This month marks ten years since David Fincher released The Social Network, a cri de cœur against Mark Zuckerberg, and a film which has proved prophetic in how seriously it took the ego behind the monster of Facebook and the seductive power of tech. The social media behemoth, which now owns both Instagram and WhatsApp, is now widely recognised as an endless hell-feed of misinformation and conspiracy which nobody has the power – or in Zuckerberg's case, the inclination – to control.

When the film was released the scandals that have hit the company were still a long way in the distance, and yet scriptwriter Aaron Sorkin and director Fincher tapped into Zuckerberg's capacity for indifference before it became common knowledge. "I like characters who don’t change, who don’t learn from their mistakes," Fincher said when the film was released in 2010. In the time since, Zuckerberg, much like with the director's characterisation of him, seems to be a man who refuses to learn from his mistakes.

Yet perhaps the element of the film that has proved more prescient is how it captures the kind of repressed male anger which has since crystallised online. The Social Network can be read as exploring a similar kind of underground anger as in Fight Club, Fincher's 1999 film which celebrated its 20th anniversary last year. Based on Chuck Palahniuk's book of the same name, Fight Club is a fictional story which imagines groups of men who beat each other up as a way of making them feel more alive. Palahniuk has spoken about how many men have approached him asking about real fight clubs, attesting to the power of his fiction by revealing they also felt they had unearthed some deeper truth about society and wanted to withdraw from it in protest.

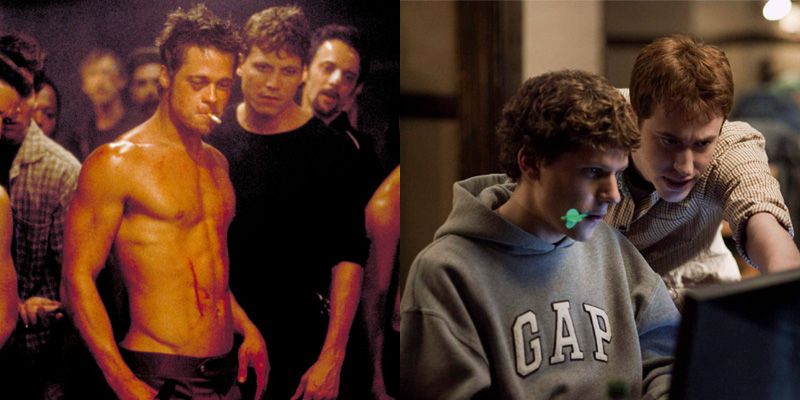

In Fight Club, we are shown a satire about commercialism and the broken American dream, where disenfranchised men forge an alliance through violence. The point is exaggerated to make a point about male ego and bravado, with the shirtless alpha Tyler Durden symbolising the fantasies hidden in the mind of the narrator, and men just like him.

In the near decade between Fight Club and The Social Network, the internet swept in and gave angry young men their own boxing ring to fight in every night, with forums, sub-reddits and social networks allowing people to anonymously remonstrate with strangers and spill their bitter musings. The two films make for interesting symbols of how masculinity has evolved in a short space of time, with each offering up an antihero for the furious, and marking the ways in which male rage has gone underground. If you want to hear the sound of macho fury nowadays, you're better off looking at the comments underneath Emily Ratajkowski's Instagram uploads than going to your local gym to lift weights.

Despite opening to mediocre reviews and poor box office numbers, Fight Club's relevance has only increased in recent years thanks to it being adopted as a Bible for incels, as Palahniuk noted in a recent interview: "It shows how few metaphors men have. Just that and The Matrix". While it was intended as a warning about repressed male anger, it has since been misread as a how-to guide for men to reject society and celebrate violence as a way to feel something.

Yet Fight Club would perhaps never have had this renewed interest if it weren't for the focus of Fincher's next film, as in the story of Facebook's beginnings The Social Network shows us an empire built by a man who seems motivated by fucking over his classmates and getting revenge on the girl who dumped him.

In Facebook's origin story you can see that the fantasy of the society-hating, master of chaos alpha male Tyler Durden has now given way to the bitter keyboard warrior, one who writes that his ex-girlfriend is a bitch on a website first conceived as a way to rank the women at his university, and calls his classmates "dumb fucks" for trusting him with their information. In the time since The Social Network, Facebook has become home to hives of racism and misogyny, such as the far-right group Proud Boys, and to conspiracies like QAnon which thrive on the Fight Club-esque mentality that society is a duplicitous illusion. Meanwhile, as on social networks like Twitter and YouTube, death and rape threats are exchanged freely.

The Social Network is a different kind of middle finger to society – and perhaps one that angry men are less keen to identify with – but both feel like rallying cries for marginalised men taking what they believe is theirs. Zuckerberg might be a "beta bro" rather than an alpha male, but he's still a man who became a billionaire, seemingly mostly as a fuck you to those who wouldn't let him join in or broke up with him. A man with a level of bitterness as Fight Club's nameless narrator who wanted to, "destroy everything beautiful I'd never have."

20 years after Fight Club's release, we saw what many touted as the spiritual sequel to Fincher's film in Joker. Todd Philipp's movie drew a straight line from the lost generation of Fight Club, whose fury and frustration at society boiled over into brutality. It was another story about a man man who reacted to the circumstances of his life by withdrawing from society. When backlash inevitably followed, Philipps promised that he wasn't trying to glorify violence, but in truth, he'd lost control of his story's true meaning the minute it reached the angry young men of Facebook. Mark Zuckerberg has helped to make sure of that.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox