When Netflix announced that there would be a gameshow adaptation of South Korean mega hit Squid Game, the streamer called it a “social experiment”. Studio Lambert, the British production company behind Squid Game: The Challenge, proclaimed the venture “Netflix’s biggest ever social experiment”. Once you start to notice this framing of reality shows, it becomes inescapable. ITV called Big Brother the “ultimate social experiment” when it relaunched the show this autumn. Your smart friend who loves these shows agrees: Yes, they are trashy and lurid, but they also teach us about ourselves.

A social experiment is supposed to test some psychological phenomenon. Here’s a cute one. During the Stanford marshmallow experiment, children could either take one reward instantly (like one marshmallow) or wait 15 minutes and receive a greater reward (like two marshmallows). As phenomena go, delayed gratification is a sweet one, and there’s a less cute Stanford one, with which I am sure you are familiar. Whatever reality shows attempt to uncover about psychology has become increasingly hard to parse. More often, they seem like a nursery for aspiring influencers. Certainly none of them would pass any code of ethics: the obscene cash prizes skew behaviour too much, the tasks are too challenging, both physically and emotionally.

Contestants on Squid Game: The Challenge, plucked from around the world but with a heavy American presence, have swallowed this line of thinking. They speak of strategy and not being there to make friends and make sweeping claims about human behaviour. They talk of karma and alliances and the right way to act. All this builds to a pop psychology façade which seems to say: isn’t it fascinating how people act when there is a lot on the line? I’m not sure you need to put 456 people into a disused RAF hangar in Bedford to prove that, but it must be said, it does make for good television.

A recap for anyone who missed the Squid Game phenomenon. The South Korean drama, created by Hwang Dong-hyuk, followed 456 down-on-their-luck contestants who had to compete in a series of children’s games for a £28 million cash prize. If you lost a game, you were killed. It became Netflix’s most-watched series ever, praised for its originality and commentary on wealth inequality. Spin-offs were inevitable, though news of a reality competition raised eyebrows. In Squid Game: The Challenge, 456 contestants, each with a sob story, compete in a series of children’s games for a $4.56 million cash prize. No one dies, though paint packets, attached to their body, do explode with a satisfying chest thump.

Many, many people have pointed out that creating a gameshow around Squid Game, a blunt and bloody commentary on wealth inequality, misses the point of the original show but that argument misses another point of the show: it’s just good TV. Squid Game: The Challenge is also good TV. Many of the challenges are exactly the same as the show. Red Light, Green Light, based on Grandma’s Footsteps, opens the game. In the second, Dalgona, players have to cut a cookie into a shape with a pin. Those are both tense affairs, even without the threat of death. The paint may be black and not a bloody red – I’d love to know how they established this particular boundary of good taste – but the fear is real: when contestants are eliminated, they fall to the ground, with the conviction of Willem Dafoe in Platoon. What really sings are the tasks between the games, often deployed as the contestants hang about the dormitory. These are creepily effective, delivered by a rotary phone or Jack in the Boxes, and tap into what made the show great: surprise.

All the rest is very swish, as you would expect from Netflix and co-producers, Studio Lambert and The Garden. Clever editing cranks drama to 11, frequently blurring the line between reality show and scripted sci-fi. I found myself admiring the editors rather than enjoying the show. It is, more than anything, a triumph of casting. There’s Italian-Londoner Lorenzo, who “doesn’t believe in the values of the corporate world anymore”, and a heavily-tattooed doctor, and a mother-son duo. They talk about childhood trauma, divorce, wetting their bed. They are frequently struck down for their hubristic comments. And the very best: once players are eliminated, they talk about contestants in the past tense, as though they are chilling in purgatory and not a Heathrow departure lounge.

A lot of people will talk about this show’s cruelty, and creating a gameshow based on series about desperate people being murdered for money is indeed eye-raising. Squid Game: The Challenge turns you into the villains of Squid Game: the lecherous folk who pay extortionate money to watch people die (though a Netflix subscription, however increased, pales in comparison to their fee). But this adaptation becomes more cruel when it moves away from its dystopian inspiration and devolves into every other reality game show, as ruthless contestants form gangs and grudges, revealing a more substantial, uncomfortable truth about this genre: why do we like watching people turn on each other? This show does not have an answer, but you’ll likely binge it anyway.

‘Squid Game: The Challenge’ is available to watch on Netflix

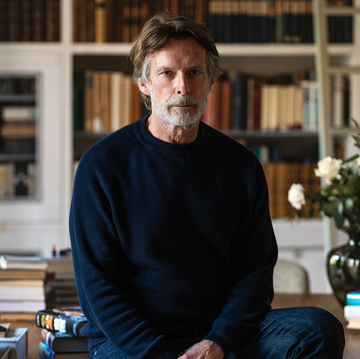

Henry Wong is a senior culture writer at Esquire, working across digital and print. He covers film, television, books, and art for the magazine, and also writes profiles.