Amazon’s new series Hunters bills itself as being inspired by true events, but you don’t have to watch more than the first few minutes to realise that the Jordan Peele-produced tale of Seventies New York Nazi hunters is only loosely based on the real people who’ve spent the 75 years since the end of World War II working to bring former Nazis to justice. Creator David Weil told Entertainment Weekly that when he heard stories from his Holocaust-survivor grandmother growing up, he saw them "as comic book stories, stories of grand good versus grand evil, and that became the lens through which I saw the Holocaust.” The series is full of comic-worthy action scenes, and features a Nazi-pursuing crew that includes an old married couple who happen to be weapons experts, a Vietnam veteran, and one very tough nun. They even call their headquarters the Batcave.

While it’s pretty cool to see Al Pacino, in his role as Holocaust survivor-turned-crime fighting team leader Meyer Offerman, wreck bloody vengeance on a sadistic former concentration camp guard, that’s not really how former Nazis have been brought to justice over the years. Real life Nazi hunters aren’t extrajudicial killers, but seek justice through legal means.

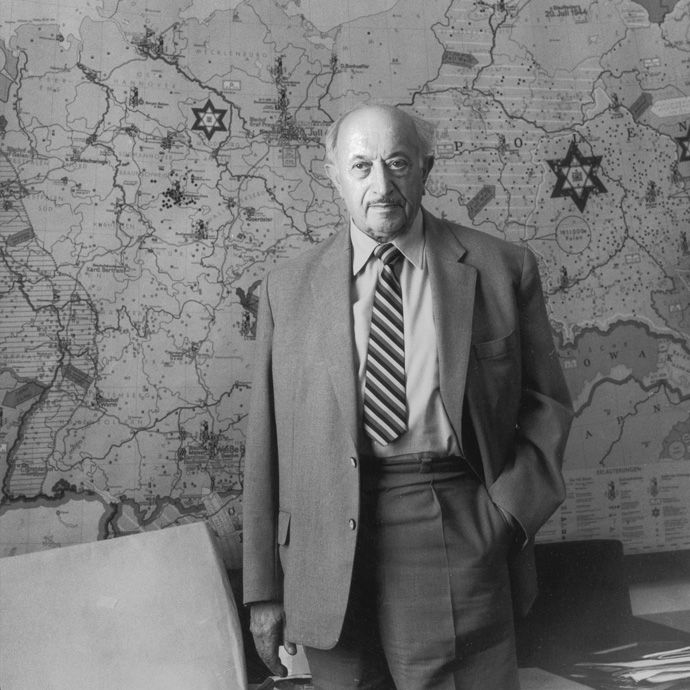

The most well-known of them is Holocaust survivor Simon Wiesenthal. Born in what is now Ukraine, Weisenthal was living with his wife and working for an architectural firm when they were forced into a labour camp. Though they would both survive the Holocaust, nearly 90 members of their families died. By the time his concentration camp was liberated, Weisenthal himself was near death and weighed under one hundred pounds. He’d made three attempts at suicide to escape the nightmares of the camp.

But as soon as he regained his health and freedom, he began working with the US army to document Nazi war crimes, and later devoted his life to tracking down former Nazis and assembling evidence to be used in their trials.

While Wiesenthal’s work helped bring more than 1,000 Nazis to justice, he wasn’t a vigilante like the characters in Hunters; in fact, his motto was “justice, not vengeance.” Wiesenthal tracked offenders from his office in Vienna, assembled dossiers on those he suspected to be be criminals, which he then offered to police departments or the media.

Among the many Nazis captured with the help of Wiesenthal’s dogged research was Adolf Eichmann, one of the primary architects of the Holocaust. Though critics say Wiesenthal embellished his role in Eichmann's capture, he maintained that he tracked the fugitive former Nazi leader to Argentina and that his intervention prevented Eichmann’s wife from being able to declare her husband legally dead. Eichmann’s 1960 capture was just the sort of action-packed operation you could imagine seeing in Hunters – he was kidnapped by Mossad agents, held in safe houses while his identity was confirmed, and smuggled to Israel to face trial. Eichmann was convicted of war crimes and executed in 1962.

Wiesenthal’s work also lead to the identification of Gestapo officer Karl Silberbauer. He may not be as infamous as Eichmann, but he too played a hideous role in history: Silberbauer was the officer who arrested Anne Frank. Holocaust deniers were rejecting the veracity of Frank’s diary, and Wiesenthal tracked the man who arrested her family to produce proof of her existence. Upon his apprehension, Silberbauer vividly described finding the Franks in the Amsterdam annex where they had been in hiding, offering further confirmation of her diary. (Silberbauer faced only a disciplinary hearing, not a criminal trial, for his actions. He was cleared and permitted to live out the rest of his days as a Vienna police officer and West German spy.)

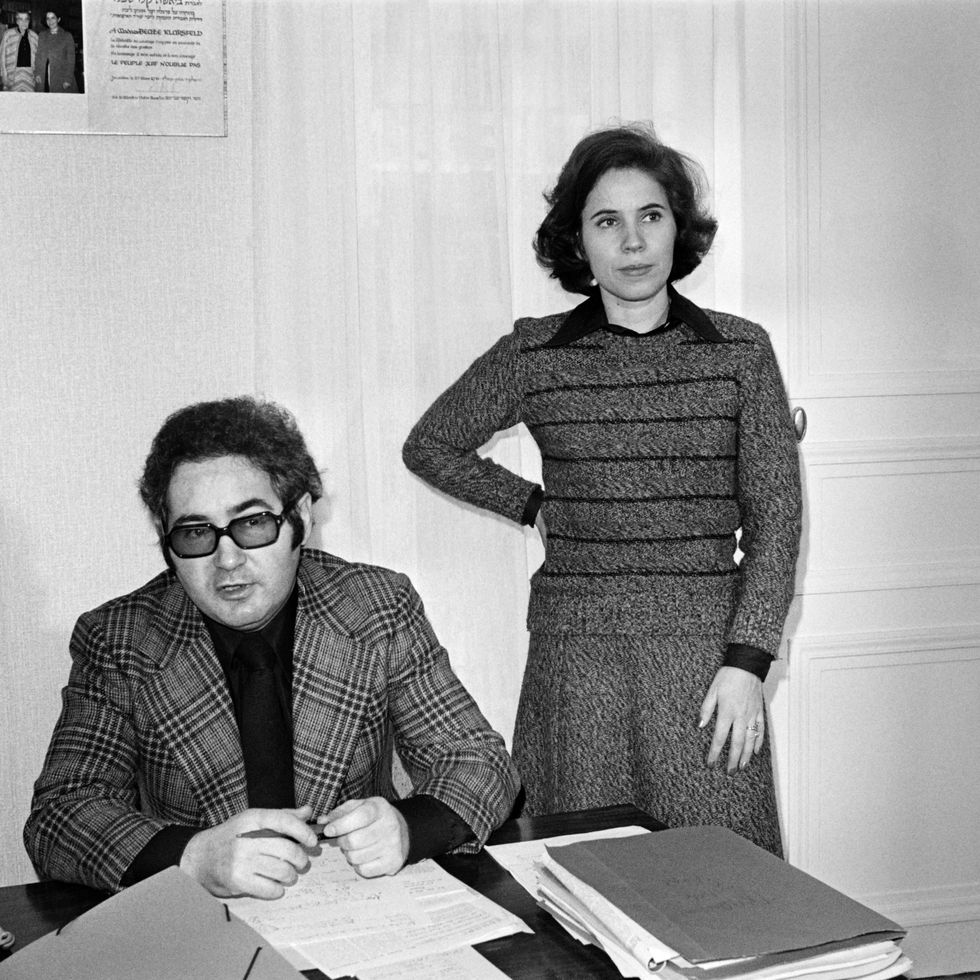

Other Nazi hunters whose exploits may have informed Hunters include Beate and Serge Klarsfeld, who have often focused their attention on the Holocaust in Serge’s native France. As an eight year old, Serge, who is Jewish, was concealed in a hidden compartment of his home’s closet when his father was kidnapped by Vichy authorities and taken to Auschwitz, where he died.

"I was supposed to have been on the same deportation,” he told the Financial Times in 2018. "I wasn’t, thanks to my father. I had the feeling of having this supplementary life. I had to use it.”

Beate is from a German Protestant family, and her parents had voted for Hitler. But after meeting and marrying in the Sixties, the two teamed up to bring Nazis to justice.

They didn’t shy away from public confrontation. In 1968, furious that Kurt Georg Kiesinger, who’d once served as one of Hitler’s propaganda directors, had risen to the German chancellorship, Beate rushed him during an event and slapped him in the face. She earned a four month suspended sentence for the slap, but her attack was successful in raising awareness of his Nazi past, and Kieseinger’s party lost power in the following year’s election.

Their highest profile victory was the capture of former Gestapo leader Klaus Barbie, who was known as the "Butcher of Lyon" for the tortures he inflicted upon prisoners. After their research identified Barbie living in Bolivia under an assumed name, he was extradited to France and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1987.

In 2018, Serge Klarsfeld was awarded the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, France’s highest honour, while Beate received the National Order of Merit. Simon Wiesenthal died at the age of 96 in 2005. But his legacy lives on in the work of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, an NGO that researches the Holocaust and operates Museums of Tolerance in both Los Angeles and Jerusalem.

In a 1964 New York Times article, Wiesenthal told of an encounter with one of his former fellow concentration camp detainees, who worked as a jeweller. The man asked him why he had not continued his lucrative work in architecture after the end of the war. "When we come to the other world and meet the millions of Jews who died in the camps and they ask us, 'What have you done?,' there will be many answers,” Wiesenthal replied. "You will say, 'I became a jeweller', another will say, I have smuggled coffee and American cigarettes,' another will say, 'I built houses,' but I will say, 'I didn't forget you.’"

Gabrielle Bruney is a writer and editor for Esquire, where she focuses on politics and culture. She's based (and born and raised) in Brooklyn, New York.