In February 1976, at the dawn of punk, 19-year-old Danny Boyle was at university in Bangor, North Wales, studying English and drama. His first inkling that something —something big — was happening elsewhere was a write-up in the NME of a performance by a new band at The Marquee Club in Soho, London, at which a chair was hurled across the room. “Well I didn’t think they sounded that bad on first earful — then I saw it was the singer who’d done the throwing,” wrote the critic Neil Spencer.

The band in question was the Sex Pistols, who would go on to define the look, the sound and the attitude of one of the most important and influential movements in British pop culture. Punk arrived, as Boyle tells it, in the nick of time.

“Britain back then was stultifying, in a way that you cannot imagine,” says Boyle, now 65 and one of Britain’s most popular and successful film directors. “You were young and then you were old, and there was nothing in between. The Pistols said, ‘Fuck that’. They blew that apart. The country genuinely did shake. There was terror about our children pushing safety pins through their nose and spitting at each other, wearing see-through clothes and bondage.”

In 1977, when Boyle and his friends finally got their hands on the band’s one and only album, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols, they “played it to death”. But by the time Boyle made it to London in 1978 — to work in theatre, later becoming deputy director of the prestigious Royal Court — the Sex Pistols had already split up, self-destructing on a tour of America. Punk, at least its first wave, had crashed. But the Sex Pistols’ brief moment of infamy proved to be a turning point for Boyle: in his breakthrough film, 1994’s Shallow Grave, a charmingly depraved story of a flat-share gone wrong, and his electrifying, generation-defining follow-up, 1996’s Trainspotting, the DIY spirit and irreverent ethos of punk are unmistakable.

“I love movies, but it was always music more than anything that drove me,” he says, with the cheerful energy that he is known for and with which his films — even the darkest ones — are often infected. (By way of trademarks, see also: killer soundtracks, which have featured Iggy Pop, Blondie, Sigur Rós, MIA, Nina Simone and, most memorably of all, in Trainspotting and its follow-up T2, the British electronic-music duo Underworld.) Boyle, with his familiar square-framed glasses, high forehead and bushy, quizzical eyebrows, grins as regularly as he takes a breath; or maybe, given that he talks at 100 miles an hour, even more. “I’ve always been much more that person than the auteur film-making kind.”

He is telling me this in the glassy top-floor meeting room of a post-production house on Chancery Lane in central London. It is here that he is grading his new project, Pistol, a six-part series about the formation of the Sex Pistols, adapted from Lonely Boy, the eye-wateringly candid autobiography of the band’s guitarist, Steve Jones. For someone as steeped in punk lore as Boyle, describing it as a “passion project” doesn’t even come close.

The new series, which starts on Disney+ in May and is written by frequent Baz Luhrmann collaborator Craig Pearce, is Boyle’s first major TV project after a career dominated by film-making. It is not, however, his first attempt at a punk-memoir adaptation: he had planned — until she changed her mind — to direct a film version of the 2014 autobiography by Viv Albertine of The Slits, Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys (“the best title of a book ever”). Nevertheless, the Sex Pistols’ short lifespan gives this series a contained structure — and an end point — that the director found appealing; no six-season run for this one. “We didn’t want it to become soapy,” Boyle says. “It’s two years, one album and 12 songs. That’s it.”

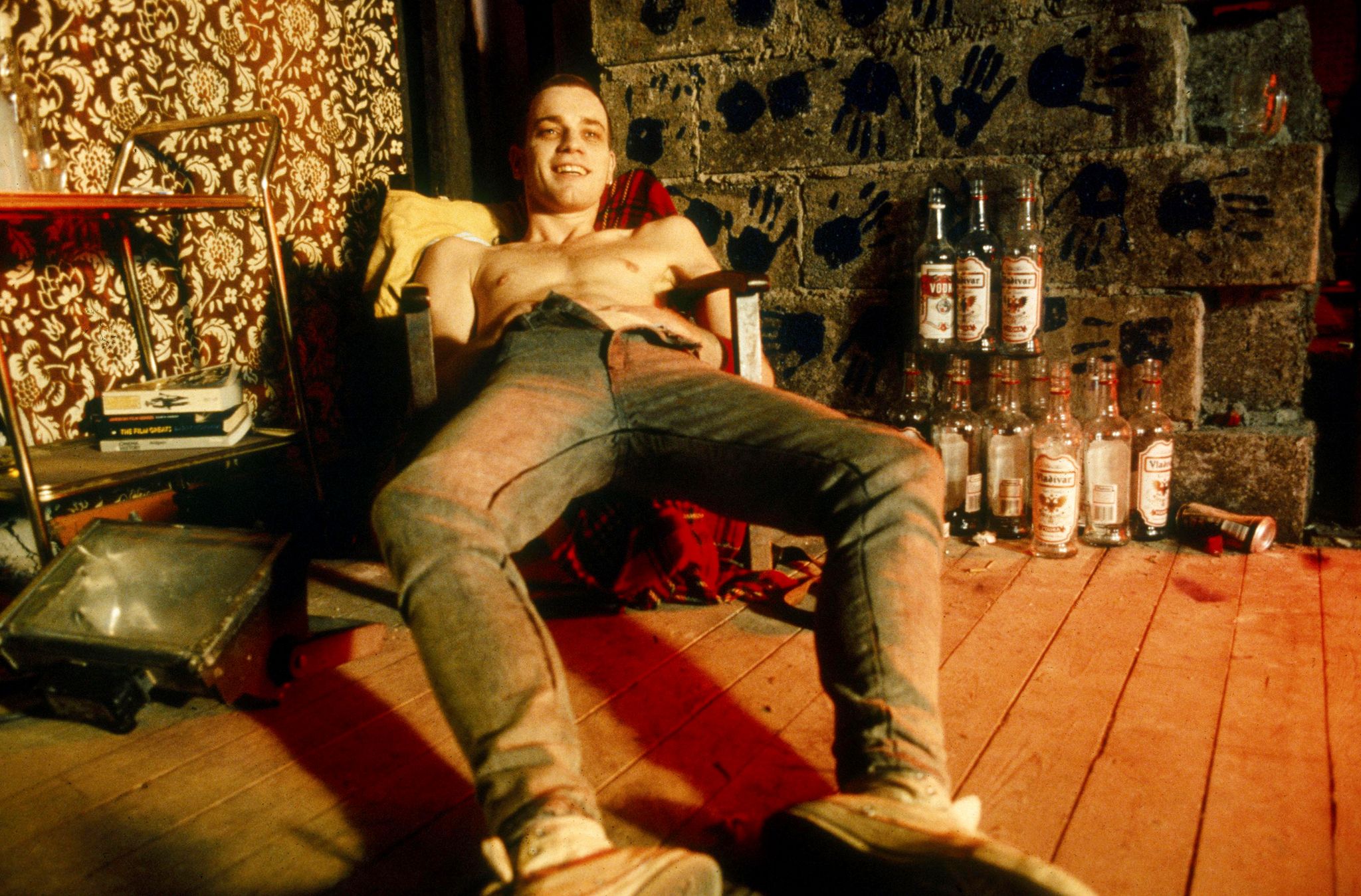

Pistol stars predominantly unknown and first-time actors: Anson Boon as frontman John Lydon, better known as Johnny Rotten; Louis Partridge as Sid Vicious; Christian Lees as Glen Matlock, the bassist sacked to make way for Vicious; Jacob Slater as drummer Paul Cook; and Toby Wallace as Jones. It’s something that has worked well for Boyle in the past: Ewan McGregor in Shallow Grave; a little-known Cillian Murphy in zombie-apocalypse thriller 28 Days Later; Dev Patel making his feature-film debut in the feel-good rags-to-riches drama Slumdog Millionaire. There’s an appeal, says Boyle, to actors who “don’t carry anything yet”.

The show also features portrayals of a smattering of the band’s associates and punk icons, from Chrissie Hynde and Siouxsie Sioux to Pistols Svengali Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood, whose King’s Road boutique, Sex, was responsible for the slashes and the safety pins. Boyle brought in a number of the real figures — including Jones, Cook and Hynde — as advisers, although not everyone, he says, was keen at first. When he initially approached Westwood, now Dame Vivienne, to give some insight into the period, she offered the unimprovable response: “I’m not really interested in the past.”

Lydon, true to form, refused to be involved, to the extent that Cook and Jones had to sue him to get permission to use the Pistols’ music in the series. After losing the case in August last year, Lydon issued a statement in which he expressed fears that the show would “water down and distort the true history of the Sex Pistols”. Boyle seems unfazed. “I met Lydon once, and I like him very much, despite all the court cases. John complains we didn’t approach him. We did approach him, and I would have loved to have him involved, but you’re never going to in a million years.”

Pistol arrives, as its makers surely know, at an interesting moment. The punk summer of 1977 was Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee, soundtracked by the Pistols’ “God save the Queen”. This summer, we celebrate another jubilee. And, just as Britain was mired in political and economic disquiet then, so it is now. “I don’t know if it was directly political,” Boyle says of the show’s auspicious timing. “If I’m being brutally honest, I think it was more to do with my age and ability to get it made. I wanted to do punk because it was the big formative experience for me, and it’s overshadowed everything I’ve done.”

That Danny Boyle should have emerged during the punk era is not surprising given his age and background. He was born in Radcliffe, north of Manchester, in 1956, to Irish Catholic parents — his mother Annie, known as “Babs”, worked as a dinner lady at his school, and his father Frank at Kearsley Power Station — and was one of three children, with a younger sister, Bernadette, and a twin, Marie. He now has three grown-up children of his own with his former partner, Gail Stevens, a casting director, and lives in Mile End, east London.

It is perhaps more surprising given his output, which seems in some ways to espouse the opposite of the punk ethos: to search for warmth and humanity in the bleakest situations. Trainspotting, named by the BFI as the 10th best film of the 20th century, may have a grim premise — a group of heroin addicts in 1980s Edinburgh trying, kind of, to get clean — but it is also a rousing story of adolescent larking-about, young lust and enduring friendship. With Slumdog Millionaire, which won eight awards at the 2009 Oscars, he found light in the dark story of a young Indian boy pinballed from one cruelty to another, choreographing it into a sprawling and optimistic yarn about life and luck. There aren’t many people who could make a fun film about someone sawing his own arm off, or a biopic of a technocrat without making audiences want to do the same, but Boyle could, and indeed did, with 2010’s 127 Hours and 2015’s Steve Jobs respectively.

He is also a wonderful chronicler of Britishness, using the lens of pop culture to tackle big topics of national identity in fun and subversive ways. Take, for example, his most recent film, 2019’s Yesterday, a romantic comedy written by Richard Curtis which imagined a world in which only one person — a struggling musician, no less! — could remember, and capitalise on, the music of the Beatles. This talent has not gone unnoticed outside of the film world. In 2012, Boyle was asked to oversee the opening ceremony of the London Olympics. The spectacle he devised, called Isles of Wonder, put Shakespeare and the Spice Girls proudly side-by-side, and portrayed everything from the “dark satanic mills” of the industrial revolution to NHS hospital beds, magicked into giant trampolines.

Ten years on, with the country reeling from the successive blows of austerity, Brexit, Covid and war in Europe, his jubilant vision of Britain must feel to him, if not unrecognisable, then at least distant. He isn’t swayed. “What we were trying to express,” he says, of the 2012 ceremony, “was something about the nature of our society, which is basically a decent one, with all of its faults. I think that holds, personally.”

As much as his films, the success of the 2012 opening ceremony — which climaxed with the ultimate celebrity coup: Daniel Craig as James Bond appearing to skydive into the stadium with HRH The Queen — cemented Boyle as a beloved figure in British cultural life. That same year, he was featured alongside iconic Brits including Grayson Perry and Kate Moss in a re-imagining of the Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover by its original artist Sir Peter Blake. Whether he liked it or not, “national treasure” status was in the air. But there was still a bit of punk left in him: soon after the Olympics, he was offered a knighthood, which he refused. “I thought it was very insensitive of them to ask me, to be honest,” he says, still tickled. “And I never leaked it — fucking Mark Lawson blurted it out [during a BBC Radio Four interview in 2012]. I remember people saying, ‘Oh, you should accept it on behalf of all the [volunteers who worked on the ceremony]’, and that sort of thing just makes me vomit. It’s literally a way of separating yourself.”

In his film work too, and even quite recently, Boyle has been known to run up against the establishment. In 2018, he signed on to direct the 25th Bond film with his long-standing screenwriting partner John Hodge, reuniting him with Craig for what would be the actor’s final outing as 007. This partnership, though, was to be less successful than the sky-diving-with-The-Queen stunt: No Time To Die — or “The Most Cursed Bond Movie in History”, as it may well be remembered due to the injury Craig sustained while filming and the premiere being pushed back three times — was eventually released last year, long after Boyle and Hodge had stepped away from the project. The rumour was that Boyle walked because he had wanted Bond to die and producer Barbara Broccoli’s Eon Productions wasn’t having it. Anyone who has now seen No Time To Die will know this cannot be true. So, what happened?

“I remember thinking, ‘Should I really get involved in franchises?’ Because they don’t really want something different,” Boyle says.“They want you to freshen it up a bit, but not really challenge it, and we wanted to do something different with it. Weirdly — it would have been very topical now — it was all set in Russia, which is of course where Bond came from, out of the Cold War. It was set in present-day Russia and went back to his origins, and they just lost, what’s the word... they just lost confidence in it.” He pauses to look me in the eye. “It was a shame really.”

Boyle has seen No Time To Die and is in favour of its surprising conclusion, but he does begrudge one thing about how he parted ways with the franchise. “The idea that they used in a different way was the one of [James Bond’s] child, which [Hodge] introduced [and which] was wonderful,” he said. Is there any prospect of him returning for a future Bond instalment? “I don’t think so,” he says with a soft smile. Still, he talks excitedly about the prospect of an actor like Paapa Essiedu (I May Destroy You), whom he had seen in a play at the Old Vic a few nights previously, taking on the role, before attesting, as he has before, that “[Robert] Pattinson would be a great Bond”, should he be willing to trade in the keys to the Batmobile for the DB5.

Perhaps getting caught up in the machine, as he did with Bond, is a mode of working to which Boyle is not fundamentally suited. He has spoken previously about the shock to the system he felt while making the 2000 film The Beach, adapted from Alex Garland’s novel of the same name, and starring a young Leonardo DiCaprio. As a director who had been used to making smaller indie films and getting his hands dirty, with limitless resources at his disposal he suddenly felt like a spare part. “I’m much better under the radar a bit,” he told The New York Times in 2007, “and actually figuring out how to make things work.” (Despite mediocre reviews, the film still made about £111m on a £38m budget.)

Pistol, then — a drama about a group of scrappy adolescents with something to prove, played by a bunch of young actors in a similar position — should be a return to the kind of filmmaking Boyle enjoys (depending, of course, on the relative freedoms or restrictions of shooting it for a mega-studio like Disney). In telling the story of a band who crashed and burned, and of what endured in the popular consciousness after the embers went out, Boyle can once again reflect ideas about what Britain is back at us, for better or for worse: to look into the gutter, but search for the glint.

“I tried to let Pistol have a freedom that was unpredictable,” he says with a chuckle. “But I think there is some truth in the idea that you do always make the same thing again and again and again.” Given the consistency and popularity of his output, you might consider that no bad thing and, after 30 years in the business, Boyle has settled on an approach to his work that is, like the man himself, both cheerful and sanguine: “I’m very optimistic about everything except success.”

If there is one idea that has guided him over the years, he says, it is the importance of looking outwards. It was a principle instilled in him early on in his career, and has served him well. “When I worked at the Royal Court, it had a very arrogant attitude toward the audience,” he says of his time at the London theatre. “It wasn’t part of our job to make it attractive to these people, it was their job to appreciate it and turn up for this glorious piece of art. I’ve tried to do the opposite [since]: I think it is your absolute obligation to work as ruthlessly as you can to make the story you want to tell appealing, and I have that in my bones.”

‘Pistol’ premieres on Disney+ on 31 May