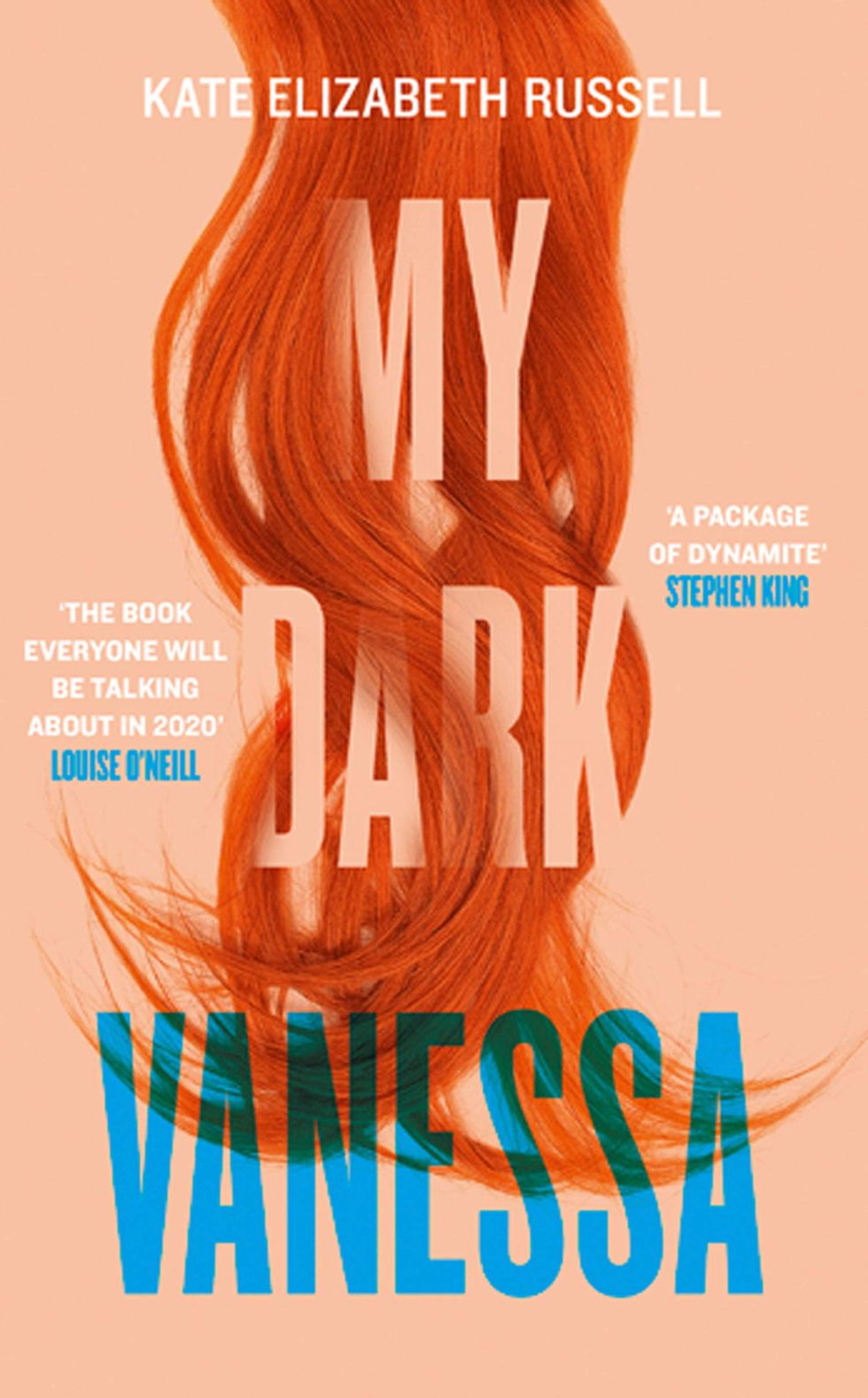

Some characters linger with you long after the last page, almost as though you can feel the afterglow of them in the room with you. Vanessa Wye, the protagonist in Kate Elizabeth Russel's novel My Dark Vanessa is that sort of character, her story one that lures you in and doesn't let you go

In Russel's debut we find Vanessa thrust into a new world when she gets a scholarship for a prestigious boarding school. Quiet and solitary, she forms a bond with her English teacher, Jacob Strane, and he stealthily steers her into a sexual relationship which further isolates her. Strane is an expert at twisting the dynamic so he seems powerless and decisions appear to be in her hands, as he tells her at one point, "I would never have done it if you weren't so willing."

Sixteen years later, as a #MeToo-style movement is swelling, other victims come forward and Vanessa is forced to reckon with the abuse that was central to the relationship and consider whether to speak out.

Russel's book, which author Stephen King described as "a package of dynamite", never lets up. It also asks difficult questions about abusive relationships and refuses to avoid the uncomfortable issue of complicity in grooming.

It's a story which, like Lisa Taddeo's 2019 book Three Women or the viral New Yorker short story Cat Person, is primed to start debates between readers for its daring perspective and commentary on power dynamics between men and women. Like these works, My Dark Vanessa feels inextricably linked to the #MeToo movement, with Russel amending aspects of the story after the allegations about Harvey Weinstein broke at the end of 2017. It even becomes entwined in the Hollywood producer's court case in an unexpected way.

Its publication has also had its own share of controversy, with Russel accused of plagiarising Wendy Ortiz's memoir Excavation and pushed to share whether the novel was based on her own abusive experiences, reigniting the debate about who is able to tell which stories. The fallout saw the book dropped from Oprah's bookclub and Russel quit Twitter.

Earlier this week she spoke to Esquire over Skype call, discussing how #MeToo intertwined with her writing process, the difficulty of being asked to prove your own trauma and why it was important for her to show that coming forward isn't the only path for victims.

Esquire: Where are you now and what are you doing to keep busy while in isolation?

Kate Elizabeth Russell: I’m in Madison, Wisconsin in the middle of the US I moved here last January with my husband who is an academic at the university here. I’m doing interviews which have been keeping me busy, but also binge-watching Netflix and doing puzzles in self-isolating way that everyone is right now.

I’m having trouble concentrating but I’m hoping next week to settle into a routine where I read and write every day. It doesn’t make a difference if I check the news ten times a day so I might as well pull back.

ESQ: Have you had to make big changes to your publicity schedule because of the Coronavirus?

KER: I did a launch event on the US publication date on 10 March and then didn’t have that many other events scheduled because we were going to see how the book did. For the UK launch I was doing events in London and the north of England and then a couple in Scotland which all had to be cancelled, which is disappointing, but at the same time it’s easy to keep perspective because this is so big, bigger than a book.

ESQ: You wrote My Dark Vanessa over a very long period of time, can you talk about the process of writing it?

KER: I can trace the seed of the story back to the first time I read Lolita when I was 14. It was one of the first novels which spoke to me as a writer and I fell in love with it. I identified with her in a lot of ways and read the novel looking for glimpses into her which are there if you read it closely. I also saw in Lolita a certain insight into how the world worked, I’d heard the term before and knew what it meant as a trope of a teenage seductress. I saw evidence of that in the culture I was living in.

ESQ: That’s a huge period of emotional and physical growth that you were writing the book over, how did it change over the course of your writing?

KER: When I was younger I saw it as a love story, but my idea of what a love story could be left a lot of room for abuses, darkness and obsession. I was a bookish kid and loved Brontë novels. I thought Wuthering Heights was the height of romance and that is certainly a story with obsession and violence. It wasn’t until I was in mid-to-late twenties and I learned more about how symptoms of trauma can manifest in a person, especially prolonged trauma from sexual abuse, that I started to see it differently. The more I learned about that the more I recognised Vanessa, and so it was a matter of still holding onto this idea of it being a love story – because that’s something Vanessa clings to in the novel – but also understanding what PTSD can do to the brain and body.

ESQ: There are lots of instances where Strane talks about the power Vanessa has over him and similarly Lolita presents something alluring about having power over older men, do you think that power is real?

KER: I tried to look at this idea of power and how the the power Strane says she has over him can be an illusion. I think that’s certainly a way to read my book, seeing whatever power Vanessa believes she has to be flimsy and superficial. I also wrote it questioning whether power should be something that we’re aiming in a romantic relationship anyway. Maybe that’s a little too abstract but I think that’s a really good way to frame the book. When Strane makes the early moves toward Vanessa he’s so subtle and slow, but it’s easy to understand why she views that as just seduction because I think there isn’t a lot separating grooming from seduction from the victims point of view.

ESQ: You finished writing as the #MeToo movement was unfolding, how did that change the book?

KER: The book sold at end of October 2018 so a year after #MeToo really exploded. I already had a present day plot-line with another girl coming forward and accusing Strane of abuse when the stories about Harvey Weinstein broke and #MeToo really took off. I didn’t know what to do, it was such a striking parallel. At first I tried to ignore it and kept my head down and didn’t really bring it into the writing process at all, but as #MeToo got bigger and bigger, and as I saw more and more people sharing their stories, I saw that so much of the conversation focused on these questions of consent and complicity that were so central to the book.

I decided to do a bit of revision, having another student coming forward as part of a movement not a single voice. In some of the scenes with Vanessa and her therapist I had the conversations centre more on Vanessa’s reactions to this unnamed movement in the novel and her take on all these women coming forward and speaking out. It felt risky because I never imagined myself writing a timely novel. I was afraid that it would seem opportunistic or that the timeliness of it would cheapen the work somehow, but those were anxieties about the way the book would be received rather than worries about the book I had written.

ESQ: With the recent Harvey Weinstein conviction do you think that’s a line in the sand for powerful men abusing people?

KER: There was actually a surreal moment during the trial when they tried to kick a juror off for having read my book, which was not something I had ever imagined. On the one hand it is a victory because so few rapists get convicted and powerful men rarely rarely do, but at the same time looking at the particulars of what he was convicted of and one woman’s rape accusation being thrown out, it just shows how woefully inadequate the system is for giving us the definition of what happened and what didn’t.

ESQ: Have the successes of recent works like Cat Person or Three Women reassured you that people want to hear these kind of stories?

KER: It is heartening to see that the subject matter is something people want to engage with. Specifically with Cat Person, what struck me when that came out and went viral was how many people were reacting this way to a piece of fiction. I felt like it made a lot of sense because you’d been getting all of these real-life trauma narratives which can be so tricky to interact with because that’s someone’s real story of harm, and so using picking apart those stories can feel very uncomfortable and unethical.

If you centre your conversation on a piece of fiction there’s a lot more freedom as a reader to criticise the characters, because they’re not real. I thought about that a lot when Cat Person went viral, I do have similar hopes about my book and that’s part of the reason I’ve been so insistent about it being fiction, because it is a story I created but also because I think it being fiction is really important to the reading experience.

ESQ: Have you had to clarify this isn’t your story and is a fictional one?

KER: It’s a fine line because in a lot of ways this is a personal story and there are a lot of parallels between Vanessa and I. I knew going into this that there is a tendency to read debut novels, especially those written by woman, as autobiographical. A lot of those questions come from a place of curiosity, which I do understand. I think it’s understandable to read a book and wonder if the author’s real life is in there, but at the same time it’s fiction and there comes a certain point where I don’t know what else to say.

ESQ: People were asking you to share your own traumas to prove the authenticity of the book, was that difficult?

KER: I had spoken in interviews back to when the book had been announced at the end of 2018 that it was fiction, but that I did have experiences as a teenager that informed the writing. Also I put out there that I’d been working on the book for all that time, but these questions about authenticity kept coming up and things I’d already been on the record as saying weren’t making its way into that conversation. It was frustrating because I felt put in a position a few weeks before the book launch where I had to come out and restate these things at a moment where there was a lot of attention on me. It’s disheartening that you have to think this way as a writer but it's something you have to do going into the publication process when you’re writing a book with this subject material.

ESQ: I find it really interesting that despite the number of people that have come forward with stories of various types of abuse, people are still forced to prove their pain and relive the trauma of what they’ve been through, as if we haven’t all learned how universal it clearly is?

KER: Absolutely, I feel like it makes more sense to just assume that every person has some experience of this and then let us all use our experiences in whatever way we want, whether it’s art or something else.

ESQ: This book lets Vanessa find some peace which is a strong message for survivors of abuse, is that what you wanted to give people?

KER: It was really important for me to give Vanessa that sense of peacefulness and a bit of hope. It’s interesting, hearing from readers that they hoped maybe Strane would be brought to justice or that Vanessa would speak out. I think that’s understandable because that’s the narrative we’ve come to expect from #MeToo. I viewed that ending as a way for Vanessa to still be focused on him and I wanted to let her have a future that was centered on something hopeful and good. It was important for me to show that speaking out publicly isn’t always the right path forward, it certainly isn’t the only path forward.

ESQ: Strane’s character feels compelling rather than a cartoon villain, how did you balance writing someone that Vanessa could fall for but who is still clearly an abuser?

KER: There were points when I was working on the book that he did become a one-dimensional villain. It was easier in a lot of ways to write him like that because I didn’t have to think about him too much or give him depth. He wasn’t necessarily a character I wanted to spend that much time with. I realised that by writing him that way I was cheating Vanessa, because if he was obviously so bad then the reader would have trouble sympathising or relating to her. Making him compelling enough for the reader to understand what she does was my way to give her her humanity.

ESQ: The sex scenes have this quite gross, stomach-turning quality to them but you could see how someone who was young or naïve would see them as loving, were they hard to write?

KER: I would say they are more difficult for me to read now, because I was so deep in Vanessa’s perspective so the way that things skim along the surface was sort of how I had to write it. That was the approach I took when I was writing it, but it was hard, there were days where I felt totally physically exhausted as though I’d spent all day working out when I’d just been sat at my desk. It took a toll on me. I tried to write those scenes in a way that the reader would see them as instances of abuse but to someone young, who had been raised to expect sex to not necessarily be pleasurable or comfortable, they might just see them as sex, not abuse. That’s the most heart-breaking thing.

ESQ: Vanessa is out of place at her school which makes her an easy victim for him to pick, do you think this might not happen to someone who was more protected than her?

KER: Absolutely, that was very much deliberate, but at the same time Strane tells stories about how he grew up poor and so he frames it as being a similarity between himself and Vanessa. That part of her identity makes her an easier target because she’s isolated and if they were discovered she would be that much easier to dismiss or push aside.

ESQ: It plays into the ‘perfect victim’ myth, was it important to write a victim who was someone someone you might doubt the story of?

KER: It was more just wanting to write her as a complex human being and I think the idea of the perfect victim is at odds with writing a character who is a complex human being. It’s a very narrow definition and doesn’t leave a lot of room for messiness or doubt or inconsistencies. The number one thing that critics point to when trying to undermine a victim’s story is pointing out the inconsistencies, and Vanessa is nothing if not inconsistent.

ESQ: In the same way I felt reading Three Women, hearing someone's abuse story and then seeing them doubted, really lights a fire of outrage in you

ESQ: Absolutely, Maggie’s story in Three Women was incredible, the first time I picked that book up last spring it just threw me because it was so similar to the book I had written. But that’s the case with so many of these stories, they are so similar.

ESQ: What were some of the works that inspired the book?

KER: I was really drawn toward writers like Kathryn Harrison who wrote this incredibly harrowing memoir in the late Nineties about this sexual 'relationship' she had with her estranged father starting when she was twenty. Another memoir I read while working on the novel was Tiger Tiger by Margaux Fragoso, which is an account of how she was groomed from when she was 11. That memoir she really challenged the idea of the perfect victim by showing hers to be complicit, or as complicit as a child can be. Those memoirs were met with intense criticism which I learned a lot from.

ESQ: Why do you think that is? Do you think people can’t get their head around the idea that children might 'encourage' abuse, or that it's more complicated than black and white?

KER: I think comfort has a lot to do with it and not wanting to be confronted with a story that challenges their assumptions. It’s often gendered, this isn’t just a women’s issue because sexual abuse can happen to anyone but it’s often women writers who deal with this subject material who are met with a particular type of criticism, which is rooted in the gendered silencing which has gone on forever.

ESQ: It's obviously a strange time to be releasing a novel, are you hoping it will give people something compulsive and distracting?

KER: I keep hearing from people saying the book has got them out their reading slump or taken their mind off what is going on right now. I have seen some people say ‘this wasn’t necessarily what I wanted to read right now!', but I know when I’m in a gloomy space I don’t want to patronise myself by reading something light.

My Dark Vanessa is out now