In 2015, over Thanksgiving dinner in Taiwan while shooting Silence, Martin Scorsese – or as anyone who's worked with the Oscar-winning director knows him, 'Marty' – told his VFX supervisor, Pablo Helman, that there was a film he’d been mulling over for a while. The trouble was, without the right kind of technology, it couldn’t be done the way he wanted to do it. And Marty (excuse us, Scorsese) movie isn’t going to get made unless it’s made in exactly the way Scorsese wants it to be.

“He’s an encyclopaedia of film,” says Helman. “We started talking about this new technology that we’d begun to look into which could yield a younger actor. He’s a really curious person, so he said, ‘Tell me, more about that.’”

Helman has been with Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) – the visual effects arm of Lucasfilm– for 24 years, starting with Jurassic Park 2, then moving onto the Star Wars franchise and multiple other visual effects-heavy movies. When he told Scorsese his ideas for creating a younger version of an actor, Scorsese said that it would be a project he’d want to be a part of. Helman got a copy of the script of The Irishman that night. By this point, Scorsese had been sitting on the film for about six years. Helman came back to set the next day saying he was in.

“It was the perfect opportunity for visual effects,” he says. "[I’m] always looking for a project that has visuals that support the content all the way.” In other words, there are plenty of VFX-laden stories out there created primarily for spectacle. But for a veteran VFX artist, monsters and superheroes are just the day job. The dream for Helman was a project where the VFX supports the reality-based story. Proving he's not as much of a magician as he seems, the two-time Oscar nominee (third time's a charm) was good enough to reveal how his trick works.

What were Scorsese’s deal-breakers with the technology?

It was clear to me and to Marty that without preserving the performances, we couldn’t do the movie. Marty told me that it was very important for Robert De Niro and all the actors to not have to wear markers on their faces; to not wear a helmet with the little cameras in front; that the process of getting the movie done had to be the way they normally would do it, because they’re method actors. And that sounded like exactly the kind of actor-driven opportunity that [ILM] had been looking for, to bring in this innovative tech with an incredible project.

So this is brand new territory for you, despite having worked on some of the biggest VFX blockbusters of the last three decades?

It is. If you think about what everybody was doing in 2015, they were wearing hundreds of markers on their faces, a helmet cam and grey pyjamas; they’d be in a room not even with their acting partner, just someone standing there for an eye-line. So, for two years, I was allowed to sit down at a table with a bunch of people that are a lot smarter than me and work on this challenge that needed to be solved. We just said, ‘Forget about everything that has been done before. There are no markers here, there is nothing; it’s just the cameras and the actors.’ We had to figure out how to capture that performance and turn it into what we call geometry. The answer to that was the actor standing in space with lighting and texture on their faces.

Explain the technology in the simplest terms, as if we’re not Oscar-nominated VFX whizzes.

There are three cameras on the rig [designed with director of photography Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC, and ARRI Los Angeles, it was nicknamed “The Three-Headed Monster”]. The centre camera is the director camera and to the left and right of it there are two infrared “witness” cameras. On the infrared cameras, there two infrared rings that illuminate the actors. You don’t see the light out of those two cameras since they work on a different light spectrum, but the infrared light normalises the picture so there are no shadows on the actors' faces. Then, the software [called FLUX] takes a look at the images combined from the three cameras and it creates deformation, or geometry that mimics the actor’s performance. It takes a look at one frame and then it renders it, and then takes a look at the next frame and renders it and so on, until it completes the scene.

Because there are no markers to be tracked, the software is a lot more sensitive to the way the skin moves. And because the software is deforming the geometry, it’s a lot more faithful to the actor’s performance. For instance, when the actor is talking and the English phonemes reverberate through his face, the software picks that up really well. And that’s why the dialogue hit in the right places as opposed to doing key frame animation, in which you’re basically making up the way the dialogue is delivered.

So, what happened first?

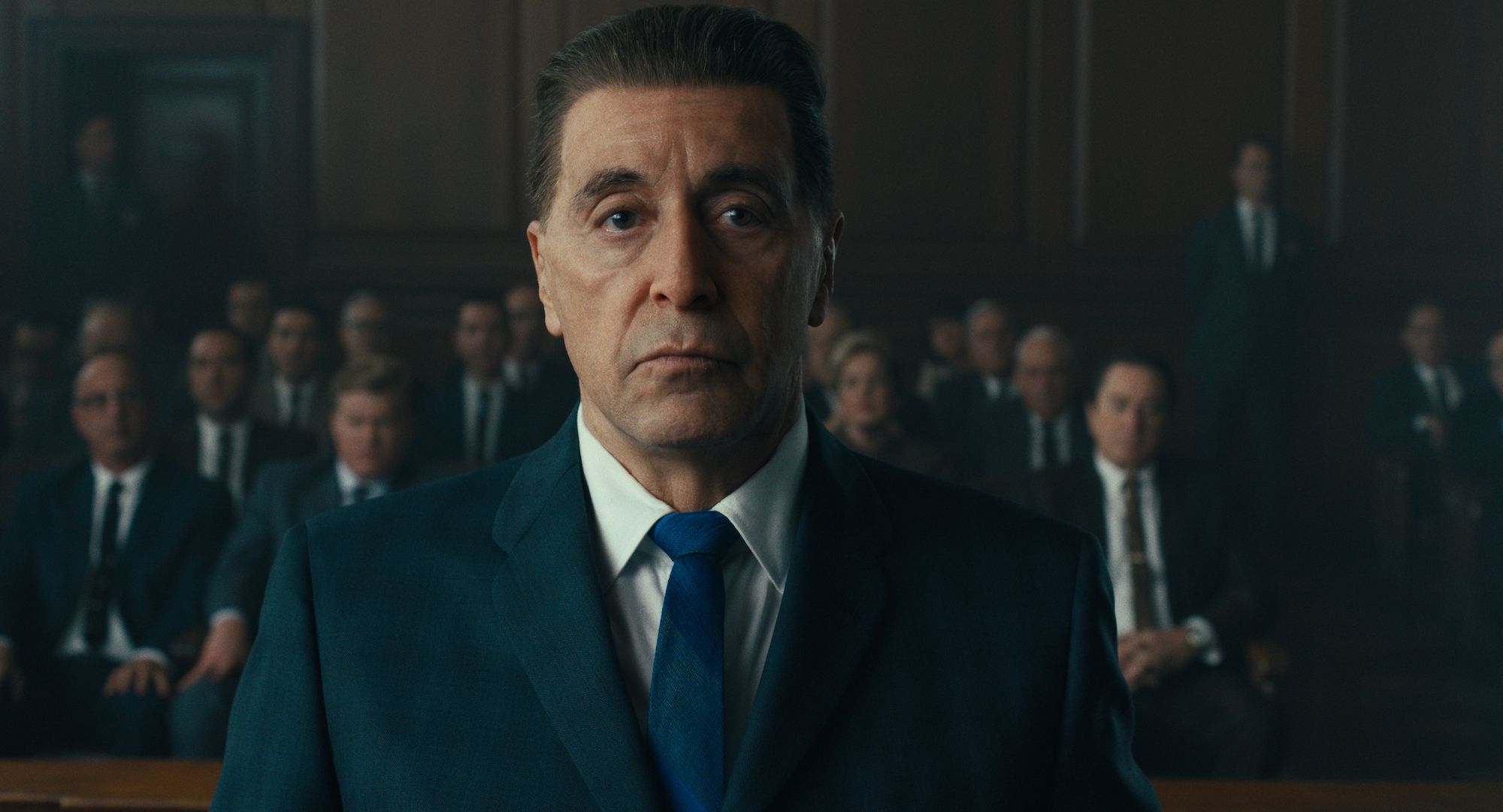

First, we had to prove to Marty that we could do it. I decided to do a test by recreating the scene from Goodfellas – the one with the pink Cadillac, where Robert De Niro is screaming at the top of his lungs – to show that I could make De Niro look like he did back then. So, I found myself writing for Bob De Niro and there he was, swearing in front of the camera and doing everything that was in that scene for about two minutes. And he loved that he didn’t have any markers on his face. We took that scene back to ILM and in ten weeks we turned around about 12 seconds of footage, in which he looked the same as when he was in Goodfellas. We showed the test to Marty and to Bob at the office in New York and they loved it. That was the first time I heard Bob say, ‘Well, you’ve extended my career by 30 years; this is great.’ And the movie got green lit out of that test. Marty was elated.

Along with that elation, was there any part of you that was a bit nervous? If this technology failed to convince the audience and the critics that De Niro and Pacino were 30 years younger, it’d be on you and ILM.

We all knew that it was a big risk. One of the people I consulted in the beginning was Dennis Muren, ASC [who has won nine Oscars for his work with Steven Spielberg, James Cameron and George Lucas]. His office is right next to mine. I went in and put the script on his desk. I told him about this incredible opportunity, and he looked at me and said, ‘This is really risky.’ I asked, ‘Do you remember what you felt like when you did Jurassic Park?’ And then he looked at me and said, ‘Yeah, you’re right; you should do this.’ At ILM, we all keep the same sense of discovery that we had the first day that we started working here. But it was a little like racing the Grand Prix while you’re still building the Ferrari; at some point, you just have to jump into the car.

What were the actors’ reactions to seeing themselves 30 years younger, or to the technology in general?

The first time that Joe Pesci took a look at the camera rig he made a comment about it being really big. He said, ‘You’re putting this in front of me and I don’t even know where to look!’ But little by little they all got used to it. And because the technology was completely separated from them and we were not going to change any of the performances, I think that helped.

Bob was also very interested in the technology and he was always around working with us. He even took a look at the post-production process. We would meet with him and he would take a look at the work and he repeated that same thing again, that I’d given him 30 more years on his career. One day, I asked him, ‘How do you do what you do when you perform?’ Like, he performs with his chin, with his nose. I said, ‘Did you know that you actually move your left and right eyebrow completely separate from each other?’ I asked him if he worked in front of a mirror to do that. And he said ‘No, no. It’s just me.’ He doesn’t talk much, but he was completely into it.