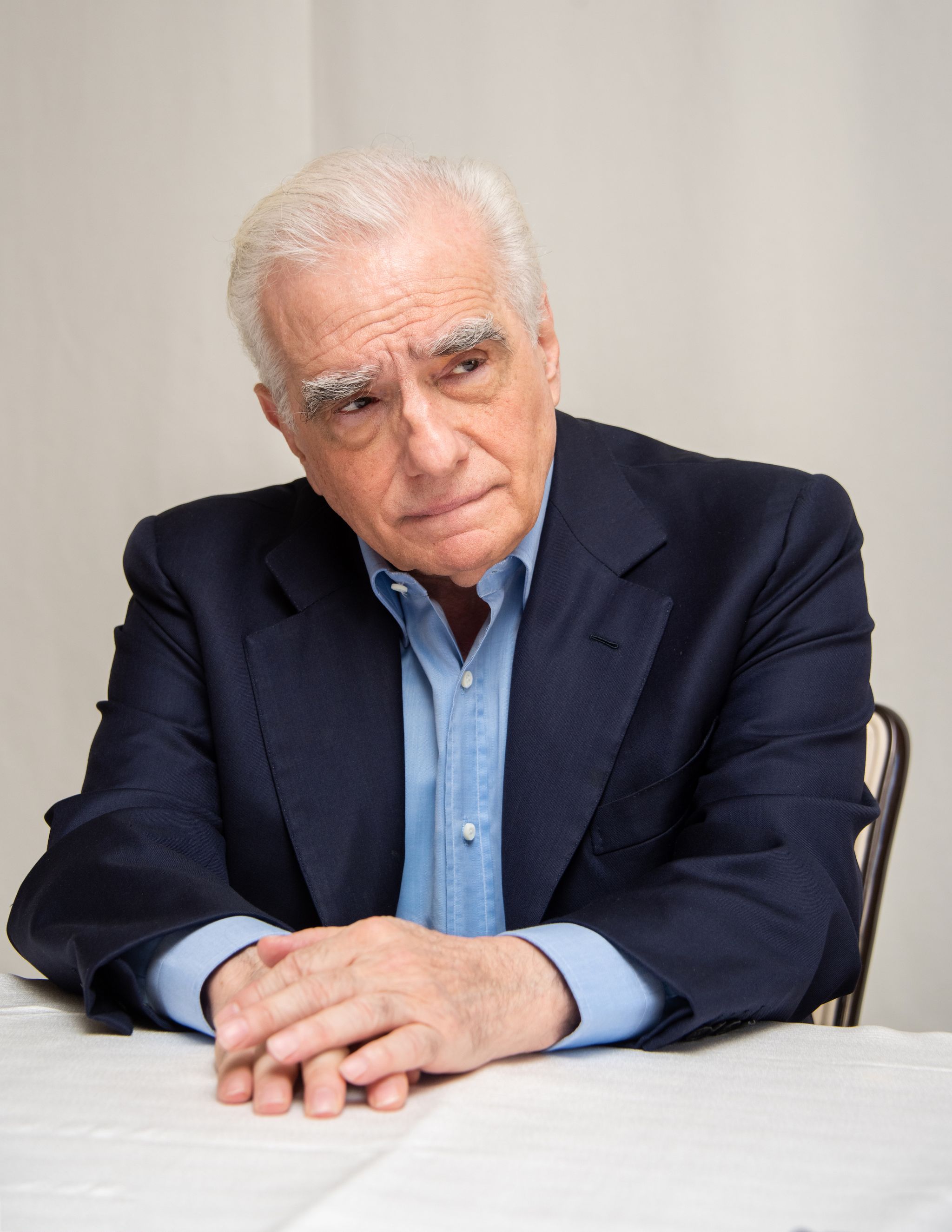

"That's my lunch," says Martin Scorsese, holding a tiny, crustless tea sandwich between thumb and forefinger. We're sat at a round table in a hotel room just off a sodden Trafalgar Square in mid-October, 10 journalists and one extremely famous director, who's considering a sandwich. He chomps through it with a little "mm-hmm" on each bite, and finishes his last with a flourish.

"OK, what have we got, everyone?"

Questions, mostly, about his latest gangster saga, The Irishman, a film which is remarkable in several ways. For one, it's arguably the year's marquee film, but will likely be seen by most people at home on Netflix. Then there's all the de-ageing tech stuff, the miraculous VFX which allows Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and the formerly very retired Joe Pesci to summon up their own ghosts.

But most of all, it's a final heaving together of New Hollywood's greatest living totems, to make the kind of film they used to make – and which made them – and which they understand better than anyone else. After all, Scorsese, De Niro, Pacino and Pesci are all over 75 now, and part of what makes The Irishman exciting is that so few people believed that anything like it could happen again. Even Scorsese and De Niro. "Ultimately, we decided, I think about nine years ago – we were in our late Sixties then and we realised we better–". Scorsese pauses and rephrases. "We know we have to do one more picture."

They had intended to make a film based on Don Wilmslow's thriller The Winter of Frankie Machine, but Scorsese lost his appetite for it. "I could not put the two together," he says. "First of all, because a genre piece is very difficult for me to do. So I no longer had, maybe, the enthusiasm for that sort of thing anymore. And there's no more time – you're too old, no more time."

Then screenwriter Eric Roth gave De Niro a book while they were working on The Good Shepherd, the actor's debut as a director. Charles Brandt's I Heard You Paint Houses told the story of mafia hitman Frank Sheeran, and De Niro was electrified. So much so that he tried to talk Scorsese through it in the director's editing room. "He sat down, he started talking about the book, but he became – I could see he was really emotionally involved with the character," Scorsese says. "So much that he couldn't describe – he couldn't really speak."

Scorsese was sufficiently convinced by De Niro's passion that they junked Frankie Machine even though it had already been greenlit, and started putting together The Irishman. De Niro suggested Pesci and Pacino, the latter Scorsese says he had been trying to work with "for years". The problem, though, was that the narrative jumped across more than six decades.

"I just thought, I can't. It's – no. No." It wasn't just about whether the prosthetics would look strange or if they could find the right kids to play the three men. It was about New York City.

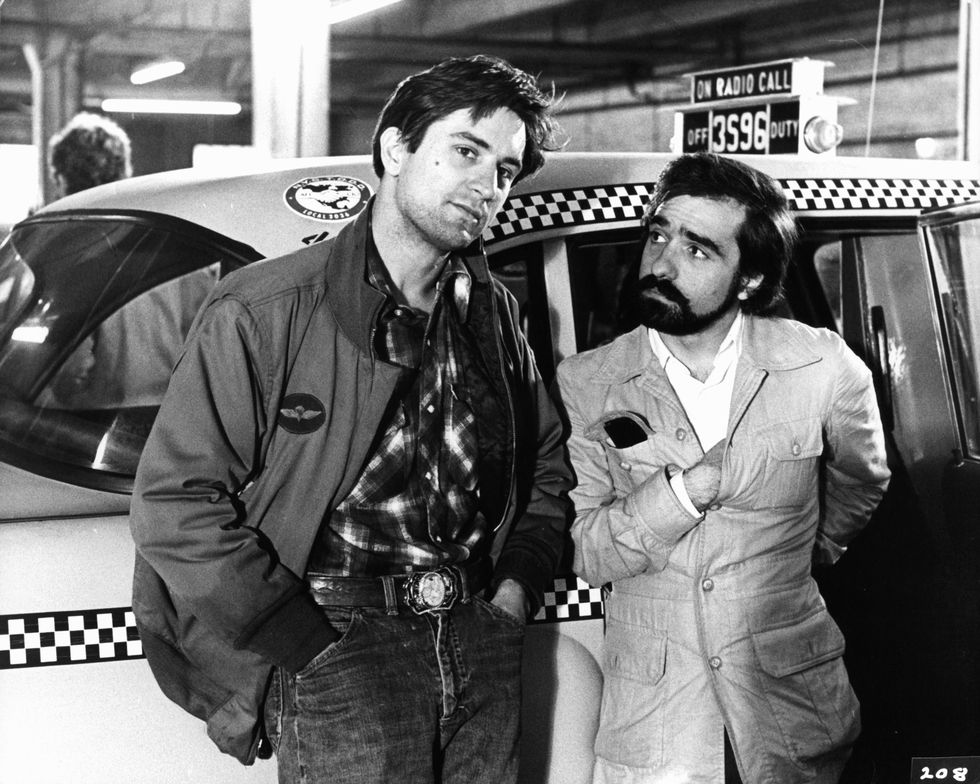

"De Niro is the only one who knows where I come from," Scorsese says. "He was 16 years old. So was I. He was on Kenmare Street. I was on Elizabeth. He knows the people I grew up around. He knows the way of life. He knows a gesture. He knows the look in the eye. He knows it. Pesci, the Bronx. I have no idea what happened there. That's up to him. New Jersey? No idea."

That deep connection of experiences makes finding young actors to play young versions of De Niro, Pesci and Pacino pointless, he says.

"Even if they come from a similar area, the context of time is different. You'd have to explain who, you know, who [jazz singer] Billy Eckstine is or, you know, [singer and actor] Jo Stafford, as opposed to Patti Page as opposed to Ella Fitzgerald. And then you go into rock'n'roll. So he just knows the context."

That New York City he and De Niro grew up in, and which looms over Mean Streets and Taxi Driver in particular, formed the pair. But it isn't somewhere Scorsese would be keen to visit again At least, not unless he's behind a camera.

"As a taxi driver on Eighth Avenue, that time was terrible. Everybody talks about the wonderful 42nd Street – it was horrible! It's bad now with the Disney stuff, but it was really bad then. And believe me, unless you were looking for certain things, like, I'm telling you: it was scary."

It's often quite hard to tell if a question leaves Scorsese wounded, or perturbed, or bemused, or if he's just thinking really hard. When he's telling a story he knows well, his eyebrows are raised with a beatific calm. When he's thinking on his feet, the brow furrows. He speaks quickly, in measured but concentrated bursts. He speeds up when he's talking about films: The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, or watching Citizen Kane on TV as a child – "I couldn't tell whether the commercials were part of the movie, because the style was so wild" – or Fred Zinneman's 1966 biopic of Sir Thomas More, A Man For All Seasons.

He's less giddy about Marvel films, as you've definitely heard by now. This interview happened before Francis Ford Coppola, Ken Loach and other grand old men of film joined Scorsese in decrying its films as "not cinema", and a long time before Scorsese's New York Times op-ed explaining exactly why he objects to these vast franchises squatting on multiplex screens for months on end. But he'd clearly come to those conclusions long ago.

"The audience that likes those films: good, it's good for them," he says. "And the films are beautiful, extraordinary in the making, the way those films are put together. I just feel they're not really films. I feel that they're something else. I feel that they're a new form, in a way. The theatres have become amusement parks and the films are theme park rides. But there is a real cinema, true cinema, the cinema we know from the past 115 years or so. Why not use those elements? And why not coexist that way, and not let the technology take over? The technology is not going to do the work for you."

The Irishman is cinema as it was once made, and if it acts as something of a reunion, it's also a final judgement on the violent men Scorsese and De Niro have put on film before, and an elegy for the kind of film those men appeared in. The hitman Sheeran's bleak epilogue is the most affecting segment of the film, and shows a Scorsese protagonist having to live with what he's done in a way that Travis Bickle, for instance, never did. A lot of people die at Sheeran's hands in The Irishman, and faced with his own mortality he's haunted by choices he made. "God forgives him," Scorsese says. "He can't forgive himself."

"The bottom line is we all die alone," he adds, breezily. "So we gotta face it. You know, maybe fast, maybe slow – we go alone." Scorsese isn't getting angsty, these are just facts. "That's something to contemplate. That's something to say 'OK, if I am alone, what value would there be in the last days and those last hours from existence?'"

A while ago, Scorsese read Vladimir Nabakov's autobiography Speak, Memory. It's a cheery read, which begins: "The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness."

"He describes the light coming through a window when he was a baby as a major point in his life, rather than meeting a certain person and going to the facts, it's those elements that would possibly are the things you think about it the last moments," Scorsese says. "And it just has to be, so why not embrace it?"

As funny and gripping and warm as The Irishman is (at points), there's something spectral about this final meeting of Hollywood's biggest beasts, which gives it a circumspect, reflective feel. Scorsese has said that the themes which have haunted him through his career return in The Irishman, but what are they? And what does The Irishman say about them that Mean Streets, or Taxi Driver, or The King of Comedy didn't? The eyebrows knit.

"You know, it goes back to Mean Streets. I keep thinking of how you, how you, how do you – ." He stops and starts a few times. There's a long pause. "How one could – of course, this word can be defined different ways – but lead a good life? Outside – how should I put it?" He tussles a bit more, concluding that he means people who don't have to observe limits that "other people have to deal with – institutions, all of this sort of thing".

"And how can one be fair? What makes a good man, and also makes a good woman? What makes a good person, you know, and ultimately is that person consumed by everything? At first I thought, when I was younger, it's a matter of a vocation, a religious vocation. But I thought when I was really young, that the vocation would take me out of the world, whereas I realised the vocation should be in the world. And that's hard. That's all. And so these are the thoughts. They play out in homes around the world, and kitchens, and in bedrooms everywhere, and boardrooms. But it's really more brutal and more direct in a world like Irishman, or now I think pretty much anywhere." The world, he says, is now "more obviously brutal".

"And we're all facing it. What's the right thing to do?"

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox