Hunched nude in the glow of his iMac, 17-year-old Darren* typed the words 'gay porn' into Google for the first time.

"I didn't fancy men," he tells me. "I had a girlfriend, and only ever had sexual feelings for women, but I just couldn't shake the idea that I was somehow lying to myself."

He plugged in his headphones, clicked on an X-rated video and took a deep breath. It was around 3am, in the summer of 2007, and relentless fears of homosexuality had tormented him since the start of the year. "I just woke up one day and I was suddenly obsessed with it. It felt like everything I thought I knew about myself was falling apart. It didn't make any sense."

He watched, expecting something significant to stir upstairs or down. But there was nothing. Feeling equal measure victory and defeat, Darren switched off the monitor, laid flat on his bed and wrestled with his doubts for a few more hours before finally surrendering to sleep. He carried out the same test almost every night for the next three weeks, always with the same result.

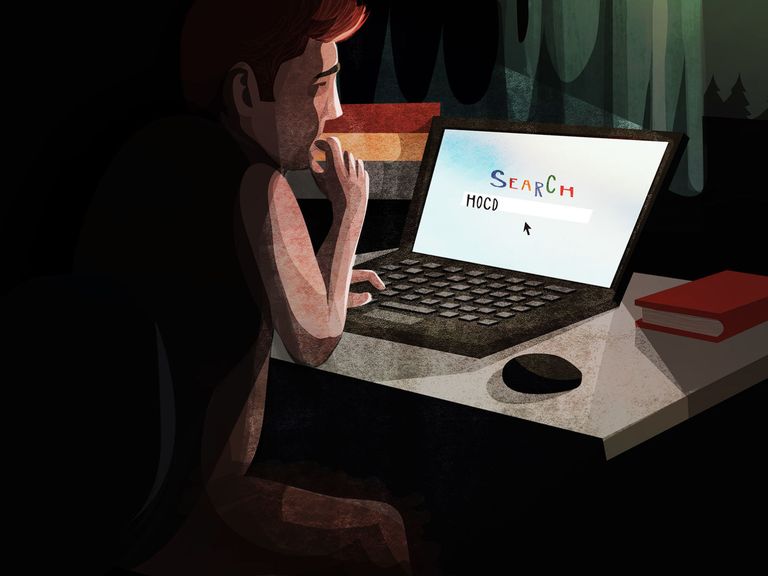

After searching Internet mental health forums for answers to his private impasse, Darren became convinced that he was suffering from 'HOCD': a not officially recognised form of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder defined by the fear of being or becoming homosexual.

A decade has passed since Darren's self-diagnosis and subsequent therapy, but 'HOCD' still remains a divisive subject within some sections of the psychological healthcare community. Now 26, he is keen to raise awareness for what he believes to be a misunderstood and potentially life-ruining anxiety disorder.

"I was fobbed off by therapists who just thought that I must be gay. I don't want that happening to anybody else."

Avy Joseph is an accredited Cognitive Behavioural Therapist and lecturer with 25 years experience treating anxiety disorders. While he asserts that 'HOCD', an acronym coined by sufferers sharing their stories online, isn't officially classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), he says that the irrational fear of being or becoming gay falls firmly within the umbrella of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.

"Someone will tell me that they were walking down the street and saw a guy, and thought: 'Oh, he's really good looking.' But then they think: 'oh my God, I've just noticed a guy and thought he was good looking. Does that mean…'"

According to Joseph, it's at such innocuous beginnings that a self-perpetuating and all-consuming obsession with sexual identity can begin. "The more you insist that you mustn't have a particular thought, guess what happens? You're going to have hundreds of them," he tells me. "That causes anxiety, and then you start to think more unrealistically. The ability to think in a probabilistic way goes out the window. Then you ask yourself: 'How can I be absolutely sure that these thoughts won't come back?' And then of course you start demanding certainty…"

A commonly held misconception about OCD is that sufferers are all fixated with decontamination and uniformity. The truth is, for many, OCD has nothing to do with overworked light switches or compulsive hand scrubbing, and all to do with intrusive, relentless, and often distressing thoughts that swarm around their heads on a daily basis.

Little research has been published on the rates of sexual obsession in OCD sufferers, but a recent study using a sample of 293 subjects found that 25% experienced intrusive sexual thoughts. And while analysis is scarce, a Google search reveals a seemingly endless scroll of people sharing their 'HOCD' experiences on forums, and YouTube videos on the topic often wrack up tens of thousands of views.

Aaron Harvey, founder of non-profit OCD awareness project intrusivethoughts.org, is a former sufferer who found fraternity on the internet. "[There was] solace in the stories of teens on YouTube, and hope from older generations sharing experiences and treatment recommendations. If it were not for this community, I may not have made it," he tells me.

From the age of 11, Aaron was plagued by sexually intrusive thoughts, culminating in suicide ideations at the age of 21. For him, it was a full-time affliction. "Sufferers will spend hours per day 'checking' or 'testing' themselves to try to get to the 'truth' about their sexual identity. I would constantly check levels of arousal. Objectively assess my instinctive attraction towards females and my lack of interest in the male form. I even had obsessions that I was actually in love with my former partner's brother."

According to Aaron, four out of five people get intrusive thoughts, but one in fifty find them much harder to dismiss, quickly developing into an all-consuming obsession.

He says these intrusive thoughts can often lead sufferers to make drastic life decisions. "They may go as far as to plan coming out to family and friends, all the while not believing they are gay. In relationships they may withdraw from their partners emotionally and physically, because when you fear that you don't know who you are, you become paranoid you may be selling a lie to the person you love the most."

But what causes someone to fear the prospect of being gay in the first place? Darren says he grew up in a "liberal-ish" household and believes that homosexuality would have been accepted by his family and friends, but it's easy to see how a less tolerant upbringing could turn homosexuality into a cause for anxiety. Aaron, for example, grew up in a religious home in Orlando, Florida, and attended a private Christian school: "Trying to run from [what he'd been told were] violent, blasphemous and devious thoughts was extremely painful. I had no sense of identity. I had no idea who I was."

Rose Bretécher, bestselling author of OCD memoir Pure O, also experienced intrusive doubts about homosexuality, constantly fearing that her life as a straight woman was a lie. "OCD is sometimes called the 'doubting disease', because sufferers struggle with this kind of uncertainty," she says. "The more I soul-searched, the worse the doubts and accompanying sexual mental images got. My sense of self was slipping away, causing chaos, anxiety and depression." She had no way of distinguishing whether the thoughts she was experiencing were merely intrusive or true reflections of her sexuality.

Nowadays, the majority of established OCD charities – including OCDUK, OCDAction and Mind - address intrusive sexual thoughts as a common trope of the disorder, but that has done little to stem a backlash from some high-profile skeptics within the psychological community, who believe that HOCD is at best misguided, and at worst homophobia in its most pernicious guise.

In November 2015, BuzzFeed UK's LGBT editor Patrick Strudwick published an article titled '"World's Leading Anxiety Expert" Offers Treatment For People Who Worry That They're Gay' that heavily criticised the practice of a Harley Street therapist named Charles Linden who, according to the site, boasted of a "100% success rate" in the treatment of "HOCD".

At the time the article was written, Linden's publishers were dubbing him as "the world's leading authority on anxiety", and his website made hefty promises to sexually-confused OCD sufferers. "If you are experiencing HOCD … and the thoughts it causes," the site read, "you are not gay and when you do my Method to eliminate this and your other anxieties you'll find out why you think you might be and why you certainly are NOT!"

In their report, BuzzFeed revealed that Linden lacked any medical, psychiatric or psychotherapeutic training, ultimately managing to get his practice disavowed by two major mental health organisations that had previously featured as endorsements. He has since introduced a number of caveats on his website, and remains as Google's featured result for the search 'HOCD'.

BuzzFeed's skepticism wasn't aimed solely at Linden's shaky credentials and clumsy phrasing but also towards the credibility of sexuality-centred OCDs as a whole, and the ethics of therapists who seek to treat it. They interviewed a number of prominent mental health professionals on the matter, who echoed the argument that the concept of 'HOCD' was seeped in homophobia and pseudo psychology.

Elizabeth Peel, chair of the British Psychological Society's 'Psychology of Sexualities' section and a professor of Communication & Social Interaction at Loughborough University, states within the piece that: "The term 'Homosexual OCD' is simply conversion therapy under another guise and something we strongly condemn as damaging."

She went on to say: "People should be wary of the way this therapy is being promoted, and there are no published peer-reviewed studies to back up the claims that are being made."

Professor Dinesh Bhuga, a former president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, also criticised the practice, telling BuzzFeed: "HOCD is not a recognised condition. By 'creating' such a condition there is a serious danger of medicalising normal human emotions and turning lots of people who are in various stages of coming out, and for various reasons are struggling to accept their sexuality, into 'ill' individuals."

It's clear that the term 'HOCD', coined by online sufferers and unrecognised by the DSM (which only references obsessions with "sexual imagery"), can act as a muddying misnomer in the conversation around intrusive sexual thoughts. Even Bretécher believes the phrase is a "little misleading", and the organisation OCDUK has warned that such unendorsed acronyms provide unnecessary confusion to sufferers and mental health professionals alike.

And yet despite these condemnations, the treatment of intrusive sexual thoughts has across-the-board recognition within the OCD community. Is it just a matter of semantics? Or does it point to a deeper disagreement?

I asked Elizabeth Peel to clarify her "conversion therapy" comments. In response she wrote: "The point I was making was that 'Homosexual OCD', as I understand it, is very similar to 'internalised homophobia'. The main issue is not to treat same-sex sexuality as something that is problematic."

Aaron believes this is a misinterpretation of the problem at hand. "The statement that 'HOCD is conversion therapy under another guise' breaks my heart," he tells me over email. "It demonstrates the pomp of academia and the fundamental divide between their community and ours. Misinformation is everywhere. And it's not just in message forums, it's coming from the mouths of therapists, religious counselors, psychologists and psychiatrists who fundamentally do not understand OCD. Thus, the explosion of online communities."

When Darren suffered a "kind of breakdown" in 2007, he looked to the NHS for help. "The thoughts were getting impossible to live with, so I drove to the hospital and they sat me down with what I think was a psychologist. I opened up about how I was feeling, but he looked bored and said: "Well, maybe you're just gay" and handed me a leaflet. That set me back a long way."

Peel's reference to gay conversion therapy - the wholly discredited and dangerous effort to 'cure' homosexuality - certainly darkens the tone of the conversation. And in an age where even the Vice President of the United States has expressed tacit support for the practice, it's understandable that high profile figures in the psychological community would condemn anything that could fuel the rhetoric of homophobic 'therapists', or provide party-line approval of their methods. After all, despite recent headways by LGBT groups and denunciation from former President Barrack Obama, gay conversion therapy is still legal across the US and only six states have banned the practice in relation to minors. It's clear that, in America at least, the fight is far from over.

But could it be that this kind of socio-politically vigilant thinking might impede our ability to engage with this particular mental health disorder in a nuanced manner? While attempts to dismiss the condition may be well-intentioned, they risk leaving sufferers without proper psychiatric help.

"As a gay man, I'm certainly not interested in converting gay men into straight men. Sexuality is organic as far as I'm concerned," Avy Joseph says when I bring up the subject of conversion therapy.

"If a client who is gay but anxious about the consequences of accepting themselves or coming out goes to a therapist who has an agenda about homosexuality, then of course that therapist isn't working in the best interest of their clients. I imagine they exist, but I've never met one who would publicly say homosexuality is wrong. It's completely unethical."

Rose Bretécher believes the accusation HOCD is just 'internalised homophobia' is incorrect, but doesn't blame anyone for leaping to such a conclusion: "People's understanding is only as good as the information available out there – and awareness is still pretty poor. I think curious skepticism is healthy and that personal testimony alone doesn't prove much. But thankfully no-one has to take my word for it – go read the huge amount of objective information available on specialist OCD web-sites and charities."

Joseph tells me that he has never had a gay person come to him with intrusive thoughts about heterosexuality, but testimony exists on Internet forums, and the OCD Center of Los Angeles states that it does happen. "Over the years, therapists here […] have treated many homosexuals (male and female) who are plagued by obsessive fears of being "straight", and who suffer equally when OCD attacks their sexual identity," states their website, which also offers an online HOCD test. "It is not exclusive to heterosexuals. At its core, sexual orientation OCD is the fear of not knowing for sure, paired with the fear of never being able to have a healthy, loving relationship with a partner to whom one feels genuinely attracted."

Which brings us to perhaps the most important question: how can a therapist tell the difference between an OCD sufferer experiencing intrusive and irrational sexual thoughts, and a person going through a difficult process of sexual realisation?

"You'd make an assessment," says Joseph, who practices a variant of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy called Rational Emotive Therapy. "You'd ask questions about whether they find men sexually arousing, or whether they have wet dreams about men, and whether they are excited by the idea of sex with men.[…] If the assessment is that the person is not gay, because you believe as a therapist that there is no evidence, that does not mean they have internalised homophobia. They're just asking themselves: why did I have this thought?"

And the treatment?

"The person who has OCD is highly anxious about this obtrusive thought. Once they accept the thought, then it becomes apparent that their OCD disappears. Instead of fighting the thought, they've accepted it without adding any meaning to it. The whole therapy I practice is based on acceptance."

And what if it turns out that the patient is gay, after all?

"If someone is fearful of being gay because being gay represents to them abandonment by their family, or rejection, or experiencing violence or abuse, then you would help them to accept themselves unconditionally as a gay man."

Ironically, acceptance rests at the heart of both sides' arguments; acceptance of thought, sexuality and self. And it's impossible to know how far apart people actually stand on the issue, given the way that the controversy blurs the debate.

"If the path to treatment is facilitated through an online community that has coined a theme called HOCD, how is that hurting people?" argues Aaron. "Online communities sharing common experiences to better understand their condition is critical to a global society."

That being said, he stresses that an OCD diagnosis from a clinical psychologist is vital. "Remember, everyone has intrusive thoughts about sexuality. So intrusive thoughts about your sexual identity alone are not enough to know you have OCD."

Ten years and two psychologists after that first, fraught experiment with gay porn, Darren still suffers recurring bouts of OCD, but not around his identity as a straight man. "My anxiety can be fueled by a lot of stuff, but I just do the same thing I was taught to do with fears about sexuality.

"Accept it, let the thought pass, and move on."

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

Check out other entries in our series on sex & relationships below:

- How to get off dating apps and meet people in real life

- Why we need to stop trying to make 'date night' happen

- What does it mean to be charming? And how does one acquire it?

- What it's like to attend a 'pick up artist' class run by a woman

- It's time to confront porn's biggest tattoo

- Meet the straight men who are terrified they are gay

- Why can't men stop sending dick pics?

- What it's like to be in an amateur sex cam couple?

- What it's really like to be in an open marriage

- The last hour inside the masquerade party at Snctm sex club

- How the virtual reality porn revolution is going to change your life

- A guide to staying in lust

- Why thousands of young men are giving up on pornography

- 7 people reveal what it's like to use a threesome app

- The best sex movies: a countdown

- 'Game of Thrones' actor John Bradley does a bedtime reading of Jon Snow's infamous cave sex scene