We open on a hulking, shirtless man reclining on a fold-out chair in a children’s classroom. The chalkboard is marked with annotations. A red and yellow plastic dumptruck sits under a desk, kid’s artwork on the walls. The kids who use the classroom by day are just starting out in life. For Randy ‘The Ram’ Robinson – a big star in the ‘80s, a has-been in the 2000s – it’s almost curtains.

As the popularity of professional wrestling waned, Randy, now in his late fifties, refused to adapt, demonstrating a stubbornness that is all too common – and tragic – in men. It is through his exploration of this that director Darren Aronofsky crafted one of his finest films and his most shocking exploration of broken masculinity to date.

Portrayed by a never-better Mickey Rourke, what little luck Randy had is now a distant memory. He’s living in his van. His jacket is patched together with electrician’s tape. He wears a hearing aid. He’s reliant on painkillers and steroids. In his younger years he failed as a father and now his grown-up daughter wants nothing to do with him. In his free time he recounts old war stories, showing off his old wrestling scars to Marisa Tomei’s exotic dancer, Cassidy.

Randy is a man who had his shot and then froze in time. While his biggest opponent operates a chain of successful garages, Randy is still touring the circuit, wrestling in schools and working men’s clubs for chump change. In the detritus of his career, he feels the only thing he can do is keep going. In the hair-metal days of ‘roided-out dudes with tight pants and platinum hair, Randy was a king, now he’s a warehouse shift worker; when he asks for extra shifts, his boss quips: “They put the price of tights up?”.

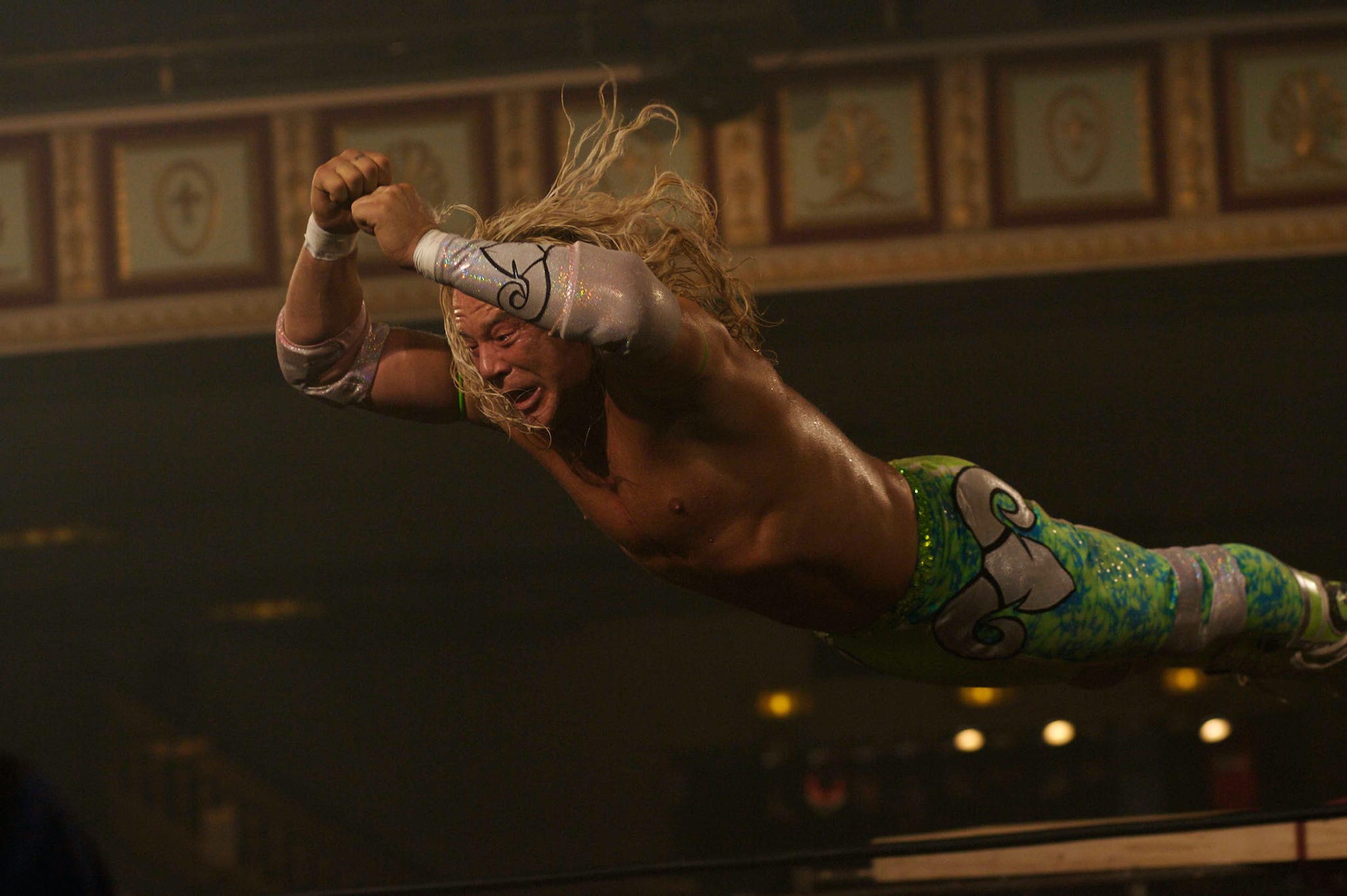

He’s a man play-acting, both in the ring and out of it. Clad in spandex, he pretends he still has the vitality of a man 20 years his junior – even when a man 20 years his junior is spraying him in the eyes with bug spray or attacking him with a nail gun. Randy may battle through, but the pills he requires to do so are slowly killing him.

Out of the ring, Randy’s pretending he can have a shot at happiness – even when his own actions derail him at every turn. In his relationships with his daughter (Evan Rachel Wood) and Cassidy, Randy does have a chance at a normal life, if only his pride would let him take it.

A heart attack seems to put things in perspective. Randy begins a journey of redemption and repair. But, as things again fall apart piece by piece, Randy can’t – or won’t – adapt, reverting back to his factory settings. He signs up for a 20 year anniversary match with his most famous opponent and from that point, the writing is on the wall.

Despite its abrasive (and bloody) subject matter, there is much beauty in The Wrestler. Shot on 16mm film, winter-time New Jersey is suitably melancholy. And, for a film about the most bombastic of sports, Aronofsky tells an incredibly subdued story. Scenes of actual wrestling register as brash intrusions among the many intimate, human moments. For a director known for the OTT likes of Mother! and the druggy heightened reality of Requiem For A Dream, The Wrestler displays perhaps his most restrained direction until this year’s The Whale.

This stillness extends to Rourke, himself no stranger to taking a few blows; between 1991 and 1994 he left Hollywood to embark on a boxing career. Sin City, released a few years earlier in 2005 was touted as his return to the mainstream. The Wrestler was a different beast, with his gentle, determined, and rage-filled performance earning an Academy Award nomination, and a Golden Globe win. There’s more than a touch of Rocky Balboa about Randy, but Rourke skips the cartoonishness of Stallone’s best performance for something altogether more grounded, even if Balboa never frequented a sun bed, or got his roots dyed. Equally as great, Marisa Tomei provides counterbalance with a vulnerable but commanding performance that bagged her another much-deserved Academy Award nomination.

It is this rage that ultimately proves Randy’s undoing. His daughter tells him “You’re a walking fuck up!”, Cassidy doesn’t want to pursue a relationship, his job at the deli counter is too much. Lacking the ability to find other solutions, Randy goes full breakdown, exacting bloody revenge in the supermarket through a stomach-turning act of self-mutilation. After that, he beelines for the ring and his now re-instated 20 year reunion match, despite knowing that setting foot in the ring again will likely kill him.

It’s the same toxic urge that drives men to perform mass acts of violence in real life; the feeling that they have no place in society; “The world doesn’t give a shit about me,” he tells Cassidy, as if it were fact. Disgusted by his outlook, she leaves him to his fate.

The ending of The Wrestler can be viewed as a man choosing to go out on his own terms, even if it means death. In another decade (say, the ‘80s) that might have been the ultimate macho move. Now, as Randy climbs the ropes to end the fight with his signature move ‘The Ram Jam’, all we can do is watch in horror.