a very modern kind of actor: one who shows range and versatility without being bland; who is handsome with his dark, intense eyes, heavy brows and thick curls, but not so freakishly handsome that it is distracting; who shows a casual disregard for the significance of celebrity and keeps his family, including his father, who remarried and had another son and daughter, close. It's a testament to his skill that when he takes on a character, be it English royal or Greenwich Village pauper, it feels like — with the possible exception of Ray LaMontagne — it could never have been anyone else.

Today, though, he's a Danish prince. To say that Isaac's turn in Hamlet has caused a frenzy in New York would be something of an understatement. Certainly, it's a sell-out. The Sunday before we meet, Al Pacino had been in. So scarce are tickets that Isaac's own publicist says she's unlikely to be able to get me one, and as soon as our interview is over I hightail it to the Public Theater to queue up to be put on the waiting list for returns for tonight's performance. (I am seventh in line, and in my shameless desperation I tell the woman in front of me that I've flown over from London just to interview Isaac in the hope that she might let me jump the queue. She ponders it for a nanosecond, before another woman behind me starts talking about how her day job involves painting pictures of chimpanzees, and I lose the crowd.)

Clearly, Hamlet is occupying a great deal of Isaac's available brain space right now, and not just the fact that he's had to memorise approximately 1,500 lines. "Even tonight it's different, what the play means to me," he says. "It's almost like a religious text, because it has the ambiguity of the Bible where you can look at one line and it can mean so many different things depending on how you meditate on it. Even when I have a night where I feel not particularly connected emotionally, it can still teach me. I'll say a line and I'll say, 'Ah, that's good advice, Shakespeare, thank you.'"

Hamlet resonates with Isaac for reasons that he would never have foreseen or have wished for. While playing a young man mourning the untimely death of his father, Isaac was himself a young man mourning the untimely death of his mother, who died in February after an illness. Doing the play became a way to process his loss.

"It's almost like this is the only framework where you can give expression to such intense emotions. Otherwise anywhere else is pretty inappropriate, unless you're just in a room screaming to yourself," he says. "This play is a beautiful morality tale about how to get through grief; to experience it every night for the last four months has definitely been cathartic but also educational; it has given structure to something that felt so overwhelming."

In March, a month after Eugenia died, Isaac and Lind married, and then in April Eugene, named in remembrance of his late grandmother, was born. I ask Isaac about the shift in perspective that happens when you become a parent; whether he felt his own focus switch from being a son to being a father.

"It happened in a very dramatic way," he says. "In a matter of three months my mother passed and my son was born, so that transition was very alive, to the point where I was telling my mom, 'I think you're going to see him on the way out, tell him to listen to me as much as he can…'" He gives another laugh, but flat this time. "It was really tough because for me she was the only true example of unconditional love. It's painful to know that that won't exist for me anymore, other than me giving it to him. So now this isn't happening" — he raises his arms towards the ceiling, gesturing a flow coming down towards him — "but now it goes this way" — he brings his arms down, making the same gesture, but flowing from him to the floor.

Does performing Hamlet, however pertinent its themes, ever feel like a way of refracting his own experiences, rather than feeling them in their rawest form?

"Yeah it is," he says, "I'm sure when it's over I don't know how those things will live." He pauses. "I'm a little bit… I don't know if 'concerned' is the right word, but as there's only two weeks left of doing it, I'm curious to see what's on the other end, when there's no place to put it all."

It's a thoughtful, honest answer; one that doesn't shy away from the emotional complexities of what he's experiencing and is still to face, but admits to his own ignorance of what comes next. Because, although Isaac is clearly dedicated to his current lot, he has also suffered enough slings and arrows to know where self-determination has its limits.

What he does know is happening on the other end of Hamlet is "disconnection", also known as a holiday, and he plans to travel with Lind to Maine where her documentary, Bobbi Jene, is screening at a film festival. Then he will fly to Buenos Aires for a couple of months filming Operation Finale, a drama about the 1960 Israeli capture of Adolf Eichmann which Isaac is producing and in which he also stars as Mossad agent Peter Malkin, with Eichmann played by Sir Ben Kingsley. At some point after that he will get sucked into the vortex of promotion for Star Wars: The Last Jedi, of which today's interview is an early glimmer.

But before that, he will unlock the immaculate black bicycle that he had chained up outside the hotel and disappear back into Brooklyn. Later, he will take the subway to Manhattan an hour-and-a-half or so before curtain. To get himself ready, and if the mood takes him, he will listen to Venezuelan musician Arca's self-titled album or Sufjan Stevens' Carrie and Lowell, light a candle, and look at a picture of his mother that he keeps in his dressing room.

Then, just before seven o'clock, he will make his way to the stage where, for the next four hours, he will make the packed house believe he is thinking Hamlet's thoughts for the very first time, and strut around in his underpants feigning madness, and — for reasons that make a lot more sense if you're there which, thanks to a last-minute phone-call from the office of someone whose name I never did catch, I was — stab a lasagna. And then at the end of Act V, when Hamlet lies dead, and as lightning staggers across the night sky outside the theatre, finally bringing the promised drama to the Manhattan skyline, the audience, as one, will rise.

Fashion by Allan Kennedy. Star Wars: The Last Jedi is out on 15 December. The December issue of Esquire is out now.

Miranda Collinge is the Deputy Editor of Esquire, overseeing editorial commissioning for the brand. With a background in arts and entertainment journalism, she also writes widely herself, on topics ranging from Instagram fish to psychedelic supper clubs, and has written numerous cover profiles for the magazine including Cillian Murphy, Rami Malek and Tom Hardy.