When Heat came out on Boxing Day in 1995, it already carried some fairly hefty hype and heat of its own.

For starters, the relentless bank heist scene, filmed on 5th street in downtown Los Angeles, was going viral as a cinematic event in itself, largely thanks to a quirky pre-internet communication channel known as word of mouth.

And the word was, even if just for the noise and choreography of this sequence, you needed to see this film fairly urgently.

Then there was director Michael Mann, who had acquired a growing fanboy following for a style characterised by obsessive preparation, experimental scores and starkly beautiful framing, which combined to give an auteur’s flourish to otherwise fairly mainstream stories; perhaps most notably in Manhunter, nine years earlier.

And on paper Heat’s storyline is pretty conventional. A cat and mouse thriller pitching a ruthlessly professional criminal called Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro) against a ruthlessly professional police detective called Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino), it is elevated, first and foremost, by the earnestness with which Mann – and, in turn, everyone else involved –approaches it.

For nine months in the run up to Heat, Mann went out every Friday and Saturday night with LAPD officer Tom Elfmont in the name of research, answering emergency calls all over the city, often until the early hours.

As well as feeding in to the film’s look and feel and dialogue, it’s on these stakeouts that Mann says he truly came to know Los Angeles, and this film is also an LA movie like no other.

More than anything, though, the buzz on its release was centred on De Niro and Pacino, famously on screen together for the first time.

For those lucky people too young to know, the excitement and significance of this casting back in 1995 cannot be overstated (as a then 18 year-old weaned on The Godfather and Goodfellas I was an open-mouthed on-the-ground witness).

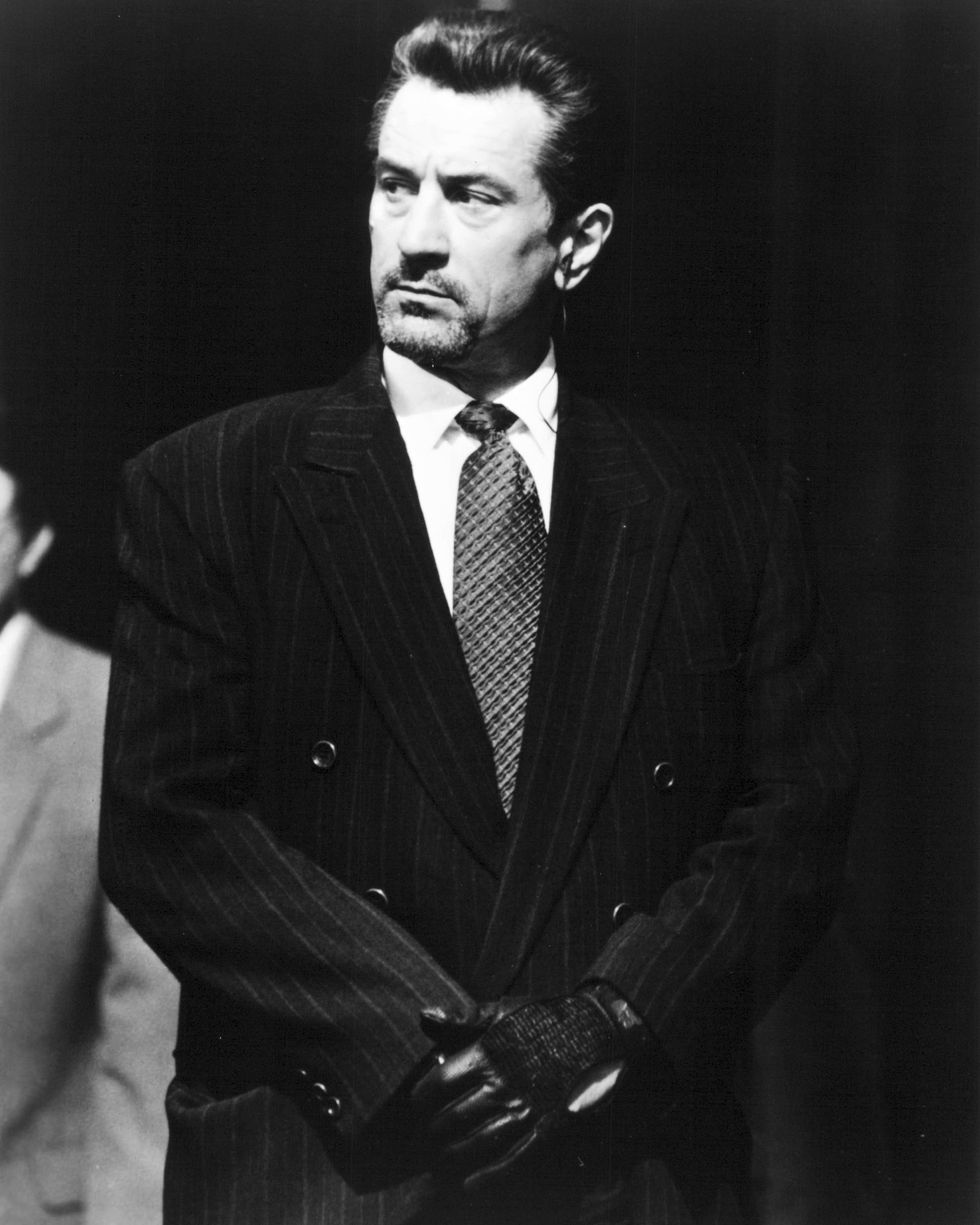

In some ways, here was De Niro in his absolute prime; old enough to have accrued more range and life experience, still young and fit enough to carry the old menace.

It was also just before he said yes to everything. His next film was The Fan. There’s an argument to be made that Heat is his last great film and performance.

Pacino, all coiffed hair, gold chains and chewing gum, was on something of a comeback after Frankie and Johnny, Scent of a Woman, Glengarry Glen Ross and Carlito’s Way had pulled him out of an epic Eighties slump. Heat marked the first part of the career phase when he reeaally started shouting.

That these two - like two great heavyweights from different divisions whose paths had somehow never crossed - were playing co-leads, two sides of the same coin, a detective and criminal that would battle it out until the end credits made the billing almost too much for an adolescent film fan to take in.

De Niro’s Neil McCauley is smart, quiet and focused; a reserved career criminal who listens, assesses and only speaks when it’s absolutely necessary. When he does he invariably sounds like he’s writing a self-help book for bank robbers: “don’t have anything in your life you can’t walk out on in 30 seconds flat.”

He wears a grey double-breasted jacket to accentuate the idea of a guy whose whole life is engineered to blend in to the background. Which kind of doesn’t work, because it’s hard not to notice that this is one really good jacket.

His unfurnished beach front home, again carefully selected to communicate loneliness, was deliberately shot in a monochrome filter.

What the goatee beard represents is less clear, although somehow he pulls it off; surely the only such example that has successfully survived the Nineties.

It’s one of De Niro’s most contained and, perhaps because of it, compelling performances.

Pacino on the other hand knew he had to play his counterpoint in a different “colour”, as he calls it. He’s revved up and jacked up throughout, never missing the chance to raise his voice or click his fingers.

During a live Q&A in 2016, he admitted that he played his character Vincent Hanna as a constant cocaine user, which goes some way to explaining some of his delivery.

“He’s a guy who chips cocaine,” he said. “That was a choice we made and yet not showing it because it would be too (obvious).”

Perhaps the most memorable example of this character trait is the scene in which Hanna questions Hank Azaria’s very reluctant informer.

With the scene already safely in the can, Pacino gave Mann the nod that he was going to try something a little different. No one told Hank Azaria. The result is the famous wild-eyed, “Because she’s got a greeaaat ass!” Azaria’s on-screen bafflement is genuine.

Like all great thrillers, it’s a film of memorable “bits”. The opening truck heist; Waingro in the car park; the diner scene; the shoot-out; the bit where De Niro reveals his unusual flirting style: “it’s a book about metals.”

Plus a contender for what might just be the most menacing and memorable telephone scene in film history.

For all the plaudits Mann gets for the way his films look, Heat’s classic status owes more to its endlessly quotable dialogue and remarkable action set-pieces.

When it later became a regular on late-night terrestrial TV, if you happened to be flicking the channels before bed and you caught Heat already underway, your heart would initially sing and then sink slightly. It looked like you were staying up late after all.

The Diner Scene

To add to the Heat legend, there was a rumour at the time of release – which persisted for a decade or so - that De Niro and Pacino didn’t actually appear on set together, fuelled by the fact that their faces don’t appear together in the same frame.

In the film’s flagship diner scene, filmed in the famous Beverley Hills restaurant Kate Mantilini which closed in 2014, the two face off in a cinematic moment that also serves as the nucleus and turning point of the entire story, as the two foes look each other in the eye in the hope of finding an edge.

It was clear during filming how significant this scene would become too, so why didn’t Mann use a wide shot?

“I hadn’t intended on excluding a wide shot until the editing,” Mann told AP in an interview. “Every time we (Mann and editor Dov Hoenig) put that shot in, it let the air out of the balloon. It deflated the intensity. When you stopped being empathetically projected over Al’s shoulder of Bob or vice versa, but then became an observer looking at the two of them, it stopped being quite as intensely immersive.”

Watch it again and you can see what he means. Mann used a black and white background to reduce distraction and in the context of the story, the scene crackles with intensity.

They didn’t rehearse it properly on De Niro’s suggestion, so as to keep it as fresh as possible; only giving it a cursory read-through before shooting.

It was past midnight by the time the cameras came to roll, far later than De Niro, for one, was happy with for such an important scene. Ultimately, it was take 11 that was chosen.

“I knew they would be completely alive to each other—each one reacting off the other’s slightest gesture, the slightest shift of weight,” said Mann to the Directors Guild Of America. “If De Niro’s right foot sitting in that chair slid backward by so much as an inch, or his right shoulder dropped by just a little bit, I knew Al would be reading that. They’d be scanning each other, like an MRI.”

The exchange also gives us the ‘Heat’ of the title: “A guy told me one time,” says De Niro’s McCauley. "Don't let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner."

And yet here was the heat – the police - right in front of him. McCauley also lets slip that he has “a woman”, which gives Hanna (Pacino) information that will ultimately prove McCauley’s undoing. For all his pontificating, McCauley fails to practice what he preaches.

The Backstory

If anything the diner scene seems a little far-fetched. Would a cop really invite his nemesis for a coffee and catch-up that flits between repressed bromance and murderous threats?

In fact, the scene – and indeed the film’s entire premise - played out for real in almost identical fashion in the Sixties.

A detective friend of Mann’s from Chicago called Charlie Adamson who worked in the Chicago police department and would later work as a writer with Mann on Crime Story and Miaimi Vice in the Eighties, had once “enjoyed” a mutual respect with a career criminal named Neil McCauley.

Adamson respected his professionalism, albeit as a crook, and after inviting him for coffee one day, had an honest exchange that ran almost verbatim to the one that would find legend in Heat.

“They wound up having one of those intimate conversations you sometimes have with strangers” says Mann in ‘Michael Mann: Crime Auteur’ by Steven Rybin. “There was a real rapport between them; yet both men verbally recognized one would probably kill the other.”

Sure enough, Adamson shot and killed McCauley during the aftermath to an armed robbery in 1964.

Mann loved the story straight away because of what he calls the duality of the set-up; the chance it afforded to have two protagonists you can root for on different sides of the law.

And sure enough, each time you watch it, even if you’ve lost count of how many times you’ve seen it before, you’re still not sure who you want to come out on top.

The Prototype: LA Takedown

Mann wrote a draft screenplay as far back as the late 70s but parked it after making Thief with James Caan as he didn’t want to do another crime story.

In the Eighties, he offered it to Walter Hill to direct, who declined.

Mann then got an offer to try it out as a pilot for a TV series, in what came to be known as LA Takedown.

Taking out over 100 pages from the original script to fit the small-screen format, Mann had been given the strange quirk of a trial run at Heat; what Mann now calls “a prototype” – though critics would have less neutral words to describe it.

Mann told the BBC that comparing the two is like comparing freeze dried coffee with Jamaican Blue Mountain and the difference as "cosmic”.

For a start, LA Takedown had just 10 days of pre-production. Heat had 6 months. LA Takedown had a 19 day shooting schedule. Heat’s was 107.

And if you want an example of what really good actors bring to the table, watch the diner scene from LA Takedown if you dare.

The TV show never happened of course - Mann and NBC disagreed over casting so Mann walked away, still with ownership of the script and story. But Mann learned a lot that he would take into Heat five years later and unsurprisingly wishes he could do it with every film.

It was only after completing Last of The Mohicans in 1992 that he came back to the original script with a new idea on how to end the film.

Working backwards, he saw that the entire story was a collision course towards the final time these two protagonists meet at LAX airport.

The Making of 'Heat'

Mann had breakfast with producer Art Linson in the same restaurant in which De Niro and Eadie meet each other at the bar. Mann was still thinking of producing, not directing. Linson’s response after reading the script was “Are you crazy?”

It was obvious to them straight away that the two lead roles were meant for De Niro and Pacino. Or Bobby and Al if you actually work in these circles.

Mann talked to Al, Linson talked to Bobby. After detailed chats, both said yes there and then.

For all the starriness of De Niro and Pacino’s casting, it was treated as an ensemble piece. Mann has described it as a repertory feeling on set.

With storylines spanning out into the almost mundanity of its characters personal lives, not unlike a Robert Altman movie, he need the wider cast to be strong and deep. It’s hard to think of one role that doesn’t ring true.

Mann had always wanted to work with John Voight who needed some persuading to play criminal fixer Nate – part-crime gang PA, part-life coach – who sports a memorable mullet hairstyle and croaks his way through a perfect comeback performance after a decade or more on the margins. (Chernobyl: The Final Warning anyone?)

Val Kilmer – at that time one of the most bankable stars in cinema – was shooting Batman whilst Heat was in pre-production. He has since said the best bit about Batman was preparing for Heat. He’d even show up on days when he wasn’t shooting to watch.

At one point, Keanu Reeves was lined up for Kilmer’s part but turned it down to play Hamlet on stage in Canada.

Preparation was intense. Mann had already spent time in Folsom Prison for the film Jericho Mile, and took several cast members inside to pick up anything that could help ground these characters in reality.

Over 100 different locations were used to show a very different side of LA. Mann’s belief that architecture can be used to make the audience feel a certain way is on show from the opening five minutes. Almost every shot is framed in a way you’d be happy to hang as a photograph.

As preparation for the bank heist, De Niro, Kilmer and Tom Sizemore even cased out a working bank. With weapons. The only people that knew were the security.

The Bank Heist

What must rightly claim a place in any shortlist of the greatest shoot-out scenes in film history comes a full 1 hour and 50 minutes in but always rewards you for your patience.

The tension builds beautifully through the relentless ticking of Elliot Gould’s score as McCauley’s crew depart the bank and head for the getaway car unaware that the police are lying in wait.

When Kilmer’s character spots them across the street, he immediately starts firing and what follows is an expertly choreographed sequence of ferocious noise and intensity that was carefully planned months in advance.

The hand-written shooting plan was appropriately codenamed ‘World War Three’.

It was shot over three consecutive weekends because they didn’t have permits to shoot downtown during the week.

Former SAS man - and Alan Partridge’s favourite author - Andy McNabb (Bravo Two Zero) was on the team who designed separate training regimes for the two different crews, using live ammunition on the shooting ranges and full-load blanks (which contain full charges of gunpowder) on camera.

The chilling sound of gunfire reverberating around the steel and glass surroundings is the actual live sound of shooting. For each take, an estimated 800-1000 rounds were used.

So well versed with the weapons did the actors become that Kilmer’s technique for loading and reloading have been used by South Carolina special forces: “If you can’t reload as quickly as this guy then you shouldn’t be a soldier.”

Perhaps it was too authentic. Just over a year after Heat was released, a shockingly similar scene played out on the streets of North Hollywood as two bank robbers with a cache of fully automatic weapons and in full body armour engaged the police in a 44 minute shoot-out using armour-piercing bullets which injured 11 police officers and six bystanders.

Some of it was even shown live on TV as news helicopters buzzed overhead.

Watching the scene today, its power still lies in the fact that they did it for real. No CGI. And the same is true of every other set-piece in the film, including the final airport showdown where real airliners were vibrating overhead as they filmed. It was also shot the same week as the Unabomber bomb scare at LAX.

As De Niro and Pacino stalk each other in the shadows,‘God Moving Over The Face Of The Waters’ by Moby provides the perfect soundtrack.

McCauley dies holding hands with the only other guy who understands him. This was the ending that Mann had been looking for.

Reception and Legacy

Released in the heart of awards season and with an expectant campaign from Warner Bros to back it up, it’s peculiar now to think that Heat received not a single Oscar nomination.

Aside from the actors, Mann would have been an obvious contender as would Spinetti’s cinematography, the sound design, editing; the list goes on and on.

That year, Chris Noonan picked up a Best Director nod for Babe. Mel Gibson won for Braveheart.

Had it been dismissed as just another tale of cops and robbers? Let’s face it, the Nineties were full of them.

While Mann clearly hates the idea of Heat being considered a genre film – a crime movie – it’s fair to say that there is the occasional shaky plot-point and police procedural cliché.

At one point Pacino actually says the line “Don’t you get it? It gets knocked back to some chicken shit misdemeanour they do six months and then they’re out... They will walk away and you will let them.”

In Mann’s defence, this scene was also taken from the real-life case his friend Charlie Adamson had told him about but such moments might explain why the critical reception at the time was mixed and a little muted. The box office too was only decent, not spectacular.

For Mann, it’s actually about the messiness of human connections and lives lived at the extremes.

He wanted to show how these characters’ personal lives played into their decision-making further down the line: “Its plot is driven by a crime story and a police story to a certain point, and then it breaks into a kind of chorus. In that chorus, we see slices of these different people’s lives.”

Some say it’s baggy because of it, but the more times you see it, the more you realise that this is what makes it. It can be read as deeply or shallowly as you wish. It works either way.

Perhaps it’s why it picked up momentum on DVD and terrestrial TV, where these backstories felt a little more at home.

Mann produced so much backstory in fact that he has since been working on a novel that serves as both prequel and sequel, with the plan to turn it into a movie.

The influence of Heat can be seen far and wide, not least on Christopher Nolan. The LA skylines, minimalist soundtrack and even the casting of William Fichtner in the same sleazeball role, gave the The Dark Knight an unabashed ode to Michael Mann. Nolan has since admitted as much, even chairing a 20th anniversary Heat Q&A.

Perhaps the greatest compliment is that the film is unlike anything else from the era, but instead now carries a classic quality. Goatee aside. Time is a healer too and Heat’s status has grown, its few vices now recognised more as virtues.

The work that went into it reveals why the film reveals something else every time.

Its modern classic status has been a slow-burner. But it’s not hard to see the film being watched in another 25 years as one of the all-time greats.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts