Didn’t get your fill of nuclear bomb origin stories last year? Well have no fear, as fresh from his (objectively quite funny) cameo in Oppenheimer, Albert Einstein is now taking centre stage for his own version of events. Just like with Oppy's Oscar-nominated biopic, it will explore the late physicist's own conflicted emotions around the fateful scientific discovery.

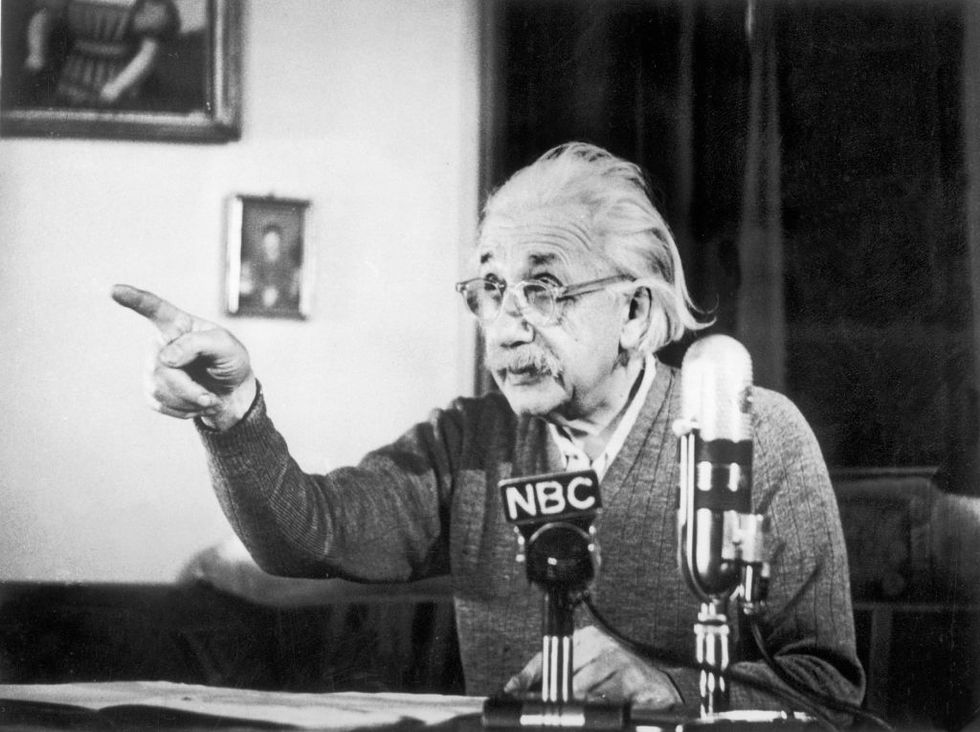

Einstein And The Bomb is that odd thing, a docudrama: real world footage spliced with rather hammy dramatisations of the German theoretical physicist that, according to the official synopsis, will follow “what happened to Einstein after he fled Nazi Germany […] using archival footage and his own words, it will dive into the mind of the tortured genius.”

In the trailer, he says: “Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in producing an atomic bomb, I would not have taken part in opening that Pandora’s box.” But what was Einstein’s actual involvement in this particular part of history? And was it really the case that a pivotal moment take place in a wooden cabin in Norfolk?

The backstory

By May 1933, 54-year-old Albert Einstein, despite now being recognised as one of the greatest scientists in human history, was a wanted man.

As a Jewish man in Nazi Germany, a brochure was published entitled ‘Jews Are Watching You’. It accused Einstein of producing “lying atrocity propaganda against Adolf Hitler”. Under his picture it said: “Not yet hanged.”

By September of the same year, his house in Berlin was burgled and a reward of £1,000 was offered for his murder, so the next day he fled with his wife, Elsa, and they never returned to continental Europe again.

Instead, Einstein headed to a secluded hut in Roughton Heath, Norfolk, where he stayed for three weeks and gave several press interviews. His recent experiences led the great thinker to come to an historic conclusion, according to the screenwriter for the film, Philip Ralph.

“Prior to that point, Einstein had been an avowed, passionate advocate for non-violence and pacifism," he told The Guardian. "But at the end of that three weeks, he gave a speech to 10,000 people at the Royal Albert Hall where he effectively said there is an existential threat to European civilisation, and we will have to fight it.”

The bomb

Two days after Einstein’s speech at the Royal Albert Hall, he left the UK and headed to Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton University, which is where he first met Oppenheimer. The pair weren’t especially close at this point in time, as Oppenheimer wrote in the New York Times in 1966: “Though I knew Einstein for two or three decades, it was only in the last decade of his life that we were close colleagues and something of friends.”

But it was Einstein’s most famous discovery in 1905, E equals mc², which led to the concept that atomic energy would someday be unlocked. In the wrong hands, it could be catastrophic.

In 1933, the Hungarian-German physicist, Leo Szilard, who had previously worked with Einstein, discovered the concept of the nuclear chain reaction. But five years later, when scientists in Germany split the uranium atom, Szilard began to sound the alarm with his colleagues, and warned Einstein about the problem in 1938.

By August 1939, a month before the outbreak of war in Europe and plagued by fear that the Nazis would develop the weapon first, Einstein wrote to President Franklin Roosevelt – in a letter drafted by Szilard – about the need to accelerate the US development of a nuclear bomb.

As per The Atlantic, Einstein wrote: “The release of atomic energy has not created a new problem. It has merely made more urgent the necessity of solving an existing one... As long as there are sovereign nations possessing great power, war is inevitable. That statement is not an attempt to say when war will come, but only that it is sure to come. That fact was true before the atomic bomb was made. What has been changed is the destructiveness of war.

“I do not believe that civilization will be wiped out in a war fought with the atomic bomb. Perhaps two thirds of the people of the earth might be killed, but enough men capable of thinking, and enough books, would be left to start again, and civilization could be restored.”

As a result, Roosevelt set up a project with scientists working on chain reactions using uranium, which could then be developed into atomic bombs.

Two months after Einstein’s letter, Roosevelt told him he would be setting up a committee of civilian and military representatives to study uranium, which later evolved into the Manhattan Project. Einstein wrote further letters to Roosevelt, recommending further steps to take in the development of nuclear warfare.

While Einstein was never involved in the Manhattan Project, led by Oppenheimer – in 1940, the U.S. Army Intelligence office denied Einstein the security clearance needed to work on the Manhattan Project, as he was deemed a “potential security risk” – when the first bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6 1945, Einstein is quoted as having said: “Woe is me.”

Einstein clearly had regrets about his involvement in the creation of nuclear weapons. He was quoted repeatedly saying: “I do not consider myself the father of the release of atomic energy”. In an interview with Newsweek magazine, he said that “had I known that the Germans would not succeed in developing an atomic bomb, I would have done nothing.”

And in 1954, a year before he died, he wrote in a letter to his friend, the chemist Linus Pauling: “I made one great mistake in my life - when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending that atomic bombs be made.”

Einstein died aged 76 in 1955 after a blood vessel burst near his heart. His reported last words? “I am at the mercy of fate and have no control over it.”

Einstein And The Bomb streams on Netflix from February 16.