Imagine meeting the guy who invented the mosquito. Or the woman who came up with the idea for the cold sore. Well, I am huddled in a black cab, our knees clunking together as we careen round corners, with the two men who introduced the no-booking policy to central London's restaurants.

Instinctively, you might not think that waiting in line for 40 minutes or so for someone to serve you some delicious food has very much in common with malaria or with

herpes. But you would be wrong. It's maddening and it's unnecessary and anyone who really enjoys eating well will have found their lives blighted by it these past few years. "A total pain in the arse" is how critic Jay Rayner described the no-reservations trend. Esquire editor-at-large Giles Coren has repeatedly gone full Coren on it, writing that it only works for "twentysomething hipsters who go out in the evening mostly to get drunk and have sex and for whom the off-chance of being served a cheeseburger after a two-hour wait is a good enough reason to select a dinner destination". OK, it's democratic, we get it, but then so was the decision to leave the European Union.

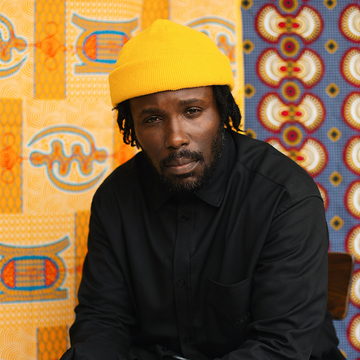

So, Sam and Eddie Hart, the urbane, relentlessly cheery proprietors behind three Barrafina tapas restaurants, all within seven minutes' walk of each other in Soho and Covent Garden, defend yourselves.

"Yes, we were the first ones to do it, I'm afraid," sighs the older brother Sam, 42. "But I actually believe the customer can and does benefit in many ways from no bookings."

Barrafina on Frith Street has a legitimate claim for being the most influential restaurant to open in the United Kingdom this century. It arrived in 2007, just prior to the financial crisis, in a long, thin site on Soho's least interesting street. It had a head chef that no one had heard of: a young Basque woman called Nieves Barragán Mohacho, whom the Harts brought across from their first venture, Fino in Fitzrovia. Barrafina served Spanish food that few people in Britain had eaten before: empanadas, para picar and torrijas, along with an uncompromising Iberian wine and sherry list. All dishes were designed to be shared.

Then there was the problematic space it occupied. The main room was so tight the brothers calculated they could only fit 23 diners, sitting along an L-shaped marble bar on burgundy leather stools, at any one time. The cooking would take place inches from the customers' faces: at its best, it would be engrossing live theatre; but if anything went wrong it would be messy and acutely embarrassing. To make any dent on the steep rent they were paying, Barrafina would have to constantly "turn tables" — as soon as one

group finished eating they would be replaced by another. Hence no bookings, so there was no time lag and no no-shows. The Harts were so committed to the idea that the restaurant didn't even have a telephone.

Turning tables is a controversial concept in the hospitality trade: no diner wants to feel their waiter is desperate for them to chug their coffee and get out. The Harts, however, wanted to improve and streamline the operation at Barrafina. Although there were only 23 customers, they would be attended by six chefs and four waiters. This is a ratio you might expect to find in the world's most exclusive, Michelin-starred restaurants, where you could expect to pay £150 per head. In Barrafina, the average spend would be nearer £40–45 each.

"So you're getting all that service, all those people dedicated to you when you're there, which we can do financially because of the no reservations," explains Sam Hart as we zip across Blackfriars Bridge. "We're forcing people to come early, we're forcing them to come late and making sure we've got the turns. So although it's very inconvenient if you want to turn up and have four people at 8 o'clock, what we can produce for the price is much higher than if we just had one sitting and everyone comes at once."

The Harts knew they were limiting their appeal: Barrafina is a disastrous place for

a business meeting, for Granny Elsie's 80th or for any time where there are more than three of you eating, really. "Oh, it was a massive gamble," says Sam. "We were really nervous, because no one had really done that in London for that sort of restaurant before. We had no idea how it was going to work."

Almost a decade on, Barrafina has exploded the London restaurant scene. The Frith Street branch won a Michelin star, a shock turn-up for such an informal dining spot. Its second outpost, on Adelaide Street, Covent Garden, which has 29 stools, was named best restaurant at the 2015 National Restaurant Awards. Successful restaurants might turn tables twice, maybe three times at a push, in a session; Barrafina on Frith Street will typically do it eight times a day. "Which is ridiculous," acknowledges Sam. Inevitably, others followed in their path by eschewing bookings: notably the Polpo chain — run by Esquire's man with a pan Russell Norman, a long-standing admirer of Barrafina — and the stylised Bombay cafés Dishoom.

The kerfuffle over reservations, though, almost obscures the really radical change in eating out that the Harts have contributed to. When the recession bit, one of the main casualties was the refined, stately restaurant. People still wanted to eat well, but there was little appetite any more for white tablecloths and obsequious waiters. Barrafina has come to epitomise how we want to dine out now: excellent food, attentive but informal service in a place that, because it's invariably full, has an atmosphere. Small, shared plates are almost a cliché now, as are open kitchens. Soho, for so long a food desert, has in recent times become the most exciting gastronomic square mile in the country. The Harts can take a chunk of credit for that, too.

The cab pulls up outside a shuttered railway arch on the edge of Borough Market in south London. We're here to look at the Hart brothers' new restaurant site: where they hope the food world will be clamouring to go next. The building used to be an oyster shack called Shuck, but the previous owners could never make the narrow entrance and cavernous interior work. Sam Hart pays the driver: "And yes, sorry, this one is going to be no

reservations, too."

The story of the latest Hart brothers venture, El Pastor, goes a long way back, to Mexico City in the mid-late Nineties. Sam Hart, to this point, had lived a pretty sheltered existence. The brothers have called themselves "bumpkins" who "grew up in the middle of nowhere". Their father, Tim, was an investment banker at Lehman Brothers; Stefa, their half-Scottish, half-Bulgarian mother, was an interior designer. They own Hambleton Hall, an exclusive country-house hotel in Rutland that has protected its Michelin star for more than three decades. Sam went to school at Eton, then on to Manchester University to read economics. After graduating, he got a job at a foreign exchange brokerage and, aged 22, he volunteered to go out to a new office it was opening in

Mexico City.

So far, so Bullingdon Club. But Sam Hart — and Eddie, too — is not the stuffed-shirt, lookatmyfuckingredtrousers clone that you might take him for at a cursory glance. Within six months in Latin America, he'd quit the job at the brokerage, disillusioned that his Mexican boss was embezzling money — "I was a central-office spy, so more or less consigned to the stationery cupboard" — and decided to open a jazz and underground house nightclub. It was called El Colmillo (The Fang) and could be found in a colonial house in the Juárez district. Cool Britannia was in full swing and Hart brought over one of the star bartenders from Oliver Peyton's Atlantic Bar and Grill for three months to teach his team to make cocktails. Absolut was the hot spirit back then and El Colmillo became its first flagship Latin American bar.

"It tended to be the slightly hipper, moneyed Mexicans that would come," Sam says. "Quite a lot of the TV, music and media lot, some of the cooler, well-travelled Mexican kids. So we'd have the president's son one day but we'd also have American A-list movie stars another day. You could say that anyone who was anyone in Mexico at that period did come. We had 500 people a night for 10 years, so that's a lot of people and, on

a good night, they'd all be in."

Hart's partner in El Colmillo was Crispin Somerville, a friend from Manchester University. Somerville's background was as eclectic as Hart's was conventional: he had a bit-part in Chris Morris' The Day Today in the yoof spoof Sorted with Graham Linehan and had been a shambolic VJ on MTV (think: rocking up to interview Ash while seeming to have little idea who they are). He arrived in Mexico on the way to Colombia to write a book about professional hitmen, but when El Colmillo started up, he found himself staying for a decade. He would subsequently go on to manage Lily Allen's record label, launch a book publishing house and become a registered naturopath, specialising in iridology, a technique that believes you can diagnose a person's ills through looking into their eyes. Standing outside the site of El Pastor in Borough Market, I tell Somerville — who has met us along with a new Hart brother, 34-year-old James, who has recently joined the family business after a decade as a derivatives broker in the City — that he's packed a respectable amount into 44 years and he wrinkles his nose and replies, "Yeah, it is quite a disparate CV."

Life in Mexico was rarely straightforward. The country typically features in the top three most corrupt places to do business on the planet. It was never easy telling the president's son that he couldn't bring guns into the club. Most of the team were robbed at some point. But it was fun. "As a 22-year-old, we really enjoyed the lawlessness of it," Sam Hart recalls. "If you did something wrong, drink driving or something, a policeman pulls you over and you pay him $20 and go on your way. So, a real feeling that you could just do what you wanted."

In their downtime from the club, Hart and Somerville became obsessed with a local speciality called tacos al pastor. It is thought to have arrived in Mexico in the Fifties and Sixties, along with a wave of Lebanese immigrants fleeing their homeland after the 1948 Israel-Lebanon war and the Six Day War of 1967. In many respects it is a tweak on the classic lamb shawarma, but instead of spit-grilled lamb, the meat is pork, which has been marinated in chillies, spices and is often topped with pineapple. It is carved from an upright grill, served on a fresh corn tortilla with salsa and a drizzle of lime juice. There are stands pretty much every 50m in Mexico City, but Hart and Somerville would cross the city trying to find the perfect pastor.

"We spent collectively 15 years of research — five years for Sam, 10 years for me — really going across a city of 21m people in a search for the best pastor," says Somerville. "They can vary wildly and one of our culinary pleasures was going to weird places because we'd heard it had a great pastor. When you really get into creating a very good pastor, it's very complex. It is not a coincidence that this dish is not on the menu of any Mexican restaurants in this country. Because, until you've got the baseline, tacos al pastor is a really expensive, really work-intensive, laborious dish to create."

The Hart brothers want to do this right: El Pastor will make its own corn tortillas on site, the only restaurant in London to do so; the pork will be shoulder and belly, marinated overnight in achiote and vinegar to tenderise it. Chefs from Mexico will come to supervise production in the early days, and cooks from Britain will gain experience over in Mexico. The place will just serve tacos al pastor, with maybe a couple of specials, and it will be cheaper than Barrafina, at around £20 a head, depending on how hard you decide to hit the mezcal. "Simple things are often deceptively difficult to do," Sam Hart says. "But the pastor is, in my opinion, Mexico City's greatest dish by

a country mile. The gamble is: can we do it to a level that we're hoping to?"

"Can I talk about the first vom of the season?" asks Crispin Somerville, over lunch at Barrafina in Drury Lane, Covent Garden.

Eddie Hart, who is 39, giggles his assent. "So Eddie, the other day, was telling me about how traditionally there's always the puking season, which begins in late November and runs through till just before Christmas," Somerville goes on. "And Eddie is known across the group to get his Marigolds on and clean up the first puke of the puking season. Now, this is quite a roundabout way of explaining it, but what this means is that the staff are looking at the owners and going, 'This is a unique scenario,' because that doesn't happen across other restaurants they've worked in. That's something that becomes infectious to the diner but a lot further down the line."

At the heart of the Harts' offering, at all their restaurants, is a kind of unfussy-yet-rigorous service. They seem reluctant to talk about this aspect themselves — perhaps modesty prevents them — but the stories spool out as soon as you ask anyone who knows the brothers to explain their success. Another legend is how particular Eddie is about the way that coffee and tea should be served. Even regulars at Barrafina and Quo Vadis, the 90-year-old Soho grande dame the Harts have owned since 2007, have probably never noticed it, but when the waiter serves it, the handle of the cup is just slightly angled so that it is in exactly the right place when your hand drops. The teaspoon sits on the saucer again in the most intuitive spot.

James Hart, who is smiley and charming, an apple not fallen far from the tree, clearly views his brother's behaviour as lying somewhere between eccentricity and OCD. "I was going to see Eddie once when he was working and I noticed he'd put the coffee cup the wrong way round, with the spoon on the other side," he says. "So I thought obviously he'd completely lost his marbles and fucked it up. And I pointed it out to him in a rather younger-brotherish type way and he said, 'No, no, no, I just noticed he's left-handed.' At which point I thought, 'Hang on a second, I've got quite a lot to learn about this.'"

The root of this attentiveness appears to be hereditary. By all accounts their father was a hard task-master who made his three sons work in their holidays, and not a "do

a couple of hours on reception before I make you the manager" nepotism, either. While Sam went to Mexico City, Eddie stayed home and did a series of jobs around Hambleton Hall, at Hart's, the family's boutique hotel in Nottingham, and at its events company for five years.

"I pretty much worked my way through every department, from barman to housekeeper to chambermaid to receptionist," says Eddie Hart. "And I loved his business. Loved the business. My success at school was mixed, so actually to leave school at the age of 18 and embark on something where

I felt useful and I was really passionate about what I was doing was a huge relief."

From their mother, who was raised in Mallorca, came the obsession with Spanish food. Every summer, the family went to their house in Estellencs, a village on the northwest coast of the island. They grew up eating red peppers and aubergines, which might not seem too unusual now but was wildly exotic for Seventies Rutland. This style of cooking was the backbone of the first restaurant the Harts opened, Fino, in 2003, and has subsequently been integral to Barrafina, too.

Eddie Hart, especially, is a master at making sure a restaurant service runs smoothly. He's often to be found at the door greeting diners — at Barrafina and Quo Vadis, there always seems to be a Hart on site, which is the beauty of having two, and now three, brothers — or flitting between tables to ensure standards are being maintained.

"They won't really talk about that, because it's so in the blood," says Somerville. "Hambleton is one of the most service-centric places in the country and none of them have picked up on the fact it was drilled into you because you came from that world. I'm really interested in the Malcolm Gladwell 10,000-hours thing [the theory this is how long it takes to achieve excellence in a field] and it's like they'd done their 10,000 hours before many had got off the starting blocks."

It can be hard sometimes to know where one Hart brother begins and another one stops. Sam is perhaps a fraction taller, and Eddie has floppy hair and sparkling blue eyes, but intentionally or not, they often dress almost identically. The effect is a little Gilbert and George. Today, they are both in white shirts — Sam's crisp, Eddie's linen — blue jeans and loafers. For two decades they have had their suits made by an eccentric Jamaican tailor called Sherlock Hart (no relation) who has a small shop on Kingly Street in Soho. Sherlock Hart seemed to be nearing retirement age when they met him, but he continues to cut and stitch, apparently ageless. Eddie favours fogeyish, military-

cut trousers with a very high waist, just like his father.

"They are almost like twins," says Jeremy Lee, the head chef at Quo Vadis and their partner in the business. "That's why you do talk about them in the same sentence because they just think as one. They can look up and know instantly what the other is thinking and that's quite something."

If forced to separate them, you might think Sam was the more sober, grown-up of the pair. He lives in Acton, west London, with his wife and three children; Eddie, meanwhile, is single and has a houseboat parked underneath Battersea railway bridge. There's a barge that delivers kegs of beer and, on a clement summer's afternoon, he'll toddle down the Thames to eat at The River Cafe. You'd imagine that Sam, with his background in economics and the City, would concentrate on the financial side of the operation, while Eddie, who studied interior design for a year at the Inchbald School of Design in London, would oversee the layouts and details of the restaurants. But that doesn't seem to be the case. They take decisions collectively and rarely disagree.

"There were a couple of years when we used to beat each other up," says Sam, "but by about the age of eight and 10 that was behind us and then we were best buddies ever since, I suppose."

Sam Hart, especially, is easy to misread on a first meeting. He is polished, charming, clearly highly competent, completely at ease in Soho, but it is difficult to imagine him thriving in lawless Mexico City. Yet, over time, he proves to be full of surprises. He's obsessed with music, especially old-school hip-hop (the week before we meet he took his 13-year-old son to his first gig: Cypress Hill at Brixton Academy). "I've really learned not to judge books by their covers," says Somerville. "There's definitely a glint in all three of the brothers' eyes. They are very good at enjoying themselves and actually they are all quite surreal. You look at them at first and think they are going to be quite strait-laced. But some of the things that come out of their mouths are both extraordinarily compassionate and then insanely funny.

"That's the kind of person I want to be hanging out with," Somerville continues. "They have an unexpected, broad, inclusive and non-judgemental way of looking at the world. And that goes right through the teams who work with and under them."

Even people who detest the no-reservations culture find it hard to dislike the Harts personally. If anything, they seem too nice, suspiciously affable and unfailingly genial. Can you really become so successful in the restaurant world without ruffling any feathers? Well, there is clearly a steel to the brothers. When Fino, their baby, stopped performing — certainly compared to Barrafina, anyway — they wasted little time in closing it down last year. The decision was made easier by the fact that they could transfer the staff, almost to a man and woman, to a new, third Barrafina.

"If you are having to pay every month to keep somewhere open, that does tend to dampen your love for it," reasons Sam Hart. "So, just from a practical perspective we

were not making any money, but more importantly than that, it felt that it was becoming not exactly irrelevant but it had become a little bit dated. There were lots of

other tapas places around that were less

formal and a bit more fun."

There is a sense that now is a key strategic moment for the Harts. In September, they re-open Quo Vadis, after a dramatic six-week overhaul. Occupying three Grade I-listed and one Grade II-listed townhouses, it is perhaps the grandest, most unwieldy money pit in Soho. Karl Marx lived there with his family in the 1850s, but it has been a restaurant since 1926, most notoriously when Damien Hirst and Marco Pierre White owned it from 1996 to 2007. The Harts admit that they have never made a penny during their nine years in charge, but this renovation plans to change that. On the ground floor, Barrafina, which has recently been evicted from its Frith Street home, will cosy up with a more intimate Quo Vadis. Upstairs, always one of London's louchest after-hours members' clubs will be reimagined as one of London's louchest after-hours members' clubs where the members actually pay their fees.

Then, in October, El Pastor arrives, with James Hart at the helm, Sam and Eddie looking over his shoulder. And if you want proof that Sam and Eddie Hart can be hard-nosed, they only agreed to bring their little brother into the company when they were sure he could add value to the operation. You don't give away equity for nothing. When

I ask Crispin Somerville what his role is, he replies, "In terms of El Pastor, I can only describe myself as Bez, really."

The Harts hope and believe they are on to something with their Lebanese-Mexican wraps. Their instinct is that Mexican food in the UK is about where Spanish cuisine was in 2007 when they opened Barrafina: ready to tip. The restaurant's location, on the edge of London's most famous food market, feels right. But until people come, and come again, and tell their friends, and stand in line for an hour to get served, they won't know if they are right. One thing they don't worry about is the pastor itself. Sam Hart smiles, "If we can produce what we are planning to produce, we're not worried that people won't like it. It's one of the most delicious things you'll ever eat."