“I intend to make pictures with the help of real literary minds,” the media mogul William Randolph Hearst tells the writer Herman J. Mankiewicz on meeting him, according to Mank, the new film that explores the story behind Citizen Kane.

Hearst says he wants to do away with the “gangster flicks and zanies” and instead wants to create movies that are far more true to life. There’s a delicious sense of foreboding in this scene, as we the viewers know that Mankiewicz (known as Mank) will end up mining Hearst’s entire life story - non too favourably, either - for what’s still regarded as one of the greatest films of all time.

The epic Citizen Kane features the downfall of the billionaire media tycoon, Charles Foster Kane, and how his pursuit for power changed the course of his life, told through a series of flashbacks and memories. But it cut too close to the bone for the real-life Hearst, who was said to be furious about this not-even-slightly-subtle big screen depiction, and he engaged in a life-long vendetta against the film, and its creators, Mank and Orson Welles. Well, he did ask for a story rooted in reality... just not this particular one, it seems.

Who was Hearst?

Hearst was born in 1863 into a life of privilege in San Francisco, as his father was a millionaire mine owner. This set him on his path into the upper echelons of the monied elite, as he attended prep school and then studied at Harvard. Two years later in 1887, his dad made him manager of the newspaper he took on as a gambling debt, the San Francisco Examiner. Not bad for a graduation gift at all.

Even from an early age, Hearst had a knack for spotting talent, and signed up writers for the Examiner like Mark Twain and Jack London. But he had his eye on a bigger prize, namely, as many newspapers as he could get his hands on.

“His dream [was] of a nation-spanning, multi-paper news operation,” according to Kenneth Whyte in The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst. So Hearst skipped coasts and headed to New York. Remarkably, at this time, the city had 16 different daily newspapers, and Hearst picked up the New York Morning Journal, going head-to-head with Joseph Pulitzer and his New York World.

We’re well used to the red-top tabloid wars in the UK, but Hearst changed the face of the whole American printing industry in his competitive handling of his titles. Both Hearst’s Journal and the rival World started engaging in price-dropping, while focusing on splashy headlines, sensationalised human interest stories and dramatic crime coverage; otherwise known as the yellow press, an early form of tabloidese. The readership soared and Hearst even managed to poach three editors from the World.

However, the Journal began to fall into ethical hot water around the time of the three month Spanish-American War in Cuba and Puerto Rico in 1898. Setting up the course for well-worn media and political tactics still used today, papers like the Journal stoked anti-Spanish rhetoric and, according to W. Joseph Campbell in Yellow Journalism: Puncturing The Myths, “exaggerated the atrocities to further increase public fervor, and to sell more papers”.

Hearst had begun to realise the powerful synergy there was between media and politics, and he continued adding more publications to his roster, including papers in Boston, Chicago and Los Angeles. By the middle of the 1920s, he owned 28 newspapers, a handful of radio stations and moved into book and magazine publishing, taking over Good Housekeeping, Harper’s Bazaar and, jumping 60 years into the future, a men’s magazine called Esquire. You might have heard of it?

Charles Dance, who plays Hearst in Mank, described his character as “obscenely wealthy” and added: “I suppose the nearest character one could reference now is Rupert Murdoch.”

Politics and Hollywood

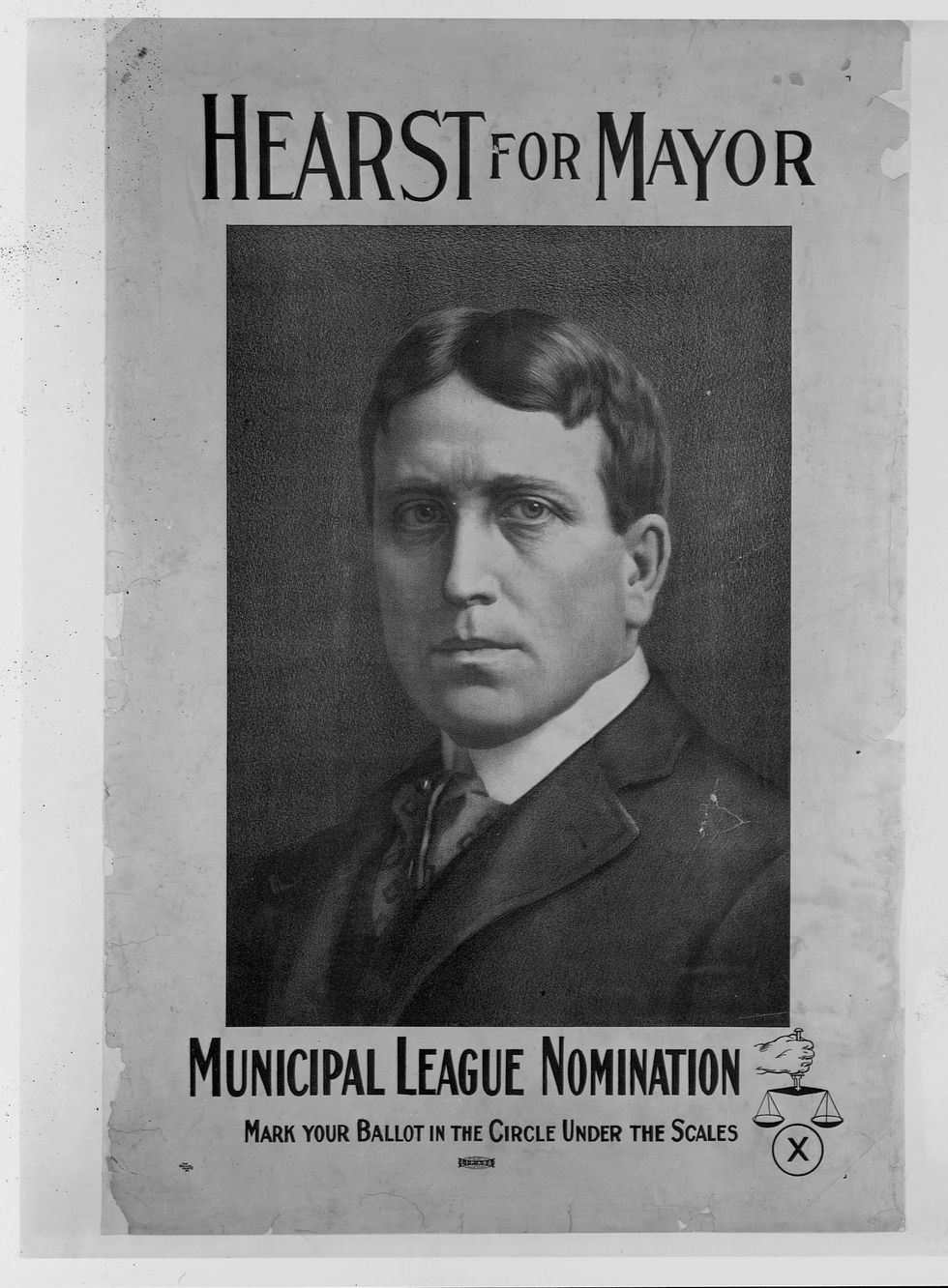

As his media empire grew stronger, Hearst’s political alignment moved from the left to the right, and after once supporting Franklin D. Roosevelt, he turned his alliances elsewhere after The New Deal was announced. Hearst ran for several political positions including Mayor and Governor of New York, but he never took a seat more high profile than Member of the US House of Representatives for four years from 1903.

The Hearst Corporation went through financial struggles, and many of Hearst’s assets had to be liquidated in the ‘30s, but he held on to his publications. He began to spend an increasing amount of time at his San Simeon castle in California, and despite still being married to his wife Millicent Davies, he moved in his long-term lover, Marion Davies (played in Mank by Amanda Siefried).

Being cohorts with MGM boss Louis B. Mayer (played by Arliss Howard) and using his influence to ensure Davies was given bigger roles meant Hearst was now at the centre of another industry: movies, and even better, during Hollywood’s golden age. Despite it being the middle of the Great Depression, it’s estimated 70 million people went to the cinema once or more each week.

Which is why Hearst and Mank eventually crossed paths. Mank was a wise-cracking writer, the toast of the New York literary scene, who was lured to LA to work as head of scenarios at Paramount. Hearst liked to be surrounded by quick-talking “prima donnas, eccentrics, bohemians, drunks, or reprobates so long as they had useful talents", according to Whyte, which is why Mank soon found himself as pride of place at the lavish parties at Hearst’s castle.

In Mank, we see an increasingly inebriated Mank (the stellar Gary Oldman) playing up to the court jester role for these socialites, moguls and Hollywood kingpins, leading Hearst to comment: “Now that’s why I always want Mank around!” But Mank was soaking it all up: the power games at play, the dirty political tricks, while harbouring his own resentments about being continually uncredited in his own prolific writing career in the industry. Commissioned by Orson Welles, he got to work on writing his masterpiece.

The Citizen Kane fall out

When Citizen Kane was released in 1941, gossip columnists Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons are said to have informed Hearst about the uncanny resemblance in the life story of the “fictional” Kane. That the man character was self-absorbed and power hungry was one thing, but he was said to be particularly furious about the character of Susan Alexander, an alcoholic singer who gets the press baron to fund and support her opera career through his newspapers - a terribly thinly-veiled version of Davies. In reality, Davies had actually given Hearst a million dollars of her own money when he went through financial struggles - he even paid tribute to this in his will.

Kane’s ‘Rosebud’ plot device - later revealed to be Kane’s childhood sleigh, signifying his loss of innocence - was said to be Hearst’s favourite flower, and even more gallingly an... intimate pet name for Davies.

Hearst banned all advertising, reviews and mentions of the film in any of his publications, and it’s said he used his substantial powers to try to persuade RKO Films to pull the movie, and asked cinemas not to screen it.

Director of Mank, David Fincher, believes Mank was only ever following the writers edict: write what you know, and it was this that led him to produce his greatest piece of work - even if it was at the cost of a former associate. He told New York Magazine: “I don’t think Mankiewicz could have written as scathing a portrait had he not known who [Hearst] was. I believe that Mankiewicz went into this thing because he needed the money. And when he got there, and he was encouraged by somebody who was not limiting him, but saying, “Go deep, keep going,” he was able to write something he was finally proud of.”

Hearst died, aged 88, in August 1951. The Mayor of Los Angeles asked for the flag at city hall to be lowered to half mast, and told the LA Times: “The people of our city have suffered a great loss. To hundreds of thousands of people in every walk of life, William Randolph Hearst was a great and true friend”.

The ban on Citizen Kane continued after Hearst’s death, but finally, 60 years on after the film was released, his surviving family decided it was time to move on, and the movie was screened at Hearst Castle as part of a film festival. His grandson, Steve Hearst told The Guardian it was “a great opportunity to draw a clear distinction between WR and Orson Welles”.

As the LA Times noted of the news, “rosebuds bloom in the most unlikely of places” - which couldn’t have been quipped better than Mank himself.

Mank is streaming on Netflix now

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts