Lunch with Barbara Charone is a blur. A two-bottler at The River Cafe. Or was it three? Whatever the final count, this was one of those merry sessions that stretches deep into the afternoon. The idea was to talk about her recent memoir, Access All Areas: A Backstage Pass Through 50 Years of Music and Culture, but we covered a lot of ground besides. Blood pressure. Call centres. Antigua. Lockdown. Chelsea FC. More bloody Chelsea FC. (She’s a fanatic, and sits on the board.) People who are rude to waiters. People we hate. People who are rude to waiters and who we hate. Keith Richards’ shepherd’s pie. Drugs. Rosé. Her love for Rod Stewart. And Elvis Costello. And Keith Richards, obviously.

BC, as she is universally known, was one of the great rock scribes of the Seventies, before she switched sides to become a PR. As a reporter she worked for the famous names of the rock press, in the heyday of music writing: Rolling Stone, Creem and Crawdaddy in the States, the NME and Sounds over here. As a PR she is legendary, looking after not only Keith and Elvis and Rod, but also Elton John, Madonna, Robert Plant, the Pet Shop Boys, REM, Depeche Mode and the Foo Fighters.

So many questions, so little time, and rather too much booze. That’s the problem with BC. Within a few minutes of first meeting her, you feel as if you’ve known her for years, and before long you find yourself pouring your own heart out, revealing your deepest, most shameful secrets. You can tell her these things because BC has seen and heard it all.

Her voice is both mellifluous and husky, her anecdotes punctuated by the most throaty and joyous of cackles. She talks of a comfortable, happy childhood in the 1960s, mainly spent in Glencoe, “a snug middle-class suburb” of Chicago, not too far from Lake Michigan. Her father was a lawyer, her mother a drama teacher. Free time was spent at Chicago’s Auditorium, watching the Doors, Joni Mitchell, the Band, Jackson Browne and Joe Cocker.

Her first working gig, for the Chicago Sun-Times, in 1971, was James Taylor. She moved to London in 1973, writing for the NME,“mostly stuff no one else wanted to cover”: Hawkwind, Genesis.

“Female rock critics were extremely rare back then,” she says. The bouncers could never understand why a woman would come backstage for any other reason than being a groupie. But the access to stars at that time was amazing, “something that rarely happens these days”. She remembers a day in Oxford when Paul McCartney suddenly decided to grant an interview. All she had to hand was a copy of Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop, so she scribbled down McCartney’s quotes in the margins of the book. “Talk about life imitating art!”

She got off to a bad start with Keith Richards. She had flown to Munich hoping for an interview for a Crawdaddy cover story. She found the Rolling Stones guitarist “smart, funny, honest and charismatic”. She was pleased with the piece. A few months later, she paid Richards a visit in New York. Ushered up to his suite, “The first thing he said to me was ‘where do you get off writing we’re going to break up? Who gave you that idea? Who?’ He was mad.” The problem was the end of her piece, which quoted lyrics from the Stones. “Time, however, waits for no one — not even the Rolling Stones,” she wrote.“This could be the last time/Maybe the lasttime/I don’t know.” She had to apologise. “I had tried to be clever.” Lesson learnt.

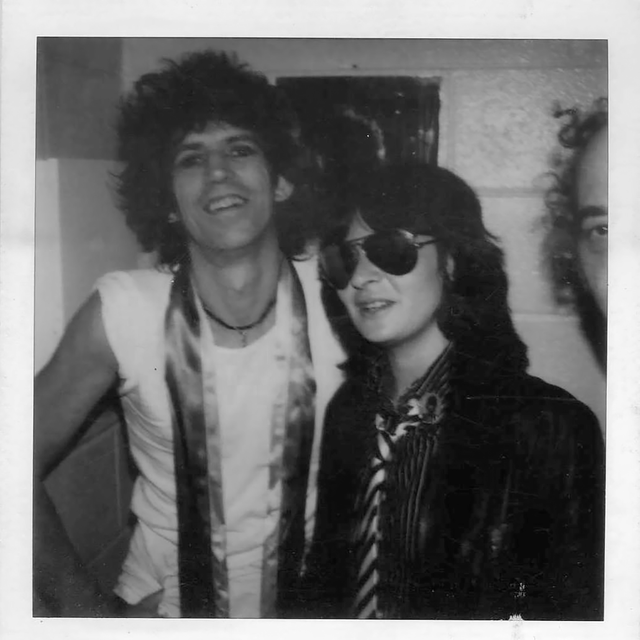

By the mid-Seventies she and Richards had become friends. He authorised a biography, which she was working on at the time, in 1977, that he was arrested for heroin possession in Toronto. His passport was confiscated and, while the rest of the Stones flew to New York, Keith stayed in Canada with Anita Pallenberg and their young son, Marlon. BC moved into the suite next door. “When Keith Richards walks into a room,” she once wrote, “rock ’n’ roll walks in after him.”

One of the telling things about the new book is how discreet it is. “Everyone thought I was going to spill the beans,” she says. “But it’s just about me.” The nearest you’ll get to any kind of gossip, on the page, are lines such as, “Keith often stayed at The Savoy and there were many nights over the years where I left the hotel in something of a fuzzy state of mind...” Or, on spending time with the Stones and the Saturday Night Live cast of Belushi, Aykroyd, Murray et al, in New York in 1978: “Suffice to say, there were a lot of late nights.”

That of course, is the mark of a great PR. Discretion. She’s happy to tell tales of smoking too much Jamaican weed with Toots. “All I could understand him saying within a few puffs was: ‘Praise the Lord! PRAISE THE LORD!’” Or admitting that, “At this point I must confess that by now I had developed quite a fondness for cocaine.”

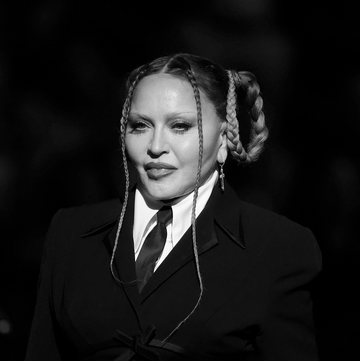

She has a special love for Madonna, whom she represented right at the start. “Madonna is funny, has a great sense of humour. She so doesn’t get enough credit. She should be cherished.” And she adores the Foo Fighters, who she still looks after. “People always ask if Dave Grohl really is that nice. And the answer is yes. The whole band are great, good people. They’re old-school, in that they let people come into their world. Dave says, ‘Here’s our dressing room, help yourself ’.”

But she’s cautious of getting too close to her clients. “You’d be surprised how many people who work in the music business make the mistake of believing the artist is your friend.” And she’s rightly defensive about the skills a good music PR needs, being both confidante and whipping post. “What we do involves a lot of thought and care,” she says. “And when I hire people to come and work for me, I have no interest in the kids who only want to come to the after-show party. I want them to love music.”

Because that, for her, is what it’s all about. Not the private jets, limitless narcotics and raucous parties, the backstage passes and personal mix tapes from Keith (although those are certainly appreciated). “During lockdown, whenI wrote the book, I just fell in love with my record collection again.” Her passion for music is infectious, her knowledge encyclopaedic, from her adoration of The Kinks (“utterly timeless”) and The Band, to her favourite Stones album (“Exile, always Exile”) and admiration of the new Father John Misty album.

She takes a last sip of wine, and stands as if to go. Then turns to me with the broadest of smiles. “I just loved music. I still do. And that’s why I still have a career.” With that, she’s off, as modest as she is magnificent, disappearing into the sunset. Hammersmith, though, not Waterloo.

Tom Parker Bowles is editor-at-large for Esquire. This story appears in the Spring 2023 issue of the magazine, out now