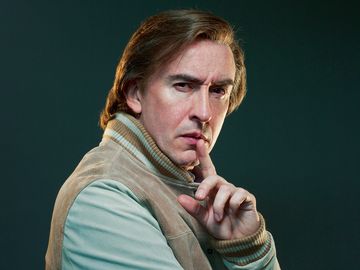

His outfit is nothing less than extraordinary. A knitted jumpsuit, top-half red, bottom-half oatmeal, a little tattered, with extravagant turn-ups at the ankles, and square, pearlescent buttons at his neck and crotch. He’s thinner than you might expect; above his collar his head is fair, a bit scruffy, showing the wear of six decades of existence, and he returns your gaze with an open, inquisitive expression and questioning, pale eyes. His pupils, when they catch the light, are so black they look like beads of glass, which is also what they are.

“Alan Measles. He’s as old as I am. He’s 60. He’s my childhood teddy bear,” the Turner-Prize-winning artist and Bafta-Award-winning broadcaster Grayson Perry pronounced on the first episode of Grayson’s Art Club, which began on Channel 4 in April last year when the first lockdown was in full swing. He held the ragged bear up as he talked to one of the half-dozen cameras that had been installed in his North London studio to make the TV series: “Named after a disease, because we bonded when I was about three and I had measles. So he’s the perfect candidate for a protective spirit in the middle of a pandemic.”

Perry was introducing Alan Measles in order to explain a piece that viewers would watch him make over the show’s six episodes: a two-foot-high ceramic incarnation of Alan with hands on hips and an oversized, kidney-shaped head. Like much of Perry’s work, it hinted at his wide-ranging, ethnographic interest in artistic practices: in this instance, perhaps, African power figures, or Hopi katsina dolls. Perry would gradually cover the sculpture with prongs and shards of scavenged iron stuck on with Araldite, so that — again, something often true of what he makes — it looked simultaneously threatening and appealingly cartoonish. “What would be in the middle here?” Perry asked no one in particular, looking at a rectangular cavity in the ceramic Alan’s stomach. “We don’t know. Maybe there’s room for a vaccine.”

Those familiar with Perry as an artist might know Alan well — he has cropped up frequently over the years, on pots, in tapestries, as sculpture; Perry has even driven him around Europe encased in a glass shrine affixed to the rear of a custom-built motorcycle — but no pre- knowledge was expected for Grayson’s Art Club. Perry’s name may have been in the title, but the show was not about him and his oeuvre; or rather, not only. For most of it, Perry acted as an amiable host, chatting through his laptop with artists (Maggi Hambling, Antony Gormley), comedians (Noel Fielding, Jim Moir) and members of the great British public about art they had been making in isolation including, from the nearly 10,000 submissions the show received, a woman who sculpted a clay head of chief medical officer Chris Whitty, and a man who made a portrait of Perry out of noodles and soy sauce.

Intercut with the interviews was footage — captured on the remote-controlled cameras operated by a film crew camped outside; the director, Neil Crombie, relayed instructions through the window — of Perry and his wife, the psychotherapist and author Philippa Perry, with whom he has a grown-up daughter, Flo, as they went about their business. In real life, away from the cameras, Perry usually works alone, but for the show we got to enjoy Grayson and Philippa — he calls her “Phil”, or “Philbert” — pottering about his studio, making artworks (Philippa is also a skilled ceramicist), drinking coffee and discussing their enigmatic cat, Kevin.

As we ricocheted between boredom and fear in the first lockdown, for those who watched it the series was something of a salve. It reflected the strange lull we all felt, when the structures and expectations by which we’d hitherto been conducting our lives had been revealed as faulty if not outright fallacious; and it gave us something to do with our unmoored feelings and nervously drumming fingers: make art! (As I write this, I’m looking at a small bird I made out of clay and painted with nail varnish during an idle/desperate lockdown moment; it’s undeniably rubbish but I made it, and who’d have thought it?) Grayson’s Art Club was, of its kind and for its time, perfect telly. It also made Perry — alongside fitness instructors on YouTube, amateur bakers on TV and quickfire comedians on Twitter — into one of the unlikely heroes of the pandemic. Not quite a protective spirit like Alan Measles, but certainly a comforting presence.

Just to remind you, this is the same Grayson Perry who came to notoriety as the “transvestite potter” (a reductive yet highly marketable term he has not been shy of using himself), who decorated the beautiful objects he made with his darkest thoughts; who accepted the 2003 Turner Prize as his female alter-ego, Claire, dressed in a pink baby-doll dress and frilly ankle socks; who has thrived both within and in opposition to that most rarefied of industries, the art world. Here was Grayson Perry on the cusp of becoming a cosy, cuddly, national treasure. Who’d have thought that either?

In an outfit that is, by his own standards, decidedly ordinary— a fluffy, zip-up fleece covered in multicoloured flowers — Perry ponders his own latest incarnation. “I’m coming into my what some people call the ‘beta adult phase’, which is when you reflect on your life more and you’re not so competitive,” he says, in the forthright tone that he has honed through years of lecturing and public speaking. “Maybe I’m becoming softer — people around me at the moment wouldn’t say that because I’ve got a bad back — but I’m coming to the realisation that I might be nice. I never held myself as a nice person for most of my life. I always thought I was a grumpy shit. I can still do grumpy shit really well, but I think I’m coming round to think, ‘Oh, maybe you’re not such a bad old stick, Gray.’”

Our conversation happens in late autumn, which, thanks to the imminent threat of a second lockdown, is rearranged at the last minute to take place not in person at his studio but on Zoom. Perry is clearly pleased with the response to Grayson’s Art Club, which led to a Christmas special, an exhibition currently installed at Manchester Art Gallery (suspended due to national lockdown restrictions as this issue went to press), and will return for a full second series this month. Unlike previous factual TV shows he’s done, it brought him to the attention of a pre-watershed audience, and while he was a little bemused about some of the comments about his marriage (“People would say things like, ‘Ooh, relationship goals!’”), he took it mostly in his stride. “I’m pretty used to being on camera now, you know, and I’m an open book, so I didn’t really worry about it. And I trust Neil to edit out any of my non-national-treasure behaviour!” he says, breaking into his signature Gatling gun laugh.

For Perry, the consoling aspect of making art, one of the main themes of the show, was not a revelation. “For me, it’s always been a comfort,” he says. “I think it’s dangerous when people think they’re ‘being expressive’. Yuck. It’s like people who say they’re ‘spiritual’, innit. You make the work you want to make, and you get on with it and hopefully it connects with other people. Obviously now I’m aware, as a successful artist, that people are interested in what I’m up to, and so I do have this feeling of having a kind of amphitheatre in my head. But I went to art school because I liked making art, not because I had something to say.”

Perry and his younger sister, Helen, grew up in Chelmsford, Essex, the children of Jean, a solicitor’s secretary turned housewife, and Derek, who worked in an engineering factory and as a part-time waiter. When he was five, his mother had an affair with the milkman and his father moved out. “When he left I felt bereft,” he told his friend, the author Wendy Jones, for her 2006 book, Grayson Perry: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Girl. “As far as I am aware, it is the event that has had the largest impact on me in my life.”

The milkman, Alan, whom his mother later married, turned out to have a quick, violent temper. Perry sought refuge in an increasingly complex imaginary world of fantasy islands, marauding Germans and Lego vehicles, later giving way to Airfix aircraft, all overseen by his charismatic and all-knowing teddy bear, Alan Measles. (He named him Alan, he tells Jones, after an older boy who lived next door, rather than after his stepdad, to whom he refers in the book as “the old man” or sometimes just as “the milkman”.)

Does he see that period as his starting point as an artist? “There’s a direct line of ancestry going back, probably starting with Lego and then Airfix,” he says. “The relationship between the fantasy world, the physical making, and the world outside that is affecting you: that was implanted in me, that relationship. I was with my teddy bear and my models in my bedroom, and yet outside was my family life thundering on. In my mind, there was a kind of cocktail formed that is still the same cocktail I drink now. Now I drink it as that artist bloke on the telly who puts on frocks, but the cocktail is still the same cocktail.”

Perry made his first coil pot when he was eight or nine, under instruction from a vicar’s wife, but was more struck by the sensation of the rubbery smock he had to put on to make it; it was in early puberty that he began experimenting with bondage and wearing women’s clothes, a facet of his identity for which he is now at least as well known as his art. It was only at his sixth-form art teacher’s suggestion that Perry went to study art at Braintree College of Further Education and then Portsmouth Polytechnic, though he took a while to emerge from his shell. “I was sort of mute when I went to art school,” he says. “There were two girls there who thought I was German because I only grunted.”

He began making ceramics in earnest after college in his early twenties, when a friend suggested he give it a try (still today he coils his pots rather than throws them on a wheel, the technique shown to him by the vicar’s wife). Pottery seemed an improbable choice for Perry, who had been more interested in film and performance: he and some fellow squatters had formed a “Neo Naturist” troupe, who’d lark about in body paint in front of not always enthusiastic audiences. Yet the idea of a medium that was not only uncool but also floggable — of entering the gallery through the gift shop — had a gleefully subversive appeal. “Early on, my way of teasing the art world was by playing at being accessible,” he says. “Like making pottery: I thought people would buy that for Christmas presents.”

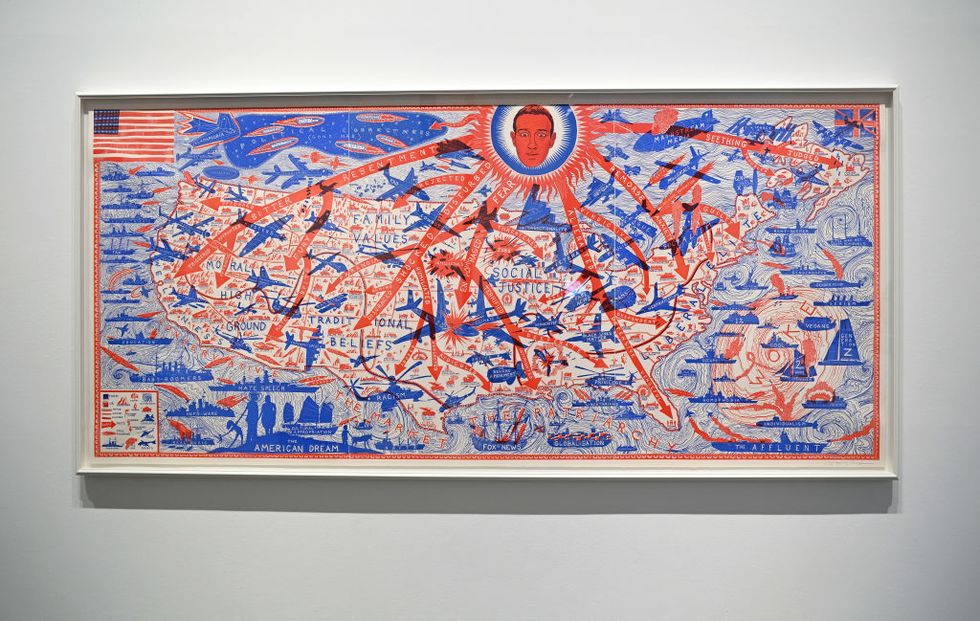

There were two solo exhibitions of Perry’s work in Britain last year. The first, The MOST Specialest Relationship, at the Victoria Miro gallery in London, was a collection of ceramics and paintings inspired by some motorcycle journeys he’d made across the United States — Perry is an avid biker — which also became the subject of a recent Channel 4 series, Grayson Perry’s Big American Road Trip. The ceramic pieces in particular were spectacular: a turquoise replica of an ancient Persian pot decorated with the black oblong silhouettes of slave ships, between which faint visions of Donald Trump’s face loomed; a vase in a traditional Islamic shape, shattered and restored with gold veins in the Japanese kintsugi style and inlaid with tiny, drone’s-eye-view rows of planes and trucks and grave markers. These were gleaming, polished works by a practitioner in full control of his message and his medium.

The other exhibition, at The Holburne Museum in Bath, was of Perry’s early work, made between 1982 and 1994, called The Pre-Therapy Years (Perry likes a no-nonsense title). On a wall in the first gallery was a large photograph of him in his Neo Naturist days, smeared in red and blue body paint with a bell tied to the end of his penis. The exhibition itself included darker, rougher pots engraved with images of masturbating adult babies and swastikas and devils and gaping vaginas; one of the earliest works was a tiny throne-cum-commode inspired by the cult of Princess Diana complete with a tiny turd (“I had tried to encase one of my own faeces in a block of resin, which ended in a smelly mess,” Perry explained in the text below the vitrine, “so I made a fake one out of ceramic”). If anyone did buy one of his pieces as a Christmas present back then, they were very brave (and wise: in 2017, a pair of vases Perry made in 1996 called “I Want to Be an Artist” sold at Christie’s for £632,750).

Putting together the Holburne Museum exhibition (which, pandemic permitting, should have moved by now to The Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich) was a chance for beta adult Perry to reflect on the artistic output of his younger self. “I’m more generous about it now than I would have been just after I made it because I was quite harsh on myself. I was quite angry and I was unaware, I suppose, of what was going on for me,” he says. “But in some ways, that’s good if you’re making spontaneous artworks. It was more chaotic and more self-centred. Ha! So that’s a pretty good reflection of what was going on for me then.”

The overwhelming impression of walking around The Pre-Therapy Years was of an artist with a lot of raw, unprocessed feelings and a playful but troubled mind. “People were kind of a bit scared of me in those days,” he admits, “and I could be pretty sharp. Just for fun, you know? Not that I’d make people cry necessarily, but I think I was quite scary. Because I was uninhibited. I was uninhibitedly bitchy. Ha ha!”

As the exhibition title does not shy away from implying, it was the therapy he began aged 38 — at the suggestion of Philippa, whom he met on a creative writing course and married six years earlier in 1992 — that enabled him to confront some of his adolescent experiences head on. He broke contact with his mother in 1990 and, when she died in 2016, he did not go to her funeral. It was therapy that brought Alan Measles back into the foreground “as a carrier, an unconscious symbol and metaphor for so much for me”, and therapy that enabled him to embrace his transvestism more openly. One thing that therapy has been really good for,” he says, “is that it makes you more aware of what’s impacting on you emotionally: what stuff is coming onto your satellite dish, what’s annoying you or what you’re enjoying.”

Perry seems also to have an innate ability to step back and see a bigger “satellite dish”: to examine the live feed of cultural tropes and habits and hypocrisies that affect us in real time, but which aren’t always easy to understand in the moment. It might have been the tyranny of Margaret Thatcher in the early works shown in Bath, or the tyranny of Mark Zuckerberg in the recent ones in London, but his sensors seem always to be finely attuned. As he puts it: “I’m always on the lookout for where the tender spot is in culture.”

In 2003, Perry won the Turner Prize (prize money £20,000) for his shows at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and at the Barbican Art Gallery in London. In February last year, he won the Erasmus Prize, the first British artist to do so since Henry Moore in 1968 (prize money €150,000). Nevertheless, for much of his career the art world bore the brunt of his excoriating energies; in the Reith Lectures he delivered for Radio 4 in 2013 — the first visual artist to do so — he skewered the notions of “quality” and “seriousness” in the industry: “There’s an awful lot of guff talked about art,” he proclaimed. Though he has been known to quote the late artist Nam June Paik’s aphorism, “The artist should always bite the hand that feeds him — but not too hard”, he remains largely unrepentant.

“The art world has a long history of cheekiness going right back to the 19th century pretty much; even Hogarth used to sort of take the piss out of the Royal Academy,” he says. “So I think being a kind of contrarian is quite healthy in the art world.” He has also, perhaps, derived a certain pleasure from the idea of himself as a one-man populist sleeper cell (“The mafia has even let me in!” he told the audience of the first Reith Lecture at Tate Modern).

In recent times, his target has widened. In 2012, he presented a three-part documentary series for Channel 4 about taste, and has since made others — all with Swan Films, who made Grayson’s Art Club — about identity, masculinity, rites of passage, Brexit, and the recent series about America, in which he considered the cultural fault-lines that divide that country and how they play out as a fainter echo in our own. Like pottery, television seems to appeal to his sense of disrupting the established cultural hierarchies.

“It used to be sneered at by the cultural snobs, you know, as the kind of one-eyed god that corrupted our youth, and now it’s the gold-framed literature of our age,” he says. “Other people, clever academics or other artists and cultural people, are operating on the same sort of issues, it’s just that we have that most annoying capacity to make them go mainstream!” He breaks into a raucous laugh. “Which people who are rarefied, cultural-elite intellectuals hate; people who write the very difficult, impenetrable books, they hate the person that reads that and then makes the TV programme about it.”

He tells me he’s just finished a piece of work but won’t tell me what it’s about — “it’s all under wraps: a surprise and reveal!” — though he admits it relates to another “big arching concept” of the kind he likes to explore. If I had to hazard a guess, it would be that it’s about whiteness, perhaps his own; at one point he tells me: “If you’d asked people in the past, ‘Who has identity?’ it’d be like, ‘a Black lesbian in a wheelchair’. You don’t hear white, middle-aged, middle-class men talking about their identity that much.”

With his knack for extrapolating comprehensible themes and his engaging, unpretentious delivery, Perry has proved to be a TV natural: two of the series won Bafta Awards and four of them received nominations (this year’s nominations, for which his American road trip show would be eligible, have not yet been announced). Somehow, Perry has turned himself into a voice of clarity in a confused age, a contemporary chronicler in crinoline, our very own — and he can have this one — Little Bo Pepys.

In 2011, perry curated a major show at the British Museum, The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman, displaying his own work alongside objects from the museum’s archives. In the same year, he was elected to be a Royal Academician, and in 2018 he curated the 250th anniversary summer exhibition at the Royal Academy in London; at the press view, I joined the other attendees in trailing around after him like rats after a piper, as he gave a tour of the exhibition in a purple wig and pink clown suit covered in pictures of his own face. In 2014, in a midnight blue “mother-of-the-bride” skirt suit, he was appointed a CBE for services to contemporary art. For someone who once set himself up to rankle the establishment, he is now very much part of it.

Still, something about the “national treasure” tag doesn’t sit quite right. It brings with it para-meters of expectation against which, you suspect, Perry might strain. His opinions are not always popular: in an interview with The Arts Society Magazine in November last year, he said that Covid-19 might clear “a bit of dead wood” from the culture sector, which created a small furore (he later stated on Twitter that the news media had taken the quote out of context). Sometimes, for all his good intentions, his insights can seem basic, as in the first episode of Grayson Perry’s Big American Road Trip, recorded before the death of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement, in which he interviewed Black people in the South about race. (He concedes he might be “more cautious… too cautious” to make that programme again now.)

He seems also to thrive on a sense of opposition, real or perceived. Even a discussion of what he’s watching on TV during lockdown — Schitt’s Creek, Call My Agent, Strictly Come Dancing — leads to a take-down of the legacy of “left-wing theatre” and “this idea that you have to be incredibly meaningful and right-on and depressing. Laughter is as complex and profound as sadness. The left wing think because they’re being meaningful and profound and progressive that they’re the top of the tree, but they’re not. I’m glad those [kinds of] programmes are on the telly but I don’t want to watch one when I’ve had a glass of wine.”

If there’s a slight air of tilting at windmills, Perry’s not unaware of it. “It’s just finding new ways to be contrary nowadays is so difficult,” he says, in a luvvy voice, “everything’s been done!” Sometimes his contrariness can be a little bit delicious too: when he went on Desert Island Discs in 2007, the first track he requested — the first track — was “Loser Kid” by the cod-rock Noughties’ boy band Busted (he told Kirsty Young he was hooked by the opening lyrics: “I was always picked last for teams / I wore my sister’s jeans…”).

As I look at Perry on my laptop screen — a box into which, for once, he fits comfortably — and he looks back at me, it is difficult to come away with any definite sense of him, and I don’t think it’s just the technology that does it. He gives lively, quotable answers to my questions, but I don’t feel in any way qualified, after it finishes, to describe “what he’s like”, other than to say that he seems like someone who is very used to giving interviews and is very much in control. (If his bad back is making him grumpy he manages to seem cheerful, though perhaps only just: “I’m a 60-year-old with a catalogue of symptoms to talk about if you want to be bored,” he says.)

In late November, he announced a live theatre tour for autumn 2021 called, no doubt with some irony, A Show for Normal People. Right now though, he is doing a version of what the rest of us are doing: hunkering down with his wife and his cat and a glass of wine, nursing his bad back and watching Strictly (“I’ve always been a fan and wanted to go on it; I think they asked me but it didn’t really work out, but at the moment I couldn’t even pick up a book let alone a partner so I’m quite glad”). Claire hasn’t been around much of late — “I’ve got no audience, you see” — and Covid put paid to the opening party for the Grayson’s Art Club exhibition in Manchester in November which, he says, “would have been a shoo-in for a good frock.”

Alan Measles hasn’t been around so much either, but when the time comes for the second series of Grayson’s Art Club, or when we next need a protective spirit — whichever is the sooner — Perry will bring him out again. For now, Alan is back at home in Grayson and Philippa’s bedroom, just as he used to preside over Grayson’s childhood bedroom many decades ago. “That’s a safer space for him. It’s a bit dirty here and too much light,” says Perry, gesturing around his empty studio. “He is 60 so he’s a little bit fragile. I don’t want him to get completely crumbled to dust.”

Grayson’s Art Club returns to Channel 4 this month

Miranda Collinge is the Deputy Editor of Esquire, overseeing editorial commissioning for the brand. With a background in arts and entertainment journalism, she also writes widely herself, on topics ranging from Instagram fish to psychedelic supper clubs, and has written numerous cover profiles for the magazine including Cillian Murphy, Rami Malek and Tom Hardy.