Though Oppenheimer is a staggering portrayal of the man (played by Cillian Murphy) who helped create the atomic bomb and the emotional turmoil that sprung from that achievement, there are some notable unserious moments in the film.

The sex scene with Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), for one, quoting the famous line from Bhagavad Gita that he would also later exclaim once the test bomb Trinity exploded; mid-shag. But the other odd moments are when the unmistakable fuzzy-haired head of Albert Einstein (Tom Conti) pops up.

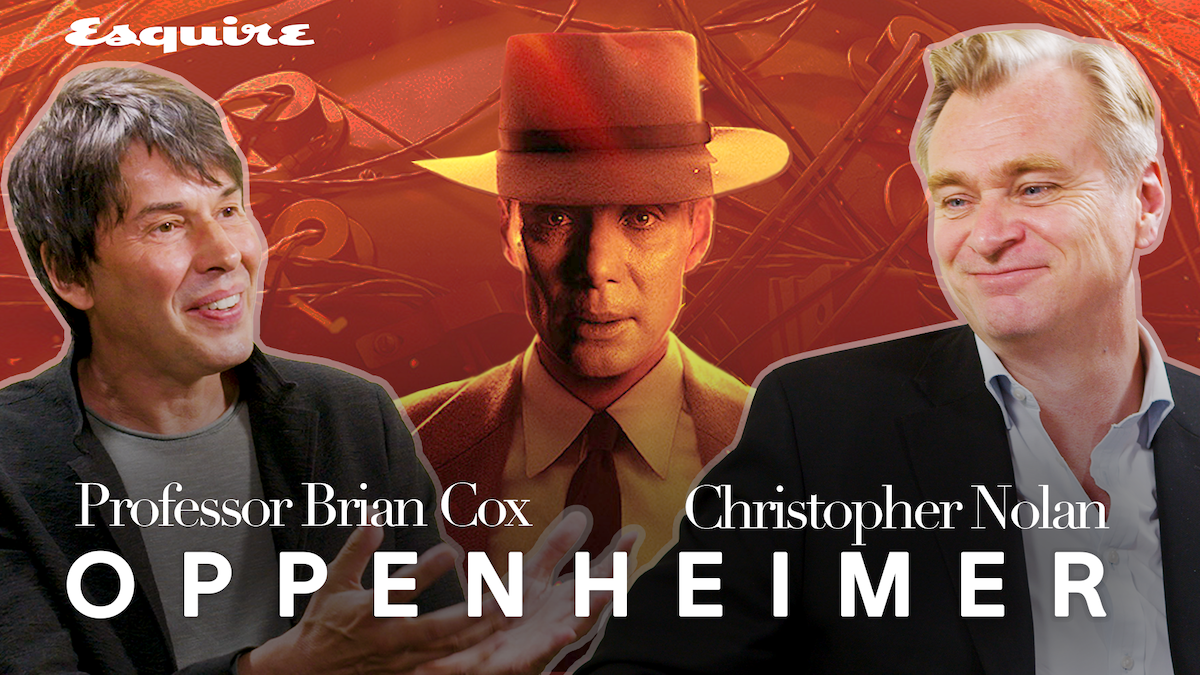

The pair, of course, were well known to each other, as they both worked in the same field, in America, at a similar time period, so we know it’s not the writer and director Christopher Nolan using artistic licence to place them together.

As J. Robert Oppenheimer wrote in the New York Times in 1966: “Though I knew Einstein for two or three decades, it was only in the last decade of his life that we were close colleagues and something of friends,” which is when they held positions at Institute for Advanced Science in Princeton, with Oppenheimer working there from 1947, and Einstein, until his death in 1955.

However, there’s just something incongruous about one of the most recognisable faces from history turning up in the film, a few minutes into the three-hour opus with a ‘gust of wind’ hat reveal, and at the end of the film to have a poignant chat with Oppenheimer about what he had wrought on the world.

It doesn’t help that Conti looks like he’s off to a student fancy dress party in all that get up; a Doc Brown-ification of the man that almost feels absurd when he appears on the giant IMAX screen in all his glory, stopping just short of sticking out his tongue. As one Twitter user put it: “Every time Einstein came on screen during Oppenheimer I was laffin. I know they knew each other but. It feels like putting Santa in the Serious Movie.”

Perhaps it also feels like burying the lede; having one of the best-known (and visually recognisable) scientists play a cameo in the film about one of his colleagues. But although Nolan imagined the pair’s conversation at the end of the film, where Einstein tells him, correctly predicting his future: “Now it’s your turn to deal with the consequences of your achievement. One day, when they’ve punished you enough, they’ll serve you salmon and potato salad. Make speeches. Give you a medal. They’ll pat you on the back and tell you all is forgiven. Just remember it won’t be for you. It’s for them”, it is similar in tone to a real chat the pair had.

The author Kai Bird – who co-wrote American Prometheus, from which Oppenheimer is adapted – noted that in 1954, shortly before Oppenheimer’s court hearing that would see his security clearance being revoked: “Einstein argued that Oppenheimer 'had no obligation to subject himself to the witch hunt, that he had served his country well, and that if this was the reward she [America] offered he should turn his back on her.”

Oppenheimer refused, as he said he loved his country, and apparently told his secretary that one of the most world-renowned theoretical physicists, probably for the first time in his life, “didn’t understand”.

“But as Einstein walked back into his office,” added Bird. “He told his own assistant, nodding in the direction of Oppenheimer, 'There goes a narr [fool in Yiddish].’”

The figure of Einstein in the film, be it in all of his archetypal glory, does work to highlight the meeting of these two extraordinary minds though, and to ponder what might have happened if the positions were reversed; and it was Einstein who discovered how to make an atomic bomb instead. Would history have played out in the same way?

In the final scene, Oppenheimer asks him: “When I came to you with those calculations, we thought we might start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world”, to which Einstein replies: “I remember it well. What of it?”. Oppenheimer replies; “I believe we did.”

The ominous tone of the men overlayed with the suggestion that the destruction of this world is still imminent: suddenly, no one’s chuckling at the wild-haired scientist on screen anymore.