There was perhaps nothing Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán Loera wanted more than to control his legacy. When he stood trial in November, 2018 in Brooklyn, far from home, the narrative was less his than it ever had been. Noah Hurowitz covered that trial for Rolling Stone, and continued his reporting in a new book "El Chapo: The Untold Story of the World's Most Infamous Drug Lord", excerpted here.

El Chapo wanted to make a movie.

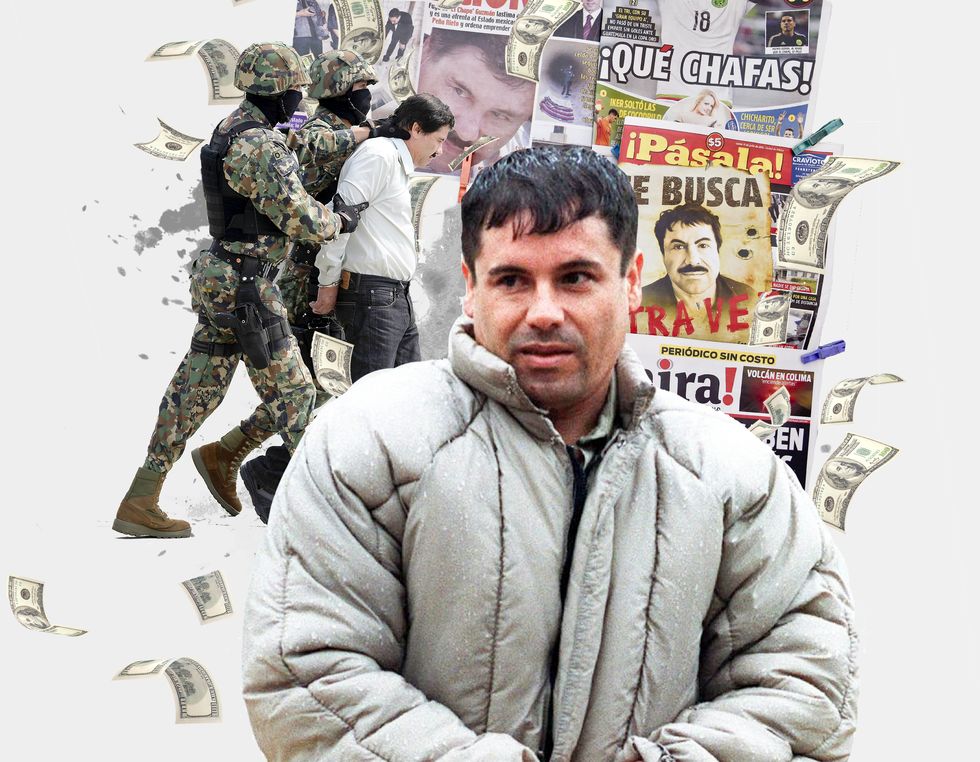

Picture this: The most wanted man in Mexico has clawed his way back to power after escaping from what was supposed to be the most secure prison in the country. He has rebuilt his empire, and is moving more coke, weed, heroin, and meth into the United States than ever before. Then, after being captured again, he escapes—again! He’s back in the mountains, no prison can hold him! His name is synonymous with drug trafficking. He’s the most famous capo in a generation, having risen from a crowded field of fellow smugglers to be the most recognisable brand-name drug lord since Pablo Escobar. He’s outlived most of his enemies, only to see them replaced by new enemies.

As Joaquín Guzmán Loera consolidated his position in the decade following his escape and his nickname, El Chapo, became known far and wide, he was never the only kingpin in town, nor even the most powerful; he was just one powerful leader in a federation of several powerful leaders. The Beltrán Leyvas, his allies-turned-enemies, had more friends in high places, and more sway with local proxies in areas outside of Sinaloa; his longtime partner Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada had probably wielded more power at home in Sinaloa—albeit behind the scenes. But El Chapo, with his prison break and his decade-plus track record of making fools of the cops and soldiers and gringos chasing him, was the lightning rod, the face of it all.

North of the border, rappers like Gucci Mane and 2 Chainz pay homage to El Chapo, and in Mexico, folk troubadours like Los Canelos de Durango pen folk ballads known as narcocorridos in El Chapo’s honor, belting out his exploits over the clamour of guitar and accordion.

But El Chapo wanted a movie. Ballads were one thing, but the narrative was out of his hands, and other people were profiting off his hard work, his well-earned fame. Books, television shows, songs, all making money for other people. Already basking in an infamy that eclipsed his real-world power and wealth, El Chapo had held multiple meetings over the years with producers and movie stars in a bid to put himself on-screen.

The idea for a movie about El Chapo first came to the wife of Alex Cifuentes, El Chapo’s Colombian hostage-turned-lieutenant, in early 2008, shortly after Cifuentes went to join El Chapo in the mountains as human collateral.

“She recommended to Señor Joaquín that he do that because he was always on the news and in the newspapers and everywhere,” Cifuentes recalled later. “So she said he should do a movie about his life so he could make the money because the money was being made by all the papers.”

In the world of Mexican narcos, this wasn’t that unusual: The movie industry in Mexico is awash with low-budget, direct-to-DVD action films, so-called narcopelículas glorifying the lifestyles and exploits of drug traffickers, some of them absurd fever-dream villains, others thinly fictionalised. Generally speaking, these are not the best movies. Still, they sell, and one can find innumerable narcopelícula DVDs sold at markets across Mexico. They are sometimes financed with drug money from narcos looking to launder a bit of cash and make a cool movie in the process, or by prominent criminals hoping to put out an idealised depiction of their life’s work. In the wake of the 2009 arrest of Edgar Villarreal, the American-born Beltrán Leyva ally known as La Barbie, the captured narco told police he had forked over $200,000 to a movie producer for a film about his life, although he never followed through to make the movie.

When Cifuentes brought the movie idea to El Chapo, he loved it, and they hatched a plan: With the help of a ghostwriter, El Chapo would draft his life story, while Cifuentes would find a producer to turn the manuscript into a movie. With the help of one of his men in Colombia, Cifuentes eventually settled on a Colombian producer named Javier Rey, a onetime documentarian who shifted from making films about human rights issues in the 1980s to making feature films in the mid-2000s, including the 2007 joint Mexican-Colombian production Polvo de Ángel (Angel Dust).

A few months after Cifuente’s wife first suggested making a movie, Rey journeyed to Sinaloa and flew out to one of El Chapo’s mountain hide-outs in order to interview the kingpin. Over a series of interview sessions, El Chapo held forth on his life, regaling the producer with epic tales of his life and work, his escape from Puente Grande, confrontations with enemies, even an incident in which he claimed to have been detained by soldiers and hung upside down by a helicopter. To underscore his claim that the troops had tortured him, El Chapo showed the producer his hands, which he said bore the marks of the rifle butts the soldiers had used to smash his fingers. (Cifuentes, though, did not recall seeing any visible scars.)

To facilitate the project, El Chapo instructed various relatives to sit down with Rey and give the producer additional info on his life. Out of these efforts emerged a manuscript, a biography of sorts with the working title “El Señor de la Montaña,” or “The Lord of the Mountain,” according to one law enforcement agent who has seen the manuscript. A copy was sent to one of El Chapo’s lawyers, and another is sitting somewhere on an FBI server, given to the agents a few years later by an informant.

Over the next several years, the movie project inched along, even as El Chapo steadily became bogged down in fratricidal wars with former allies. He met with Rey once more in 2012, but this time it didn’t go so well; at a final meeting in Mexico, Rey told Cifuentes that he was looking to receive 35 percent of any profits from the book and movie.

When El Chapo heard that, he exploded. He had been planning to give the producer a much smaller lump sum, but now this request, which he perceived as abject greed on Rey’s part, got him thinking about this stranger to whom he had opened up, had told about his life, introduced to his wives and children. Brooding about Rey’s perceived treachery, El Chapo became convinced that the producer was an informant who had come to collect information and give it to the authorities to help capture him and build a case against him. El Chapo decided the producer had to die, and told Cifuentes to make sure it happened.

Cifuentes began plotting to have one of his men in Colombia murder Rey, just as he had attempted (however sloppily or half-heartedly) to locate Christian Rodriguez. Before he could put the plan in motion, however, Cifuentes was arrested outside of Culiacán in 2013, and from jail sent word to his wife telling her to warn the producer of the danger he was in. Not much is known of how the situation resolved itself beyond the dry language of court documents, in which prosecutors note that “the Colombian producer has survived.”

But El Chapo never lost his interest in making a movie. It seems his infamous meeting with Kate del Castillo and Sean Penn—of which the world learned only after his final arrest in January of 2016—was done in the interest of getting a movie made, and his lawyers even reached out to a New Yorker writer to see if he’d like to help with such a project. In the end, though, it was El Chapo’s criminal trial that delivered the dramatic showcase that he had long sought. But yet again, the narrative wasn’t his to control.

Beginning in November 2018 in the federal courthouse of the Eastern District of New York in downtown Brooklyn, the trial was a three-month slideshow of greatest hits, featuring an all-star cast from El Chapo’s past, including the cartoonishly disfigured mass murderer, Chupeta; Lucero, the tearful ex-lover; Miguel Ángel Martínez Martínez, the former cocaine addict and onetime close friend harbouring a twenty-year-old grudge against the defendant; Dámaso López, the treacherous lieutenant who still swore love and loyalty; Christian Rodriguez, the young outsider whom El Chapo had trusted with his life and who in the end helped tie the whole case together.

But what was the point of it all? For prosecutors, and the government they served, the point of this case was clear: Putting El Chapo away sent an “unmistakable message.” What that message was depends on who you talk to. According to the Justice Department, the message was that no drug lord was untouchable. To El Chapo’s defense team, the message was that El Chapo was stitched up, doomed from the start. To many Mexicans, dismayed at the lack of testimony about actual crimes in Mexico, the message was that selling drugs to willing buyers in the States is worse than murdering tens of thousands of people in Mexico. With some exceptions, such as the discussion of the bribery allegations against Genaro García Luna and Enrique Peña Nieto (which both deny), prosecutors were largely successful in keeping the proceedings laser focused on the testimony against El Chapo and in barring any discussion of anything that would cause embarrassment to unnamed “individuals and entities” not directly tied to the El Chapo case.

As if to underscore the folly of the whole affair, news broke the same week that jury deliberations began that officials in Arizona had made the largest-ever seizure of fentanyl along the border. Days before the verdict arrived, the DEA announced the seizure of fifty pounds of fentanyl in Chicago (destined for the Bronx). El Chapo was newly convicted, but he’d already been in the United States for more than two years. Any notion that his absence from Mexico would put a dent in the drug trade was a fantasy.

On July 17, 2019, months after being found guilty, El Chapo appeared in public for the last time to hear his sentence, and to make one final statement to the public. Apart from a few quiet yes-and-no answers during the trial, it was the first time he’d spoken publicly since appearing on video for Sean Penn back in 2015. As the trial wound down, there had been great speculation as to whether El Chapo would take the stand, and some disappointment when he had sensibly chosen not to. Now was the chance, however, to hear his last words.

Standing up at the defence table, El Chapo greeted Judge Brian M. Cogan and launched into a muted diatribe against his treatment in the United States.

“They say they are sending me to a prison where my name will never be heard again,” El Chapo said, pausing for his translator to repeat in English. “I take this opportunity to say there was no justice here.”

Stumbling a bit as he read his prepared remarks, he cataloged the indignities he had faced during his incarceration in Manhattan.

“I have been forced to drink unsanitary water, denied access to air and sunlight,” he said. “It has been psychological, emotional, mental torture twenty-four hours a day.”

Up next was Gina Parlovecchio, one of the lead prosecutors, who lambasted El Chapo for his apparent lack of remorse.

“Throughout his criminal career, this defendant has not shown one shred of remorse for his crimes,” Parlovecchio said. “You heard that again today.”

The final word came from Andrea Fernández Velez, the former assistant to Cifuentes turned FBI informant who had escaped a contract on her life, apparently the only person willing to read a so-called victim impact statement at the hearing. Breaking down in tears several times as she read her own prepared remarks in Spanish, Andrea apologised for her mistakes, and laid out the psychological toll she had suffered when she realised that the people she had worked with so closely wanted her dead.

“When we started to develop the movie project, I came to view him as a good person, with great kindness and charisma,” she said. “When I saw the reality and wanted to distance myself, my friends turned out to be . . . captors.

“When I tried to leave the organisation, I was told I could only do it one way: in a plastic bag, feet first,” she continued, as El Chapo ignored the scene completely and turned to blow a kiss to his wife. “I lost my family, my friends. . . . I became a shadow without a name. I had everything, I lost everything, even my identity.”

Then she turned away from the man who had wanted her dead, and walked through a side door toward the rest of her life, looking back over her shoulder just once.

Finally, with Andrea gone, it was time for the sentencing, although due to federal guidelines and the charges of which El Chapo had been found guilty, it was always a foregone conclusion. After so much anticipation, it was almost anticlimactic to hear the judge read out the sentence: life in prison plus thirty years.

In the final moments of the spectacle of El Chapo, the ending he never would have written for himself, the Lord of the Mountains turned around, craning his neck for one last glimpse at his wife. It was likely to be the last time he would ever lay eyes on her.

He gave her a thumbs- up, smiled, and turned his head to walk toward his grim fate. The marshals led him through the door and he disappeared forever into the black hole of the United States federal prison system.

His final act is playing out now, in a tiny cell in ADX Florence, a supermax prison on the windswept high desert plains of Colorado.

In Mexico, the story goes on without him.

From EL CHAPO by Noah Hurowitz. Copyright © 2021 by Noah Hurowitz. Reprinted by permission of Atria Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Noah Hurowitz is a journalist based in New York City. He covered the trial of El Chapo for Rolling Stone, and his work has also appeared in the Columbia Journalism Review, the Village Voice, The Baffler, New York magazine, DNAinfo, and many more. El Chapo is his first book.