Damon Lindelof was 13 years old when, in 1986, his dad gave him the first two issues of a new comic book called Watchmen. It was, Lindelof says now, like nothing he’d ever experienced. Watchmen, by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, shattered all expectations of comic books. It proved that the superhero genre could be as political, controversial, challenging, thought-provoking, and deeply human as any work of dramatic literature. The flawed, flesh-and-blood characters deal with ethical conundrums (who watches the Watchmen?) and anxieties (the threat of nuclear war). “What separates Watchmen from Superman or Batman or even Spider- Man is there’s a depth of psychological pain,” says Lindelof, a TV showrunner with Lost and The Leftovers on his résumé who’s adapting a version of Watchmen for HBO. In setting out to make his own series, he knew he had to do something entirely new—to evoke the feeling he experienced at 13. And that meant not worrying about whether he angered people.

Make no mistake, people will be angry. With its equal critiques of liberals and conservatives, Watchmen is shaping up to be the most controversial TV debut of the fall—and one of the most polarising superhero stories ever told. That’s in keeping with the spirit of the original text, according to Lindelof. “It’s essentially saying we have disdain for people at the centre, because they’re not choosing a side, but we also have disdain for people who are in the extremes, because you can’t live in the extremes. And so let’s just take the piss out of everyone and ourselves in the process,” he says.

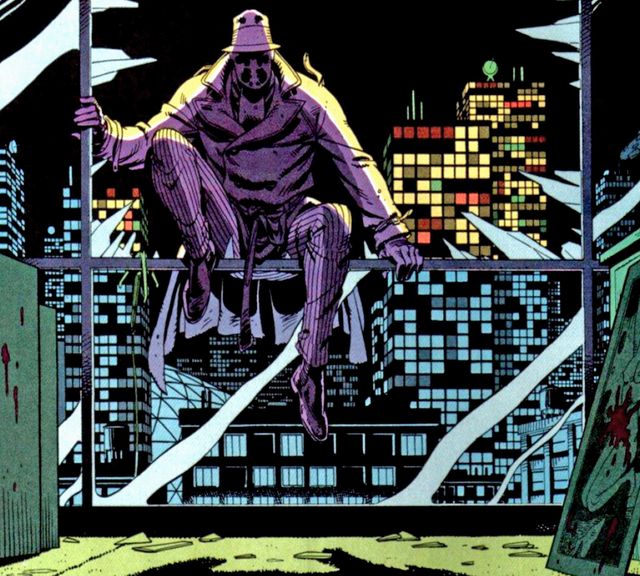

For nearly 35 years, scholars and fans alike have debated the political and social nuances of Watchmen, which partly follows a sociopath with an inkblot mask named Rorschach, who is investigating the murder of a fellow vigilante in a time after masked heroes have been made illegal. Back when Lindelof first read the comic, he considered Rorschach the good guy, but now he believes “good guys and bad guys are not really even part of the vernacular here.” He mentions how in recent months US politicians Ted Cruz and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have each referenced Rorschach to defend points on opposite sides of the political spectrum. “There is a sliver of the Venn diagram where Ted Cruz and AOC basically both have their arms linked in excitement, and that sliver is called Rorschach,” Lindelof says. “You look at him, and you describe what you see in the inkblots. But that’s a reflection of your own personality, or your own psychological profile, or, more specifically, your own trauma.”

In his adaptation—which is not a strict sequel but more of an expansion of the Watchmen universe almost four decades later—Robert Redford has been president for about 20 years and the Supreme Court is stacked with Left-leaning judges. And yet, even in a liberal- controlled country, bigotry remains: A white-supremacist group known as the 7th Kalvary has co-opted the idea of Rorschach. Whereas nuclear war was the root of all evil in the comic, the HBO series positions racism as the greatest evil—one that reaches back many generations before the invention of atomic weapons.

“In order for this to be Watchmen, we have to start with an unsolvable problem, a problem that the most well-intentioned superheroes and vigilantes actually cannot solve,” Lindelof says. “And now we’re in 2019 instead of the ’80s, where it feels like you can’t tell a story about America in any kind of real, historical context that doesn’t talk about race.”

Like the original Watchmen, Lindelof’s interpretation operates with a subversive attitude that says no side is right and there are no simple answers—which isn’t an easy balance to achieve in an era when bothsiderism is a bad word. Lindelof says he does this “very carefully and wildly irresponsibly at the same time. You can’t be afraid to make a mess.” But, he adds, he put together a writers room with people of colour and of differing perspectives who were equipped to dig into a story about race and politics.

The cast is also predominantly people of colour. Oscar-, Golden Globe-, and Emmy-winning actress Regina King stars as the lead masked vigilante, who is—like Rorschach before her—trying to solve a gruesome murder.

This Watchmen series arrives at a time when superhero stories have become the dominant force in the entertainment industry and Disney has essentially unlocked the formula to consistent and unfailable success in its Marvel Cinematic Universe. Lindelof admits that he’s loved the modern Marvel movies, but points out that the Oscar-winning Black Panther pushed the genre into new spaces that it hadn’t explored in a mainstream movie before in terms of telling black stories and having nuanced conversations about race. That, and 2017’s Logan, which followed more of the formula of a Western rather than a comic open up new opportunities to tell stories with nuance and depth that are for adults.

“I imagine that we're going to start to see some really exciting things happening with the form now,” Lindelof says. “Stories like Christopher Nolan’s take on The Dark Knight has already been done. That's not disruptive anymore to just do it dark. So you have to take storytelling risks and reinvent the character.”

This is exactly what Moore did with his original work. But the author is famously not happy with most of the film adaptations of his work. Lindelof says that Moore, “has been very consistent and very specific about not wanting his name to be used to market or sell this project.” At a panel earlier this year, Lindelof said “I’m channeling the spirit of Alan Moore to tell Alan Moore, ‘Fuck you I’m doing it anyway.’” But, during our conversation, Lindelof adds that, “I'm going to honour his wishes, and his wishes were that any communication that would've potentially occurred between he and I would not be shared publicly.” However, Gibbons, who Lindelof calls one of the parents of Watchmen, gives the show his blessing. When they initially pitched it to Gibbons, Lindelof did so with the approach that if “Gibbons says, 'That's stupid, don't do that.' Then we're done. We just take our toys, and we go home. But if he's into it, then maybe we're onto something, because he doesn't have as complicated a relationship with Watchmen as Alan does." In the end, Gibbons approved of their work. “Every single script that we've written has gone to Dave Gibbons. He's a consulting producer on the show,” Lindelof says. “We've had a lot of back and forth, and he seems to think that this thing is worthy of existing.”

While Lindelof maintains that this is a remix of the original source material and not a direct sequel, he does say that we will see some of the original characters—Doctor Manhattan, Laurie Juspeczyk, Daniel Dreiberg, and Adrian Veidt—on screen in some capacity. “We're married to certain things that the canon put out, like Vietnam is a state, or that Robert Redford was running for president against Nixon, or that Adrian Veidt dropped an enormous fake alien being in the middle of Manhattan that killed three million people. That is a 9/11-like event. What does 30 years after something like that happens, what does the world look like?” Lindelof says. “You can’t just do that in passing reference.”

As Lindelof explains, the original 12 comics are treated as canon in his new HBO series. That means the alternate ending of Zack Snyder's 2009 movie never happened—nor did the events of the Doomsday Clock comics, the ongoing DC series that began in 2017 and will conclude with a final issue in December.

"Doomsday Clock is overlapping with the DC Universe and the DC Universe characters, Superman, and Batman," Lindelof says. "So we didn't want to touch that with a 10 foot pole."

Complex sci-fi and fantasy stories are exactly what Lindelof does best. Along with J. J. Abrams and Jeffrey Lieber, he cocreated the groundbreaking ABC drama Lost, which took massive risks for a network television show, with fearless narrative twists. More recently, his three-season HBO drama The Leftovers was a masterpiece of fantastical surrealism—a twisting journey into our collective subconscious (that somehow incorporated the ’80s classic “Take on Me” to perfect effect).

He was deeply influenced by Roots and The Prisoner. “I love that this thing is weird and strange, and it's not self-explanatory, and it feels a bit artsy-fartsy and very counter culture,” Lindelof says of The Prisoner. He also somehow saw Godfather 2 before he saw the first Godfather, which is actually a good comparison to how his new Watchmen series exists. You could technically watch Godfather 2 first, then watch the original as kind of a prequel. The order doesn’t really matter given the context.

“That's a huge part of the calculus in terms of what we were shooting for when we did Watchmen,” Lindelof says. “It was like, ‘Well, maybe you can see our Watchmen before you read the graphic novel, but you might want to go back, you might want to read the graphic novel, because it will give you a deeper and more richer understanding of how all these things are connected, but you don't need to.’”

For now, he knows the backlash to his Watchmen will be inevitable. “I'm sure that it will still be very shocking and very unpleasant when it happens,” he says. “But I also think that there is a possibility that at least some parts of the fandom are going to embrace this thing. I'm hoping for balance.”

He’s “not scared of people calling me a fraud,” he tells me. And, if some people happen to like it, he’ll be happy.

“I don’t want to be an imitator,” he says of Watchmen. “I don’t want it to feel like it’s some simulacrum of Watchmen. I want it to feel like it’s pulsing with that same kind of energy that made the original work. That’s the sweet spot.”

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox.

Matt Miller is a Brooklyn-based culture/lifestyle writer and music critic whose work has appeared in Esquire, Forbes, The Denver Post, and documentaries.