On Friday March 8, 2019, a new show arrived on the Netflix homepage, changing the fortunes of a single sport forever, and giving new meaning to the phrase “car crash TV”.

Formula 1: Drive to Survive promised behind-the-scenes access to the strange and rarefied world of the elite motor sport — where teams are owned by unsavoury petrochemical tycoons and 20 turbo-charged hobbits with unplaceable accents hurtle across the globe in space-age racing cars with million-dollar engines that can hit 230mph.

Formula 1 had been popular for decades without ever being remotely cool. It was the sporting equivalent of a middle-aged potbelly poured into bootcut jeans. Incredibly, Formula 1: Drive to Survive would transform this travelling circus of unimaginable wealth, inflated egos and cutting-edge engineering into something that otherwise politically correct progressives could admit to following. Even Americans, for decades resistant to F1’s high-pitched siren song, professed themselves converts.

How does a sport that ought to offend every contemporary liberal sensibility, celebrating (as it does) sports-washing autocracies, playboy billionaires, toxic fumes and rampant male aggression, thrive in an age when confessing to sipping from a single-use plastic cup risks potential cancellation?

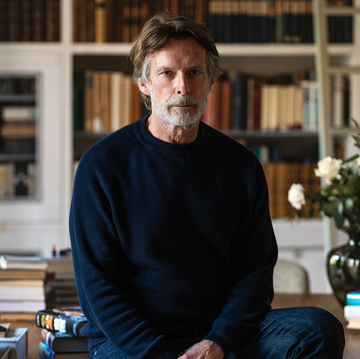

“I don’t think anyone envisaged it landing the way that it has,” Drive to Survive producer James Gay-Rees tells Esquire, on a video call. “You never can. It doesn’t matter what you’re making. Even Tom Cruise lands the odd turkey.”

F1, Gay-Rees says, does have some obvious advantages to the documentary filmmaker (he has previous as the producer of Asif Kapadia’s brilliant Senna, among many other acclaimed films). “At the end of the day,” he says, “it’s young, good-looking fighter-pilot types risking their lives in rocket ships, and you don’t know if they’re going to make it. The Americans, who were maybe discovering the sport for the first time when series one launched, are like, ‘Oh shit, that’s what this is!”

Speaking in 2019, Jean Todt, then the president of the FIA, F1’s governing body, said that international motorsport faced two existential threats: the fallout from a fatal accident and the impact that racing has on the environment. The sport has survived the former tragic circumstance on a number of previous occasions, most famously the death of Ayrton Senna, in 1994. And the element of risk is, of course, a major element of motor racing’s appeal.

But the environmental questions are harder to answer. According to statistics provided by ESPN, of the 256,551tonnes of emissions produced by F1 in 2018, only 0.7 percent was from the actual racing, including all testing, qualifying and races. The logistics — the travelling circus part — made up 45 per cent.

“I think they’ve made massive steps forward,” says James Gay-Rees. “F1 used to be a bunch of cigarette packets driving around a circuit,” he says, referring to the tobacco logos that once predominated. “The fuel is becoming more sustainable, and the sport is populated by some extremely clever engineers. Whether there’s enough time for them to crack it, who knows?”

“They are making attempts to improve,” says Naomi Schiff, a professional driver and an F1 pundit for Sky Sports. “There have been massive changes in the fuels used and a move towards biofuels. They should probably make their calendar more sustainable first, but it’s difficult.”

In any event, partly thanks to Drive to Survive, for many punters, rightly or wrongly, environmental concerns come second to the excitement of the racing, and the human-interest stories supplied by the teams.

Speaking of the Netflix show’s impact on the sport, Schiff says, “Thanks to them I can now talk to my girlfriends about motorsports, and I’ve been racing since I was 11. None of them thought I was that cool before, and now it’s the opposite.

“What Drive to Survive has done is allow the drivers to show off their personalities,” continues Schiff. “It’s much easier to connect with a sport when you feel like you know the people involved in it.”

“It helps that the drivers are quite accessible and modern,” agrees Gay-Rees.

His producing partner, Paul Martin, praises the sport’s embrace of risk, including the decision to allow cameras in. “F1 was the first sport to really open up in that way, and I think they’re reaping the benefits of that.”

During Drive to Survive’s third season, which aired in 2021, the Netflix cameras came uncomfortably close to capturing something that approached Jean Todt’s first existential fear: the death of a driver. At the Bahrain Grand Prix in 2020, the Swiss-French racer Romain Grosjean, driving for the American team Haas, approaches a corner, jostles for space, loses control and swerves across the track and straight into a metal guardrail. We hear a single, clear “Fuck,” as his car, cut into two separate pieces, bursts into flames.

The camera lingers on the back half of the car — a charred wreck of metal and exposed wires. He’s definitely dead, he must be dead. Then, in a scene straight from Hollywood (maybe a Tom Cruise movie), Grosjean emerges from the flames. Somehow, he’s not dead. He spent 28 seconds trapped in an inferno and survived, thanks to the car’s Halo technology, made from grade 5 titanium, which protects drivers from the worst potential debris and destruction. Later on, Grosjean reflects on the moment he made peace with death. “Where am I going to burn first? Is it going to be painful?” he says with a passive expression. It’s heart-stopping stuff, whether you’re a fan or not.

“This is more close to Top Gun than a documentary,” complains the stony Austrian boss of Mercedes, Toto Wolff, in the opening episode of season five. Some drivers, including the Red Bull team’s dead-eyed Dutch maestro, Max Verstappen, the current world champion, have complained about the dramatic element of the docudrama, suggesting that Netflix engineers fictitious rivalries between drivers. For a time he refused to be interviewed for the show.

Verstappen’s boycott is over now, though, in time for season five. Perhaps because, whatever the ethics of the sport or the show, there’s no question it makes for great TV.

'Formula 1: Drive to Survive' season five is on Netflix from Friday