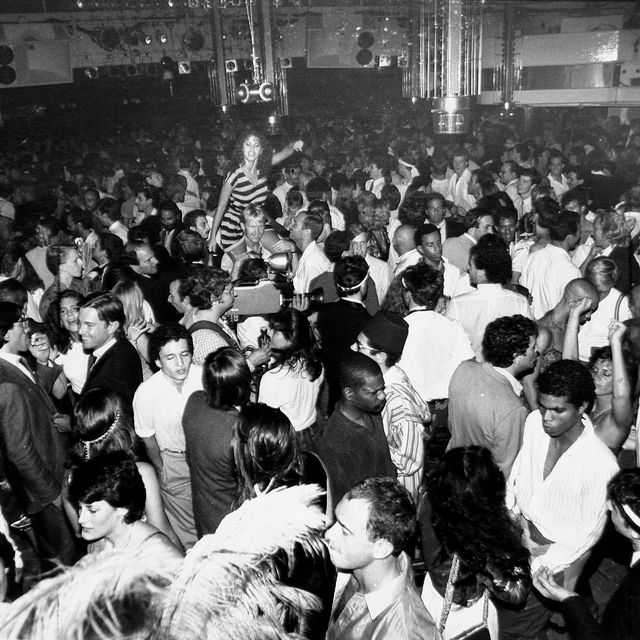

A party in a vast, disused railway depot in Manchester. Heavy rain outside. Nearly 10,000 people within. Light shows piercing pools of darkness. Legions of security guards watching for trouble that never comes. The music beating slower than many racing hearts. Young women in cycling shorts of every shade and skinny young men with their shirts off. Drops of sweat falling onto the crowd from the ceiling girders. And, standing in the middle of the throng, rapt: me.

I wasn’t at a rave, exactly. The night was organised by The Warehouse Project, Mancunian club promoters who have been throwing huge and ambitious parties in the city’s post-industrial caverns since 2006. But the event was definitely rave-like. Whatever you want to call it, you might wonder what business I had spending my Friday night in a railway depot surrounded by kids half my age. I’ve asked myself the same question. I am a man approaching 40 with two small children, a serious job, and an onerous mortgage. The short answer is I have fallen hard for house music, and that if you were to describe this period as a midlife crisis, you might not be entirely wrong. But a crisis betokening what, exactly? That’s the puzzle.

Three summers ago, with my life in some turmoil, I went to Ibiza with my wife and friends. It was my first time to the island. I was enamoured. We ate late, delicious, inordinately expensive lunches, which doubled as breakfast, and pedalled through swift hours in hot night-clubs, writhing among armies of the buff and the nearly naked. Our hangovers were addressed by laying horizontal under green-fringed parasols on the world’s most beautiful beaches, and by eating ice cream. It was bliss.

Just before that trip, my taste in music had expanded exponentially. I’d long dismissed any music that you danced to as inherently boring. If the only purpose of the stuff was to make you move, I thought, how interesting could it be? There was something monstrous about those people you sometimes met — often Dutch guys, I found — who talked excitedly about beats per minute, as if you could engineer emotions by grinding the tempo up or down a notch or two, like you were fixing the transmission on a car.

But now? I wonder why I wasted so much of my life in ignorance. The problem is one of description. “Dance” or “electronic” or “techno” or “house” are about as useful generic catch-alls as “classical”: they contain multitudes. And while there’s plenty of dance music I still find boring, there are large swathes I find as addictive and moving as any music I’ve ever listened to. (There’s a Cuban-American DJ and producer called Maceo Plex, for instance, who I believe might be a genius to rival Miles Davis.) Among the attractions of the music is a conflict at its heart. It’s made in studios, but it’s best experienced live, preferably with some enthusiastic and sweaty strangers.

So that’s why I was in the railway depot. Or, at least, it’s one of the reasons. Headlining the night was Camelphat: a pair of Scousers, Dave Whelan and Mike Di Scala, who have been making music together since 2004, but recently experienced two years of vertiginous success. Their biggest hit has been “Cola”, which sounds like a kind of dissonant version of a Chicago house number from the Eighties. Its lyrics, which were written by Alexander “Elderbrook” Kotz, are unnerving. They appear to be about a girl whose drink has been spiked. “She sips the Coca Cola, she can’t tell the difference yet,” runs the refrain. Millions of people have thrown their hands in the air to “Cola”. The last time I checked, it had been played more than 150m times on Spotify.

Something intriguing, and unsettling, is happening when a track like “Cola” breaks out of clubland and into the mainstream. What’s more,“Cola” sounds like “Hello Sunshine” compared to another of Camelphat’s best-known tracks, a re-mix of Au/Ra’s “Panic Room”. At the warehouse, the crowd’s reception to the opening chords of “Panic Room” was euphoric. The lyrics are terrifying:

“Hell-raising, hair-raising, I’m ready for the worst,

So frightening, face-whitening, fear that you can’t reverse,

My phone has no signal, it’s making my skin crawl, the silence is so loud,

The lights spark and flicker with monsters much bigger than I can control now,

Welcome to the panic room, where all your darkest fears are gonna come for you.”

“Panic Room” is not a track that only wants to make you move, although it also does that. It is pitch black. I’m at a loss to understand its popularity, except to say that I like it very much too. The clash of the words and the roiling, propulsive arrangement, seems like an appropriate response to the complications of our current moment. We get the music we need.

In the depot, such angst was more than balanced by many moments of uncomplicated and giddy fun. You will make many friends in Manchester if you play “Fools Gold” by The Stone Roses in the middle of your set, as Camelphat did. The attraction of the music, and these nights, is in the mixture of emotional colours. It’s like going to an evangelical church: some fire and brimstone, some joyful praise.

This, I recently realised, is the answer the music provides, the crisis it solves — for me, at least. It’s involving, and consuming. It offers you the chance to get outside of yourself. For a few elastic hours, you are released from the roles you spend the rest of your life playing: earner, colleague, husband, father. You become simply a celebrant in a strange ministry.

This piece appeared in the March/April 2020 issue of Esquire. Ed Caesar is an editor-at-large for Esquire and the author of, most recently, The Moth and The Mountain, out now in paperback