Minimalism

By Michael Collins

I was unaware of it at the time but I opted for “voluntary simplicity” — as championed by the social philosopher Richard Gregg in the Thirties — as a teenager in a Seventies home stacked with stuff. This included ephemeral gadgets (“as advertised on TV”) and furniture passed down through generations and harboured by parents with a post-war, make-and-mend mentality (“it’s good enough for us”). There were the keepsakes bought on seaside Beanos and the talismans believed to bring luck: a horseshoe, a shillelagh. It wasn’t simply that the stuff was overwhelming but that it related to the past.

In a bleak season of platform shoes and power cuts — heels were higher than hopes — some of us were preoccupied by the future. At least those of us who believed the future would be minimalist. The clues were there in the designs of Dieter Rams, the award-winning interiors from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: a Space Odyssey, and its poor relations, those clunky television series that convinced us the 21st century would be metallic wigs and foil tabards. That was tomorrow, in those days.

Nearby, the promise of the future belonged to a failed vision from the past, evident in the sprawling brutalist estates that were a blot on the landscape of south London. European modernism was the impulse behind these doomed monoliths. Concepts that flourished during a decade when Gregg was evangelical about voluntary simplicity, and when the foreign fun boy three — architects Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius and Adolf Loos — were arguing that less is more. Back then, minimalism was intended for the masses, a means of creating functional, uniform abodes that were machines for living. As Tom Wolfe once wrote: “Worker Housing would be liberated from all wallpaper, ‘drapes’, Wilton rugs with flowers on them, lamps with fringed shades and bases that looked like vases or Greek columns. It would be cleansed of all doilies, knick-knacks, mantelpieces, headboards and radiator covers.” But as soon as they had the opportunity, the workers opted for stuff, as surely as they later plumped for home ownership in the suburbs. Eagerly they customised their houses. Some shelled out for a horseshoe and a shillelagh.

Unlike Gregg’s voluntary simplicity, my minimalism had little to do with sustainability and anti-materialism. It was a method of creating a clearing in the chaos. Taking control and keeping order. Perhaps even a way of dealing with loss: what you don’t have you don’t always miss. Maybe such stoicism would make it easier when it came to losing the big things in life — hair, family, faculties. With age the minimalism has become refined. It’s a stance akin to Major Scobie in Graham Greene’s The Heart of the Matter. Whereas other men built up a home by accumulation, Scobie built his “by a process of reduction”. Didn’t the Pet Shop Boys put it best in the track “Minimal”, when they sang of a cell without a criminal?

I have even less than Greene’s protagonist: one plate, one cup, one bowl, one pot. A single bed. A desk. Two chairs and, like Le Corbusier and Steve Jobs, no sofa. But this is not solely about asceticism — aestheticism is paramount. I adhere to the Rams belief that only well-executed objects can be beautiful. The crockery is good white bone china. The desk as slick and Finnish as any in the offices of the fictional ad men at Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce on Madison Avenue’s Gold Coast. “Buy once, buy well” has become more of a mantra than a motto.

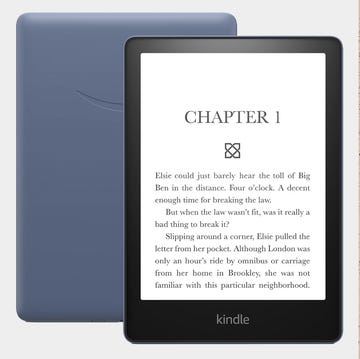

But back to the future. It arrived. It was almost everything that George Jetson promised. It was stark white rooms, it was instruments on our wrists and within our hands that allowed us to dispense with the possessions accrued in adolescence and carted into adulthood: records, tapes, paperbacks, CDs, videos, DVDs. We no longer even needed a television, a lifestyle staple as synonymous with the modern home as the sofa. Ultimately, the future came by way of Apple in simplistic, exquisitely designed gadgets that owed a debt to Dieter Rams. The company’s co-founder — Steve Jobs again — lived a sofa-free adult life and spent every day in a black Issey Miyake polo neck.

Minimalism is the religion of tech billionaires. Sartorially, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg embraces the faith (the Groundhog Day-grey T-shirt) to liberate himself from too many decisions. Twitter is a paean to minimalism, in which the complexities of the world are reduced to a hashtag and limited characters.According to its co-founder Jack Dorsey, restraint inspires creation. This is axiomatic to the minimalists among us. As is the Nineties credo of architect John Pawson: “The minimum could be defined as the perfection that an artefact achieves when it is no longer possible to improve on it by subtraction.”

Where the billionaires went, others have followed. Each one a Henry David Thoreau of the modern age, documenting their experiences in TED Talks and websites such as LifeEdited. Some are attempting to return themselves and their iPads to an idyllic, prelapsarian past that is as mythical as the futuristic utopia those European modernists were banking on. I guess we’re talking Walden Pond with Wi-Fi. The wired cabin has taken over the compact city studio as the home of choice for the 21st-century tech-savvy minimalist. The co-founder of video-sharing website Vimeo, Zach Klein, published a book that pays tribute to this trend, entitled Cabin Porn. The Minimalists themselves, Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus, the duo behind the eponymous website, book and documentary, briefly existed in a cabin in the woods, having jettisoned big homes, big incomes and big stuff. “We want to live a more deliberate, meaningful life,” they announced. It’s a line that chimes with Adolf Loos, who believed freedom from ornament was a sign of spiritual strength.

Somehow this recent trend smacks of the “extravagant austerity” that the Puritans were once accused of. The term “luxury” is now being redefined to return it to something associated with scarcity, elitism and wealth in an era of cheap, bulk buying. Cynics argue that possessions have become a symbol of poverty and minimalism is the preserve of a rich elite. Yet some of us simply missed out the middle man. We didn’t become billionaires and our minimalism was there from the off in that desperate bid to plough a furrow in the chaos that surrounded us.

We’ve always had the luxury the tech billionaires and their fellow travellers now desire. In a word, nothing.

Maximalism

By Michael Bracewell

Style, to paraphrase that great chronicler of individualism and its responsibilities, Quentin Crisp, is knowing what you are and doing it like mad. And that is the creed of maximalism in essence: doing it like mad — layering your look to within an inch of its life.

There are some magnificent historical precedents for successful maximalism — the Byzantine Empire, the Rococo, the castles of “Mad” King Ludwig II of Bavaria — and while to speak in praise of it can resemble lavishing exaggerated but ironical praise onto the worst excesses of kitsch, the cult of style overload, at its best, can take us to a strange but heady place between camp and cool.

From goths to Teds to New Romantics to Instagram fashionistas, those living to the dictates of any particular style code will tell you that it is incredibly hard work and tends to be wound on a mainspring of high-tensile irony. Minimalists, for example, are often grey with fatigue from the stress, expense and near religious commitment required to live in a more or less empty room.

It was the artists Gilbert & George who recalled how, during the late Sixties and early Seventies, when artistic minimalism reached its height, they were always intrigued to see long-haired European artists getting wildly drunk, eating enormous meals and telling the filthiest jokes, only to get up in the morning, go to their studios and reverentially draw

a faint single straight line on a huge sheet of paper.

As the alternative to minimalism — less enshrined, as it lacks the cultural ballast of having started out as an art movement — maximalism is a cult of monumental stylistic excess that these days one might associate with both the phenomenon of the “seven-star” hotel and a pair of Gucci Princetown horsebit tiger mules. (Even the name sounds gold-plated.) In an interesting reverse of minimalism, maximalism is an interior-design lifestyle that seems to have become an art movement, as the swelling ranks of the global super-rich demand evermore expensive, conspicuous and spectacular artworks to fill the draughty open spaces of their many enormous homes.

Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, the patron saints of contemporary maximalism, have catered to this market with a mix of wit, style and devilish conceptual brilliance (each super-sized Tweety Pie or barnacled sea-monster is in one sense a portrait of its buyer); and their games with scale and value have not only maintained the more historic relationship between maximalism and aesthetic gigantism, but offered a moral commentary upon

it.

More traditionally, if the irony of minimalism lies in the cost and personal discipline required to maintain its luxurious asceticism, then the irony of maximalism resides in the claxon-loud significance of its smallest details. The great Tom Wolfe nails the point in his epic novel The Bonfire of the Vanities. A wealthy couple who own a vast apartment in a “good building” on Fifth Avenue are giving a dinner party, and the decor, in Wolfe’s words, “would have made the Sun King blink”. The living room, for example: “was enormous, but it appeared to be… stuffed… with sofas, cushions, fat chairs and hassocks, all of them braided, tasselled, banded, bordered and... stuffed... Even the walls; the walls were covered with stripes of red, purple and rose... a few table lamps with rosy shades provided all the light, so the terrain of this gloriously stuffed little planet was thrown into deep shadows and mellow highlights...”

This is pure maximalism, with its creed not of “less is more” but “more is more”. It is a style choice bel-oved of a certain type of entertainer, financier and (as Peter York anatomised so well in his book Dictators’ Homes) murderous, skull-collecting despot.

In this a pattern begins to emerge. Maximalism at its most overt tends usually to be an insecure commoner’s shot at imperialism: an inferiority complex or one-shot social climb writ large in the language of soft furnishings and gold bathroom fittings; the desire to live in a palatial style that asserts wealth, power, privilege and above all the lordly gratification of whim. And to achieve this, the would-be maximalist must layer the elements of excess until they are rendered not simply epic but surreal…

In its sedimentary form, maximalism had long been the creed of more corporate luxury hotels, in which generic Empire-style furnishings jostled with over-elaborate shoe-cleaning services. Since the mid-Nineties, however, this old-school Rocco Forte Rococo has been challenged by hipster maximalism: all reclaimed warehouse, folksy jelly-bean dispensers, pool tables, unread old books, mismatched furniture, quirky bad art and fake distressed domestic antiques, through which one finds one’s way to the non-gender specific bathroom solely by the light of 30 ecclesiastically scented candles.

True maximalism requires skill to achieve, as much as millions in any strong currency. The 18th-century poet Alexander Pope, who knew a thing or two about the eloquence of details, described the unchecked directives of maximalism in one of his Moral Essays, “Of the Use of Riches”. Right off the bat, a millionaire’s extravagant new villa is written off with the line: “Lo, what huge heaps of littleness around…” In other words, nothing more than a kind of grotesque bigness. In the hands of a true maximalist, however, sheer extravagance becomes a sensibility and a creative medium simultaneously. Ludwig of Bavaria, for example, not only commanded a Wagnerian grotto to be built in one of his castles, but also a golden swan boat in which he might be rowed around its illuminated underground lake.

And why not? The Pop Age reprise of maximalism — from Graceland to Neverland to Alessandro Michele’s made-for-Instagram, Renaissance-inflected designs for Gucci — offers a refreshingly flamboyant alternative to ubiquitous “urban contemporary” (the style equivalent of brushed metal and pale wood), ageing street-style moodiness and stadium rockers who look like cycle couriers.

In simple terms, maximalism, for all its pomp and absurdity, asks us not to take life too seriously. Mesmeric film exists of the legendary concert pianist Liberace giving us a guided tour of his California home, which resembles an enormous luxury department store. He then arrives on stage in a Rolls-Royce, wearing a virgin white fox-fur cloak the length of a squash court. “Takes one to know one!” he quips, roguishly, before flashing his many diamond rings at the fans in the front row and adding, “That’s what you get if you practise!” But he is also roaring with laughter at himself — which makes the whole thing work.