When, in January this year, Spotify announced that it was spending $340m (£307m) to buy two small podcast companies, it confirmed what a lot of people in tech had suspected for a while: podcasting had hit the big time.

Back in September 2018, the multi-billion-dollar entertainment conglomerate iHeartMedia had bought podcast publisher Stuff Media for $55m (£49m), and at the end of 2017, Google had quietly acquired the Spotify-for-podcasts-style app 60dB for an undisclosed amount. The latest Spotify deal now sent tech bloggers into a frenzy of next big thing-ing, and in June this year, as if to justify the hype, Spotify revealed it would also be making podcasts with Barack and Michelle Obama’s company Higher Ground Productions.

It isn’t hard to understand the excitement. There are now more than 700,000 active podcasts around the world, with large-and-growing audiences (about 62m listen weekly in the US; over six million in the UK). And because audiences are young, trendy and affluent, ad revenues are growing at insane rates. Podcast revenue is expected to top $1bn in 2021. As Ira Glass, the host and producer of This American Life and one of the people behind Serial, says, “There’s a gold rush going on right now. It’s a Wild West. And it’s going to be funny to see how it plays out.”

This cash-rich, fill-your-bytes boom is a far cry from the early days of podcasting — or“audioblogging” as it was first known — when tech geeks got excited about sending 100MB audio files over creaking dial-up internet connections. The exact origins of the medium are often testily disputed by veterans; the real problem being a lack of clarity about what a podcast is. Is it just any downloadable digital audio file? Can a repackaged radio show really be a podcast? The purists, and the people who began audioblogging with a real vision, say no, never. Podcasting grew out of blogging, and it was a way for bloggers to share news with each other, using technology that enabled them to receive updates automatically. Radio played its part, they say, but true podcasting was about anyone being able to put themselves and their content out there: its history is about those connections, not about early MP3 players and the like.

If there’s one man who could be called “The Podfather”, it’s probably Dave Winer, a US software developer, entrepreneur and writer, who the BBC named “the father of blogging”. In what would be the first of many cases of geekdom and glamour colliding in podcastland, in the early Noughties, Winer ended up collaborating with a Dutch MTV host called Adam Curry on technology that allowed people to automatically download audio files, and be alerted only when the files were there ready to play. Winer used the technology to create early podcasts with the US journalist Chris Lydon, and then in 2004 he began adding audio of him speaking to his own blog. This prompted Curry to create his own, much slicker show, Daily Source Code, that August. And suddenly it began to happen.

In that same year, guests at a BloggerCon held at Harvard University heard enthusiastic presentations about audioblogging and a demonstration of a script for downloading MP3s and adding them to iTunes for transfer to an iPod. Shortly afterwards, Curry created his own script for moving MP3s to iTunes, allowing users to plug an iPod into a computer to charge at night, and wake up to find their selected podcasts downloaded. WGBH Radio in Boston, a National Public Radio station (NPR is essentially America’s less-well-funded BBC), became the first station to make its programmes into podcasts. And entrepreneurs Eric Rice and Randy Dryburgh launched Audioblog (later Hipcast), the first commercial podcast hosting service.

Carl Malamud, founder of Internet Talk Radio, the first computer-radio talk show: “In the early Nineties, I was working for a non-profit organisation I founded called Public.Resource.Org. I was in ‘the new’ business, and very excited about the internet. I started a non-profit internet talk radio station in 1993, making downloadable radio shows. I had this idea for a show where I’d interview researchers, engineers and a variety of other troublemakers, called Geek of the Week. It became our flagship show.”

Dave Winer: “I started the first blog (Scripting News) in 1994, this year is its 25th anniversary. I was also CEO of Userland, which produced the first blogging softwares during the Nineties… My idea was always [to create] writing tools that would enable ordinary people to publish.”

Malamud: “Internet Talk Radio had to close because of funding in 1996, but there was a lot of interest in us. By ’96, I’d got Congressional press credentials, helped put the White House online for the first time, did the first live congressional hearings on the net. It was a blast.”

Winer: “I think there are a lot of misunderstandings about what the process that led to podcasting was… My first experience was in a meeting with Adam Curry in New York at the end of 2000.”

Adam Curry: “I was a frustrated radio guy. I just wanted to do radio without some douchebag telling me what to play and say. I’d moved to America to start a tech company, sold it for a lot of money, and moved back to Europe, and this idea had come to me. At the time, the internet was slow so if you wanted to listen to a piece of audio, it was click, wait for some significant time, click, click again, and finally it would play. I thought, ‘What if your computer knew to download content you were interested in but would only tell you that it was available when it was downloaded, so you could click and play immediately?’ I put that idea together with Dave’s blogging software, which allowed you to transmit ie, do a blog post and add it to your feed, and receive feeds, and I called him because I wanted to meet and tell him I thought this was a good idea.”

Winer: “Adam was in this kind of fancy, rock star hotel. Adam was something of a rock star himself, given his MTV background.”

Curry: “I think Dave thought, ‘Who’s this MTV guy, what the fuck does he want? Big hair, leather jackets? Fuck off!’ I tried to explain my idea, and I tried to use his blogging software to show what I meant.”

Winer: “He showed me some code of mine that he had hacked up and it was absolutely egregious. It could never work, but it communicated the idea he had been trying to explain with hand waving, that there was a problem with media and the internet… I got the idea, said this is really interesting. At the time I had been working on a computer standard that allowed computers to automatically check for and download new content from each other, and I thought it would be just a simple modification. But I also had to make software that would produce these feeds, that had enclosures, that could contain big media objects like MP3s or movies. Then I had to create software that would aggregate it, gather up all the different sources and then put them in a place where a human being could listen to them. I created a channel with Grateful Dead music on it. It was a nice experiment, but nobody cared or understood. It took me, an amateur at radio, to create a podcast of me [talking] to give people the idea that they could do it. That’s what got Adam off his butt and got him doing Daily Source Code.”

Curry: “I was forbidden from using Dave’s software, but I hacked together an Apple script to tell your computer to look at a feed, you know, and when it saw an audio [file], it would download it and synchronise it to your iPod. It basically created what we now know as a ‘podcatcher’. Then I decided to do a radio show, Daily Source Code, talking about the Apple script. I just put that out there, but people were subscribing and listening, and I noticed there were other software developers who had also started building software to download and manage audio.

“We had no name for what we were doing. It was called ‘audioblogging’ sometimes, but there were all kinds of weird descriptions. Some people would describe them as ‘online soliloquies’, which in a way was true, of course.”

Miranda Sawyer, audio critic, The Observer: “The journalist Ben Hammersley first used the word ‘podcasting’ in The Guardian in 2004. When I interviewed him about it, he said he’d made it up. He’d written a story about automatically downloaded audio and he’d been asked to add 20 words at the last minute suggesting a title for this new phenomenon. He made up some words and ‘podcasting’ was one of them.”

Curry: “We heard the word ‘podcasting’ had been used to describe the show we were doing. It turned out a guy named Dannie Gregoire had used this phrase, and we were like, ‘Fuck, this is great. We’ll call it podcasting’. Now [we know] Ben Hammersley had coined this phrase in an article he wrote earlier. For sure, he was the first to use the phrase, but it was really Dannie who applied the name to what podcasting really was — automatic downloading and synchronisation of content. It was a very controversial name, obviously, because people were like, ‘Well, it ties it to Apple’. I said, ‘Yes, they’ve got the fucking device’. So you know, there were a lot of holy wars about that. To me, it’s Dannie who came up with the name.”

Sawyer: “Six or seven months later, Ben got an email from The Oxford English Dictionary asking where he found the word. The Guardian piece was the first example they could find. He told them he made it up, and they said, ‘Well, congratulations, it’s word of the year’.”

Dave Winer had always believed people would love podcasting as soon as they grasped what it was, and he was proved right. At first, its popularity grew at an astonishing speed. At the end of September 2004, searching for “podcasts” on Google found around 500 results. One year later, that number had risen to 100,000,000. Some 3,000 podcasts had been published by the end of 2005, and the mainstream media frothed about the curious new “free amateur chatfests” (thanks, USA Today). Worthy institutions piled in: the White House made George W Bush’s presidential address downloadable, and the BBC began putting its shows out in podcast format. With business partner Ron Bloom, Adam Curry set up PodShow (later Mevio), a network to help people publish, market and discover podcasts.

The great leap forward came in 2005, when Apple added support for podcasts to iTunes, which meant listeners no longer needed a separate application to transfer them to an iPod. Radio stations around the world made their programmes available on iTunes, with LBC becoming the first to offer podcast-only shows in 2006. At the end of 2005, The Guardian offered a version of Ricky Gervais’ Xfm show as the first paid-for podcast series: it became a phenomenon and by September 2006 the series had been downloaded almost 18m times. Gervais’ record would be broken by Adam Carolla’s talk show in 2011.

Curry: “Almost immediately, I realised how powerful this was. The typical radio things — ‘Hey, it’s 9:35am, 25°C outside’ — all that fucking shit was gone because, you know, podcasting isn’t local, it’s global. It meant you couldn’t do all of the old typical DJ-isms.”

Dawn Miceli, co-host The Dawn and Drew Show, an early podcast on Adam Curry’s PodShow: “When I was a child, I had this audio project I called ‘WKID’, Wisconsin Kid Radio. I’d record these little tapes and I would be like, ‘Hello, this is Dawn Miceli for WKID’. I’d interview my friends and siblings and just talk about the weather and what’s going on in the world. I’d tell stories and sing songs, it was so fun. In summer 2004, my partner was going on about this nerdy thing he was doing with a friend, making all these little radio shows on MP3. It wasn’t called podcasting then, it didn’t actually have a name. Drew wanted us to do this nerdy radio show, and I was like, ‘OK, I know how to do this’. So we started making The Dawn and Drew Show just on a whim, just talking about our day. But we’re just this dorky, ratty-tatty punk rock couple living on a retired dairy farm in the middle of the country in Wisconsin, we didn’t think anyone would listen.”

Zoë Jeyes, London Podcast Festival producer/programmer: “From the beginning, there was a special thing about those podcasts that are just a group of friends having a really funny conversation. There isn’t really another medium like it. It’s not improv, it’s not stand-up, it’s people who are very funny sat in a room chatting, in a way that makes you feel like you’re in that room and you’re part of that conversation, laughing along. Only a podcast can do that, I think.”

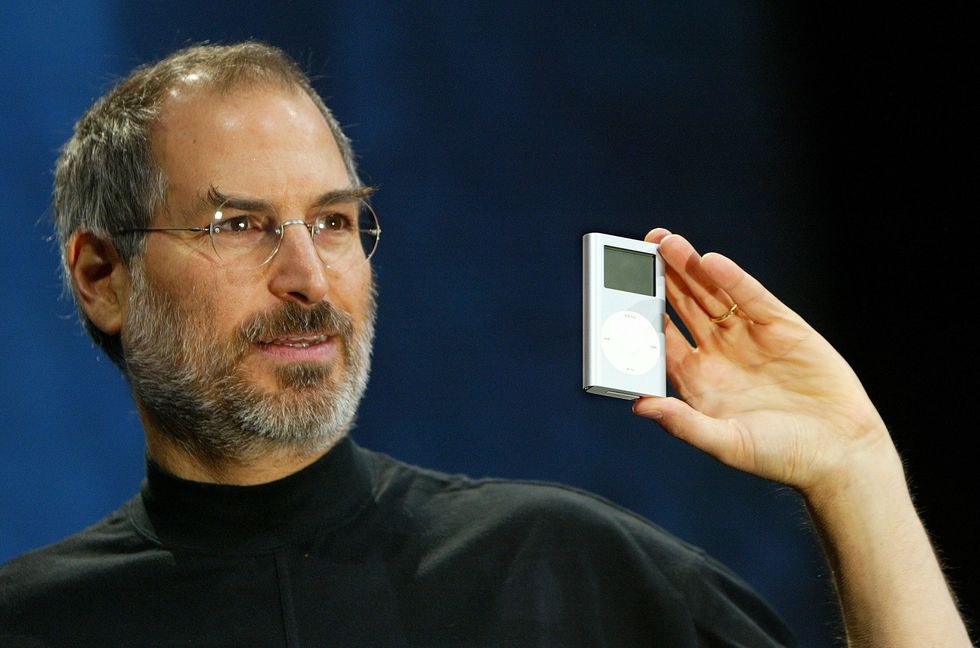

Curry: “In 2005, I got a call from Steve Jobs asking if I could meet with him. The meeting lasted for an hour. We were just chatting about all kinds of stuff, and he says, ‘Listen, I want to put podcasting into iTunes and take it into the iPod. Is that OK?’ He understood it exactly. He wanted the community. I said, ‘Yes, and in fact, I’ll give you my whole directory to start it off’. There’s actually a famous video of Jobs introducing that onstage. He was quite the showman.”

Ira Glass, This American Life host: “Before podcasting was happening there was a company here in the States called Audible that now is worldwide. Back in the Nineties, they were trying to get people to download audio content onto MP3 players, and the tech was so new that when you signed up they would send you the MP3 player. They reached out to us [at This American Life] and for a couple of years they offered episodes of This American Life that people could pay to download. When podcasting started to take off and people started to download stuff for free we turned to them and said, ‘You know, the world has moved on, and so we’re going to just have to do this stuff for free’. I remember they were very upset about it. The head of Audible actually, sort of, shook his fist and said, ‘You’ll be back! This so-called podcast thing is doomed!’”

Miceli: “All of a sudden, all of these people started tuning in from around the world, and they were loving it, just because it was reminding them of conversations that they had with their friends, or it was just real people talking about real stuff without a producer saying, ‘Let’s jazz it up for the numbers!’ It was just a raw, natural thing. I don’t know how many times I’ve had to fart on the podcast. Obviously, you can’t script that kind of stuff.”

Matt Hall, head of On Demand Audio, Wireless Group: “In the UK, the whole medium was basically created by The Guardian’s first Ricky Gervais podcasts.”

Jeyes: “The first podcast I was aware of, and the first one that I listened to, would have been the Ricky Gervais podcast. I remember it coming out around the time that The Guardian came up with the term ‘podcast’. It was my first favourite, as it was for many people.”

Mike Fallek, Hackthought producer and I Podcast Too director: “Ricky Gervais made one of the most controversial decisions in all of podcasting history, one that made entertainment history. He went backwards. Everyone told him, ‘Don’t go back to radio’, because if you’re a radio star and you have a hit TV show, you don’t go back to radio. That was a decision that created a format. Before him, no one in America was making podcasts in any other way than just, go in your garage and do it.”

Bill Brewster, DJ, host and producer, DJ History: “Personally, I wasn’t influenced so much by American podcasts as by John Peel’s old BBC radio shows. I think podcasts are today’s fanzines, really. I think what podcasting has done though, is open up esoteric subjects that the BBC doesn’t understand. The big fault with the BBC, and in particular with Radio 4, is that it’s extremely middle class, so they don’t really understand any kind of street, popular or working-class culture. So a lot of podcasts filled those gaps. They’re really great for things that you don’t feel are being catered for by the BBC.”

Hall: “In the early days, there was a difference of tone between British and American podcasting. National Public Radio got into it at an early stage and set that NPR tone of voice — the tone of shows like Serial or Invisibilia. I think it also influenced the length of US podcasts — they’re often longer because, I suspect, a lot of NPR radio shows are often over 90-minutes long. Early podcasting in the UK was driven a lot by BBC speech radio, which comes in chunks of 30 to 45 minutes, although they didn’t have the traditional BBC tone. Think of something like Answer Me This! It didn’t sound like BBC voices.”

Olly Mann, Answer Me This! and The Modern Mann co-host: “It’s difficult to remember now but in 2006, when Helen [Zaltzman, co-host] and I were planning Answer Me This! the culture aimed at people in their late teens and early twenties was really either patronising or really trendy. We wanted to make the kind of show that we would have liked when we were sixth formers — that kind of Adam and Joe, Lee and Herring, terrible juvenile style with a sensibility for switched-on, curious, ironised teenagers. There wasn’t room in the mainstream media for someone our age — 25 — being geeky and funny. The people who were doing it, Charlie Brooker and people like that, were 20 years older than us. We wanted a show where we could be serious about silly things and be silly about serious things.”

Hrishikesh Hirway, producer and host, Song Exploder: “Marc Maron’s WTF, which launched in 2009, had a big influence on me. I loved how his guests talked to him as a peer, which meant they went straight to a deeper level of their craft and sounded more natural. I wanted to ask my guests on Song Exploder questions that let them go to that more natural, instinctive, deeper place of how they actually work and what it is they actually think about.”

Sawyer: “Podcasting really took off early last decade, and you had stars like Adam Corolla breaking the download records and Alec Baldwin getting involved [Here’s The Thing, 2011]. I have a theory that one reason for them getting more popular was that iTunes was a nightmare and Spotify hadn’t really got going. Everyone was frustrated with the music on their phones so they started listening to podcasts, because they worked fine.”

Just when it seemed podcasts would keep on growing forever, they stalled. In 2013, the number of people saying they had listened to a podcast in the last month fell for the first time in five years, and Google recorded a three per cent drop in podcast searches. For a while, it looked as if they’d reached a plateau and, with only about one-in-14 British people listening to them, were proving less popular than Dave Winer had once hoped. But in 2014, everything changed again.

Julie Snyder, Serial producer: “I had been a producer at This American Life since 1997. In 2013, we’d started talking about doing a new, spin-off weekly show featuring various news stories from the previous seven days. We were going to do it as a podcast because it was cheaper and easier than radio.”

Dorian Lynskey, Remainiacs host: “At that time it was still kind of ‘phase one of podcasting’. I mean, I loved Slate’s podcasts, but generally podcasts just seemed to be ticking along... I don’t remember talking about them much.”

Snyder: “At the last minute, just before we committed to the idea, Sarah Koenig said she had this other idea for a show which came back to the same story every week and told another instalment. She had the idea because she was already working on the Adnan Syed story.”

Hall: “The interesting thing about Serial was the way the presenter put herself in the story. In traditional radio you’re taught to let the people whose story you were telling recount their own story; Sarah Koenig changed what the presenter did, and would admit when she was

unsure about stuff. It was really refreshing and a really different way of doing it.”

Glass: “Julie also consciously structured it like a television show in some ways. Like doing ‘previously on Serial…’ at the beginning of the episodes, and things like that.”

Snyder: “I found the idea intriguing, because it would work well with the podcast format, which didn’t have to be a certain length, and allowed you to control when people could listen to the new episodes. Although we definitely felt like, ‘Who listens to podcasts?’ At the time, Ira Glass had been trying to encourage people to use them by posting on our website a video of him and his 87-year-old friend using podcasts, which was meant to show how easy it was! Our goal was to get 300,000 downloads per episode, as that would raise enough to cover the costs.”

Glass: “We got very lucky in that the month before Serial hit, Apple made the podcast app a part of the iOS [8] on iPhones. Until then you really had to care about podcasts to discover them, but suddenly you have this app and when opened it lists the 10 top podcasts and you just press one of them and then it’s playing for you.”

Snyder: “Serial launched on 3 October 2014 and we hit 300,000 downloads five days later. I think we hit a million by the end of October. We were really shocked. I asked my friend PJ Vogt, who’s the host of the podcast Reply All and the-person-I-know-who-understands-the-internet, what was happening. He said, ‘the internet loves to solve other people’s problems’.”

Damian McKeown, planner at Saatchi & Saatchi: “They reached 68m downloads and won a Peabody Award in the end, which is very prestigious. It was the first time a podcast had won one. It changed the game.”

Glass: “One thing we hadn’t anticipated was how much people like a crime story. People are really into that. We were just doing investigative reporting on what happened to be a crime story. We really didn’t think about it but then afterwards true crime became this massive genre in podcasting.”

Donald Albright, Tenderfoot TV co-founder: “Modern true crime podcasting all goes back to Serial. I look at it as ‘BS (Before Serial)’ and ‘AS (After Serial — meaning one-to-two years after season one aired)’. BS, there were some good episodic shows, and that trend continued for a while, but after Serial season one you see a major shift in long-form serialised podcasts — from Crimetown to Up and Vanished to Dirty John. Everyone, including us, wanted our own Serial.”

Payne Lindsey, Tenderfoot TV co-founder, and host of Up and Vanished and Atlanta Monster: “I made Up and Vanished because I wanted to make a true crime documentary but didn’t have any money to film anything the way I wanted to. I had just come off of bingeing Serial season one, and I had never been so compelled by an audio story. I started making an investigative podcast series looking into the disappearance of Tara Grinstead [an American beauty queen and history teacher from Georgia] in 2005. The police had never been able to explain what happened to her. I uploaded the first episode of Up and Vanished in 2016, and six months later, there were two arrests in the case. I’ll never claim that I solved anything, but I think the renewed interest from the podcast, and all the poking around I did, played a huge part in the break. The day that Ryan Duke was arrested for Tara Grinstead’s murder is still surreal to me.” [At the time of writing, Ryan Duke was awaiting trial for Grinstead's murder; in March 2019, another man, Bo Dukes, was found guilty of helping to cover up the crime and sentenced to 25 years in prison.]

Jeyes: “I think in the UK, My Dad Wrote a Porno was the significant tipping point, more than Serial. Way more people my age recommended My Dad Wrote a Porno to me than Serial. Around 2015–’16, it was a big word-of-mouth sensation. You’d see people on the London Underground giggling and go, ‘Oh yes — they’re listening to it’.”

Mark Ratcliff, managing director, Murmur Research: “Around 2016–’17 you could see a shift happening. You’d see people with headphones in, but they obviously were not listening to music — maybe their fingers weren’t tapping, maybe they were laughing. So there was little outward change, but what they were listening to had completely changed. Unless they listened themselves, clients didn’t realise. It reminded me a little bit — I mean, it’s completely different, but, you know — of the early acid house days where young people were taking ecstasy, but adults didn’t realise because they couldn’t read the signs.”

James Cooper, co-host of My Dad Wrote Porno: “We thought we might get a niche, dedicated audience who shared our sense of humour. We certainly didn’t expect where we’ve ended up! It’s always hard to guess what makes something a success but we think it’s because it’s authentic and it’s relatable; people often say it’s like hearing the conversations they have with their friends. And we’ve all got embarrassing parents.”

Jeyes: “When we launched the London Podcast Festival we had the first-ever live shows of My Dad Wrote a Porno, which I think was a big tipping point for live podcasting in this country. The ticket sales crashed our website and we had to put on repeat shows. The atmosphere was like a party.”

Jamie Morton, co-host of My Dad Wrote a Porno: “We’re going on our second world tour next year. The show is centred around a chapter all about [character] Belinda [Blumenthal]’s 30th birthday party, which should be pretty raucous. We’re starting at the Sydney Opera House.”

Whatever the reasons, podcast listening figures began to climb again after 2014. In 2015, as if to seal their new, post-Serial legitimacy, Barack Obama appeared on Marc Maron’s WTF podcast: the first appearance of a sitting president in an online podcast. The rise of Trump and the Brexit debate seemed to stimulate news and political podcasters, with two of the most respected shows, Pod Save America and The New York Times Daily, launching in 2017. Most of all though, the period after 2014 was marked by experiment and testing the boundaries of the new, booming medium.

Lynskey: “Podcasting benefited from people wanting to understand more. Whether it be Ted Talks or post-Malcolm Gladwell books, there’s a whole industry of… basically, the ‘thinky section’. Listeners became sort of willing to devote more time than I think traditional broadcasters would have given them on a subject.”

Hall: “We’ve seen traditional speech radio taking pointers from the way that podcasters put stories together. You look at programmes like Grace Dent’s series [The Untold] on Radio 4, say. They’ve come from quite an NPR-ish world, telling stories and with the producer sort-of stepping back out of the production to actually consider what’s being said.”

Mann: “For me, what we do on The Modern Mann, which has a magazine format, is genuinely public service broadcasting. We’re taking really difficult subjects — rape, paedophilia, the impact of war — and we are presenting those topics to an audience that thinks they’re downloading an entertainment show because it starts with a light-hearted conversation about trends. And because it finishes with a sex question as well, which is kind of a titillating way to keep people listening. What I’m really proud to do with Modern Mann is really do what the BBC is supposed to do, which is say, ‘We’re going to give you a difficult subject; we’re going make it something that you feel like you want to opt into because it’s fun’.”

Stan Collymore, retired footballer now hosting The Last Word with Stan Collymore: “Football news on television or on radio, is just, ‘How did you play today? What do you think makes a great game?’ You do soundbites. This gives little away about the players. On The Last Word, the interviews have gone down very well, and the honesty’s gone down very well. Podcasting can present an experience. Like you can turn up to somebody’s house… I mean, I interviewed Gary Neville at the top of Hotel Football, which he part-owns, on a kind of five-a-side football pitch. Jamie Carragher was [interviewed] in a back room of a pub, very close to his house. He was in his gym gear.”

Miceli: “[Crowdfunding platform] Patreon, which started in 2013, made a difference. We’d utilise Patreon as a way to say to audiences, ‘Hey, do you guys want extra content? You can be part of this secret fan club world for only two dollars a month!’ That kind of thing is new. It’s cool that happens because people are now able to help financially support things that they like.”

Lynksey: “What surprised me is that it was viable financially. We did Remainiacs for free for about a year until the Patreon support really began to take off. We were getting over 50,000 downloads by late 2018, and we were getting enough money in to actually get paid for doing it.”

Christine Schiefer, host of And That’s Why We Drink and Beach Too Sandy, Water Too Wet: “We had already found success with a paranormal and true crime podcast, And That’s Why We Drink, which I launched in January 2017. In autumn 2018, my partner Alex and I launched Beach Too Sandy, Water Too Wet, a podcast featuring one-star online reviews, inspired by reading online reviews of the Chippendales after our own experience of them. I noticed that between the two, the barrier to entry had been significantly reduced thanks to the new podcast apps like Anchor, which allow users to record and upload episodes straight from their phones. Anchor also helps you make money through sponsorships. I think the apps have helped drive the growth in podcasts in the last few years.”

Miceli: “The show has become like a family. Or a cult. Or a cult family. We’ve ended up making friends with all these listeners and we have these parties here on the farm for my birthday… every couple of years we throw a ‘Dawnapadrewza’. It’s like a cult of misfits, it just works.”

Jeyes: “When we launched the London Podcast Festival in 2016, it was immediately a huge success. I programmed the comedy at Kings Place in London and really got the idea back in 2010 when we invited a New York podcast called The Complete Guide to Everything over to do a live show. It sold out incredibly quickly, and to come all the way from America to start a show in London when you’re not professional comedians is quite remarkable. Someone who came in 2016 said, ‘The London Podcast Festival attracts a special kind of nerd’. I think that’s true. You have an intimate relationship with the podcaster before you turn up, it’s like a one-sided friendship you’re turning into a two-sided friendship when you meet them.”

Miceli: “People have written in and said that the show gave them a reason to not kill themselves. I’ve gotten that message more times than I want to even tell you. It’s sad that somebody felt so alone that a voice on a podcast, or people talking into the void on the internet, actually saved them. I know that we’ve actually changed people’s lives. I know that because I’ve seen it. It’s blown my mind, to tell the truth.”

By March 2018, 50bn podcast episodes had been downloaded or streamed from Apple alone. The figure was striking for the sudden increase: in 2016 it had stood at 10.5bn, rising to 13.7bn in 2017. These are numbers that suggest, says Damian McKeown, a tipping point for podcasting — and there are others to back up the impression. The number of new podcasts is now almost doubling every 12 months (in 2017, there were 11,000 new titles; in 2018, 21,000). Fortunately for publishers, the audience for podcasts is also growing, at a rate of between 34 and 37 per cent each year.

There’s another reason for the gold rush, though. Up to two or three years ago, software developers had been unable to come up with anything that reliably turns speech into written words. A new generation of algorithms is changing that, which is why you may have noticed more transcription apps becoming available. That technology means that podcast episodes can now be turned, in seconds, into the sort of lovely, searchable text that search engines like. You’ll soon be able to use Google to search for specific content in podcasts, and the results will give you not only the title, but the moment in the episode when the subject is mentioned. Easier for you to find podcasts; easier for advertisers to find you.

Curry: “Steve Jobs asked me, ‘How do you plan on making money with this stuff?’ I said, ‘Well, on the stuff itself we don’t plan on making any money, but I do see a radio model. That may be advertising, it may be something else, a hybrid, I’m not sure’. Afterwards, as a kind of thank-you, he said, ‘Look, I’ve called [venture capitalists] Kleiner Perkins, and you have a meeting with them, so you can go and see if you want to raise some venture money from them to start your company, to fund it,’ which we did.”

Miceli: “There’s so much money in it now. When we were first doing this we were so excited because we got an advertiser for $200. And now… I just saw a list of [stand-up comedian, host of The Joe Rogan Experience] Joe Rogan being worth $25m. I think that’s fascinating that you can make a huge career from actually making podcasts. The industry wasn’t even here 15 years ago.

“One thing that I think has changed is companies are more willing to spend money on somebody and not be scared of what the results are. Years ago, we had this whole idea and we called it ‘The Come and Squat Tour’, and we were gonna buy an RV and travel around the United States and go to listeners’ houses and basically interview people. The gas was all gonna be covered by a major oil company. We got the RV, but two weeks before we were supposed to leave, someone there listened to a show where I think I was talking about my pussy or something, and they freaked out and were like, ‘We cannot sponsor somebody that talks about their pussy! It’s porno! Our brand will be affected by this’. They pulled the whole thing. But I think now companies are more like, ‘We don’t have to be so worried, our brand image doesn’t have to be so squeaky-clean perfect and stuff like that’.”

Ratcliff:“The thing about advertising in digital media is that while you can count the engagements with something, you can’t know how deep that engagement is. But with a podcast you do know, because nobody puts a podcast on, and puts their earphones in, and doesn’t listen to it.”

McKeown: “Why are big companies spending money on podcasts? One reason has to be the audience and the ads. Out of all media, podcast ads are the least likely to be skipped — 20 per cent of adverts in podcast ads are skipped, compared to 24 per cent in, say, newspapers. They’re also four times more likely to be remembered than ads on any other digital media. Spotify Premium users are, by definition, ad-avoiders — maybe Spotify is thinking podcasts are a way of reaching them.”

Brenda Salinas Baker, content strategist at Google Audio: “Now that podcasting is more of an established medium, people are wondering, ‘OK, what happens next?’”

Glass: “This is an odd and ridiculous moment for podcasting, but a hopeful one, too. You know, I feel like there’s still so much that this medium can do that nobody’s done. Like, it’s still an undiscovered country.”

Baker: “Just one thought is, although podcast-listening has been a solitary activity, we’re now seeing people start to gather around smart speakers like people used to gather round radios. So you might see more podcasts for communal listening.”

Collymore: “In 20 years’ time, young footballers will get back from training on a Monday, stick their iPhone in its holster, press a button, say whatever they like, use an algorithm to edit it down and publish it on their own channel by tea time. It’s the antithesis of what I grew up with, when a newspaper could write anything about you and there was no right of reply. It’s going to be a media democracy.”

Esther Ainsley, London Podcast Festival: “There’s a very close relationship between podcasters and audiences at the festival because they support each other. It feels less like audience-and-performer and more like networks.”

Mann: “Helen [co-host Zaltzman] says the big change that’s happened during our podcasting lifetimes is in 2007, if you said you’re doing a podcast people would come up and say, ‘What’s a podcast?’ In 2014, people would say, ‘Oh, I love podcasts. Tell me more about yours’. And in 2019 they say, ‘Oh, I’ve just started a podcast! Do you want to listen to it?’”

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox