If only my friends talked about me behind my back the way Mahershala Ali’s peers and friends talk about him. I contacted some of his colleagues from his recent career — one any actor would kill for right now. Like Barry Jenkins, the director of Moonlight, for which Ali won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. And Peter Farrelly and Viggo Mortensen, who worked with Ali on his next film, Green Book, another diamond of a movie. And then Stephen Dorff and Nic Pizzolatto, with whom Ali made True Detective season three and which casts all memories of the underloved season two to the winds. (Ali calls it “the most fulfilling thing I’ve done to this point.”)

This is what they say, to a man: that Ali is respectful, kind, elegant, a gentleman, humble, disciplined and unreasonably talented. The biggest word in the Word Cloud, however, is “sincere”. He speaks the truth and he means it. You’ll see, they tell me, everyone does.

So I’ve come to Zinc Cafe & Market today, a trendy vegetarian spot in the Arts District of Downtown Los Angeles, wondering already how I can be more like him. I’m here to take notes. Even though I’m yet to meet the guy, to paraphrase Jack Nicholson in As Good as it Gets, he makes me want to be a better man.

Here he comes now, slim and long, with black jeans and Converse, a loud shirt and a little black beanie. He doesn’t just shake my hand, he clasps and bows, or maybe that’s just because I’m so much shorter. He’s all smiles and manners. Where would I like to sit? Where’s “Sanjiv” from, is that Indian? How long have I been in the States? It turns out he’s practically a neighbour; he just bought a place in Mount Washington, a quiet neighbourhood in north-east LA, where he lives with his wife Amatus, an actress and musician, and their two-year-old daughter. At a local street party recently, he went around smiling, with a little badge saying how long he’d lived there (one year).

“Do you know that coffee shop Habitat?” he says. And I do. “I just love the north-east because it reminds me of the Bay Area [where he grew up]. West LA is more flashy or commercial. But the mentality here is more quality over quantity. It values work. It’s humble.”

I’m nodding vigorously. At risk of whiplash. We’ve found a shady corner table, ordered coffees, and landed on the mushroom burgers, yes they look nice, two of those please. And already I’m thinking what an agreeable and kindred spirit Ali is, such a happy and gentle soul, and what a pleasant lunch this is going to be.

You’ve seen him before, of course you have. If not in the The Curious Case of Benjamin Button over a decade ago, then possibly The Hunger Games, or as the sleek lobbyist Remy Danton in House of Cards. He was Juan, the drug dealer/father figure in Moonlight, which netted him that Oscar even though he was only in the first third of the movie. And he’s about to become a lot more visible — no Oscar curse here. Ali’s next two projects have been perfectly chosen: actorly and serious, high profile and relevant. This year stands to be even bigger than the last.

In Green Book, he plays the late classical pianist Don Shirley who went on a tour of the Jim Crow Deep South in the Sixties. An aloof and ascetic character, he’s paired with a loudmouth driver from the Bronx, a goombah played with comic brio by Viggo Mortensen. It’s an odd couple road trip that grapples with issues of race, class and sexuality, but with a lightness of touch, thanks to — who’d have thought — the director of Dumb and Dumber.

Since its release, the Shirley family has complained about the way Don was written, and Ali has called to apologise — “a very, very respectful phone call”, according to Shirley’s next of kin. But it’s hardly Ali’s fault. He played the guy in the script, and he did so brilliantly.

“You usually see a lot of the actor’s personality in the person he’s playing,” says Farrelly. “But Mahershala is nothing like Don Shirley. He disappears into character, it’s fascinating. His body language, posture, voice, everything.”

Mortensen’s transformation was widely praised, partly because he put on so much weight — critics love it when an actor fattens up. But Ali’s change is no less dramatic. He went from a hardcase dealer in Moonlight to the high cultured Shirley, 25lbs lighter, and a model of elegance and refinement. From a Sharpie to a quill. “I met him [before filming] at an industry brunch thing,” Mortensen says, “so when I saw him as Don Shirley, I could see the difference. He seemed taller and more delicate. Small and discreet in every way. The way he grasped objects, the way he gestured.”

Ali spent three months learning piano, even though Peter Farrelly assured him he’d never be good enough. “I said, ‘Mahershala give it up!’ And he said, ‘Pete, when I sit at that piano, I want other piano players to say, “Oh that guy plays the piano.” Just like I can tell if someone’s a dancer on the subway by the way they walk.’ And you know what? He learned to play for 10 seconds, enough to get us off to the races.”

The chemistry between Mortensen and Ali is at the heart of the movie’s charm. And they’re very similar as actors, by all accounts. Both of them meticulous and finicky, according to Farrelly, and generous in spirit. “Mahershala doesn’t just pay attention to his performance, he’s doing everything he can to help me as well,” Mortensen says. Barry Jenkins calls him “selfless.”

But beyond that, both Mortensen and Ali view acting as an aid to living, a school of life. “It’s about understanding different points of view and not judging,” Mortensen says. “That’s how you play a character in a respectful way.” Ali goes further. “For me, the arts — writing, and later on acting — became a place where I could speak to feelings and ideas I couldn’t articulate in my everyday life. It became this ongoing experiment to understand the psychology behind my characters’ choices. I’m fairly empathetic but acting has definitely expanded that, and along the way, this work has helped to give me a real peace. Putting my energies towards someone else helps me process my own stuff easier.”

He didn’t feel this way when he started out, though. Back then he was just a kid looking for attention. He grew up in the blue collar town of Hayward, outside Oakland, Northern California, the only child of two teenagers. His mother, who was 16, came from a staunch religious family, and his father, who was 17, wanted to dance on Broadway. Faith on one side, the arts on the other. Perhaps inevitably, they split when he was three; Ali recalls his mother leaning on the dresser and crying, “He’s gone, your father’s gone.”

Soon afterwards, Ali was at his father’s apartment, watching him win first prize in the dancing competition on Soul Train, one of the biggest shows on TV at the time. With the $2,500 prize money, his father moved to New York to dance on Broadway, and from then on, a sense of melancholy entered Ali’s life. He went from a quiet toddler to a loner at school — “never quite in the tribe.” Eventually, he learned to love solitude. “I’ve always been quite reflective.”

He lived with his mother, who cut hair for a living, while his aunties raised him with his maternal grandmother, and then later on, a very tall and strict stepfather. But throughout his childhood, he would visit his biological father on the East Coast, or wherever he might be on tour. “We went to museums, and theatres, and I saw all kinds of indie films and art shows. I knew there was another world out there,” Ali says.

At 16, he moved in with his grandparents on his father’s side. They were older, and more stable, and helped put Ali on a path: to win a basketball scholarship to St Mary’s College of California near Oakland, which he did easily. Barely a year in, he soured on pursuing it as a career. “I found college sports exploitative,” he says. “They saw players as a product. We were just there to win championships. So I used sports to pay for my education. I knew I had to do something creative like my dad.”

He was scarcely a year into acting at St Mary’s, however, just dabbling with the idea it might be worth pursuing, when tragedy struck, the defining tragedy of his life. His father died, suddenly. Ali was 20. As hard as it was, the loss gave him the kind of clarity only mortality can — that he would follow in his father’s footsteps to New York and become an artist himself, albeit an actor, not a dancer: “I saw how short life can be, and that you have to go for whatever it is you want in life.”

He made it onto the graduate programme at New York University and within a year had moved to the city to emulate the father who’d inspired him, but was not alive to see it. Such a poignant position at such a young age. Even now when he bumps into actors his father used to know, they double take, sometimes bursting into tears. “It’s not just that I look similar, it’s because they knew my father’s experience, how he struggled,” he says. “And now they see me where I’m at and they know it’s connected.”

As though his life hadn’t changed radically enough in his twenties — with his father’s death and his move to New York to act — Ali converted to Islam in his last year of graduate school. On 31 December 1999, for that matter, right on the cusp of the new millennium. It was a lightning bolt, is how he explains it. He’d visited a mosque as part of his spiritual seeking — like his father, he was carving his own spiritual path — and as he recited the prayer, an Arabic prayer he didn’t even understand, he found himself in tears. “I had no reason to cry, I wasn’t going through anything at that time,” he says. “Things were pretty good actually. But the prayer was like resonating in my body.”

So he went from Gilmore to Ali, and started praying five times a day. And it suited him. He liked the idea that God was God and man was man. “I never understood why they talk so much about Jesus in the church; what about God the Father?” And he liked the discipline, what he calls, “the regimented qualities of Islam. I need structure to be fulfilled and happy. If I’m free to do whatever I want, that’s not going to go well.”

In the Venn diagram of Hollywood actors and devout Muslims, the circles make only glancing contact. Ali is one of only half a dozen at that nexus. But it’s the only life he’s known. He was never a working actor before his conversion, and he’s never done any other job as a Muslim. Just as with his childhood — between his Christian mother and his dancer

father — his career was also forged between faith and the arts, two loyalties that are often in conflict, as he soon discovered.

While still at graduate school, Ali was due to play the part of Achilles in Sir Peter Hall’s production of Troilus and Cressida. But when a colleague congratulated him, saying, “You’re playing a god!” Ali quit on the spot. “I can’t do that, there’s no god but God!” Then he moved to LA and was booked at his very first audition: as a regular on Jessica Alba’s show, Dark Angel — a peach of a job for a fledgling actor. “But then I found out it was about these demons and gods and… same thing. Can’t do it.”

His agents were going nuts, of course. Most actors have to wait tables for years before getting breaks like these, and here was Ali nailing audition after audition and then turning them down for religious reasons?

“I’ve mellowed out since,” he says grinning. “Now I think that for the purposes of art, I can play those roles as human beings, not gods. I can also differentiate between what I believe, and what the story’s saying. But at the time, I was new, just figuring it out. I had no one to have that conversation with.”

He might be able to play humanoid god characters now, but sex scenes are still off limits. Ali was always strict when it came to girls. As a boy, his mum forbade him from dating. “Sure, super-frustrating at the time, but I appreciate it now. I would rather that than be totally free and have my whole trajectory be affected.”

Like your parents?

“Exactly.”

When he was offered a part on The Curious Case of Benjamin Button — another plum gig — he asked the director, David Fincher, if he would not shoot the scripted sex scene he had with Taraji P Henson. Fincher obliged. “They just show us dropping down into a kiss and then disappearing. It’s not simulated sex.”

But not everything went so smoothly. More recently he was up for a part in The Deuce, the HBO series by David Simon (The Wire), set in the sleazy underbelly of New York in the Seventies. “I asked them, ‘Do you guys foresee my character needing to have sex and show it?’ And they did. So, you know, I had to pass!” He laughs. “There were a lot of those.”

Ali had been working pretty steadily for a decade or so, building up his credits — even releasing a rap album in 2007 under the name Prince Ali — when suddenly, it all fell apart. His grandfather had a stroke, and for a year-and-a-half, Ali moved to Las Vegas to care for him. By the time his grandfather died, Ali was broke and the industry was floundering. A writers’ strike was underway and an actors’ strike was pending.

“I moved back to LA, but I could barely afford to rent a room in this small house,” he says. “It was tough. I remember finishing pilot season and thinking, ‘I don’t know what happens now. I got nowhere else to turn.’”

He’d learned from his father that acting was a blue-collar hustle and a hard business in many ways, with all its peaks and troughs, the way it tested your faith. He was now 37 and struggling financially — many of us might have wavered. But Ali had never been in this for the money. Some 15 years earlier, just as he was beginning to think of himself as an actor, he’d attended a Shakespeare summer camp and the camp leader told the group in no uncertain terms that if they wanted to get rich and famous, they should leave. Acting was about the work, not the rewards. It made an impression on Ali, who took that lesson to heart with the same purpose he brought to his religious practice. “It took time but I learned that acting was about just being of service to stories and characters. And I always believed that if I just did my best work, it would naturally expand.”

Sure enough, the phone rang. It was an old casting agent friend who had no idea of Ali’s predicament, she just thought he’d be good for this new show on Netflix about politics. “I was like, ‘Netflix?’” Ali says. “Back then, that was like Blockbuster making TV. But House of Cards changed the game. I was lucky.”

It’s luck if it happens once. But twice, you have to wonder. Moonlight captured the public imagination just like House of Cards had — call it Exhibit B in the case against trying to be rich and famous. Ali was doing great at the time. Netflix had cast him in Marvel’s Luke Cage, his star was rising, and he wasn’t short of movie opportunities. But instead of a bigger movie, with named actors and directors, he opted for a low-budget, passion project by a virtually untested director who had cast a string of non-actors to key roles (Ali was the film’s only professional actor). Why? Because Ali had seen a short film, Medicine for Melancholy, by this director back in San Francisco: just a couple of people walking and talking through the city — the budget was all of $12,000. He liked it. And the script this director had sent him made him cry. That was all he needed.

“It was incredible,” says Barry Jenkins. “He said, ‘I’m such fan of your first film that nobody has seen, that whatever you need me to do, I’ll come to Miami and do it.’ When you put that kind of energy into the world, amazing things happen. And they did. I’m so happy for him.”

One of the main perks of winning an Oscar is the clout it carries, especially in the first year, when it’s at its shiniest. When Ali was offered True Detective, he was immediately interested. The series was returning to the winning formula of its first season, back to Southern Gothic, with the dark forces and old religion, where children go missing and hope for humanity looks ready to curl up and die. But in the script, Ali saw the black cop was the second lead. He wanted it to be the first; a character we’d see at 35, 45 and 70 years of age, something never tried on television before.

“If I could articulate the type of challenge that I wanted, whether for film or TV, it was Wayne Hays,” he says. “It’s just a massive role. Expansive. It checks so many boxes for me as an actor, that in terms of TV, it doesn’t get better. I just thought, coming off the Oscars, if I didn’t get that opportunity then, I don’t know how you get to that place.”

He made the case to the show’s creator Nic Pizzolatto. A black lead, he argued, would heighten the complexity and tension, as the detectives tried to solve a murder in Eighties’ Arkansas. He sent pictures of his grandfather on his mother’s side, who’d been a state police officer in California in the Sixties, “just to show him how personal it was for me.” And Pizzolatto agreed.

“I just listened to him...” the screenwriter says. “He said often black actors get roles that are largely defined by race, and this was an opportunity for a more wholly developed character. I thought I’d be incredibly fortunate to have this actor to build the show around.” So he went back and rewrote the script with Ali in mind.

Ali had no time to prepare. There was a week between the Green Book shoot wrapping-up and True Detective starting — which makes his performance especially remarkable. They shot in Fayetteville, Arkansas, over 18-hour days (four spent in make-up each morning). It took stamina, focus, everything he had. But the result is something special. “I’ve never seen an actor do what he does here,” Pizzolatto says. “For each iteration of this character there’s such subtle emotional and physical differences that the evolution is both evident and utterly believable. His work as a 70-year-old is one of the greatest performances I’ve ever witnessed.”

He’s not the only one to gush. Stephen Dorff, Ali’s co-star, tells me this shoot took everyone to their limits. “There’s this one scene,” he says, “I think it’s in episode five. It lasts like nine minutes. And we were so in it, man. At the end, we just grabbed each other, and Nic came in, and we all had this emotional hug after the cameras had stopped rolling. Everyone just hugging and crying. That’s the best scene I’ve ever been in. Ever.”

There’s a theme there. Juan in Moonlight, the drug dealer/father figure; Don Shirley, the gay piano genius; Wayne Hays, a lead black detective in serialised television. We’ve not seen these kinds of characters before. With every choice, Ali is enlarging the perception of African-Americans in popular culture, and departing from what he calls “the canon of black characters”.

Which is why it’s surprising that Ali is reluctant to talk about it. He’s been an important part of this recent flourishing of black faces in Hollywood, both before and behind the camera, both male and female. It wasn’t so long ago that #OscarsSoWhite was trending on Twitter. I want to ask him how that change feels on the inside, but he sighs. A friendly sigh, but still.

“It’s just that white actors are only asked about race if they’re doing a civil rights project,” he says. “In interviews like this, they talk about their process and life, but black actors are always talking about diversity, where the culture’s at, where it’s going. We have to be professors of cultural studies where a white actor can just be an actor!”

He still gives me his best answer, though. He’s too nice not to. And it amounts to this: of course the changes are positive, but let’s see if they stick. All he knows is, he’s going to do his bit. He recognises his responsibility as a black actor of prominence. “My job is to push culture forward, and push the conversation.”

When Ali gets home today to Mount Washington, he’ll get to work on the script he’s been writing for a couple of years, a project he might direct. He won’t say what it’s about, but I’m told there are no sex scenes. He also has a production company, and a deal with HBO to create projects, some of which he’ll star in, but not all. “But mostly I just listen. I call it deep listening. Trying to hear where the culture’s going, and where the gaps are. What’s going to have resonance in two or three years, you know?”

Farrelly calls him monk-like. “He’s a bit of a holy man, Mahershala. He doesn’t drink, doesn’t smoke, doesn’t swear. I’m always saying. ‘What the fuck, man’, that sort of thing, and at first I kept apologising. But he said, ‘No, no, no, Pete, that’s who you are, don’t change!’ And that’s who Mahershala is. He holds himself to a very high standard, but he doesn’t judge.”

Perhaps this is why he elicits such reverence from his friends. And me too, I guess. It’s so rare in this life to find people of such unbending principle, who have elected to live their lives within the lines, and yet can look beyond them easily and without condescension.

I want to go home and deep listen now too. Push the culture forward. Think less about money and more about the work. Life seems more meaningful now than it did a couple of hours ago. I want to get after it. Stop faffing about. After all, here’s a guy who made some deep choices and stuck with them, and look at what it’s wrought. I can feel my squiggly lane in life start to straighten.

When the bill comes, we tussle for it, of course. But I win. He gets up to leave, bowing and clasping like before. “Thank you, brother!” he says. “See you at Habitat. Next one’s on me!”

And just as he disappears out the door, the waitress comes over and says, “He comes here a lot. Such an awesome guy.”

Green Book is in cinemas now.

Pick up March/April issue of the new Esquire now.

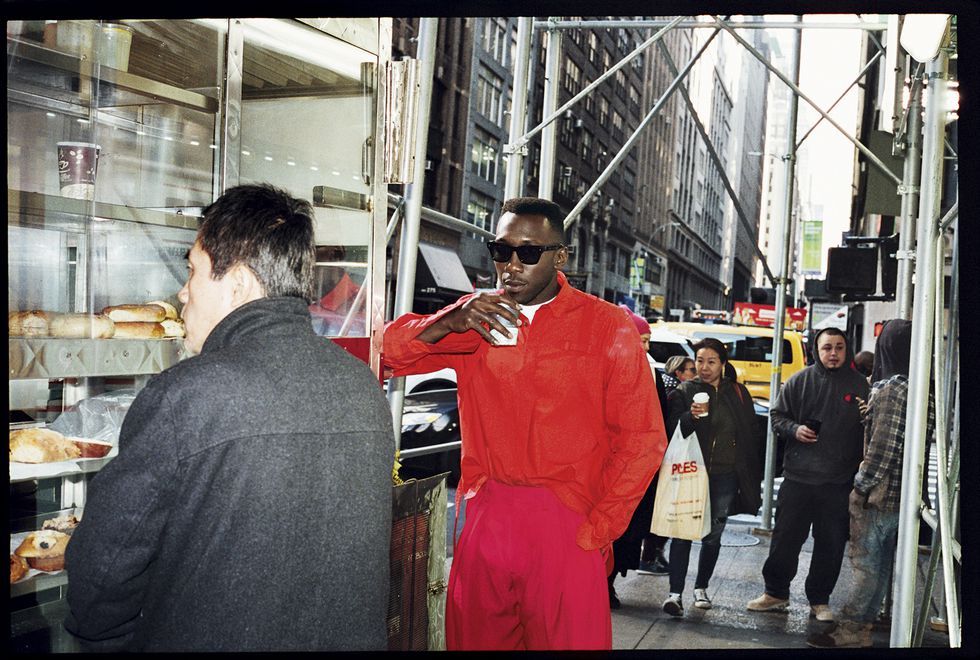

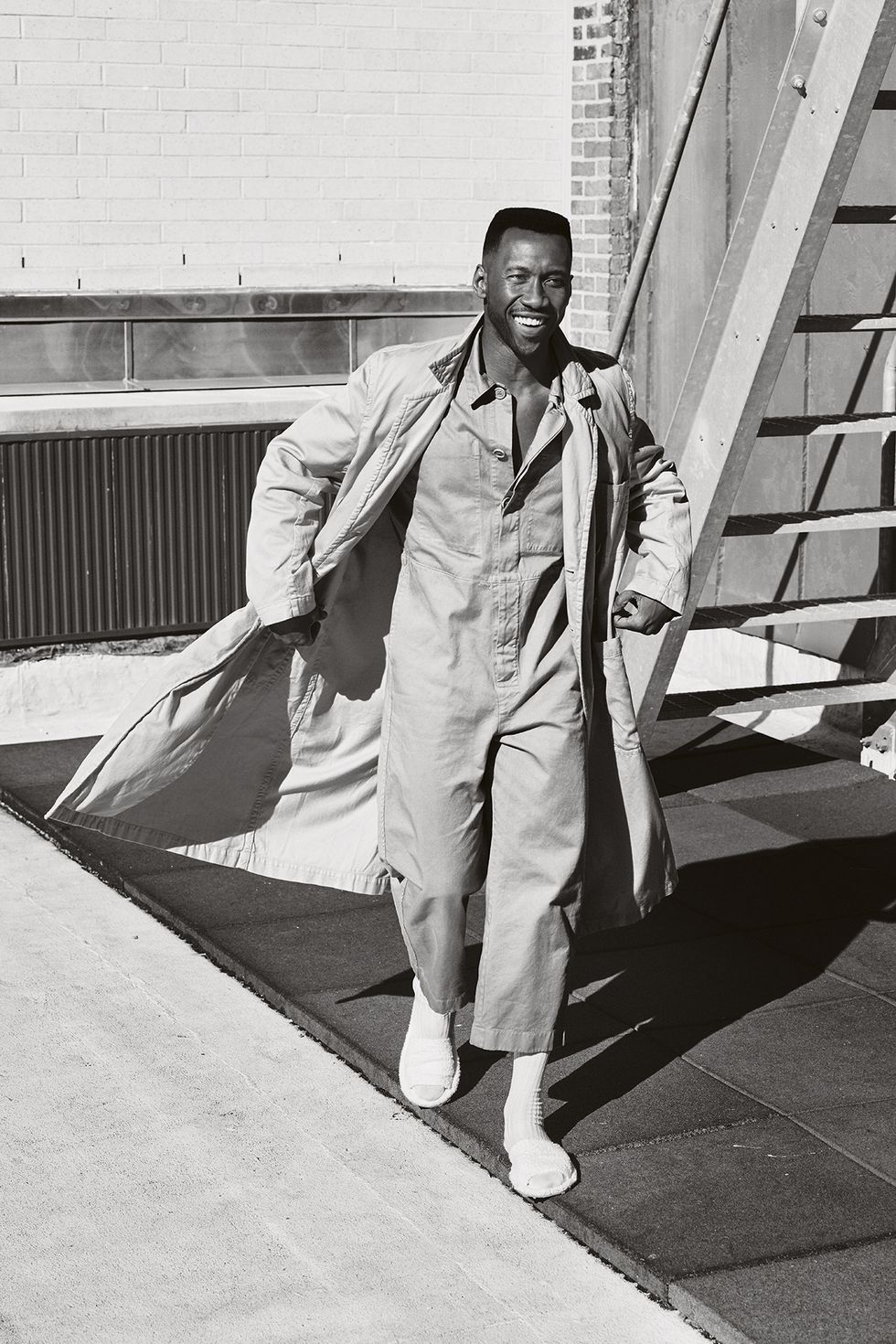

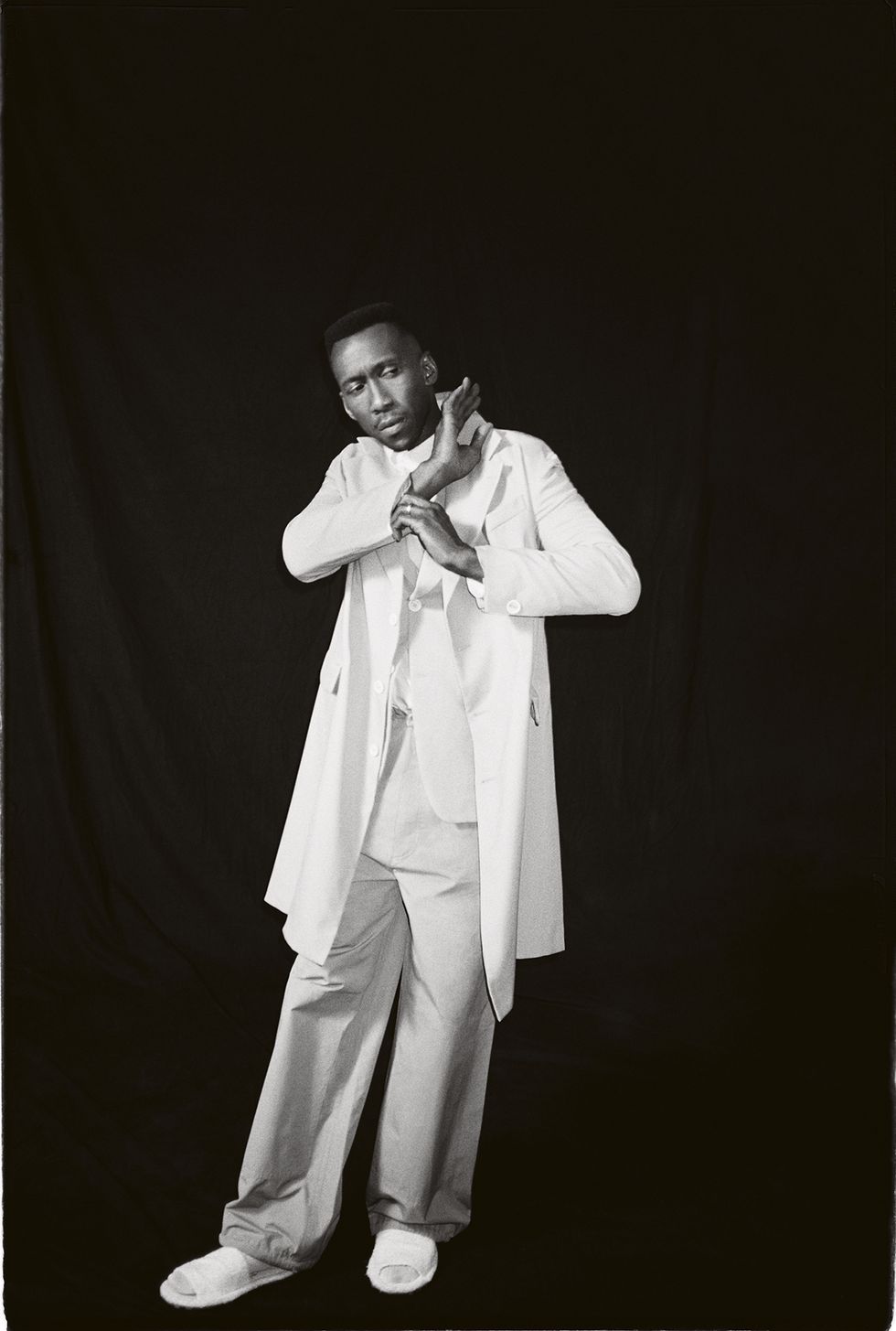

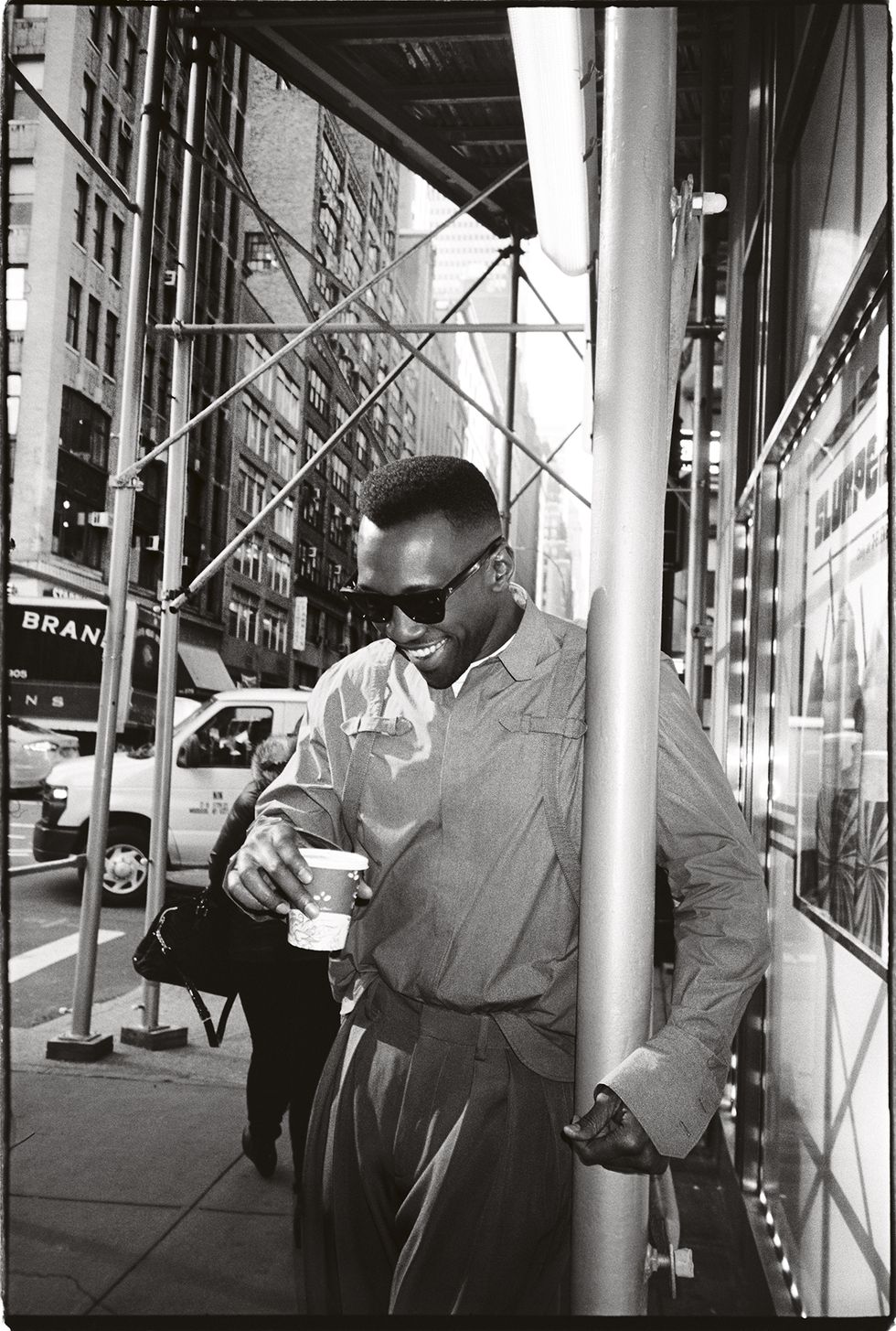

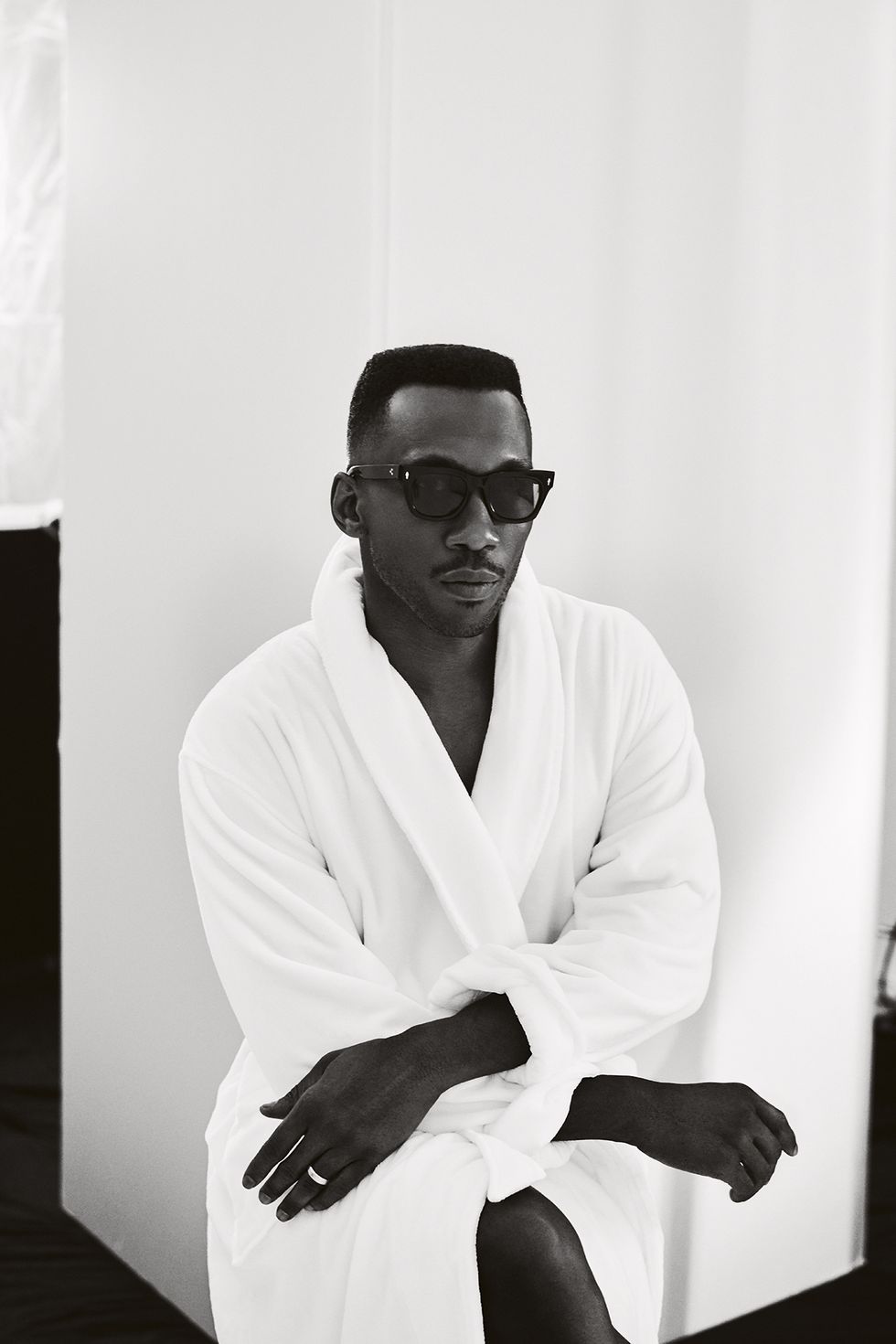

Styling by George Cortina

Lead image: Light green cotton suit jacket, £1,325; black cotton T-shirt, £305; light green cotton trousers, £350, all by Versace