Jeff Bezos would like you to know that he has dreamed of going to space ever since he was a little boy, ok? That’s the first point the new Amazon Prime documentary Shatner in Space, now streaming, strives to make. The next two are: Jeff Bezos loves Star Trek, and Jeff Bezos’s goal to launch earth’s trash into orbit is a noble and worthwhile one, respectively. Also, there's a minor additional point, which is that Jeff Bezos has been working out, but that’s neither here nor there. After all, this is a documentary about William Shatner, right?

At least that’s how it was advertised. A press release touting its premiere bills the documentary as a “one-hour special documenting William Shatner’s life-changing flight to space.” Sadly, Shatner in Space is more of a heavy-handed stroke of Jeff Bezos’ ego than it is a unique character study of the captain who has indeed lived long and prospered.

The film begins innocently enough, with a touching string of scenes featuring the actor rhapsodizing in the present about outer space spliced alongside snippets of him as a young Captain Kirk in old Star Trek episodes. But within three minutes, Bezos makes his first of many appearances to take Shatner, and by extension the audience, on a tour of the Blue Origin offices.

Before a fortuitous meeting brought them together (we aren’t told where or why this meeting occurred), Shatner says he had only read about Jeff Bezos in the press and had the same impression of him that many other people have: rich guy who started Amazon and is looking for a new way to spend his money. “But little did I know,” says Shatner during an on-camera interview, “he’s had this dream all along.” See everyone? Bezos’s penis-rocket is not some weird, intergalactic mid-life crisis. It’s a childhood dream come true!

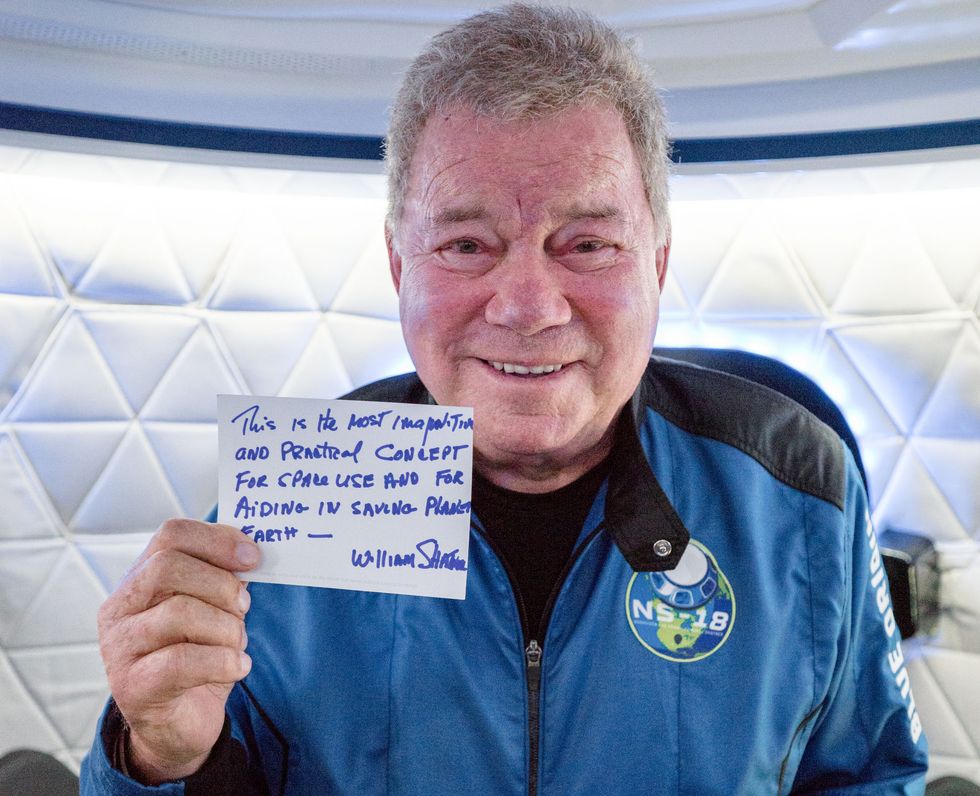

It gets worse. Bezos then proceeds to explain to Shatner why he thinks it’s important for humans to be able to get to space safely and inexpensively (the documentary does not define exactly what “inexpensive” might mean to Jeff Bezos, but seats aboard Blue Origins’ crewed flight in July went for a cool $28 million). The camera sticks around to capture Shatner reciting Jeff Bezos’ vision for Blue Origin back to the CEO verbatim. “What noble ambitions” says Shatner after nailing the assignment. “I can get behind that!”

Some of Bezos’s banter in Shatner in Space is so defensive, and the scenes so inauthentic, cynics might wonder if Amazon used the ever-affable Shatner as a way to pass this special off as a legitimate form of nonfiction entertainment rather than what it really is: a long, nauseating attempt to improve the image of Bezos and Blue Origin.

Coincidentally enough, Shatner in Space is not the only documentary about the corporate space race to premiere on a streaming giant recently. Countdown: Inspiration4 Mission to Space, which was released in September on Netflix, detailed the lead-up to the SpaceX launch of the first all-civilian mission into orbit.

Similar to Shatner in Space, Countdown comes across more like the extended cut version of a Superbowl ad than it does a critical docuseries. This is all the more frustrating when you consider the historic event filmmaker Jason Hehir was invited to film. Four civilians embarking on a three-day journey that will take them beyond the International Space Station should’ve made for a great film. Instead, thanks to an egregious amount of aggrandising about SpaceX and the tech industry’s takeover of space exploration, Countdown failed to live up to the promise of its source material, let alone present an authentic picture of the ongoing debate about the merits, or lack thereof, of private space tourism.

Both works are advertised by their respective streaming platforms as works of nonfiction, but, and this is important, neither falls in line with what the typical viewer might expect from a documentary—even as that term is applied to an increasingly diverse amount of works. Across the nonfiction film industry, some critics are beginning to take issue with the widening distance between what documentaries claim to be and what they actually are.

“What looks like a documentary can mean many different things,” said Rob Swartz, senior vice president of the cable network Reelz, to the journalist Danny Funt. Funt interviewed Swartz for an article in the Columbia Journalism Review about the decline of journalistic rigour in documentary filmmaking. In his piece, Funt argues that as streaming services' demand for documentaries soars, traditional journalistic restrictions are being abandoned and replaced by looser, more PR-friendly principles.

Looking at Shatner in Space and Countdown: Inspiration4 Mission to Space, it’s easy to see evidence for Funt’s argument, but not everyone agrees to what extent strict, time-honuored documentary filmmaking practices (like separation between producer and subject) even matter anymore—especially in today’s era of on-demand content. Summarising the opinions of several producers he spoke with, Funt writes “editorial rules only make sense for documentaries about grave political matters.”

So does it matter then if Shatner in Space and Countdown:Inspiration4 Mission to Space are actually infomercials sheltering under the oversized umbrella term “documentary?” The answer to that question will depend largely on your politics.

The mission of each piece is obvious: to curry favour for their subject and endear the general public to their respective plans. Musk wants to force all of us to live on Mars. Bezos wants to pollute the Milky Way. These are outrageous endeavours of dubious worth, but we the people can only give our rose—or, in this case of extreme capitalist competition, our consumer preference—to one suitor. So the CEO who makes the most convincing case for himself, in real life and on screen, will be the one to win the people's vote and, in turn, the influential government contracts necessary for building his corporate space colony.

If you’re okay with that situation then Shatner in Space and Countdown probably won’t offend you. But if you’re at all skeptical of the privatisation of critical government functions—and historic events like the great recession of 2008 suggest a little concern might be warranted—there's a good chance you will find the incomplete and oversimplified narratives presented in these propaganda documentaries a little disturbing. If nothing else, they indicate the sketchy lengths tech titans might go to to amass power in our new cosmic frontier.

Abigail Covington is a journalist and cultural critic based in Brooklyn, New York but originally from North Carolina, whose work has appeared in Slate, The Nation, Oxford American, and Pitchfork