It was Piers Morgan who called first. It had just been announced that I would be leaving a job I had successfully done for 22 years, and Piers was on the phone offering his advice.

“Mate,” he said, as his virtual arm reached out across my shoulders.

“I’ve only got one word of advice for you, and it’s this: wait. Trust me, I’ve been in this situation a lot, and I’ve always found it’s best not to make any rash decisions, not to rush back into the fray, to take a step back and take a good hard look at the situation. And wait.”

Which is precisely what I did. Piers’ paternal thoughts (he is much, much older than me) were actually exactly the same as mine, and waiting is what I had already decided to do.

First, I went on a very long family holiday to somewhere lush and expensive on the other side of the world. Then when we eventually came back, we did it again. Just to make sure that we liked it.

We did. I certainly did. I’d worked bloody hard for over two decades at this particular job, really hard, and I deserved the break. A rest certainly did feel like a change.

Then, when we finally returned to what turned out to be another lockdown, the phone rang. Would I be interested in writing 5,000 words about so-and-so? Wow, an old-fashioned piece of journalism? Would I? Yes, actually, I think I would. Thank you very much.

A few weeks later, some consultancy appeared: I’m helping a household name turn themselves into a media brand. In the autumn I made half a dozen programmes for the BBC, and I have another half a dozen scheduled for the end of the year. And then, when I figured I probably had enough on my Alan Partridge-sized plate, I was commissioned to write another book; so I’ve spent the last six months asking dozens of people what it was like working with — and sleeping with — Andy Warhol.

And then I was paid a visit by an old friend of mine (he’s even older than Piers), Guy, a long-serving musician who had a suggestion that he thought I might find interesting. Which made me immediately intrigued. Guy is one our most successful songwriters. He has written classics for Elvis Presley, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Cliff Richard, the Hollies and Frankie Valli, to name a mere smattering. His suggestion was certainly a strange one: Would I like to write a musical?

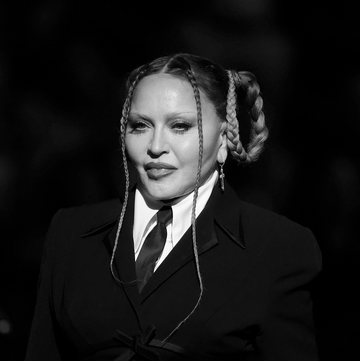

Guy’s idea was to produce a musical based on the work and life of the great American tunesmith, Jimmy Webb [picture above, in 1975], the man whose “Wichita Lineman” was once called the greatest song ever written by no less a personage than Bob Dylan. Webb is one of the most accomplished songwriters in the world, responsible for “MacArthur Park”, “By the Time I Get to Phoenix”, “Up, Up and Away”, “Didn’t We”, “All I Know”, “Galveston”, “Still Within the Sound of My Voice” and hundreds of others. Both Guy and Jimmy wanted me to write the book (the show’s story), and was this the kind of thing that might interested me?

Having established that I had absolutely no expertise in this, nor indeed any experience, both Guy and Jimmy were adamant that I was the person for the job; I had previously written an ode to “Wichita Lineman” for Faber, and it was obviously this that had made them think I might be appropriate.

Having thought about the idea for longer than I might have done (I reckon it took me three minutes), I dived right in. Well, Guy and I did. We have been meeting once a week for the last three months to try and wrestle down a first draft of the show, and I have to say I have rarely been more energised about a project. I compare it a bit to building a house, something else I have no experience or expertise in. You find your land, you design where you want everything to go, you build the foundations, and then tinker and tinker until you ended up with hopefully the thing you want. Wearing hard hats the whole time, of course.

The process is ostensibly quite simple. Guy comes to my house, and we sit opposite each other at my large kitchen table. It’s not Putinesque, but it’s big enough for a heated exchange if we disagree about something. Then I make tea and we drink it (biscuits tend not to appear until the afternoon). Then we start. What songs do we need to include? What songs do we want to include? Are the ones we chose last week really the ones that are going to work? How many characters should we have, apart from the ones we absolutely need, including Jimmy himself, his mother, father, lovers, colleagues, etc. Where is all this set, in how many places, and how do we get one from one place to another? How do you — we! — develop character, and how do you — we! — move things along without resorting to exposition?

Working with Guy has been something of a dream, because he is a stickler for the truth and, whenever I start on another flight of fancy, suggesting that we conflate events, or alter the chronology of Jimmy’s story, he’ll look carefully down his nose, gently cross his arms and say, “No, I really don’t think we want to do that, do we, Dylan?”

And he’s usually right. Although not always, which is why this is a genuine collaboration. (I know where the biscuit tin is hidden, so he has to cut me some slack occasionally.)

The most unnerving part of the process for me has been putting words into people’s mouths, creating narration and dialogue for people and events that occurred over 50 years ago, in places long since forgotten, even by those who were there. How should we use character to drive narrative, and how do we airdrop this person into a situation when they might not have actually been there? (It’s simple, Guy would say: we don’t.)

We have worked hard, extremely hard, and have now finished our first draft. It’s pretty good, we think, although we might just be pleased because we’ve developed something that actually feels like a musical. Whether or not it’s good enough to attract a promoter, a theatre and an audience is another thing altogether. In fact, it’s several things. Indeed, I keep saying that there are a thousand ways to fail before we get anywhere close to an opening night. But then that’s sort of the point, I guess, managing the trajectory of this great leap into the unknown, holding hands, closing our eyes and hoping for a soft landing.

All I’ve got to do now is find a part for Piers Morgan.

Dylan Jones' latest book, Faster Than a Cannonball, is out on 11 October. This piece appears in the Autumn 2022 issue of Esquire, out now