And just like that, with the mind-clearing galumph of a disappearing Tetris row, the cultural landscape becomes two shows lighter. Call it daylight saving TV: in time for a summer evenings spent reading under trees (har-har), two endlessly-discussed series cleared out. The first was Succession, which ended its four-season run with a triumphant, pleasingly flat finale. And over in streaming land, Ted Lasso called time on a third – and heavily-rumoured final – season with a less rapturously-received conclusion. The proximity of the finales highlights just how differently these shows, both once white-hot, ended: one with a (purposefully muted) bang, and one with a less intentional whimper.

Succession and Ted Lasso are, of course, different shows. The former is a prestige family drama about a Murdoch-esque media empire, the latter a once-diverting sitcom about an optimistic American football coach (is that tautologous?). But good TV is good TV, and there’s a clear lesson in Succession’s safely-assured legacy and Ted Lasso’s demise.

Succession’s fourth season will not go down as its greatest, though certain episodes (“Connor’s Wedding”, “Church and State”) will lead some to believe that the show is an all-timer. Is that true? Maybe. Time will tell. But it is entirely possible to read the coverage of Succession, which frequently likens show creator Jesse Armstrong to Shakespeare, and feel like releasing a Logan-like howl. It is clearly good, but it is not always that deep. Characters say exactly what they mean; the symbolism is as mysterious as an Excel spreadsheet. The frequent foreshadowing (people now call this “easter eggs”) was not difficult to parse. The careful flourishes, like Kendall’s interrupted elevator ride in the finale, raised this show far above the rest, but that doesn’t automatically make it King Lear’s successor. (And things can be good without being Shakespeare.)

What does set Succession apart from a lot of contemporary television is that throughout the show’s run, the writers never treated its viewers like idiots. There was continuity – an increasingly rare and apparently unnecessary quality in the age of binge-watching – which rewarded close viewing. Nowhere was that clearer than in the final season. To take one example: that scene with Greg’s translation app would not have paid off without the preceding company outing to Norway in which the Roys’ dopey cousin found himself a victim to Swedish bullying.

There was little explanation of business deals, though there was frequent conversation about them: Succession either believed you were nerdy enough to know this already or smart enough to look it up and follow along. When you respect your audience, you can pull off a lot more: killing off your central character in the third episode of the season, or plotting each episode to take place a day after the last. You can thrill your audience, and sometimes frustrate them, because you have earned it.

Ted Lasso veered hard in the opposite direction. While the first season displayed a well-crafted, infectious warmheartedness – I don’t think we can attribute all its success to: pandemic = sad, Ted Lasso = escape – its second outing was a schmaltzy overload. By its third outing, all hope was lost. The show’s writers, which includes leading man Jason Sudeikis and co-stars Brett Goldstein and Brendan Hunt, worked to recapture that early magic, by honing in on some easily-identifiable feelings. “Do you remember when this show used to make you feel good? Or how about empowered? Or tearful?”, they asked, as they set up hasty redemption arcs, love triangles, and storylines which felt like watching an entirely different show altogether.

Any early goodwill, and there was plenty of it, was squandered by the season’s end (it did not help that the episodes bloated to hour-plus extravaganza). And though there’s no official confirmation, Ted Lasso sure felt like a series finale: there was a rendition of “So Long, Farewell” (the show could never be accused of subtlety), an emotional airport scene. Ted returned to the states to be with his son, Henry: a series-long arc which was a believable, if inconsistently compelling, conflict. People got married, people found love. New, slightly dull ventures were set up. Let us pray for peace to accept the eventual spin-off.

Compare that to Succession’s send-off, a finale which felt distinctly un-finale-like. The series-long question – would Kendall take over Waystar? – was answered with minutes to go. The children’s fate confined to those closing scenes: we knew enough about them to fill in the gaps. It didn’t leave you exactly wanting more – four seasons was more than enough time with these characters – but it did leave you feeling satisfied, which, in the current landscape of endless options, is not just a happy ending, but a rare one too.

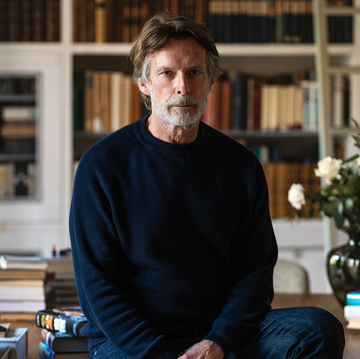

Henry Wong is a senior culture writer at Esquire, working across digital and print. He covers film, television, books, and art for the magazine, and also writes profiles.