In these uncertain days, sometimes it’s good to simply sit down. The best place in the world to do so is the Vitra Campus, just inside Germany near the Swiss and French borders. From its tallest building, only five storeys high, it is possible to sit in an Eames lounge chair and see all three countries: the edge of the Black Forest, the tip of Basel and the vineyards of Alsace. It is also possible to see its newest building a few metres away, the Vitra Schaudepot, which since opening in June 2016 has been home to the biggest and most optimistic collection of modern chairs in the world.

Here are all the chairs you love, and can’t afford: Platner, Saarinen, Aalto, Prouvé, Aarnio, Panton, Breuer, Wegner, Dixon, Jacobsen and Newson and back to Frank Lloyd Wright and Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Prototypes, limited editions, designs with impossible systems of weight and balance. If you like chairs, these give life a lift from time to time. Taken as a whole, and viewed as a modern 200-year survey in one place, they also attest to our insatiable creative spirit. No one actually needs another chair, which is a good enough reason to go on making them, and no one makes them better than Vitra.

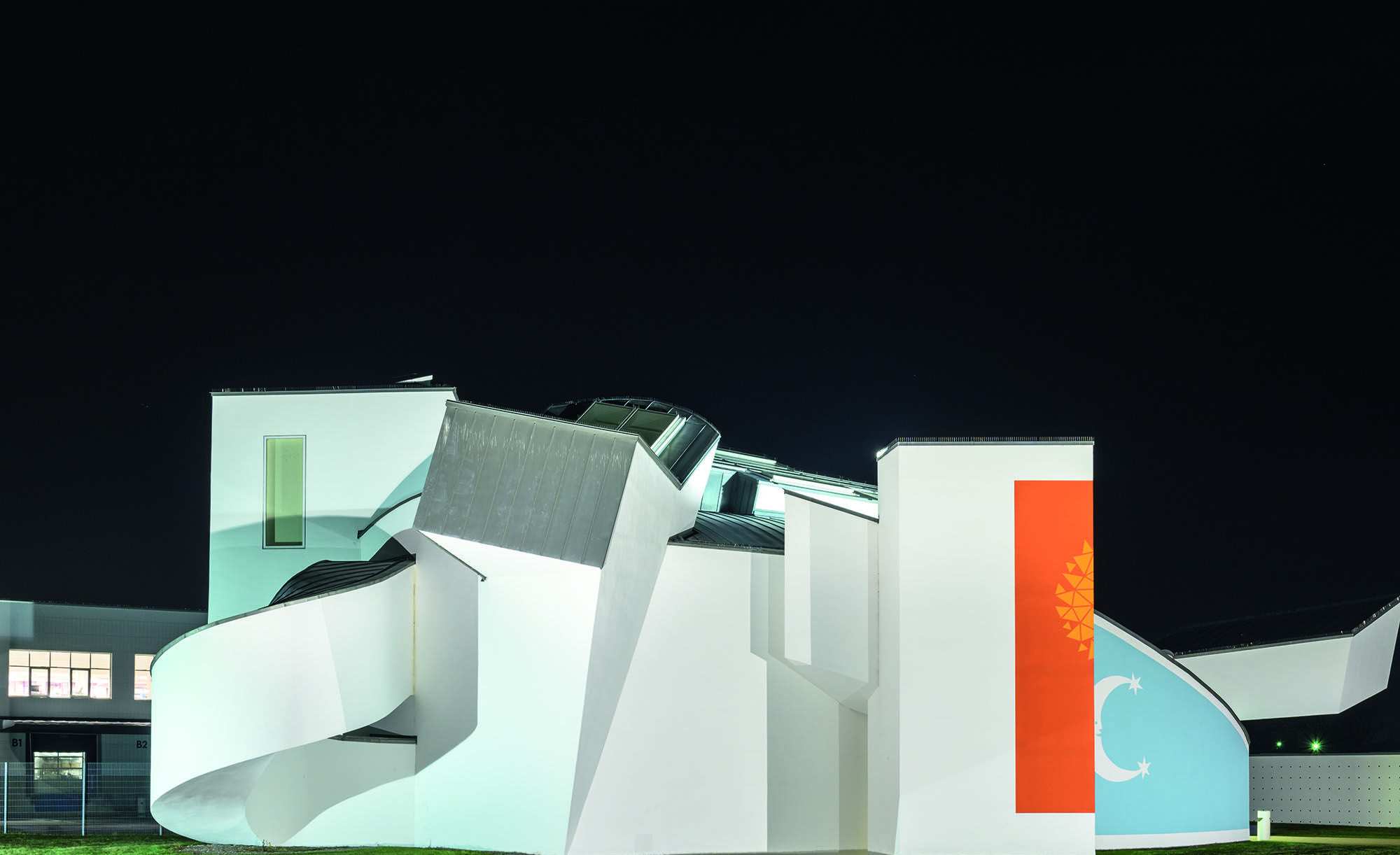

The Vitra Campus is on a flat plot of scrap land with a few cherry trees in Weil am Rhein, a not very pretty city twinned with Bognor Regis. It’s a seemingly remarkable place to erect a small enclave of buildings designed by some of the world’s most daring architects, including Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid and Herzog & de Meuron. We’ll get round to those buildings — some of which are quite crazy — but first let’s look at the chairs, because they are where the Vitra story begins.

In 1953, shopfitter Willi Fehlbaum was on holiday in New York when his taxi passed a shop with an Eames chair in the window. Liking it very much, he struck a deal with the manufacturer Herman Miller to produce the chair in Europe. Where should it be made? On a bit of land covered in cherry blossom in the most southwesterly part of Germany, inherited by his wife Erika. Thus Vitra manufacturing was born and the Fehlbaums became friends with Charles and Ray Eames; and a passion for one chair became a passion for many. Vitra supplied offices and other commercial outlets, and a few products found their way into the sort of homes that tend to appear in magazines.

Then in 1981, just when things were going so well and Vitra had expanded from chairs to all types of furniture, a fire caused by a lightning strike burned down more than half of the production site. The company had to start again, founding the Campus, an attempt to celebrate design in all its far-flung forms, an adult playground where function met expressionism and the most daring and egotistical talents in architecture were allowed to create what few in their right mind would allow them to build elsewhere.

The original plan for the Campus was a uniform high-tech look that would grow as demand dictated. One of the biggest high-tech names in the early Eighties was Englishman Nicholas Grimshaw, who put up his first factory on the site just a few months after the fire, with a second two years later. The buildings are curved corrugated aluminium, functional and elegant. But the plan for uniformity across the site was abandoned when Rolf Fehlbaum, the founders’ son, had his head turned by a new friend.

Frank Gehry had built a reputation as a leading postmodernist before young Fehlbaum asked him to design his first building in Europe. Two buildings in fact: a factory and a museum to display Fehlbaum’s obsession with classic furniture. Opened in 1989, the museum was a white confection of blocks and sweeps that appeared to be in continual motion, a building bursting out of itself. It was a direct precursor to the dynamism of Gehry’s Guggenheim in Bilbao and the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles.

The path was set: every building on the site would have an original look by an ambitious designer. Not all the structures would be new — a few smaller buildings such as the Jean Prouvé petrol station built for a Mobil service area in the Fifties, would be imported and spruced up — but all would add to the creation of cacophonous visual theatre. Visitors may now tour this 25-year experiment and emerge with a feeling of confusion, exhaustion and delight, something like visiting Centre Pompidou, MoMA and Tate Modern in one day.

“A crazy man but brilliant!” is how my site guide describes Richard Buckminster Fuller as we enter the geodesic dome that was once part of a Detroit motor show. Leaving, we glimpse on the Campus perimeter the impeccably clean steel and glass bus stops designed by Jasper Morrison. Then the guide says, “and now of course this…” as we approach the building that made the Vitra Campus famous in 1993, the Fire Station by Zaha Hadid.

It was her first completed building, commissioned to house Vitra’s own fire engines and prevent the sort of calamity that burned everything down in 1981. It soon became clear Hadid was more interested in starting fires than quelling them. Engines were stationed in her building for a while but protection was soon provided by municipal services nearby, leaving space to admire Hadid’s sharp pillared roof, unusual vanishing points and oppressive sense of never forgetting you are in a building designed by a maverick on a computer (and those weren’t really pillars as much as a nod to firefighters’ poles). Locker rooms and showers are still intact, but the rest of the space is now used for exhibitions and receptions; students come from all over the world to pick their jaws up off the hard floor.

There are other concrete/acrylic/brick extravaganzas on the Campus, designed by Tadao Ando, Alvaro Siza and the Japanese firm SANAA, but the most remarkable is the VitraHaus by Herzog & de Meuron (2010). This provides the exit-through-the-gift-shop-and-café scenario, and anyone who steps over its threshold will battle to remain solvent. Here you may buy all the dream-home products from the magazines, your Noguchi coffee tables and paper lamps, your Bertoia wire chairs and your George Nelson desks. It’s four floors of living-room and office plans, and once inside it’s possible to forget that one’s shopping in the most beautiful building on the entire plot. It’s Jenga- gone-Godzilla, a stack of elongated black gabled houses with a great view at the top of all three neighbouring countries and a glass workshop below where they’ll construct an Eames lounge chair and ottoman in materials of your choice.

The tour continues to the office of Mateo Kries, art historian and sociologist, a part of the Campus his whole working life and now co-director of the Vitra Design Museum. When he joined in the mid-Nineties, the site attracted about 60,000 visitors a year, now it’s 350,000. “When I came it was a bit like a UFO that landed in a weird place with nothing to do with the surroundings,” he says. “But now the city of Weil am Rhein has grown to the Campus and the Campus has grown to the city. The Campus is part of the urban fabric, it’s not just a collection of architecture.” (And, of course, his is no regular office; called the Citizen Office, it’s a cosy and useful piece of planning by London-based Turkish designers SevilPeach.)

Kries is responsible for the campus exhibitions and public events, a programme that expands every year and supports the notion that the site is one big display case (if only more production facilities would treat their customers this way by offering not just saleable products but their context as well). “We’re aware that design is a lot more than items for the home,” Kries says. “Obviously it’s about all aspects of society as well.”

On his desk, Kries lays out galleys of the book he hopes will become the fat bible for the history of design: many years in the making with 50 authors, Aalto to Zanuso. But the entry for the Vitra Campus may be instantly out of date. “There are discussions about evolutions,” Kries says. “That may lead to other buildings, but we only build if there is a real use for that building.” As with any institution concerned with its place in the world, there is talk of labs and more educational spaces. Kries, however, has identified at least one more possibility: a boutique hotel. “People are staying longer and longer on the campus, so maybe in a few years they’ll want to stay overnight. We have everything that it takes — the space, the tourists, the furniture.”

In the spirit of fully realised design, our tour ends where it began with what Vitra does best, chairs. Kries has a wall poster showing the Vitra range, impossible to examine without selecting favourites. “I’m asked that question very often and I’m never prepared to answer it,” he says. Today is an exception. “This is outstanding, the Rietveld aluminium [1942], folded out of aluminium sheets, so ahead of its time. And the Marcel Wanders Knotted Chair [1996], made of carbon fibre and aramid, coated in epoxy resin and dried as you dry clothes, so you get a chair constructed by the hanging textile.” And perhaps a famous and popular one? “I’d pick the start of Eames furniture, the high-backed Organic Chair [1940] they did for a competition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Made in wood but covered in textile because the moulding did not work successfully. There is a direct evolution you can trace from that first chair to so much of what came later.”

The poster images of the Vitra chairs are tiny but instantly recognisable. To help finance the museum, which is partially independent from the manufacturing arm, the idea arose to make chairs in miniature to appeal to collectors. As Kries points out, “We would not be doing it with a crap merchandise product but with a serious didactic object where you can learn something about things.”

There are about 60 to collect, but learning something about things comes at a price. At 1:6 scale, technical details are harder to master than in full scale, not least because all the materials in the mini pieces, the screws, the leather, the fibreglass, are the same as those in the real ones but thinner, lighter, tinier. A miniature Van der Rohe Barcelona chair costs about £300 and a scaled down Marc Newson aluminium Lockheed Lounge chaise will be around £800 (although, considering an original sold in 2015 for almost £2.5m, this is clearly a steal).

Soon there will be new miniatures to take home after a day at the Campus, quite probably chairs you’ve never heard of, possibly chairs yet to be designed. And these may be exhibited in a building yet to be imagined. Everyone who meets in this strange and wonderful place is keen to view it as an imaginarium. Coming soon will be 3D printed chairs, but soon they, too, will be just chairs in a museum, replaced on design’s cutting edge by other future classics. It’s good that we recognise the worth of chairs and the value of their evolution. “Design should talk to you every day,” Kries says, “and it should take you to places you’ve never been.” Ends