Call me Don. I don’t get called Sir Don often but I feel uncomfortable when I do. It’s hard to get used to when you weren’t born into it.

Happiness for me is standing on an English landscape in the freezing cold, photographing in a blizzard. That’s the ingredients for a really super day. I’ll drive 300 miles for that.

It's essential for families to be close. If we were more like Italian or Mediterranean families we would be, but in England we’re austere about family. Slightly non-trusting. I love my family. I think they know it and they know that I like having them around.

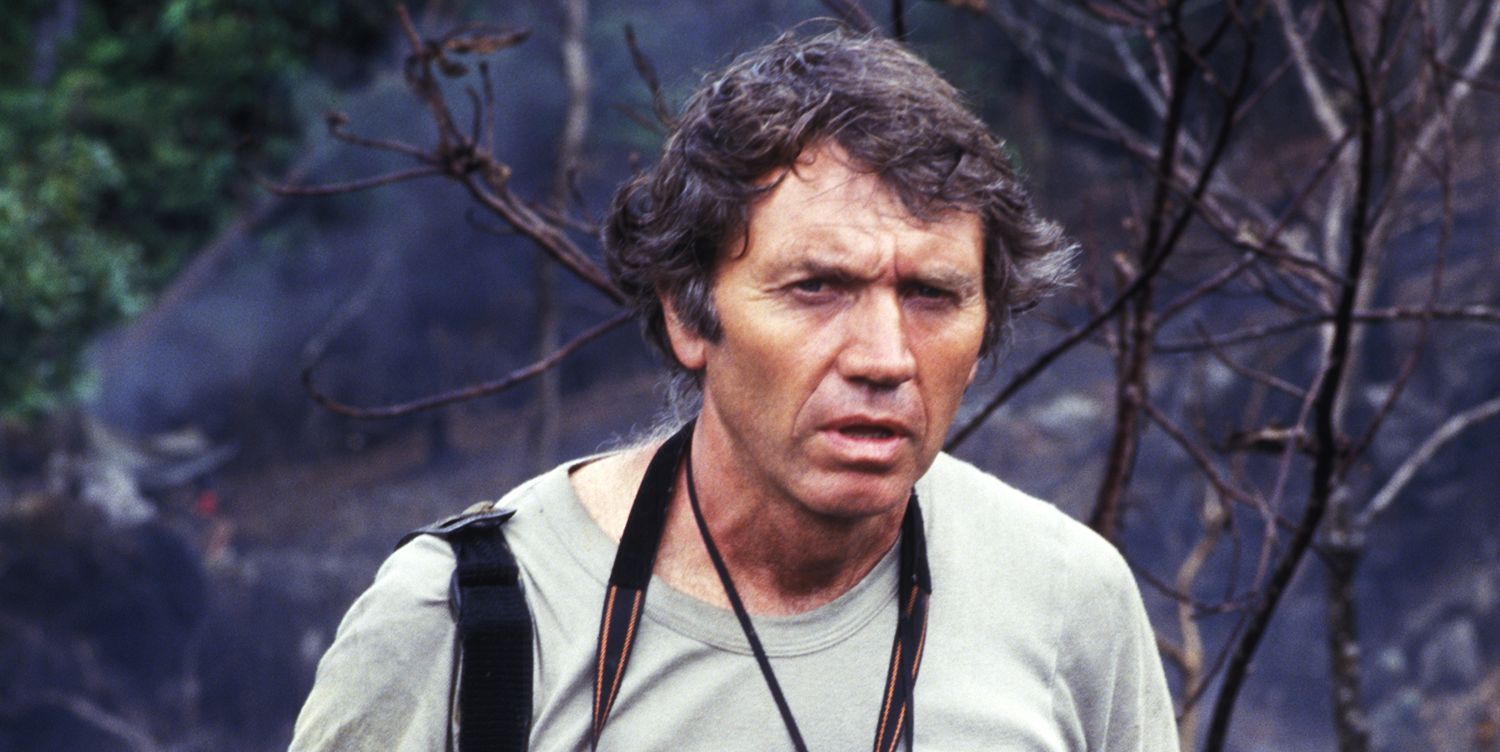

I was in Mosul a couple of years ago. A suicide bomber was coming and everyone pushed us in the house. There was a mighty explosion and I thought, "Christ, a bloke of my age, 80, in a battle at Mosul." I am not a daredevil. I am a very curious human being. I don’t want to be left out of a subject I know a lot about, and that's war. I want to be there.

As a young man, I didn’t like beer so I’ve never been a big drinker. I didn’t smoke and never took drugs. These days, I’m a legal drug addict because of my heart bypass operation.

My father died when I was 13. My mother was the male of the family, very strong and powerful, dominating. I probably took some of her organic strength, inherited her genes. Her right hand used to come frequently into my face. I never hit my children.

In a way, I’ve had three families. My first wife Christine died. We had three children. Then I had a child with a woman who didn’t marry me. I’ve got a younger son, Max, with my wife, Catherine, who is 30 years younger than me. I’ve been a bit of a bad parent because in my kind of journalism, you’re constantly travelling, abandoning your family. The irony is Catherine is a travel writer and this year she’s been travelling more than ever. The boot’s on the other foot. I understand it can’t be nice for a wife to have a husband who is never there.

In Cambodia, I took a picture of two dead Khmer Rouge tossed in a pit. I was running across a battlefield with a group of soldiers who were testing their firepower. I was told not to go by a commander and we nearly got wiped out. I ran away and hit the ground, which was water: a paddy field. I slithered until I hit dry ground and then ran like shit — I was a great runner when I was younger — zigzagging because there was a sniper. When I got back, one of my cameras had a bullet hole. I’m not sure whether it was hit while I was running or lying down. That was the day before I found those two dead men in the pit. I could have been one of them.

I love blackberry picking. Total mental release from stress and worry and stuff.

The most valuable things we own are human flesh and human existence, and we trash them as if they’re unimportant.

You must never turn your back on technology, even though it might be very tempting to do so. I don’t really know how to use my phone properly, though I’ve had it for years. I don't use a computer. I don't know how to get a railway ticket from the automatic machines. I've been wilfully disobedient in not learning and it's put me in trouble.

When I became known for my work, it was uncomfortable because I was drawing attention to myself. I’m not meant to be on that side of the camera. It also meant I had to double the output of the pictures in terms of intensity. Dramatically, they had to get better. It’s like winning a gold medal in the Olympics. You want to get the next gold medal, the next one and the next one. I wanted that, not the fame.

Do I believe in God? Not really. I believe there’s something out there that I mustn’t disrespect. I’ve got a fear of killing animals. I mean, I killed the rats that got into my house, but if I drive through the country lanes and kill a bird, which I did three years ago, I feel incredibly bad. It’s having seen so much death. I think if you encourage death, death will come to your door. It will come for you.

One of the great regrets I carry is leaving Christine. She died the night before my eldest son’s wedding a couple of years later. She and I didn’t really make up. I went to apologise and be with her in the last days of her struggle for life. It was a tragedy. When it was all over, the woman I went back to kicked me out. I actually saw her recently, for the first time in years. She was trying to be nice to me and I didn’t really care. I didn’t have the slightest feeling for her. When Christine was dying, I thought, "Well, fuck it, I’m not going to abandon this woman who gave me three lovely children." Nothing to do with relationships, it was to do with this woman dying. I had to be there and let my children see me be there. I did the right thing. I don’t give a fuck about being kicked out of the house, because I went with all kinds of beautiful women. Then I married a beautiful American woman which was a disaster. Finally, I married Catherine and she’s incredible.

I’m making a film for the BBC. Revisiting my old locations, in the north. Bradford, west of Hartlepool and places like that. We’re trying to photograph in Parliament Square but they won’t let us. So much for democracy.

I used to tell lies. Constantly doing shifty kinds of things to save the work. You don’t want to work and work and lose all that film. It makes me sound deceitful, but it wasn’t. It was what I call professionalism.

I’m 83 and my body is shutting down. But I won’t have it. I can’t close my right hand any more because of arthritis. My feet have got it, too. I’ve been to Syria this year. I’ve been to Chile and Los Angeles. I’m a bit like King Canute, constantly pushing back the tide. I just want to get a few more miles down the road with Max — he’s 16 but bigger than me — so he remembers me when I’m gone.

Tate Britain hosts a Don McCullin retrospective from 5 February to 6 May.