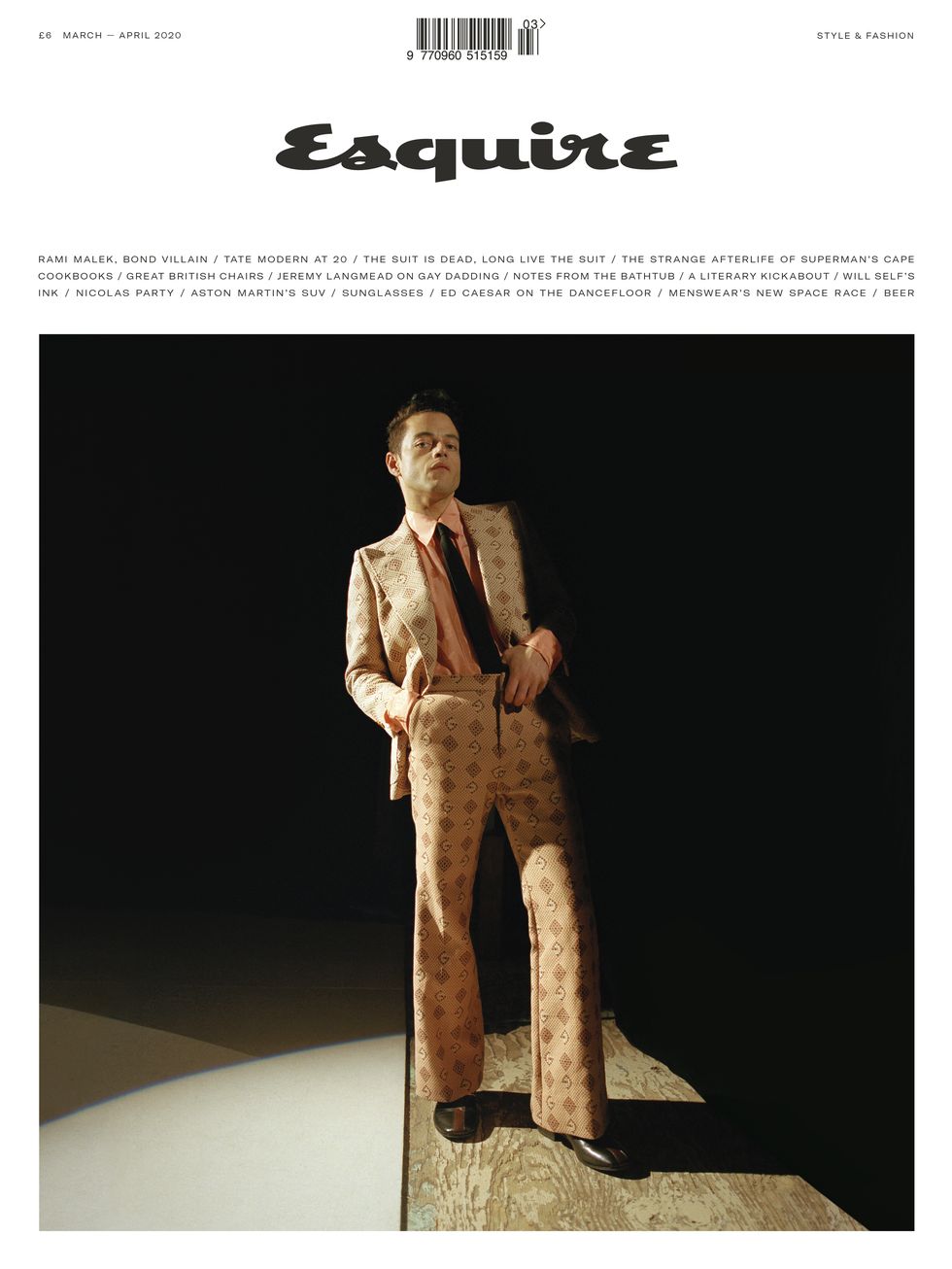

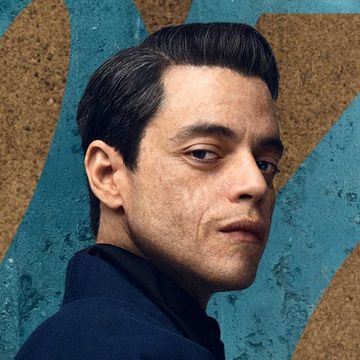

If there’s one thing we know about 007, it’s that he always gets his man. His target this time: Rami Malek, the 38-year-old star of long-running Amazon Prime series Mr Robot, who knocked the entertainment industry’s socks off with his extraordinarily committed — and uncanny — performance as the late Queen frontman Freddie Mercury in the 2018 biopic Bohemian Rhapsody.

“Even before Bohemian Rhapsody he had a very, very good reputation,” says Daniel Craig, veteran of five Bond films including the forthcoming No Time to Die, which will be released in April. Along with the other Bond powers that be, including long-time producers Barbara Broccoli and Michael G Wilson, and No Time to Die director Cary Joji Fukunaga, Craig was on the hunt for a new villain to take on in his final outing as the world’s most high-profile secret agent. “When it came down to casting this part, you have a wish-list of people you want to play it, and he was at the top of the list,” Craig tells me. “We lucked out. He was free.”

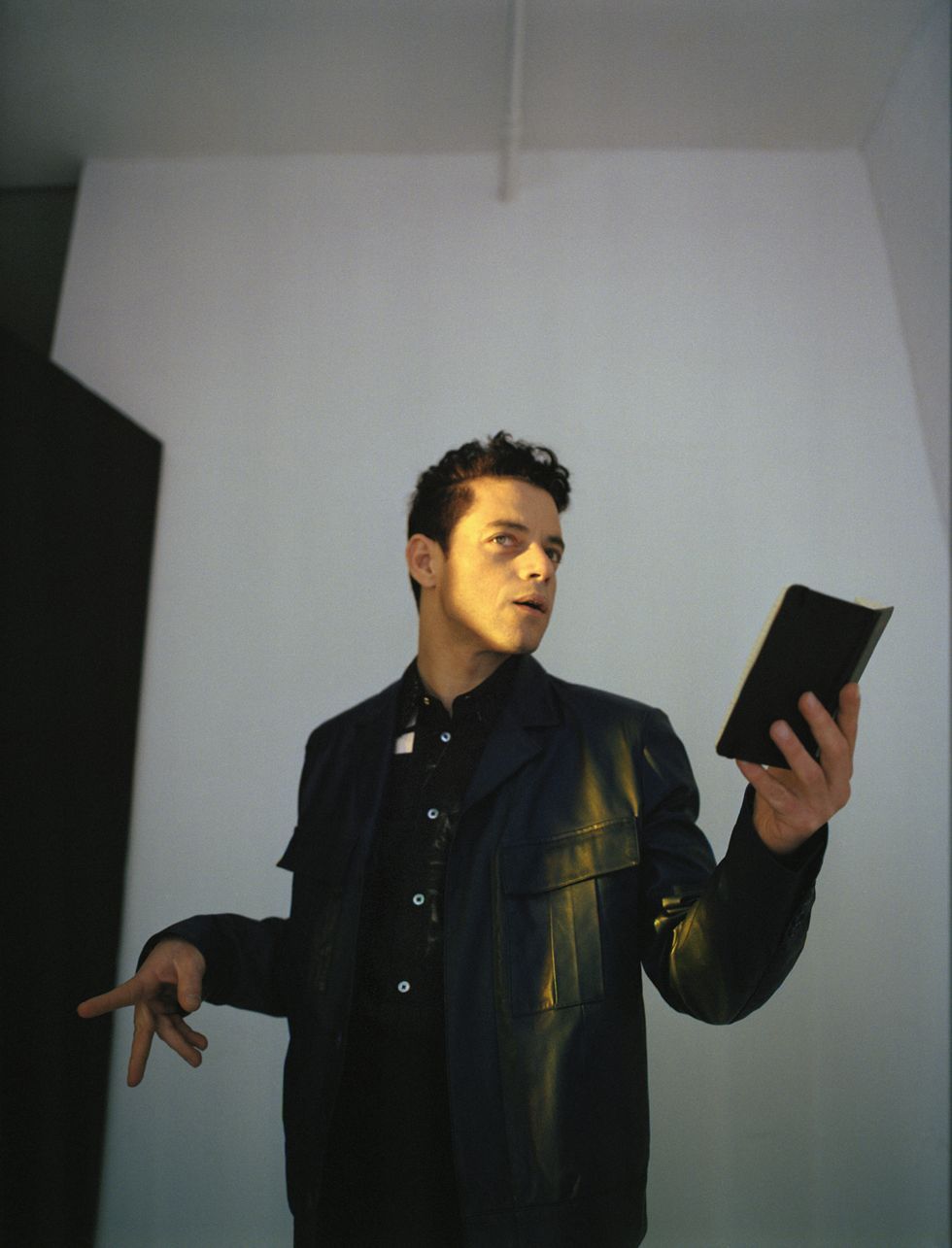

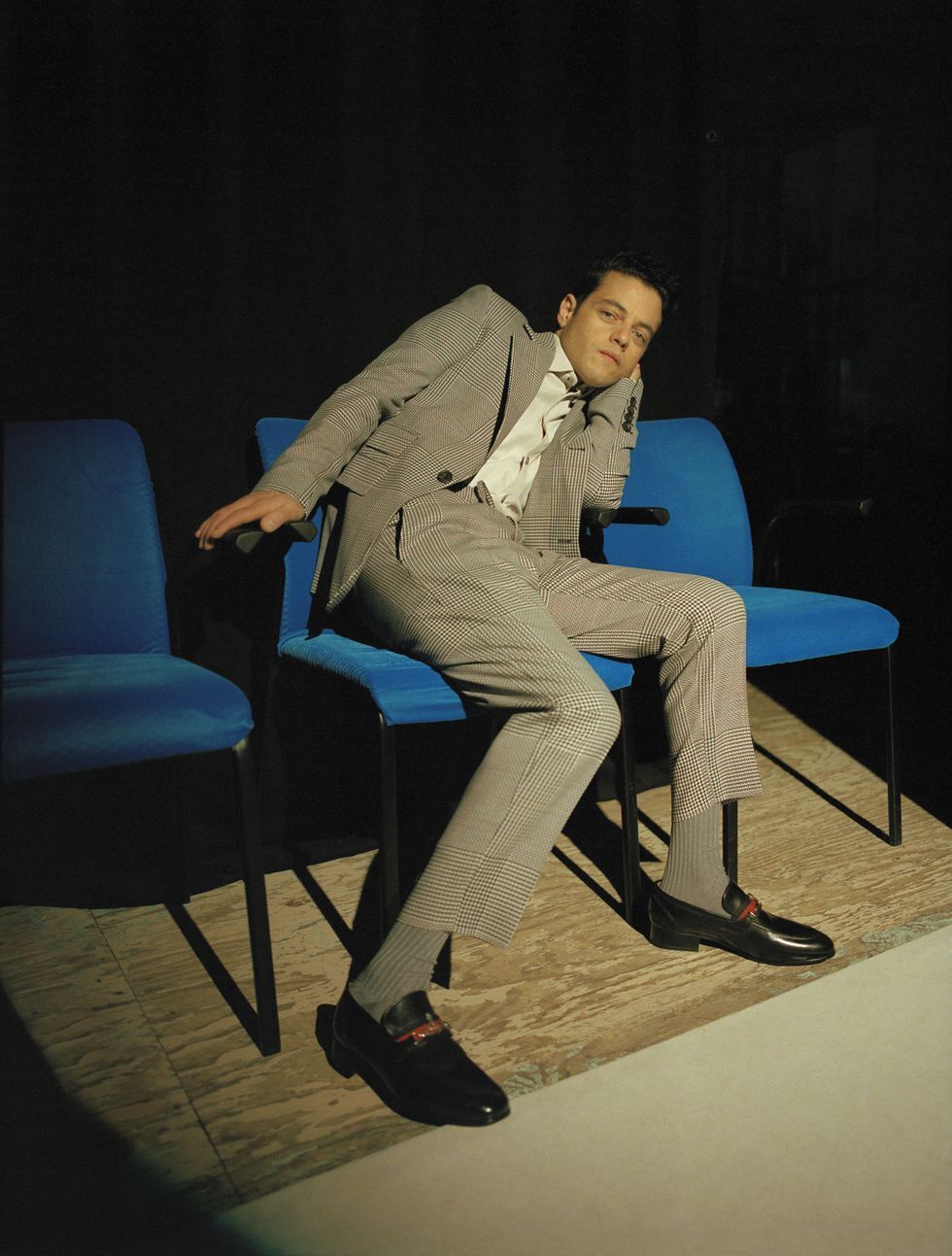

Malek himself wasn’t exactly under the radar — “He’d just won an Oscar,” as Craig points out — and it is easy to see the villainous potential in him. Apart from his reputation as a captivating actor, he has a remarkably versatile face: when he lowers his eyelids, his large, blue eyes look sleepy and cold; if he hollows his cheeks, his jaw juts and his cheekbones pop; he has a low, sonorous voice that he can flatten to a sinister monotone. (The cheekbones and jawline combo comes in handy at other times, too: Malek is currently the face of Saint Laurent’s SS ’20 menswear campaign.)

But nor was he, in fact, free: he was shooting the fourth and final season of Mr Robot in New York. Dates were jiggled, then re-jiggled, then re-jiggled again, until finally a couple of weeks were found right at the end of the Bond production schedule during which Malek could come to Pinewood Studios, just west of London, and film the bulk of his scenes.

“When someone tells me something’s a possibility, I just start to think, ‘Let’s make it work’,” says Malek, who is engaging and cheery in person, his eyes widening boyishly (because — whaddyaknow! — they can do that too). “I kind of just get laser-focused on it, especially when it excites me.”

It’s late December, and Malek and I are sitting in the lounge of a tastefully expensive hotel in Tribeca, New York, as inconsequential flurries of snow fall outside. (Well, to be precise, we sit in the lounge until about an hour into our interview, when a mysterious blonde with a beret and a small dog comes and sits opposite us, uncomfortably close. A hotel guest? An avid fan? An agent of Spectre? We relocate to a table in the conservatory, just in case.)

Dressed in what he describes as his staple outfit — neat navy sweater over a white shirt plus dark trousers and black boots — Malek is talking about the logistics of doing the new Bond film because, although his presence in No Time to Die is a significant reason for the timing of our interview, he also can’t really talk about it very much. So huge is the franchise — to give an idea of how huge, in October last year, The Telegraph described “James Bond and the UK’s booming film industry” as appearing to have “rescued the economy from a pre-Brexit recession” — and so well controlled its machinations, that it’s not worth any participant’s while to spill more details than they should.

“I have to be extremely careful,” says Malek, on his turn as the so-far-so-mysterious Safin. “I can’t really talk about the character.” He also can’t confirm whether he’s signed on for two films, as has been rumoured, or what it was that he came up with during a read-through that prompted Daniel Craig to kiss him — an anecdote that the pair have been testing out on American talk shows. Nor can he describe the outcome of the discussions with Fleabag writer Phoebe Waller-Bridge, brought in to help with the script and work out how an enlightened, “21st-century Bond” might react to certain plot predicaments. “You’ll end up seeing that in the film,” he’ll say with a not unapologetic shrug.

The week before we meet, there had been a press junket for the cast here in New York, including Malek, Craig, the French actress Léa Seydoux who reprises her role as Madeleine Swann, and British Bond newcomer Lashana Lynch, who plays Nomi, a rival “00” spy. A whole junket dedicated to not talking about the thing you’re there to talk about. It sounds taxing. Malek came up with a parrying strategy. “I often asked the journalists, ‘Do you really want to know? It will spoil the film for you, and it’s such an extraordinary event, in it being the 25th instalment and Daniel’s final one.’ I said, ‘Do you really want me to ruin this for you?’”

Well, no. But also, maybe a little bit yes. So we’ll return to Bond later. But first, a little on Malek.

For starters, it’s pronounced “Rah-mi”, not “Rammy”, though confusingly he has an identical twin brother, Sami, now a teacher, whose name is pronounced “Sammy”, not “Sah-mi”. They grew up in California, in the San Fernando Valley, with Hollywood far from their spiritual, if not quite their physical, horizons. His parents, father Said, who sold insurance, and mother Nelly, an accountant, were born in Egypt and had “very, very humble upbringings”, according to Malek; they moved to California in the Seventies, just after the twins’ older sister, Jasmine, who is now a doctor, was born.

There wasn’t a history of performing in the family, but Said, who died in 2006, was “one of the best storytellers,” says Malek. “After dinner you’d almost gravitate towards him because you knew something good was coming, especially if he had at least two of us there, and if it was all three kids… he was gifted to say the least.” Said also furnished the children with an education in classic movies and literature, from (conveniently enough) the novels of Ian Fleming to the plays of Arthur Miller: “I don’t know, maybe it was this idea of the American life that I was adjusting to that was so profoundly rooted in those Miller plays,” says Malek. It sounds, I say, like a highbrow household. “Now let’s not forget,” he replies, “that I’ve probably seen every episode of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.”

Malek describes himself at school as “extremely shy” but also something of “a hustler”. Like the time in elementary school when a new reading initiative was announced: “If you read a book you got a gift certificate to Pizza Hut or something. My brother and I got our dad’s tape recorder and we would read the books on tape and sell them to the other kids so they could not only get the scores they needed but also cash in on some free pizza.” So they… invented audiobooks? He laughs. “We saw an opportunity and we took it,” he says. “I was a pretty resourceful kid.”

He went on to study theatre at the University of Evansville in Indiana, which his parents only permitted him to do after some mild deception: “I had to convince them that it was a liberal arts school and I would be getting a serious collegiate education with a bit of a focus on acting. It was quite the opposite.” As part of his course he even spent a term at Harlaxton College in Grantham, Lincolnshire. “Birthplace of Margaret Thatcher and where Isaac Newton went to school,” he leans into my Dictaphone to note, though when he landed in London and explained where he’d be living, he remembers the passport control official telling him, “Welcome to the armpit of England”.

It did, perhaps, kickstart a recurring interest in the quirks of Englishness. He now divides his time between New York and London. His girlfriend Lucy Boynton, whom he met on Bohemian Rhapsody — she played Freddie Mercury’s girlfriend and confidante, Mary Austin — is from south London. He speaks of his fondness for Sunday roasts (“the gathering of all your friends, not specifically the meat and the gravy”); he demurs from using the American term “wife-beater” when describing Mercury’s Live Aid get-up (“That’s horrid. I prefer ‘singlet’”); he points at his thigh: “I don’t call these ‘pants’ anymore. It sounds ridiculous after being in London. They’re trousers. I’ve been re-tuned.”

He did a stint of theatre in New York after college. Back in LA, he got some decent TV work alongside little parts in big, fun movies (the Night at the Museum trilogy), little parts in big, interesting movies (Philip Seymour Hoffman’s son-in-law in The Master), little parts in little, interesting movies (the acclaimed indie Short Term 12), and little parts in not-so-good-but-still-huge movies (an Egyptian vampire in The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn — Part 2).

Another example of a Rami Malek hustle: when he was auditioning for Paul Thomas Anderson for The Master, he realised that, despite his rapport with lead actor Joaquin Phoenix, the director was still unsure. As he remembers it, Anderson told him, “I just don’t know if this is going to work out. Maybe on the next one.” To which Malek replied, “Paul, you make a movie every seven years. I can’t wait for the next one.” Anderson laughed and gave him the part.

In 2014, he got a call about a new TV series, Mr Robot, that would decisively shift him out of the “little parts” bracket. The show’s central character was Elliot Alderson, a brilliant computer engineer with complicated mental health problems and a drug dependency whose sideline as a vigilante hacker gets him pulled into a world of twisted corporate conspiracy. A plum part that, it turned out, was not easy to fill.

“I think that we’d had over a month of auditioning people,” says Sam Esmail, creator of Mr Robot. “We probably did over 100. Rami came in at the tail-end. I could tell he was a little nervous, and we had him audition with this monologue that was essentially a two-page rant about society. Up until then I was ready to rewrite the script because the rant always came off to me very obnoxious; I started to feel a bit unsympathetic towards the character. Somehow when Rami performed it, it came from this incredibly vulnerable, painful place. Even though he was angry and ranting, he was able to show the layer of pain underneath that the anger was covering up for, and that was when I really started to see the character come alive.”

Esmail describes Malek as “incredibly meticulous; he loves detail, which I think is the crux of a great performance”. (Sure enough, Malek’s turn as Alderson saw him declared “Outstanding Lead Actor” at the 2016 Emmy Awards.) “His work ethic is undeniable,” Esmail continues. “He’s constantly full of energy and looking for that one other little thing that could add more intrigue or depth to what we’re doing.”

Is that always welcome on set? Esmail laughs: “The problem is he and I are very much alike, we get too giddy for our own good when we’re really driving on a scene and we want to keep going and going. But I wouldn’t necessarily consider that a flaw. We’re not there to be the realistic pragmatists; we have other people for that.”

It was, perhaps surprisingly, Mr Robot that led the producers of Bohemian Rhapsody to get in touch with Malek about playing Freddie Mercury. The biopic had first been announced in 2010 with Sacha Baron Cohen in the lead role, but he left the project in 2013 over creative differences with the surviving members of Queen. Elliot and Freddie, I point out, somewhat stupidly, are such different characters.

“Oh, I’m very aware!” says Malek. “What they were thinking was beyond me, but they’d been searching over the course of eight to 10 years and I had possibly honed in on what wasn’t working. I think there’s a sensitivity that they might have seen. A vulnerability that they were aware of in Freddie’s nature. I don’t know, at a base level, I think they were thinking that if he can act, maybe he has a shot.”

Malek went to great lengths to secure the part and get the film off the ground, flying himself to London to get physical and vocal training, practising nightly with a set of protruding false teeth to mimic Mercury’s distinctive overbite, making tapes of himself in character to circulate among the studio executives to encourage them to cough up.

Such thoroughness is a typical trait of his, “to my detriment”, he admits. “I’m a firm believer in leaving no stone unturned. I find it very difficult to leave things in other people’s hands if I feel like anyone may be asleep at the wheel.”

An earlier example of Malek’s thoroughness: when he received a note from Tom Hanks, whose HBO miniseries The Pacific he had appeared in, written on one of the typewriters of which Hanks is a dedicated collector, Malek bought himself a typewriter of his own in order to respond. A current example: while interviewing him, Malek makes it clear that he’s read several recent pieces I’d written because, he says, “I want to know who I’m talking to”. This, I can assure you, basically never happens.

Even when it was finally green-lit, Bohemian Rhapsody turned out to be a notoriously troubled production. Director Bryan Singer was fired while the film was still shooting, in December 2017. Dexter Fletcher was brought in to finish directing it.

After Singer’s departure, Malek found himself in an unexpected position as de facto figurehead of the potentially foundering ship. To a certain extent, it was up to him to right it. “There is something in me that I marshalled in those moments that I’m extremely proud of,” he says. “I wish I could have that same type of courage and confidence in every aspect of my life, but when the shit hits the fan, to be able to find some part of you that you had hoped existed was profoundly moving and hopeful. I think a lot of us had that, and it made me quite proud of the nature of humans I was working with.”

For all its problems, Bohemian Rhapsody went on to be a huge success, grossing $904m (£695m) worldwide and becoming the most successful music biopic ever. Malek’s extraordinary performance — “all glitter and muscle and nerve endings”, as Time magazine described it — earned him the Best Actor Oscar at the 2019 Academy Awards. He is the first actor of Arab heritage to win that award. Immediately afterwards, he got a hug from previous winner Gary Oldman. “I remember him being surprised I was American. That was quite satisfying. Someone you’d watched your whole life give the most iconic, perfect performances.” When we meet he’s a month away from the 2020 Golden Globe Awards, for which he’s been nominated for Mr Robot for the third time, though he says he’s equanimous about winning: “In terms of accolades, I’m quite happy. I’d consider myself a prick if I wanted anything more.” (Which is just as well: Best Actor in a Television Series gong goes to Brian Cox for Succession.)

Malek’s experience on Bohemian Rhapsody, something he went into “with what I would call a maximum amount of trepidation”, and from which he emerged triumphant, was helpful for the film that was about to come. “In a way that armoured me for something like this, and gave me a certain amount of confidence that I felt could protect me throughout the shoot. I think it removed the anxiety that one would have in taking on something so grand.”

Which brings us back to Bond. Who, of course, we’ve been expecting.

The 25th official James Bond movie, and the final one to star Daniel Craig — arguably the most successful of the six men to have played the part, certainly the most successful in terms of box office receipts — No Time to Die has not had quite as fraught a production process as Bohemian Rhapsody. But it has, along the way, also lost a director — Danny Boyle, who left the project after six months in August 2018 — and suffered more than its share of mishaps. Shooting was delayed in May 2019 because Daniel Craig needed ankle surgery after an accident during filming in Jamaica, and then again in June when a controlled explosion at Pinewood Studios proved to be less controlled than planned.

The pressure, not least on Craig himself, is intense to produce a film that not only measures up to earlier successes, but exceeds them. It’s five years since the previous movie, Spectre, and eight since Skyfall, which is to date the most successful of all time, earning more than $1bn (£768m). Both of those were directed by Sam Mendes, a tough act to follow. The casting of the baddie is crucial, of course, and Malek joins a long line of mostly terrific actors — recently Javier Bardem and Christoph Waltz — competing to out-evil the magnificent Donald Pleasence as the MI6 man’s greatest ever, and most fun to parody, nemesis.

Because Malek joined so late into the production of No Time to Die, there was no time for rehearsal. Malek had to head straight to set. “They were under time pressure,” he remembers. “I don’t know how much they loved the idea of fresh Rami coming in… Well, not so fresh, I was just finished on Mr Robot, but at the same time I’d been thinking about this all along.”

Craig, for one, seems to have been impressed. “I have a responsibility on these films,” he says. “All I want to do is make him feel as comfortable as it’s possible to be, for him to feel like he’s welcome, because it’s a huge machine and I don’t want it to feel overwhelming. There aren’t many films bigger than Bond, so I want to make sure that when someone like Rami walks onto set, he can hit the ground running. But he was ready. He was ready to go.”

Of his interactions with Craig, Malek says, “I pushed as much as possible without being too much of a nuisance to ensure that we were doing as best as we possibly could to make it a real fierce one-on-one between the two of us.” He describes their work together as “mutually respectful” and also “philosophically aggressive”.

I ask Craig if he knows what Malek means by that. He laughs and says, “No!” (I think I have a rough idea: when, for example, I asked Craig for his first impressions of Malek as a human being he replied, amused and incredulous, “What, as opposed to a goat?”)

Viewers of the film’s official trailer — 13m and counting — will notice that Malek’s character, who first appears from an aerial view, prowling through a snowy Norwegian woodland wielding a Czech vz.58 assault rifle, has an indeterminate accent, considerable scarring on his face (very Donald Pleasence, that), and a penchant for Japanese masks. Keen beans have noted that his hands are not visible at any point in the trailer, almost as though they had been, say, cut off by the leaders of a Chinese tong and replaced with metal ones. Those masks, by the way, are called Noh masks. And the film, just to remind you, is called No Time to Die.

I figure I may as well ask him, even though we both know what he’s going to say. Is he actually Dr No, the villain played by Joseph Wiseman in the very first James Bond movie, from 1962?

“I heard that,” he says, perfectly pleasantly. “Am I? I mean, isn’t that an exciting thing to consider all the way up to the release?” He does, however, acknowledge that “there is a resurgence of an Ian Fleming influence on this film”.

Craig will go only so far as to say of Malek’s turn, “He’s a very complex human being, he played a very complex part, and it was just fabulous to watch.” (For my money, if Malek doesn’t turn out to be Dr No, I’ll eat Oddjob’s hat.)

Sam Esmail, with whom Malek has a couple of feature films in development — the final episode of Mr Robot aired in December — is excited to see what Malek brings to Bond. “Watching the trailer, I’ve got my own expectations of what his part is going to be and how he’s going to perform it,” Esmail says. “But this is the one thing I definitely know going into it: all of those expectations are going to be subverted. He’s going to surprise me in a very interesting and compelling way. I know it’s going to be really special.”

Malek hasn’t seen No Time to Die yet and is toying with the idea of waiting until it premieres in London at the Royal Albert Hall. He plans to take the next two months off — off-off — and finish a writing project he’s been working on. “I quite like the idea of sitting with everyone else and watching their reactions for the first time and having my own.” He hesitates, “Having said that, it would be a little too late to weigh in on anything.” Then he smiles as, for once, he gives himself up to the higher powers: “With something of this scale and scope, I don’t know how much you have in the first place.”

Before he heads back into the not-so-snowy streets of New York to meet his girlfriend for dinner, I ask Malek if, given the significance of this being not only a Bond film, but an end-of-era Bond film, he felt under pressure to make sure he was giving Craig the very best of send-offs.

“I mean, of course,” he says, “but I’m going into this…” He pauses. “It’s Bond! I’m going to do my absolute best.”

And he looks at me with those large, blue eyes, struggling to compute how he could ever do anything else.

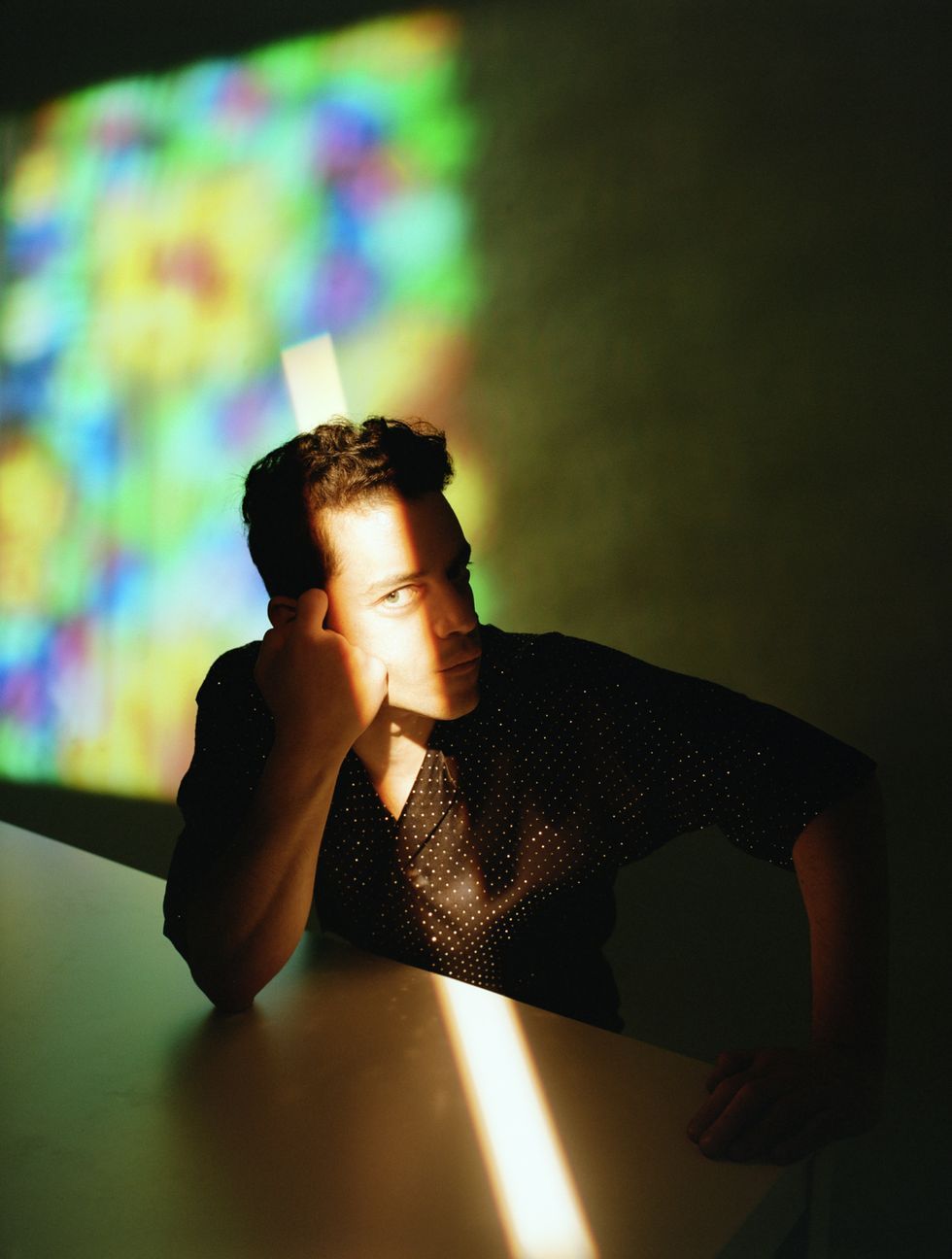

Styling: James Sleaford | Styling assistant: Rachel Clark

Photographer: Dexter Navy | Assistants: Tyrell Hampton; James Mulroy; John Temones

Hair and makeup: Kumi Craig

Miranda Collinge is the Deputy Editor of Esquire, overseeing editorial commissioning for the brand. With a background in arts and entertainment journalism, she also writes widely herself, on topics ranging from Instagram fish to psychedelic supper clubs, and has written numerous cover profiles for the magazine including Cillian Murphy, Rami Malek and Tom Hardy.