The first time I saw Spring Breakers, writer-director Harmony Korine’s seedy beach noir currently celebrating its tenth birthday, was as God intended: on my friend’s PlayStation 3, either before or after a night in various bleating, lurid bars. What we saw onscreen felt familiar enough but warped, like friends’ faces on the third night of a bachelor party. Is this what pleasure does to people? The movie makes its intentions clear with its opening montage—the only thing more depraved than the slow-motion images of half-naked beachgoers pouring beer on each other is the Skrillex drops soundtracking them.

Korine had to that point specialised in provocation. After writing the mid-90s lightning-rod Kids, which follows a group of New York teenagers as they skateboard, do drugs, and have sex with varying degrees of consent, Korine turned his attention to middle America with the elliptical Gummo, full of dead cats and spaghetti. That film and its immediate successors established Korine’s reputation as an artist exploring the far contours of American decline, the way its boys were goaded toward violence and its elders lay breathing and forgotten in back-rooms.

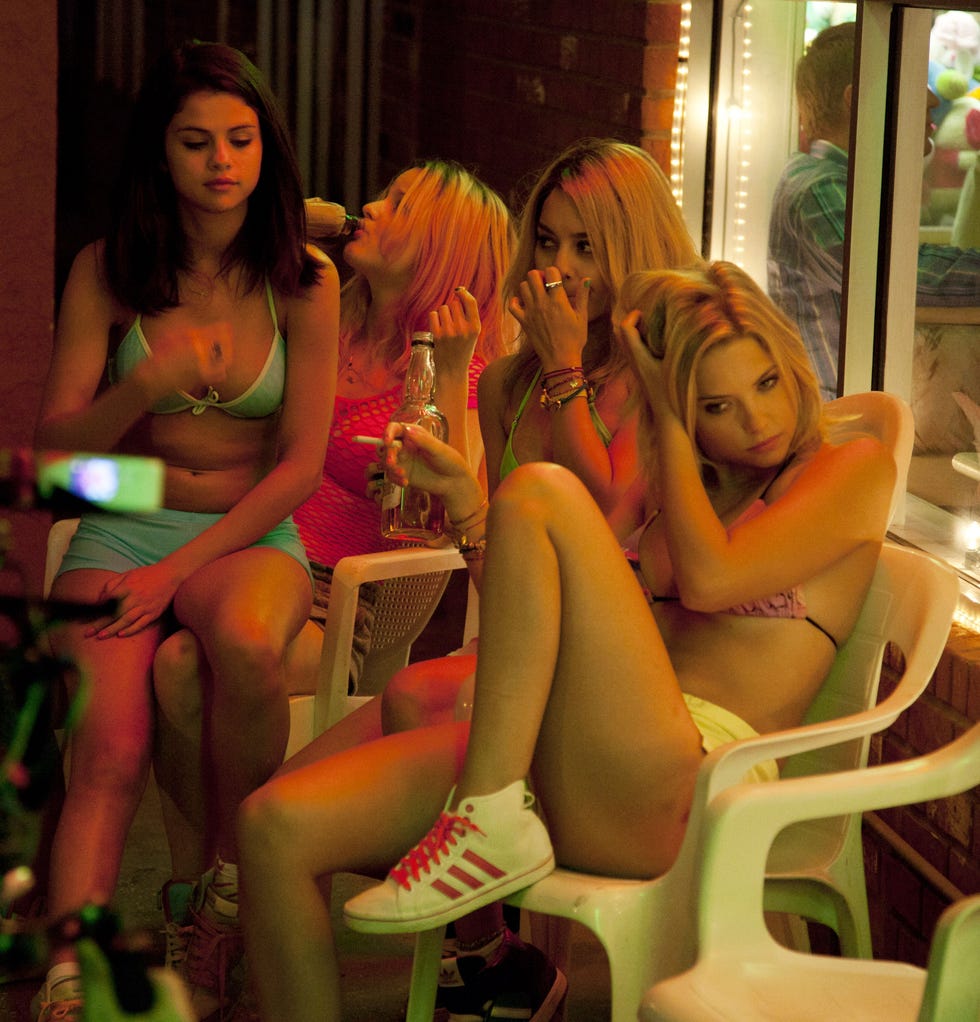

But it was when Korine viewed his familiar obsessions through the prism of young women rather than young men that his capacity for shock became most potent—and artful. Spring Breakers felt like an unlikely pop pivot upon release, but looks increasingly like his masterpiece, and one of the finest neo-noirs of this millennium. It could not have been cast better. Vanessa Hudgens was fresh from a trio of High School Musicals; Selena Gomez had just wrapped her fourth season of Wizards Of Waverly Place; Ashley Benson had backflipped from the fourth Bring It On to a role in Pretty Little Liars. The director’s wife, Rachel Korine, plays the fourth part of a quartet of college students who see a blowout week in St. Petersburg as a necessary escape from their dead-end college town and see robbery as the only way to get there. They wield squirt guns with deceptive authority at the denizens of a diner in a heist we watch take place from the getaway car, nervously listening to Nicki Minaj.

Once in St. Pete, things go increasingly off the rails. Korine, who has said the movie was a way to vicariously live the sort of spring break that he was too busy skateboarding to enjoy, embraces almost improvisatory setpieces. A young man rips a bong with a turkey carcass on his head. The on-screen Korine lays on her back in a bikini taunting juiced-up dudes in a scene that ripples with sexual menace. Coke comes out and Gomez, seeing the way things are headed, bounces; so too does Korine. James Franco, as the rapper Alien, is introduced, and in the film’s greatest perversion, at one point he drinks a 32 oz bottle and an 18 oz can of Natural Light at the same time. Later, Hudgens and Benson force him to perform fellatio on a gun, much to his delight. The contours of a heist film take shape—Gucci Mane is involved—but the dialogue establishing this largely happens offscreen, like it’s echoing in from another movie. Many people end up dead, but Hudgens and Benson emerge with bags of cash, whispering in the closing moments the immortal prayer, “Spring break forever, bitches.”

Alas, spring break was not forever. Everyone’s career caromed in different directions, almost immediately. Hudgens and Gomez pivoted to cosier fare—cooking, Christmas movies, Steve Martin. Benson finished a run with PLL and took exactly zero additional movies in which she does blow off a naked woman. Korine took seven years to release a follow-up, 2019’s shaggy-dog shrug Beach Bum, which treated middle age as a sort of timeless parody, as if everything after adolescence was a pointless blur. He and Rachel, who retired in 2015, have two kids. Gucci Mane went to jail and came back sober, swole, and settled down. Franco’s trajectory is entirely different—a series of sexual assault allegations, beginning in 2014, gathered steam, eventually sending him packing from Hollywood.

In some ways, this makes the movie a time capsule: that any of these stars would ever be in this position, in these configurations, and also listening to Skrillex, is now impossible to consider. Strange, too, to think the movie was only the third release by the studio A24, which would go on to become a powerhouse producer of high-concept genre fare (including newly minted Best Picture-winner Everything Everywhere All At Once). The film feels like an early thesis statement of what made the A24 style so refreshing, splitting the difference between Terrence Malick and Michael Bay in a way that neatly reflects then-relevant conversations about “vulgar auteurism.”

But viewed 10 years later, our understanding of every artist’s career arc only adds to the movie’s power, its feeling of a weekend that stretched on too long and forced everyone involved into increasingly higher-stakes party activities. Hudgens is particularly fearless, her character (who one early onlooker says “got demon blood”) relishing each step into an underworld of drugs, guns, and money. Perhaps no scene is more haunted than the famous Britney Spears singalong, at the time a trashy, pop-art nod but today freighted with our understanding of how little control the star had over her own life at the time. The unironic paean to the original Disney princess crystallises the feeling of Spring Breakers as an act of rebellion from its young stars.

The girls refer to their trip alternately as “a videogame,” “a movie,” “a break from reality,” a nested world in which they do not wear anything besides bikinis even when standing before a judge. They speak repeatedly of their fear that their dream might end, like imaginary friends desperate to not be forgotten. But of course, vacation, like youth, does end. When I watched the movie recently, it was on my laptop with earbuds; I didn’t want to wake anyone up when the beats dropped. What remains of youth are pictures and music, both of which can be transportive, and which burst from Spring Breakers like few films of its era. Which is to say that it does not matter when or how you watch it. You will smell the vodka. The kids we see in throes of idiot glee flipping off the camera look immortal, because, in a way, they are. Spring break isn’t forever, but Spring Breakers is.

Clayton Purdom is a writer and editor based in Shaker Heights, Ohio. As well as Esquire, his writing on culture and technology has appeared in Rolling Stone, GQ, and Bloomberg.