On a recent video call from his South London home, Shabaka Hutchings is running through his ever-growing to-do list. There’s the record label he just launched; the solo album he’s planning; and the book that he’s writing. Then there’s the new album, which he’d recorded just a few weeks earlier. Around all this, there’s the practice: when he’s not blowing the saxophone or clarinet in a nearby community centre, he plays them in the woods, to keep his sound sharp and body active during the UK lockdown. “When you play in nature, it doesn’t echo,” he says. “Plus it’s good to breathe in the fresh air. It makes me a better player.” In a rare moment of rest, he started watching Breaking Bad, but even that gave way to more work: while streaming the show, he’d sketch drawings for potential merch.

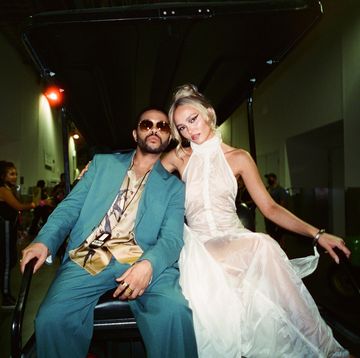

Though his schedule sounds intense, in conversation Hutchings is anything but. Wearing a green knitted kufi hat and black-rimmed glasses with circular frames, he smiles widely and exudes an almost childlike exuberance when talking about his music. A simple “how ya been?” can lead to sidebars about some new creative wrinkle he’s added to his sound. That vigour has served him well so far: through critically acclaimed albums as the leader of Shabaka & the Ancestors and Sons of Kemet, and as one-third of another band, The Comet Is Coming, he’s become a cornerstone of jazz and experimental music in the UK and the US.

Hutchings is at the forefront of a local jazz movement that gathered steam about four years ago and quickly gained international buzz. Though he’d been a talked-about player and session musician, he broke into bigger circles somewhere around 2016, when Channel the Spirits, the debut album from The Comet is Coming was nominated for a Mercury Prize. Then, the Ancestors’ first record, Wisdom of Elders, earned critical acclaim in the US and, in the UK, props from the likes of Gilles Peterson, the highly respected DJ and tastemaker, who released the LP through his Brownswood Recordings imprint. In 2018, Hutchings served as the musical director of the label’s We Out Here compilation, which featured some of the hottest players in the young UK jazz scene.

Wisdom of Elders arrived at a time of intense racial and political tension in the States, and just a few months after rapper Kendrick Lamar and saxophonist Kamasi Washington released the sonically ambitious To Pimp a Butterfly and The Epic, respectively. Black listeners needed to heal, and those albums, along with Hutchings' LP, perfectly captured the tenor of the moment. Soon after, Hutchings’ name started showing up everywhere in the UK and beyond — on jazz drummer Makaya McCraven’s expansive Universal Beings and on vocalist Moses Sumney’s genre-bending grae.

Even as journalists wrote flattering pieces about the resurgent UK jazz scene, Hutchings and his contemporaries shrugged off the description: sure, they were happy that people were coming around to what had been emanating from the scene, but they were making music that encompassed various ideologies. To them it was just good music that didn’t need tags. Musicians like Hutchings, saxophonist Nubya Garcia, drummer Moses Boyd and tuba player Theon Cross were making jazz for people who maybe weren’t familiar with the genre — at least not in this form. Their sounds blended everything from grime and drill, to soca, Afrobeat and reggae, and tapped into a younger audience who only knew jazz from their parents’ old vinyl collections. These were musicians who grew up studying Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock, but also had an affinity for contemporary rap and R&B. So it wasn’t jazz in the traditional sense; their arrangements worked equally well in smoky old nightclubs, after-hours dancehalls and open-air festivals.

Hutchings had been around a little longer than most, gigging in all kinds of venues throughout London and Birmingham, sharpening his craft by performing with any and everyone as a way to build his name. In turn, Hutchings has earned a reputation as a musician’s musician, perhaps the hardest-working player in the scene. His sound was transcendent, a piercing, blustery wail, not unlike those of Pharoah Sanders and Albert Ayler in the late Sixties, but with a rich melodic texture that conveys various moods. And because he’s in three bands and toured constantly, he’s become the most visible jazz musician in the UK, his name popping up in the credits of seemingly every essential release and on the bills of every you-had-to-be-there show.

On 14 May, Hutchings' Sons of Kemet will release what might be the group’s timeliest album, Black to the Future, which was recorded last year after the death of George Floyd in the US and the global protests that followed. The LP arrives as Derek Chauvin, the police officer who suffocated Floyd, was recently found guilty of murder and manslaughter, as the country once again reckoned with intense racial divides. In April, Daunte Wright, a 20-year-old Black man, was shot and killed by then-officer Kimberly Potter during a traffic stop in Minnesota, not far from where Floyd died. Days later, video surfaced of Chicago police shooting Adam Toledo, a 13-year-old Mexican American boy, despite his hands being raised.

The timing of his album’s release isn’t lost on Hutchings; racism and police brutality are so ingrained that similar incidents will likely happen again. “The images are striking, but the killings in and of themselves aren’t surprising,” he says. “The issue has been there, but it hasn’t been visualised the way it has been now.” The album itself isn’t meant to solve the crisis and Hutchings isn’t a political musician; instead, it celebrates the Black experience — through spoken-word poetry, Afro-Caribbean dance and New Orleans Second Line — as a way to inspire listeners to come up with their own solutions: “What is it to be Black in any of the centres of oppression? We have to bring the issue to the surface and find a way to move forward with it.”

Hutchings was born in London and moved to Birmingham with his family as a toddler. When he turned six, his family moved back to their native Barbados, partially because of the racial tension that young Shabaka experienced in Birmingham classrooms. “My mother was a schoolteacher and she could see what was happening to young Black boys, and she could see the same thing happening to me,” he says. “I was finishing all my schoolwork early because it was too easy for me. Then I’d start talking to children and the teachers would say I was being disruptive. It was just that the teacher didn’t know how to deal with someone who was ahead academically at that level.”

Even at that age, he remembers, young Black students socialising in groups were labeled as gangs. “So then my mother was like, ‘Why am I putting my son through a situation where I can see the end result?’” he says. “I would’ve had to struggle through elements of race, whereas if I were to go to the Caribbean, I would still have to struggle, but at least the same type of racial factors wouldn’t be any issues in the same way.” At nine years old in Barbados, he was given a clarinet to play in music class. “I enjoyed just what it was to make music,” he says. “I enjoyed every aspect of the instrument, of playing it. Every chance I could get to play it, I would.” It wasn’t until he got a little older, and the question of ‘What do you want to do as a career?’ arose, that he started thinking about a path in music: “I knew that it would involve the instrument, because that was me. There wasn’t any differentiation in me doing music and me as anything else. It was just all a part of the same thing.”

Musicians in Barbados didn’t tether themselves to genre. If you played the clarinet, you simply played the clarinet; you weren’t a ‘jazz’ or ‘classical’ clarinetist. “The island is so small that you don’t have the luxury of being a specific musician,” Hutchings says. “There’s that culture of musicians being explorative.” Hutchings went back to Birmingham for grammar school at age 16 to complete his A levels; he didn’t become interested in jazz until he saw the saxophonist Soweto Kinch play a gig. It was the first time he saw a younger performer blending jazz and hip-hop in a fluid way. For the next two years, Hutchings cut his teeth performing with Kinch at weekly jam sessions and listening to jazz records at his house. He also honed his work ethic. “I think at an early age I recognised what needs to be done,” he says. “For me, it was a matter of ‘If I play this piece well enough, if I practice it every single day, from slow to fast, then it’s learnable.’”

During the day, Hutchings poured everything into studying classical music at grammar school, then at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, waking up every day at 6:30 and practicing for three hours. Hutchings was naturally a hard worker who didn’t prioritise a social life over his music studies; as he saw it, he was supposed to sacrifice everything to be the best possible artist during his four years studying. But there were bigger issues at play. “If they could’ve kicked me off that classical course, they would’ve, because they already weren’t happy with me playing classical music and jazz,” Hutchings says. “They’re like, ‘What are you gonna do about this jazz problem?’ I had to practice the classical stuff enough to make them get off my case and so I could go, ‘Look, if I’m not playing the classical stuff well enough, then you can talk to me. But if I’m doing it, then what I do in my other time is my business.’”

At night, Hutchings went to jam sessions around town and absorbed all the music he could. That’s where he got another form of education: playing with established musicians who weren’t impressed with his skills.

“The jam sessions were sink or swim, you’ve just got to know what you’re doing,” he says. “You have to learn the changes, you have to learn the jazz vocabulary, and learn how to navigate those harmonic structures. The jam sessions taught me that it takes a load of work to even get to the stage where you can start to learn what jazz is about.” Hutchings remembers the time (a “traumatic event,” he says jokingly), when, as an 18-year-old student in Toronto for a jazz conference, he went to a jam session one evening. He was playing a tune that he got lost in; when he stopped and opened his eyes, the pianist laughed at him openly. “I knew he was laughing at me because I didn’t know what I was doing,” Hutchings recalls. “I knew the intention behind what I wanted to get on a broad, emotional level, but there were a lot of elements in my fingers that were going around the instrument in a gestural way.” Nowadays, though, he leans into the emotional side of his playing. “I’m trying to get a point where I don’t know what I’m doing,” he says. “The spirit comes when you let go and you’re guided by some other considerations.”

For some jazz fans, the genre died in the late Sixties, when Miles Davis plugged in his trumpet and Herbie Hancock eschewed the genre for funk. But jazz is evolution, not tradition, and though this new generation of players is still connected to its roots, their innovation is to mix in something that speaks to them. Artists like Hutchings, Georgia Anne Muldrow, Robert Glasper, Terrace Martin and Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah are blending the genre with hip-hop, thus making it more palatable for younger listeners. Hutchings has spent his entire career trying to break down the barriers between jazz and the music he loved as a child, opting for an amorphous sound that’s tough to classify. Just take the most recent Sons of Kemet albums as examples: Black to the Future is a dancehall record evoking seaside two-stepping on the beach; the band’s previous album, Your Queen Is a Reptile, was an acoustic stomp more suited for a Caribbean carnival. Hutchings revels in the mystery; that you can’t fully identify what’s going on in the music is an added bonus. That’s his way of getting listeners back to the truest function of music: to just enjoy it without the manmade classifications that separate the art.

He’s spent the past decade developing this practice. Cross, a tuba player in Sons of Kemet, met Hutchings in Tomorrow’s Warriors, a local jazz programme that develops young musicians. Years later, the two briefly worked together in a band called Brass Mask until Hutchings left to lead his own group. Before Cross joined Kemet, he’d see Hutchings playing in all kinds of venues — from Cafe OTO, which books psychedelic jazz and avant-garde music, to Ronnie Scott’s, a more traditional jazz spot. “They all reflect different parts of what he’s trying to say,” Cross says. In Kemet, Cross and Hutchings formed a connection as children of Caribbean descent: “My strength came from adding a different, rhythmic cadence to it. It was more a conversation of, ‘Your sound is right for the band and it’s where I’d like to go.’” Hutchings “brings a thoughtful mastery to his craft,” Cross adds. “Everything he does has intention, whether it be his unconventional rhythmic styles or conceptually attaching his thoughts to whatever music he puts out.”

Garcia and Hutchings played a few local shows together and became friends on the road. “We kept running into each other, bonding about how tired we were, but how excited we were to play that night,” she says. “Then from there, we’d be in so many of the same spots.” As Hutchings ascended, he brought Garcia in to bigger gigs. “Shabs has always brought me in,” she says. “I feel like we’re playing more and more together as the years go on, which feels really great. I learn a lot from him.”

Producer Dan Leavers often tells the story of when he first played with Hutchings. He and his bandmate Max Hallett were performing a show when they noticed a “tall, shadowy figure” looming on the side of the stage with a saxophone. Hutchings wanted to play with the group; Leavers nodded him onto the platform. Once he started playing, “the crowd kinda kicked off,” Leavers recalls. Soon after, in September 2013, Leavers, Hallett and Hutchings went to the studio to record their blend of cosmic jazz electronica; The Comet is Coming was born. “It was fun to bring him into our world a little bit,” Leavers says. The Comet’s music sounded nothing like Kemet; it was much darker and apocalyptic. It still scans as jazz in a way, but between Hallett’s pounding drums and Leavers’s spacey electronics, one could also call it rock. “He could be shredding something and it sounded more like an electric guitar,” Leavers says of Hutchings.

But if there’s one knock on him, it’s that he doesn’t know how to sit still. While that ingenuity has helped make him a star, he also runs the risk of burning out without proper life balance. Before the pandemic, he would spend most of the year on the road, performing with one band while writing music for one of his other bands backstage or in hotels. “I’ve been on tour with him, and seen him writing melodies on manuscript paper,” Leavers says. “But you see the results. Shabs works harder than most people I know.” To maintain that productivity, he eats properly and tries different breathing techniques to sustain his energy. “Whatever strategy he can use to be at peak performance,” Leavers adds. “Don’t underestimate what’s going on behind the scenes with Shabaka.” Still, there’s the notion that Hutchings is reconstructing himself just to be a better artist. “I was worried about Shabs,” says Siyabonga Mthembu, the lead vocalist of Shabaka & the Ancestors. “Shabs has to learn to be human.”

Following the Wisdom of Elders release, the group spent several months on the road due to the LP’s sudden popularity. “I was tired and I looked at Shabs like, ‘You do this all the time?’” Mthembu says. “He needs friends like us who ask that question. We were put in Shabs’s life to look after him the way he looks after us.” Still, he understands why Hutchings operates the way he does: he came up in competitive schools with people who didn’t look like him. As a gifted Black male, first with teachers who placed unfair labels on him, then others who didn’t see his jazz as equal to classical music, he’s had to work extra hard to debunk preconceived ideas of who he is as a person and musician. “He’s an athlete,” Mthembu says. “He’s a rare breed; beyond his own personal genius, he’s searching for something collectively. He leads with a sense of selflessness.”

Despite all the acclaim, Hutchings doesn’t see himself as the guy; he simply follows his curiosity and trusts his gut, letting it lead him to unforeseen creative places. There’s been no flashpoint moment in his career; instead, it’s been a snowball effect – one gig leads to another, one studio session becomes two, and this person drops his name to someone else. “I think with all the playing I’ve done within the scene for so many years, my name gets pushed to the fore,” Hutchings says. “This part of centring myself, that’s been happening for a few years.” He’s hit a stride recently, though, and with all the lauded work being put out, Hutchings now commands bigger fonts on marquees throughout the world.

Not that he’s concerned with that. When I called back recently to check in, he tells me of yet another new hobby he’s taken up: the MPC beat machine. Now Hutchings is learning how to make instrumentals like the famed hip-hop producer James 'J Dilla' Yancey. “And I won’t need to sample since I play my own instruments,” he says through a smile. “I’ve been reading the manual and watching YouTube tutorials. I’m trying to be a producer.” Breaking Bad will have to wait.

Black to the Future by Sons of Kemet is available from 14 May. Buy it on Bandcamp