Writing a James Bond film is hard.

You have to do something fresh and new, but within certain Bond-ish parameters. You want to open up new sides to Bond himself, while also respecting the history of a character who’s been in the culture since before Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation. You want to do something big and spectacular, but without accidentally making Die Another Day.

“I believe that the key to a successful Bond movie is always doing the same thing,” the Moonraker and The Spy Who Loved Me writer Christopher Wood once observed, “only doing it differently.”

Before starting work on No Time To Die, Neal Purvis had worried aloud that he was “just not sure how you would go about writing a James Bond film now” given how quickly and suddenly the world has convulsed at times in the last decade. But however much things have changed around Bond the character, for Anthony Horowitz his appeal is simple and undimmed.

“Despite the fact that some of his attitudes and his actions are at variance with how we now see the world, I've always admired the character very much,” says Horowitz, author of the James Bond continuation novels Trigger Mortis and Forever and a Day.

“He's always been for me very much what Kingsley Amis described as the dark knight, the romantic hero, if you like – the Clint Eastwood figure, the man with no name, who rides in, saves the world and then disappears into the horizon.”

Before you get started, though, you should probably resign yourself immediately to the first law of Bond writing.

Law one: Leave your ego at the door

Producers Barbara Broccoli and Michael G Wilson are the ultimate arbiters of what does and doesn’t happen. There will be rewrites. There will be rewrites of those rewrites. There will probably be rewrites of the rewrites of the rewrites.

“The process is very, very long and very collaborative,” says Bruce Feirstein, who led on The World Is Not Enough and contributed to both Tomorrow Never Dies and GoldenEye.

This suits some writers better than others. Christopher Wood, who worked on The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker suited it less well.

He wasn’t a fan of Moonraker’s Star Wars-lite premise and worried that the action scenes wouldn’t work. “It is difficult to rush around in an astronaut’s suit,” he recalled in a 2012 interview.

Still, he knew not to rock the boat: “Did I tell Cubby [Broccoli] that his idea sucked? No.”

On Spectre, longtime writers Neal Purvis and Robert Wade were airdropped in to change the third act when pre-production had already started. The executives didn’t know what they wanted; they just didn’t want what they had.

“And sometimes they couldn’t decide what they wanted until they’d seen it written,” Purvis told the Telegraph. “So you write scene upon scene upon scene. You write so much.”

On the phone, Feirstein tends to draft and redraft sentences a couple of times before landing on his preferred construction.

“Barbara and Michael are incredibly hands-on, involved at every step of the way and kind of…” He pauses. “I want to find the right phrase here but... Barbara and Michael protect the franchise.”

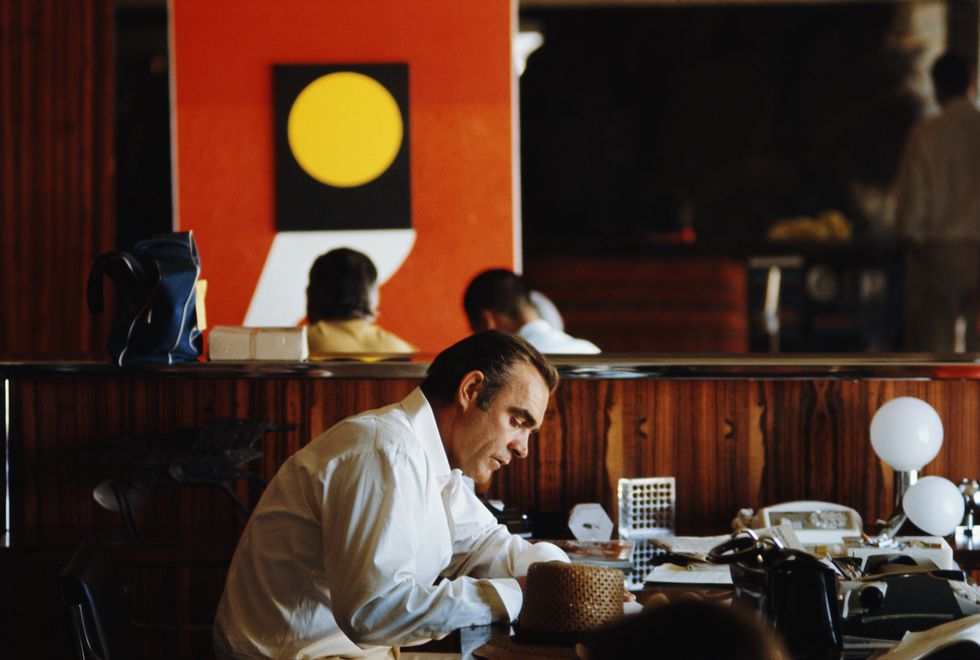

Broccoli, daughter of original Bond producer Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli, has been involved since working on the publicity for The Spy Who Loved Me in 1977; Wilson is Cubby’s stepson and Barbara’s half-brother, and started in 1972. The pair hold the institutional knowledge of Bond between them.

In Feirstein’s experience, a Bond story tends to begin in the same place.

Law two: Find a good baddie

“All of them start off with: what's the spine of the story? Who's the villain and what's at stake?”

Despite what decades of spoofs would have you believe a Bond villain was never, Feirstein says, a cartoonish figure.

“They were not moustache twirlers,” says Feirstein. “They were kind of like, cool and even-handed. We remember them as being gleeful, but they're not.”

Die Another Day’s Gustav Graves – a North Korean general who underwent ‘DNA replacement therapy’ to transform into a plummy, white, British establishment toff – exists on the same continuum as Licence to Kill’s drug lord Franz Sanchez. As Feirstein says, “Bond occupies a very particular quadrant of fantasy”.

Even the most maniacal megalomaniac needs to be grounded in a contemporary anxiety, but retain some of the escapist bombast which makes them compelling. There was a rule of thumb which Feirstein used to go by when it came to villains. Call it the Jeff Bezos Rubric.

“[The villain is] someone who can do anything that someone with an unlimited amount of money can do in the current culture. Can you hollow out a volcano? Probably. Can you time travel? No.”

Feirstein’s idea for Tomorrow Never Dies was for a Robert Maxwell-style media string-puller, a malevolent manipulator who used information as his weaponry. By the time he made it to the screen in the shape of Jonathan Pryce’s Elliot Carver, he’d turned into something slightly more lurid.

“You want to do something about a media villain,” Feirstein reflects, “and next thing you know, you've got a stealth boat with an underwater drill.”

When you have your villain, the real difficult questions start. Who is James Bond? And why should anyone still care?

Law three: Bond must make sense now

John Cork flips back and forth through a 64-page document and sighs, looking for a page. He’s an expert on Ian Fleming and the James Bond films, and has lent his knowledge to Broccoli and Wilson over the years. In the early nineties he was brought in to work on a treatment for a potential new film.

“And at a certain point early on, I said, ‘Before I spend more time trying to create villainous plots, who is the James Bond in this film?’”

At the time Bond was in an odd stasis. Legal wranglings prevented a quick follow-up to 1989’s Licence to Kill had stalled the franchise’s momentum, eventually leading Timothy Dalton to leave the role.

“Everything was on the table,” Cork says. “You could have taken Bond in virtually any direction whatsoever.”

So Cork put together what Feirstein calls “a kind of a bible” answering the fundamental questions: who is this man, and what’s the point of him? What can he do, and what can’t he do? What is his world, and how does he live in it?

There’s a lot he can’t tell about it, he says, but there are 11 pages of notes setting out the Bond the man, as well as how he interacts with the world, with the key figures in the Bond universe, how he should interact with women, and what kind of women he meets.

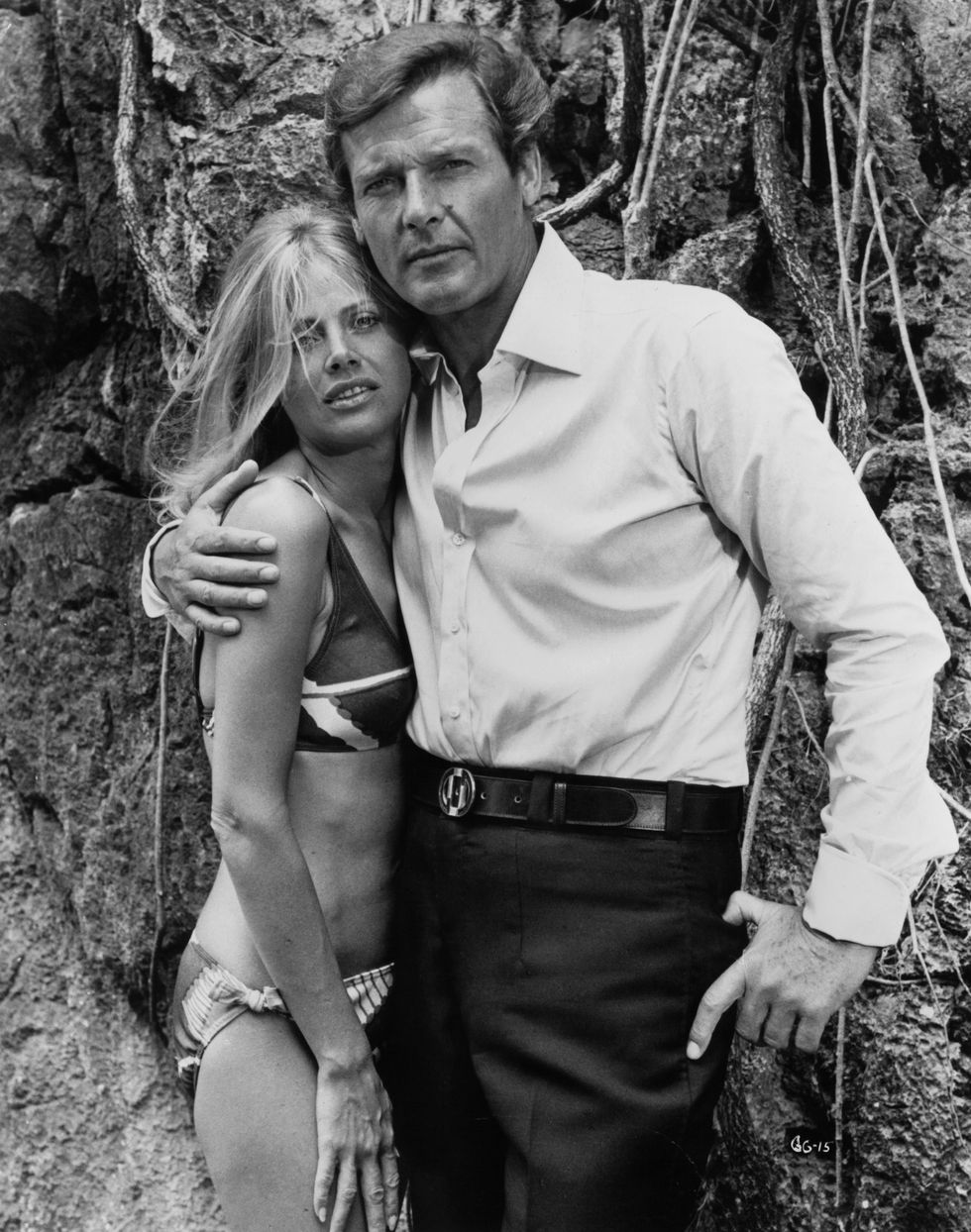

“One of the things I put in there is that they should be good at what they do. Bond should always assume that they are skilled, talented, so that you don’t end up with, like [Britt Ekland’s ditzy The Man with the Golden Gun character] Mary Goodnight.”

There are lines which Bond may not cross too. There are, for instance, no children in Bond films, as one corporate partner found when it proposed an advert which saw Bond saving a baby and saw it vetoed.

There were no hard and fast limits put on Anthony Horowitz by Ian Fleming’s estate when he wrote his two Bond novels, but sensitivities still had to be observed: “I think it was more a case of, you know, do what you want to do. But understand that if you step out of line, we will have to have discussions.”

One negotiation concerned Bond’s choice of nightwear. Horowitz wrote him as sleeping nude; the estate informed him that, actually, Bond wore something called a pyjama suit: “If you can imagine the top part of a pair of pyjamas, that starts at your neck and goes all the way down to your knees – that, apparently, is what Bond would have worn in bed.”

This struck Horowitz as intensely unsexy. A compromise was struck whereby Bond’s state of undress would remain unmentioned.

“That document was really rewarding to work on,” says Cork. “I went through all the novels again, which I have read many, many times, and pulled out core elements where I thought Fleming defined who Bond was in those books.”

The mantra that the next Bond film will ‘go back to Fleming’ is almost as much a trademark as the Aston Martin DB5, and most intensely at the end of a Bond actor’s cycle of films. Horowitz’s two Bond novels, incorporated unused material from Fleming himself, and knows Bond and his world better than most.

“I've always said that he would probably be a rather uninteresting dinner companion to have, because he doesn't go to the theatre, he doesn't reference films, he doesn't seem to have any strong musical tastes. He doesn't go to museums or art [galleries]. He doesn't seem to have a great deal of interest in anything very much.”

That, though, is part of why Bond endures; he is, says Horowitz: “the Byronic hero who doesn't need to go to therapy to work out why he does what he does – he just does it, gets on with it and leaves.”

Cork is fairly sure that nobody in the Bond camp has looked at his bible since before GoldenEye came out, and he’s glad.

“Art that does not change does not survive,” Cork says. “If you don’t restore The Last Supper, that paint will peel off the walls.”

Law four: Exploit the Bond-world

Writing Bond isn’t just about staying between the tramlines: you need to enjoy the latitude he gives you too. A scene from The World is Not Enough is a case in point.

“There's a woman on the Thames in front of MI6 in a red leather jacket with a 50-calibre machine gun on the back of a speedboat and, like, no-one notices,” says Feirstein.

“But you go with it, because the audience loves that shit. And that is the hallmark of a Bond movie.”

This is the fun bit. You get to throw Bond down lift shafts, stick a jetpack on him, tuck an exploding pen into his breast pocket. The audience’s tolerance for, say, invisible cars varies, but that’s not your problem. You get to play around with the fairly-possible and the near-ridiculous. Feirstein came up with a backpack which transformed into a pair of skis for a segment where Bond skied down a frozen waterfall in one script.

“And they built it! I saw it!” he says excitedly. “We didn't use it. But they did the gadget!”

There are, sadly, some rules there too though.

“He's got his wristwatch. He's got a belt. He's got shoes. But, you know, [Bond] and the villain cannot bend the basic rules of time, space and gravity.”

That goes for the big set pieces too, but again you need to place yourself in that quadrant of fantasy Bond occupies.

“When you look at the stunts that Daniel Craig has done, there's nothing there that can't be done. Ninety-nine-point-nine-nine-nine-nine percent of the time the person trying to do it would die. But Bond is the one tenth of one millionth of a percent.”

There are the quips too. Those cocky little put-downs, sly asides and dry bon mots go back to the work of Richard Maibaum, who wrote on nearly every film between Dr No and The Spy Who Loved Me. “There is no movie Bond without Maibaum,” Feirstein says.

Maibaum, he says, “infused Bond with his sense of humour,” turning him into “a character with a point of view”. The degree to which Bond cracks wise varies, but it’s always there. What’s been less common lately is the slightly Carry On names given to Bond women.

“I'll take credit for Xenya Onatopp,” says Feirstein. “Purvis and Wade get the blame for Christmas Jones.”

Perhaps the most terrible groaner in any Bond film certainly is Feirstein’s though. In The World is Not Enough, Bond and Dr Jones are in bed when Bond quips: “I thought Christmas only comes once a year.”

“Barbara and I were sitting somewhere and I said, ‘That's what the line should be!’ And she roared and she said, ‘That's horrible and ridiculous and not any good – let's use it.’”

In Bond films laws, much like the Highway Code, are made to be broken. But there is one last law of Bond writing which is simple, and written in stone: wherever you send him, whoever you throw at him, and whatever you do to him, James Bond will return.