When we think of auteurs working in cinema today, Paul Thomas Anderson’s name is likely to be near the top of any list. And rightly so. There’s a PTA film for everybody. Maybe you’re a sucker for the goofy romance of the Adam Sandler-starring Punch-Drunk Love. Maybe you like to shout ‘I drink your milkshake!’ or ‘I’ve abandoned my child!’ along with Daniel Day-Lewis in the masterful There Will Be Blood. Or, maybe, last year’s Oscar-bothering Liquorice Pizza is your jam.

But, from the San Fernando Valley to the oil fields of New Mexico, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone willing to go to bat for PTA’s sixth feature, The Master, which celebrates its ten year anniversary this month. Starring Joaquin Phoenix as damaged WW2 veteran Freddie Quell and the late Philip Seymour Hoffman as the exploitative cult leader Lancaster Dodd, The Master is a slow and ponderous film, but also one that is beautifully shot, intelligent, smartly-costumed, and contains career-best performances from more than one of its leads.

Let’s start with the cast. Alongside Phoenix and Hoffman, we have Amy Adams as Hoffman’s wife, a powerful undercurrent keeping these wayward men in check with forceful guidance and sexual favours (definitely file this under ‘career best’). From The Power of The Dog to Judas And The Black Messiah, Jesse Plemons’s involvement in a film is more or less a guarantee of quality these days. Here, as Hoffman’s conflicted son, he gives us a lot with few lines to play with. Add to that Laura Dern and Jillian Bell as cult members, and Rami Malek as Hoffman’s subservient son-in-law, and you’re looking at one of the best casts ever assembled, with (as of 2022) 19 Academy Award nominations between them.

It is, however, Phoenix’s film. The Master was his comeback after the polarising documentary I’m Still Here, in which he pretended to quit acting to pursue a rap career (a production marred by on-set sexual harassment allegations against director Casey Affleck). Phoenix could not have picked a better role. We’re introduced to Phoenix’s Freddie as American GI’s goof-off on an unnamed Pacific beach. Freddie watches from afar while the men wrestle. Then, he pretends to hump a woman made of sand, continuing long after the GIs cease laughing. The next shot shows Freddie – stick thin and hunched – masturbating in broad daylight, facing out to sea. Five minutes in, and watching Freddie is excruciating.

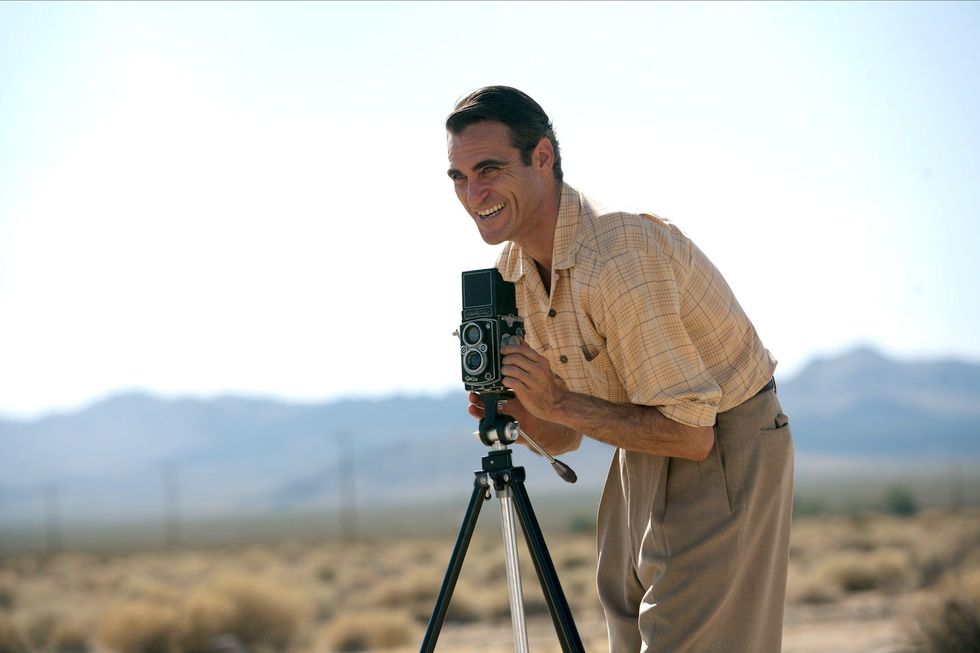

After the war, Freddie is admitted to a psychiatric ward, before taking a job as a department store photographer and, when he is fired for starting a fight with a customer, picks cabbages, before being run off after possibly killing one of the older workers with homemade alcohol.

His performance earned Phoenix his last Oscar nomination before his win for Joker seven years later. And, in Freddie’s awkward, sexually-obsessed, physically twisted and pained performance, we see a forerunner of Arthur Fleck. (Arguably an even better performance).

The rest of the film sees Freddie mix and consume concoction after concoction of fuels, fluids and medicines in a bid to sustain his high, and remain divorced from his reality – a past-time that brings him into the orbit of the bullying, domineering Master (Hoffman), an absurd, Hemingway-esque brute. Hoffman is also at his career-best here, his Master describing himself as a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist, a scientist, a connoisseur, and above all, a man (Damn it!). Spurious bullshit from start to finish.

Freddie is quickly subsumed into the Master’s orbit and they travel from New York to Philadelphia to Arizona and eventually, England together, recruiting the gullible and desperate into a cult that seeks (in a detractor’s words) to use “time travel hypnosis therapy” to bring about world peace and cure cancer. “Leave your worries for a while, they’ll be here when you get back. Your memories aren’t invited,” he tells a reverential Freddie.

In our modern world of reality TV presidents, untrained Instagram influencers touting wellness, and an increasing scepticism of expertise and science in any form, The Master’s personality cult is shockingly prescient. Were Lancaster Dodd alive (and real) today, he’d certainly be expounding on the dangers of vaccines, the evidence for a flat earth, and taking DMT with Joe Rogan on the reg.

Where The Master really stands out is in its cinematography. The Master was the first film to be shot on 65 mm film since Kenneth Branagh's Hamlet in 1996. In another first, Anderson swapped his regular cinematographer Robert Elswit for Mihai Mălaimare Jr (Jojo Rabbit, The Harder They Fall). The result is spectacular. In the opening scene, the blues of the Pacific Ocean billow behind a GI transport. Then, we see Freddie’s GI helmet, and can almost feel the texture of the rough metal.

When Freddie goes to work in the cabbage fields, it’s like watching a Steinbeck novel brought to life. His night-time escape through empty fields – all fog and long-legged, gangly sprinting – is superb. The Arizona desert, where Freddie and the Master go to dig up a cache of the Master’s life’s work, has the feel of a classic 1950s adventure. From beautiful suits and shirts to classic haircuts, cigars, yachts and motorbikes, this is an incredibly stylish film, elevated to new heights by Mălaimare Jr’s lens.

Ten years on, The Master remains as relevant as ever. It’s a film about paranoia. About exploitation. About PTSD and generational damage. A canvas of America and the American psyche at a certain point in time. Yes, at times it feels like you’re watching an overly-stylised play. Yes, it lacks the easy humour of Boogie Nights or absurdity of Inherent Vice. But as a piece of serious, adult filmmaking focusing on the obsessions and delusions of men, only Anderson’s own There Will Be Blood has come close. This will never become your go-to easy watch. But, like Freddie determinedly riding a Triumph motorbike off into the sunset, it certainly deserves one more chance.