When Margaret Atwood is discussed these days, numbers necessarily lead the way in, to underscore and give full accounting to the Atwood phenomenon: She’s written more than 50 books. These have been translated into more than 25 languages; The Handmaid’s Tale has sold over eight million copies and counting; the Hulu television series based on her 1985 novel has won fourteen Emmy’s and is in its third season. Her latest novel, The Testaments, the long-hoped-for sequel to The Handmaid's Tale, is already in its third printing in only weeks after its release. The first printing? 500,000 copies.

I can’t count the number of interviews she’s given—in print, online, on TV—as part of The Testaments tour. I’m not sure she can either, as they accrue, and if the media’s voracity overwhelms her, she’s not likely to admit it. In public, the author, who’s also my friend from some years of working together on various projects, is a model of self-restraint. That’s not to say she tempers her wit and infamous ink-black humour when she’s on any stage: not in the least, thank goodness, but the personal she saves for personal interactions, and, more vitally for her readers, she saves her real subversion, just how transgressive, deliciously dangerous, even outrageous, she can and needs to be, for the page. And the four hundred and fourteen pages of The Testaments gave Atwood plenty of room for just that.

In interviews she’s explained that she demurred about a follow-up to her best-known work because re-inhabiting the voice of heroine and modern-woman-turned-sex-slave, Offred (as Atwood did on that fateful, Orwell-haunted year of the character’s conception, 1984), was, for her, an impossibility. But she found three points-of-view she could inhabit—two of which are teenagers, Agnes Jemima, born and raised inside the repressive theocracy of Gilead, and Daisy, raised on the outside in the free territory of Canada whose stories Atwood picks up roughly fifteen years after Offred’s account ends. Fans of the novel and the show know Offred has two daughters, one who was snatched from her when she was conscripted as a handmaid and another with whom she was pregnant when she fled Gilead. From Agnes and Daisy’s introduction, the question of who their mother is propels the story, as do the girls’ voices, which are as energetic and earnest, moody and melodramatic as you’d expect from any adolescent. If these sections sometimes read like young adult fiction, and they do, that owes not only to how openly Atwood collaborated with her fans, whose inspiration and insistence on knowing more she notes in her acknowledgements, but because she knows that if human beings (whether real or imagined) are going to transcend the direst of circumstances—from authoritarian regimes to climate crises—it’s the young on whose strength and clarity of purpose we’ll have to rely. Like a sign held up in the recent climate marches, Atwood knows sometimes, “Children are the only adults in the room.”

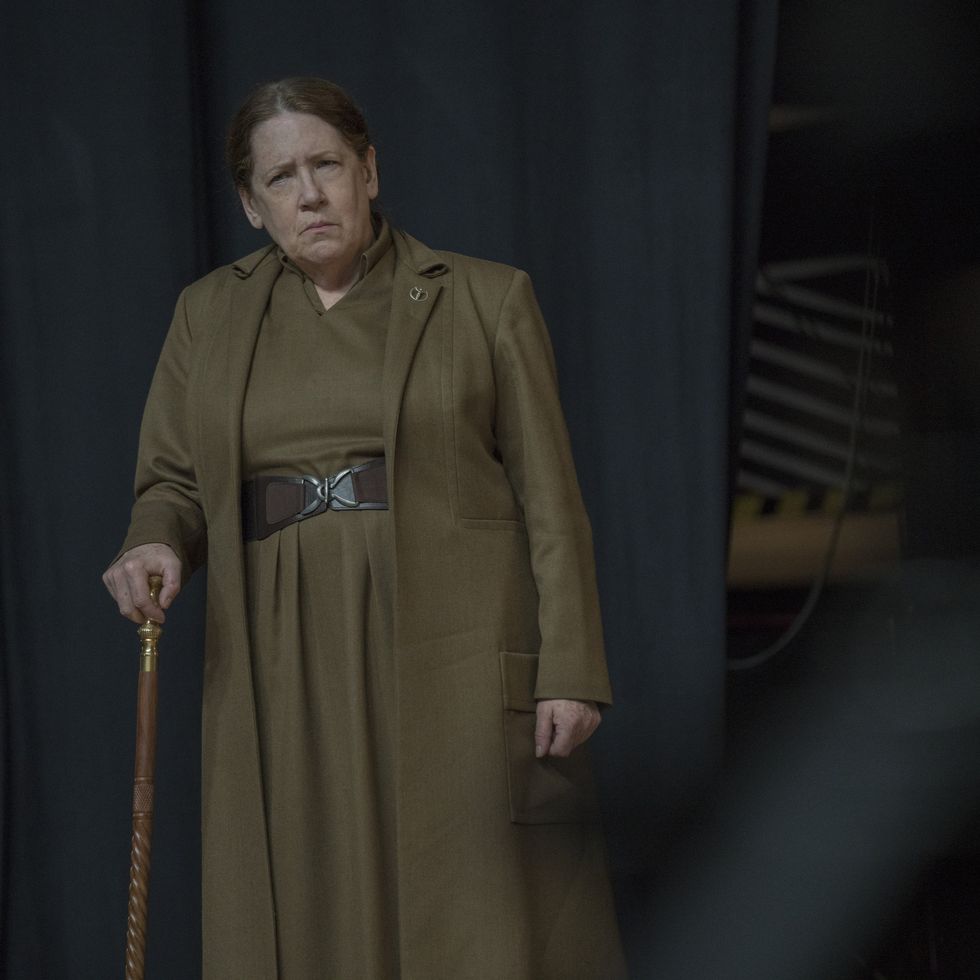

Atwood is certainly expert on adults behaving badly, and that’s where Aunt Lydia comes in. Hers is the sequel’s third point of view. It opens the novel and beguiles for its menace, alive with the contradictions of a woman who’s a player in a power structure that also subordinates her. Via Aunt Lydia we run headlong into some of Atwood’s most enduring preoccupations: uses and abuses of power, human history’s many jags of totalitarianism (these as redundant as they are persistent, especially in depriving women of rights, reproductive and otherwise), and that nothing and no one is as they seem. Certainly not Aunt Lydia. She tells all, providing context for the brutality she’s become conversant in, enforcing Gilead’s perverse norms with the delicacy of branding iron. Atwood delights in upending readers’ expectations—a monster can be a hero and vice versa.

A descendant of the very American Puritans on whose theocracy—at least in part—she based Gilead, she’ll tell you her contrariness is on the gene. That plus her boundless curiosity (she’s as deeply read in history and literature as anyone I’ve met or read) account for how prolific she is. Never mind that she’s tireless: She writes on planes, trains, in hotel rooms, and when we spoke she was on an Amtrak from New York to DC. Her husband of 46 years, novelist Graeme Gibson, passed only days before our conversation, but Margaret had to keep moving, fulfilling her obligations, that is, being Margaret Atwood. Through tunnels and despite conductor announcements, we talked, laughed, even if at moments we both felt like crying. Graeme’s death was foreseen, prepared for as much as any loss of that magnitude can ever be, with friends and family around him, but now Margaret was back traveling at high speed. I thought it best she and I travel back to the beginning then, to 1984, to reorient us in face of disorienting events and trace a solid line back to a woman alone in a room, writing a novel, the novel, looking, as she often is, for trouble.

Amy Grace Loyd: I’d like to start at the beginning of The Handmaid’s Tale, I mean its real beginning. That can get lost in the media frenzy – the act of writing, writing you knew would get into you into trouble – potentially—

Margaret Atwood: You know, Amy, anything you write causes you trouble of one kind or another.

True. And it’s especially true now.

MA: My, yes.

But there you were in 1984, confronted with a German typewriter where none of the letters were in the right place or any place you recognised. All while the East Germans were firing off loud canon-like things to let you know they were there on the other side of the wall and you were taking on the topic of totalitarianism—an act of bravery, wasn’t it?

MA: I’m not easily frightened. An act of bravery means you’re frightened but you do it anyway.

What would you call it then? You often say writing is a form of optimism or hope–that the words will come together into anything cohesive, that anyone will want to read them. Does that apply here? Or?

MA: I think it’s more an act of foolhardiness.

And the trouble you’ve said you were getting yourself into?

MA: I knew the subject and my treatment of it could cause some trouble, but that’s not the kind of trouble that scares me. It interests me. To see what will happen. The things that scare me are pretty simple: They are bears, thunderstorms, and forest fires. This was none of those.

What about the ocean getting warmer? That’s something you’ve raised in your interviews all while supplying your kind of vivid detail—

MA: Do mean the choking?

If the oceans’ temperatures rise, it will kill the marine algae which produces 80 percent of our oxygen, but before that happens you said, on The View—was it?—there will be lots of car accidents because—

MA: Because we’ll all be choking to death. You can’t operate machinery if you can’t breathe.

Funny, Margaret, but scary—

MA: For you, yes, and for others. That is a scary thing on behalf of life on earth. It’s something we should fix and right now, right away, but at my age I’m probably going to die before the oceans warm to that degree. But the ocean getting warmer and more acidic—that’s happening, too—it isn’t as immediate as a bear in pursuit. That’s why it’s taken people so long to grasp this issue. It doesn’t come at you with teeth and claws, but I see by Friday’s climate march in different cities all over the world that they are grasping it now. People have been talking about this for 50 years or more. Or scientists have but most people couldn’t see it. It didn’t affect them. Now they can see: the fires, the rising waters, the hurricanes, they’re here; they’re tangible.

They’re not fake news.

MA: No way.

In the interviews you’ve been giving you said a few times over about The Handmaid’s Tale and now The Testaments that you didn’t make them up, history did. But you synthesised so much history and literature to give us this speculative fiction, this cautionary tale, which came from your interests and from real instincts in you about how history moves and repeats.

MA: It’s all in Madeline Albright’s book Fascism: A Warning. She’s got it all laid out. And there’s Tim Snyder’s On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons From the Twentieth Century, too. Important books. But, yes, it’s personal in that I’m interested in it, though the good news is that I’m not the only one who’s interested in it.

But your interpretations of these phenomena have caught the popular imagination, and the idea in both novels is about testifying through words, writing it down so it will be remembered, shared, understood. Again it’s the act of writing--

MA: I’m a writer. I figured that out young, and writers write. They speculate. Engage ideas. And at that moment in time, in the '80s, I was hearing a lot about what people would like to do if they got into power, and having been born in 1939 and been through WWII and its aftermath when we were all trying to understand what happened, I knew Hitler spelled it all out in the 1920s, in his book, what he would like to do if he got power, and people did not take that seriously. So I believe if someone says they will do certain things, unimaginable things to many, they will in fact do them when they get the power they’re after. That is what you’re seeing now. What’s going on now with those in charge in this country was forecast then and since: They told us what they were planning and now it’s in progress. We can’t say we’re in a totalitarian state now, not yet, because we wouldn’t be talking—I wouldn’t be talking as much as I am—I’d be in jail.

And that’s what your novels are reminding us all of now–that it can happen here. It’s what literature can do, storytelling, and fiction in particular–make us see and feel it.

MA: It’s been done it before. It’s what the novel did in the 19th and the 20th centuries. And it often cast a wide net, looking at the larger society. People read for that very thing. An entertainment and a whole lot more.

But the novel’s been declared dead a few times since then. As a form.

MA: Well, it comes back to life a lot then.

Roaring back in your case, and amen for that and for something you said to me once about anger: You told me you don’t get mad, you get curious.

MA: John Kennedy said, “Don’t get mad, get even.” And I say, “Don’t get mad, get curious.” Why are people doing these things? What’s in it for them? Ursula Le Guin wrote a very good piece on anger in her latest collection of essays. What she says is that anger can be motivating, but if you don’t make structural changes—if you don’t work to change things—it will just fester. Feelings, for the most part, do not justify or excuse action. If feelings justified action, all the men that kill their wives and girlfriends would be justified. They are not justified. Anger is an emotion but it is not, should not be, an action. It doesn’t justify action – it can motivate it. That’s why I support Equality Now, because that’s what they’re doing. They’re working to change laws all around the world to make them more equal for girls and women. They may be angry all day and all night, but if that’s all they were, I wouldn’t be interested. No, they are actually using what fuel they have—their indignation, their knowledge—to change things.

For instance, let’s take climate change. It may make you angry, but if that’s the total of your reaction, nothing is going to change. Is the anger well placed? Is it based on fact? Not a cognitive dissonance? On reality? And if it is based on facts and reality, what are you going to do change the facts and the reality?

What happens when we can’t agree on the facts or the reality, which seems to be the problem at the moment?

MA: What reality isn’t is what you’re feeling in the moment. I feel Amy is a witch, let’s burn her. No, we must ask how can we confirm that Amy is a witch?

I can’t confirm. I won’t confirm.

MA: They may burn you then. Or do other horrible things. If history is our guide.

Yes, historical precedent. You keep reminding people that that’s what you relied on in your creation of Gilead so folks won’t think you’re “weird.” “It’s history, not me.”

MA: But I didn’t make it up.

Yes, yet your choice of these subjects and not just the research but the synthesising of information and the effort of the imagination that went into making the world of Gilead or MaddAddam real and resonant does speak to a pretty singular mind, never mind the constitution required to travel into these dark places – often bloody and made all the more so by Hulu’s rendering. The violence on there is no joke—

MA: That’s the art of the novelist. You want me to say I’m weird? Weird is often used to dismiss people. So let’s not go down that path. I’m not banking on weird, I’m banking on true.

Old is often used to dismiss people, too, especially women. When we had lunch four-five years ago in Boston, at the library, years before the election and The Handmaid’s Tale’s latest rising, you said to me, “My Twitter following makes it hard for them to dismiss me as an old bitty.” Your following was around six figures then. It’s 2.1 now. We had no idea what was coming--

MA: In more than one way. And I am old.

AGL: You have more vigour than people half your age. And for my part your brand of dispassionate passion – “Don’t get mad, get curious” – is all the more important now when it feels that many of are thinking, acting from that fight or flight place in our brains. It’s us versus them, in or out. Men bad. Women good. And Aunt Lydia who drives much of the narrative of The Testaments–she’s a wonderful test of that kind of unnuanced thinking. You chart describe how she was coerced as Gilead took shape, how she positioned herself so that she’d survive.

Totalitarian regimes rely on collusion. Why did people like Aunt Lydia collude? One: they’re true believers, two: they’re opportunists – what’s in it for them? – three: they’re scared. It can be one of these things or a combination of two or all three. If they don’t cooperate and collude they will be killed or their families will be or all of the above. That’s how those regimes put pressure on people. If you read about Stalin’s Russia or Hitler’s Germany or the other kinds of regimes like that, some of which are in power right now, using these methods right now, you’ll find all this.

Like Aunt Lydia says in The Testaments: “How tedious is tyranny in the throes of enactment. It’s always the same plot.”

MA: And for those caught up in the command structure, they are inter-purging each other as quick as they can.

Like Lydia--

MA: Right. They want to climb up the ladder. Keep the power. In regimes like that you don’t get fired. You do or die. Frequently both.

We’re seeing a lot of purging from Trump’s administration--

MA: Different. For the moment you and I are not in danger of getting arrested by the NKVD [Stalin’s security force]. You think Gilead is bad or that the TV series is too violent? Look up the NKVD. It’s important to have that perspective. People are saying Trump is re-creating Gilead. That’s not true. If it were, we’d not be having this conversation. He’s not even a particularly Gileadean figure, more like a Nebuchadnezzar of the right. That guy went mad.

But it’s hard to miss the divisiveness being promoted in America and elsewhere, how the anger we’re all feeling, is informing and deforming the national conversation. We’re all dismayed and many people are afraid—

MA: So suck it up! Why are you so afraid? No one is going to kill you right now. Anybody banging down your door? What you should be doing is figuring out who to vote for in the next election. Which candidate is going to take you the farthest he or she can from Gilead? Panic isn’t helpful.

Yes, but let’s take Twitter, where you’ve amassed such a following--

MA: Twitter is not the real world.

No, but we do need to pay attention about how we talk about things, don’t we? Not run to extremes, and the novels, both THT and The Testaments describe what happens when the society requires black and white thinking, nothing in between, no greys or pick your colour from those crayons of yours—

MA: Crayola grey.

Deep Space Sparkle’s a good one… But those extremes are the place witch-hunts come from. You’ve said you don’t believe in monsters, you believe in people behaving badly.

MA: Well, there are certainly extremes in human behaviour – serial murderers, socio- and psychopaths. But you can never define yourself as a pure angel and others as demons. There are no pure angels. There’s some who behave better than others under certain circumstances – depending on what those circumstances are. For instance, there were people in the French Resistance who committed acts of sabotage against the Germans for which entire villages would be shot as retribution. So what would you have done? We all like to think we would have been heroic, but that’s probably not true.

And that particular truth transcends gender—as we see with Aunt Lydia and others?

MA: It absolutely transcends gender. In fact some of the most effective operatives on either side were female. Guess who was an operative in the French Resistance?

Who?

MA: Josephine Baker.

Man, she had a lot of moxy.

MA: What would you risk? What decisions might you make that could result in your death or the deaths of others?

Would you say you do not believe in evil then?

MA: Well, the more evil acts you do the more evil you are, but people are quite malleable. People who under normal circumstances wouldn’t do terrible things might do them under more extreme circumstances. You may run into a building to save another person, but you would not be called on to do that unless the building was burning. The other question is why do ordinary people do heroic acts? Another woman I knew who was in the French Resistance, a French woman, said to me, “Pray you’ll never have the opportunity to be a hero.” Because those opportunities are usually horrible.

But you are an activist and believe in action, even if there’s no predicting what one will do when put in do-or-die situations. You are no fan of complacency –

MA: No kidding. That’s why you can’t sit on your hands during the next election. None of the candidates are pure enough for you? Take the least worst. You are not too pure. People are too much in the habit of defining themselves as pure and in the know and everyone else as tainted, blind. That’s hubris of an extraordinary kind.

There are so many great lines in the new book but one short exchange at the end reminded me of conversations you’ve had with me when I was foolish enough to express doubt or discouragement in your company. Your two young narrators are on the run, in a small boat:

Agnes: “We’re so far out. We’ll get swept away.”

Nicole: “No we won’t…Not if you try. Now, go! And, go! That’s it! Go! Go! Go!”

MA: Yes, quite right. You can do it, America! Go! Keep rowing. I used a quote from Ursula Le Guin as an epigram for The Testaments. It’s important to read it closely now. “Freedom is a heavy load, a great and strange burden to undertake… It is not a gift given, but a choice made, and the choice may be a hard one.”

We’ve taken a lot for granted, that’s clear. We thought our institutions would do the work for us, to keep us in check. And I should mention you’re not just some Canadian celebrity with great hair telling Americans what to do – you have many ancestors who were American Puritans. Some witches too?

MA: Yes, they were all Puritans and there were a few accused witches among them. But don’t get excited, Amy: There weren’t any real witches or not the sort people meant in the 17th Century. They were not actually having intercourse with the devil. Sorry, kids.

Right, though you have to imagine he’d be pretty good in bed.

MA: Stop that right now. Shame on you. It didn’t happen. Fake news. But yes, my ancestors were New England people who ended up in Nova Scotia. I have a lot of people on 23andMe sending me pictures of their noses, saying, “Look, we’re related.”

You should add that to your list of scary things: All those noses coming for you. I must say I felt just how present the Puritans were in all of us when I worked at Playboy. There’s some serious discomfort about sex in America. Hefner did more than just objectify women, though he sure did that. The magazine was part of the campaign for civil rights and published some of the best writers and thinkers around, including you, at least when I was there.

MA: It’s a catch-22: First, it was awful that Playboy wasn’t publishing women writers, but then when they did there was another contingent who said we should not. Which choice do you want? And if you think the Puritans didn’t like sex, you ought to go back to the Catholic hermits and ascetics. They really didn’t like sex. They thought any woman in any form was one big dollop of pollution. Puritans at least thought holy matrimony was a good thing and literacy: They wanted everyone to read the Bible, and they were very keen on the work ethic and very interested in their consciences, getting right with their consciences. If you want to see an exemplary apology, look up “The Apology of the Salem Jury” from 1697. It’s a template of how to apologise for something you’ve done. We all need to learn to apologise more and better. But many of the Puritans did not apologise. It wasn’t in their interest, and they confiscated property much like the Nazis and Communists confiscated property in WWII. Follow the dollar – who benefitted? Who got the property? During the Salem Witch Trials one man, Giles Corey, wouldn’t confess guilt. Without it they couldn’t take his farm. So they “pressed” him. He urged his accusers to pile more rocks on him – they were trying to coerce a confession from him. He wouldn’t confess. “More weight,” he said. “More weight.”

But women didn’t participate in governance, did they? Couldn’t own land? I hope that poor man had a son—

MA: In most patriarchal systems, men don’t want women to read the Bible because then the men in charge can declare what’s in it and no one can check up on them. They’re in charge of the word of God. That’s the model of Gilead because they don’t want women claiming any authority. The other model is slaves in America. They didn’t want them reading the Bible either. They might get the idea that they were people.

I came to your Town Hall event with Samantha Bee and for every six or seven women there was one man. I canvassed a few – these had watched the TV show but not read THT yet, but there were several very fervent fans. I spoke with one – a lovely guy, passionate. He was proud to call himself a feminist. He had lines from Oryx and Crake tattooed on his wrists: “I am toast” on one, “I am not toast” on the other.

MA: Well, that series has men in the story. No secrets there. He spoke to him. Once the books are out and in hands of the readers I can’t control what will happen—

If tattoos will happen, yes. But, my, was it moving to see the entire theatre get on their feet when you came in. It means people care, people read, are interested in nuance. Men and women are inspired—

MA: They do read, and they do care: They don’t want to end up in some version of a totalitarian state. We’re not there yet but it’s in progress. Of course I’m very pleased they’re reading, but they better go vote.

Keep rowing. Go! Go! Go!

MA: Precisely.

Does it feel a lot of weight on your shoulders? People confusing you with an oracle or a prophet? Elizabeth Moss declaring you’re the mother of us all? More weight…

MA: You get to be my age and there’s no weight. You get very clear about what you can and can’t do.

I sometimes feel you’re this big meal laid out on the table and so many people are bellying up to get their bite. Even me. Right now that’s got to be all the harder – you soldiering on on as you do. It’s extraordinary.

MA: But that’s not me, on the table, that’s their version of me. I can’t control that. Just like I can’t control what they take from the books. I hope for the best but I’ll take the least worst when I have to.

Amy Grace Loyd is Esquire's literary editor (at large) and the author of the novel THE AFFAIRS OF OTHERS.