This article originally appeared in the June 1996 issue of Esquire US. You can find every Esquire US story ever published at Esquire Classic.

Martin Scorsese: My Favourite Coppola Movie

There are certain films in the history of cinema that seem to capture the collective imagination worldwide. They become milestones, reference points for all other works before and after. Their virtues rely on masterful storytelling as well as on the epic scale of their subject matter. The Godfather saga, in its three parts, is one of these creations—a monumental work that has haunted me for years. Constructed like a symphony and directed by a master as a great conductor directs his orchestra, it reaches its highest points of lyricism, for me, in The Godfather, Part II—my favourite of Francis Ford Coppola’s pictures.

I admire the ambition of the project, its Shakespearean breadth, its tragic melancholy in its portrayal of the dissolution of the American dream. I admire its use of parallel editing to accentuate the paradoxes of the historical analysis, Gordon Willis’s dark-hued photography, the actors’ performances, the accuracy of its period reconstruction. It is particularly the film within the film, the story of young Vito Corleone and his journey from Sicily to the Lower East Side, that touched me in a deep, personal way.

Perhaps I saw a bit of my grandparents in that journey; perhaps I recognised my old neighbourhood; perhaps I shared the sadness of the dream turning into a nightmare, of the spectacle of the ancient patriarchal family unit trying to survive its own destruction from within. Perhaps all this and more—the rituals, the feasts, the music, the minor characters—touched an intimate chord within me.

Its use of language is extraordinary. Sicilian dialect becomes more than a secret code for initiates; it is an umbilical cord connected to an archaic society that carries its ancient rules into the New World. By defining us and them, we guarantee our survival.

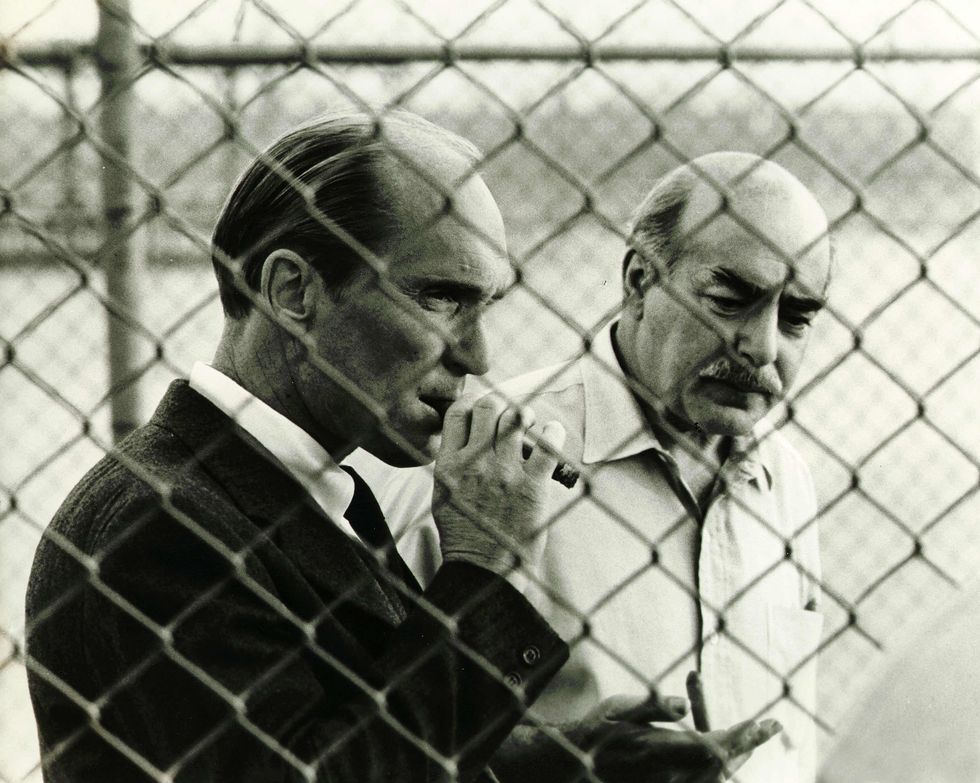

This is why I find Frank Pentangeli—the character played by Michael V. Gazzo—so special in The Godfather, Part II. The way he carries himself, his tone, his language, reveal someone ancient, someone who knows the Old World and sadly witnesses how it has changed. No one knows how to play the tarantella anymore, he complains. His brother’s mere presence at the congressional hearings is enough to have him recant as a government witness. It is the Old World, with its old, unmovable values, that has suddenly reappeared to remind him of an atavistic code of honour.

In The Godfather, Part II, we also witness a different world from the old, crowded neighbourhood. Michael Corleone rules his empire from his fortress-like Lake Tahoe estate. He deals with Batista’s Cuba and Las Vegas. He's traveled a long way. His accumulation of wealth arid power has cost him all human ties: wife, children, brother, associates. In fact, he has lost his family, his main reason for accumulating wealth and power to begin with. Unlike the gangsters of the Hollywood movies of the thirties, he doesn't die but lives on-which seems to be an even greater punishment.

Francis Ford Coppola: My Favourite Scorsese Film

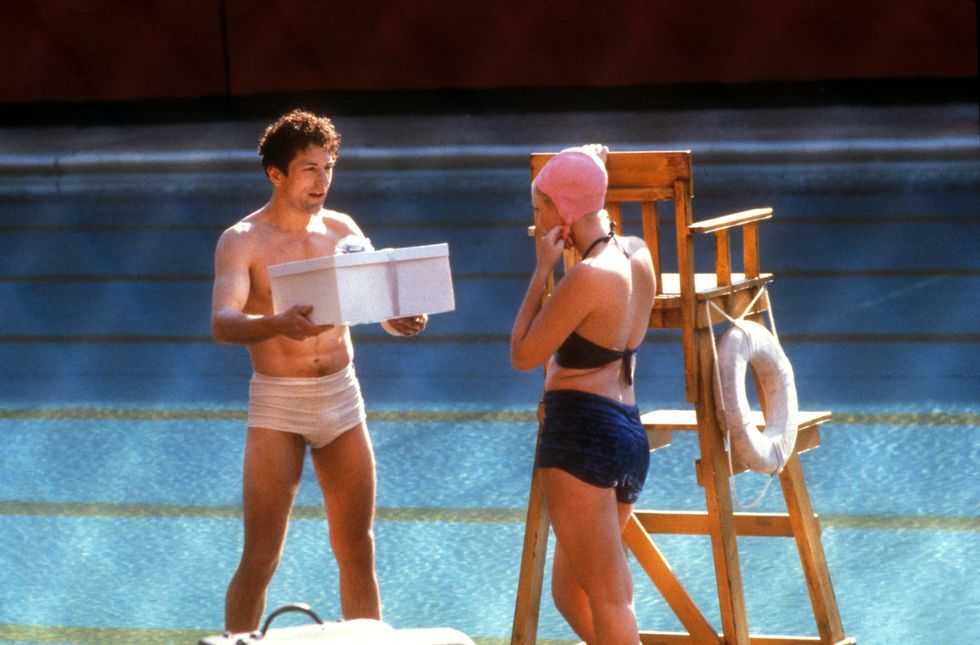

I have several favourite Martin Scorsese films, actually—I love Mean Streets, The King of Comedy, Who’s That Knocking at My Door?—but Raging Bull stands as his towering achievement. I think it’s in this film that he orchestrates all the elements—the conception, the acting, the images, the style—into something that tells a particular story (of Jake LaMotta) and then goes beyond that. Ultimately, the purpose of art is to illuminate our times and the things that are important to us, and Raging Bull does it, seemingly effortlessly, as few films ever attempt, much less do. La Dolce Vita and 8 1/2 have those kinds of proportions, and so does Raging Bull. Every performance in it is great because of Marty’s use of improvisation within a dramatic structure, whereby on the one hand he lets the actors feel the freedom of life, so they can say what they want, but on the other he controls them so that everything they say and do contributes to the overall film. It has spectacular visuals, wonderful use of music and rhythm, beautiful editing, and then those huge, universal human themes.

All of us who make films in this country are trying to figure out how to swim with the tides that make it possible to be a viable director while still addressing personal feelings in our work. Being a director is kind of like being Christo, the artist: Part of his art is in the wrapped building, but another part is in all he had to go through to bring it off. Even after Raging Bull, nobody was telling Marty, “Hey, here’s the money to make whatever movies you’re passionate about.” If he had been born to a family that had $500 million lying around, he might make a film at that level every year.