Most of the time the past is not something I remember,” says Thierry Stern, the president of Patek Philippe. “I’m more for the present and the future.” But he does remember one thing clearly from 40 years ago, when he was six. “I was sitting with my dad in his office, and there were four drawers, black wood with red velour inside, and there were six beautiful enamel pocket watches inside. I looked at the watches, and I was not caught by the movement, but by the beauty of the case and the enamelling. That’s when I said, ‘I would like to do that.’ I never stopped telling him. I never stopped thinking about that.”

And so it was, at the beginning of the Seventies, that Thierry Stern’s father reasoned that he never actually owned Patek Philippe, he was merely looking after it for the family’s fourth generation. But with inheritance comes responsibility: what about the next generation? How do Thierry Stern’s own sons — two boys in their mid-teens — react to the possibility of making the company’s adverts come true again?

“We will not push them,” their father says. “We have some clients whose children know much more about Patek than my own. They know the reference numbers and everything. Mine, they should just know about the behaviour, the value and DNA of Patek. The rest I don’t like to push them, because the more you push them the less they will come.”

It is a Thursday afternoon at the beginning of summer, and Patek’s HQ in Geneva has a last-days-of-school feel to it, lots of smiles and bonhomie in the canteen at lunch, endless “bonjours!” in the corridors by the milling machines. The company’s president is in a meeting room decorated with covers of the Patek magazine and a framed pair of signed ballet shoes, a gift from the Bolshoi for past sponsorship.

“The pressure that the kids can feel,” Stern continues. “I’ve seen that for myself. One day not so long ago we were eating, and I don’t know how it came up, but they were discussing who was going to take over Patek in the future. The small one said, ‘It can’t be me because I’m the youngest one…’ and the other one was like this [he makes a quizzical expression]. I could see in his face something was wrong. So we stopped the conversation and I said, ‘Let me explain something. It is not because you are smaller or older that you are going to take over Patek. The one who is willing to and the one who is able to will take over.’ That for me is quite logical. And I told them that I made the choice because that is my life. ‘It is not yours, you’re not here because mum and I have been looking for a child to take over. If you are not willing to, I won’t say I hate you or I won’t be disappointed because of that.’”

Stern says the table talk made a huge difference to his children’s general demeanour, as if a weight had been lifted from their shoulders. “Even the day after they were much more [he raises his hands to indicate a sense of freedom], and suddenly the school grades were also going higher. I could see the pressure was already there at such an age.” Their father had detected a similar pressure on his travels. “I have seen that too often, especially in Asia where you look at the children, and the mentality is that they have to take over. And very often they are not happy and won’t be successful. They will destroy their own lives and maybe also destroy the company.”

On this happy note it may be worth recording that Patek Philippe is thriving. It remains fiercely proud of its position as the oldest family-run watchmaker in Geneva, and appears to be weathering the twin storms of a general downturn in the Swiss watch industry and the shiny competition from a computer company from Cupertino. Its headquarters in the Geneva suburb of Plan-les-Ouates is expanding, and the case manufacturing, polishing and stone-setting wings at Perly and La Chaux-de-Fonds will soon occupy a new building on-site. The creative expansion of its watch collection scales new peaks and at the 2016 Baselworld trade fair it rolled out another marvellous array for the connoisseur, including, most notably, the ludicrously elaborate and preposterously costly Grandmaster Chime Ref 6300 in hand-guilloched white gold. This costs in the region of £1.7m, which is something of a bargain compared to the Grandmaster Chime Ref 5175 that marked the company’s 175th anniversary in 2014 and was issued in an edition of seven at a cost of £300,000 more.

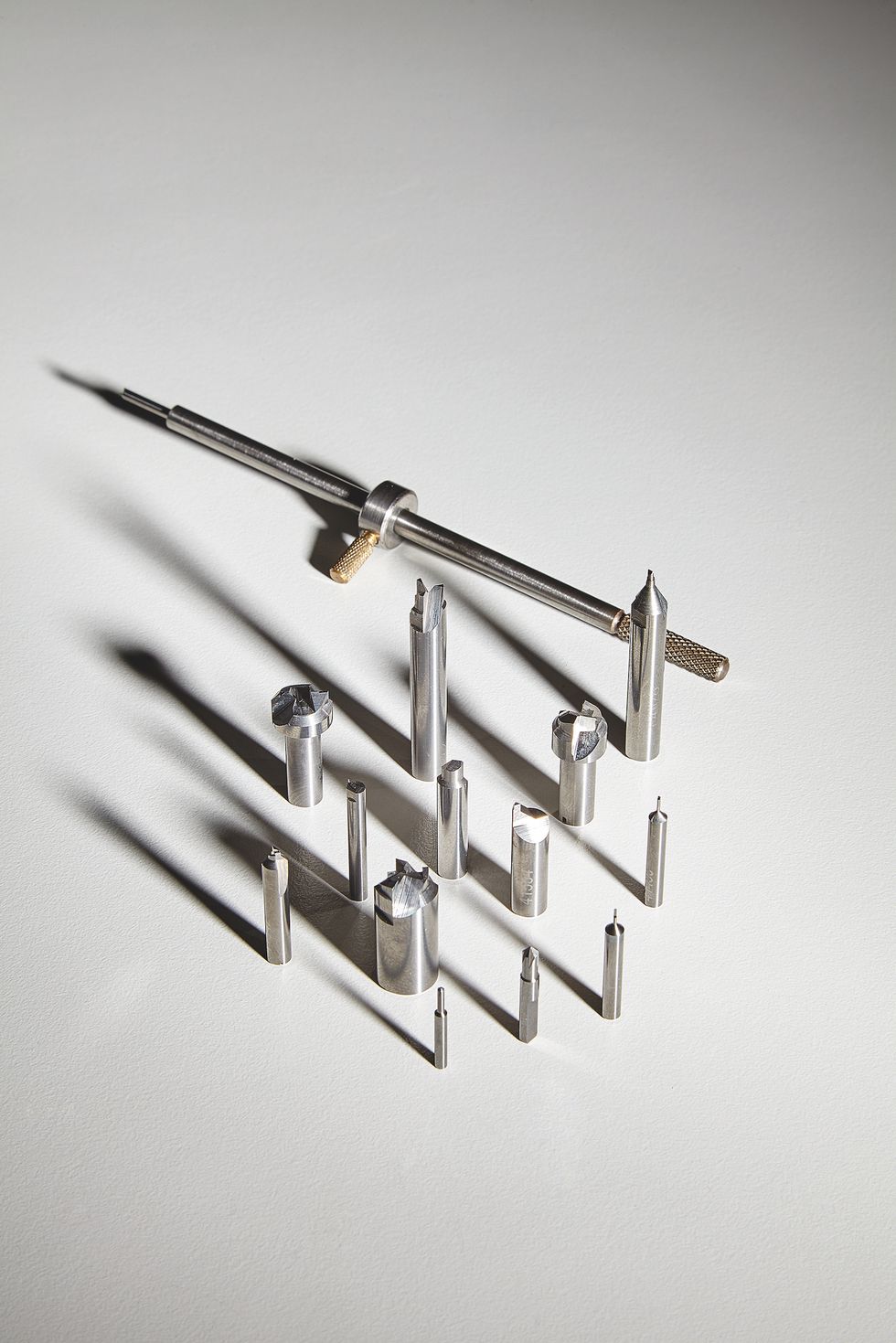

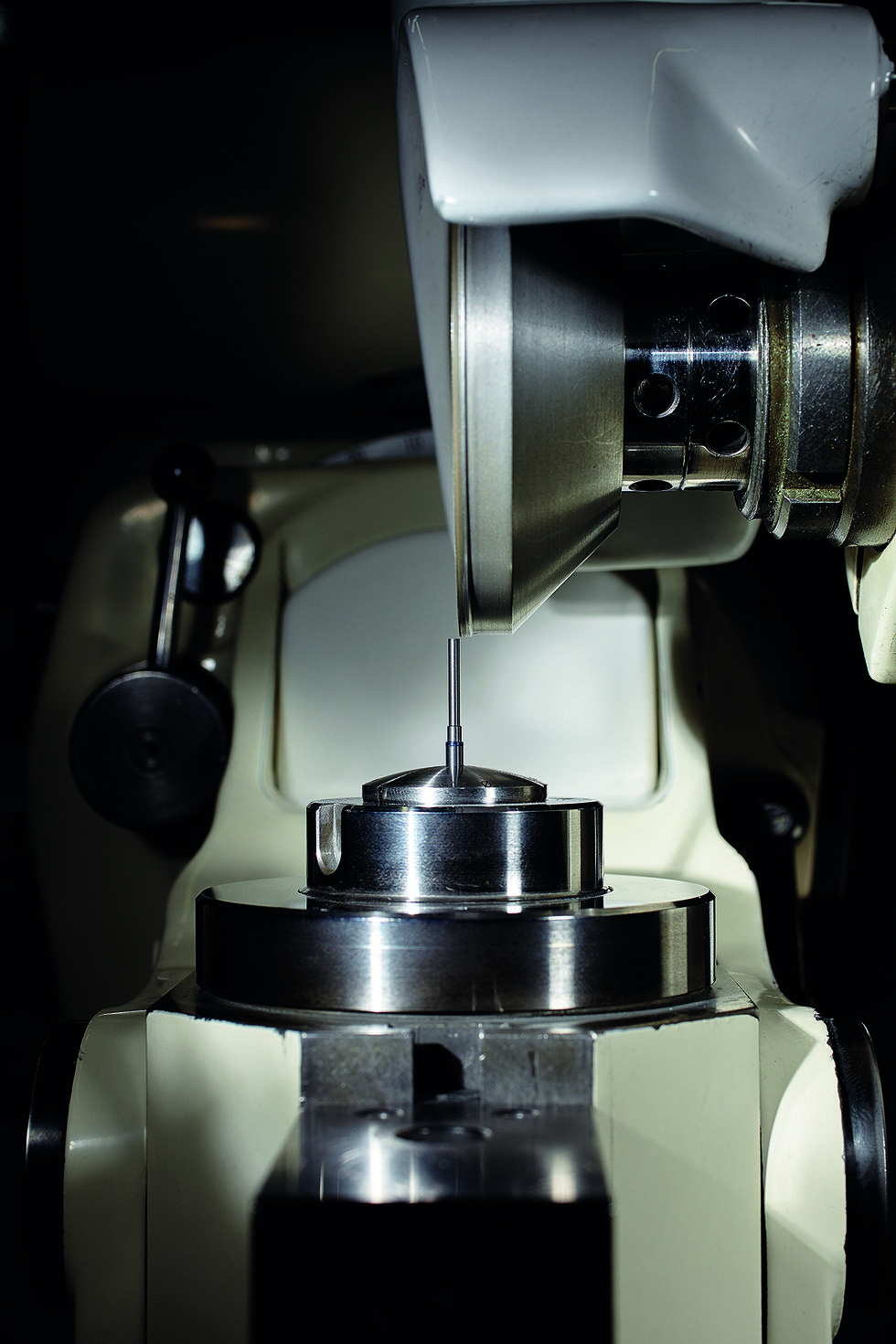

A visitor to Patek’s workshops will have little trouble appreciating why even some of its everyday watches cost the price of a small house, and their servicing the price of a holiday. A glimpse of the tools involved may be enough: upwards of 100 instruments at each work desk — not one eye-glass but four, not three tweezers but 12, not 10 screwdrivers but 30. To the side of the desks are cabinets and carousels with pliers, wands, callipers, blades, hammers, files, saws and brushes, and beyond these a stash of ancient dense boxwood wheels for polishing dials and cases. Beyond the workshops lie huge humming banks of automated milling, punching and grinding machines and conveyor belts priming base plates for the arrival of artificial rubies and impossible complications. But the most notable thing about the Patek factory is how still it is, and how certain it seems of its place in the grand scheme of things. In the few hours I spend touring the creative areas, there is no hint of a frenzied external world, and certainly no intrusion from phones or the internet. Some 200 watchmakers, with decades of experience in every speciality, measure out their expertise in patience and precision, brain surgery and rocket science combined. It’s a place engaged both with deep time and timelessness, a vast airtight container that may as well have been hanging in space.

A visitor hoping that a tour may culminate in a free gift will not leave empty-handed. They will leave white-handed, taking home the branded cotton gloves favoured by dowagers and snooker referees, a prerequisite for handling, at the culmination of the trip, that landmark Patek Grandmaster Chime with its 1,366 parts within a 16.1mm-thick case. How does it feel holding a £2m watch? Delightful! Expensive! Slightly reckless! This dual-faced timepiece with its 25,200 semi-oscillations per hour and its perpetual calendar, strikework isolator display, moon phase, and its Grande and Petite Sonnerie (internal chimes and alarms with tiny hammers striking polished gongs), is as heavy as any wrist will bear. It is, without question, a masterpiece of mechanical engineering, albeit one coupled with a rare example of Patek bling; most of its watches are elegantly understated, which is not a description that fits comfortably here. But the thing I like most about the Grandmaster Chime is the fact that it is neither quartz nor automatic. After nine years on the drawing board, and as many at the workbench, the damn beautiful thing still has to be wound be you.

And this watch, along with all the other wonders that emerge from this air-controlled part of Geneva — all of Patek’s Nautilus, Aquanaut, Golden Ellipse, Twenty~4, Gondolo, Calatrava, Minute Repeater, Perpetual Calendar and Repeater Split-Seconds models — beg the standard but perplexing question: why do we covet them and why would we buy them? And why, given that the atomic time signals delivered to our phones will always provide a more accurate reading than anything mechanical, are we prepared to pay so much money for these tiny glittery effects? (And, then there’s the equally elephantine question: how many owners of the miniature miracle that is the Patek Multi-Scale Chronograph 5975 actually use the tachymeter, telemeter or pulsimeter for anything other than displays of ostentationmeter?)

The president of Patek has gainfully fielded these questions before. “We should never forget that it’s nearly the only jewellery we can have as a man,” Stern says. “And it’s something nice! We should never forget that. It’s not only a watch, it’s a piece of art. If they [our customers] want to keep it as something of value, fine. I would prefer to see them wearing it, but that’s what happens. It’s also a reward I think. Yes, you could give a quartz or digital watch to your son for his wedding, but I do not think those types of items today will last. They will change every year, like phones, so should I engrave a [smart]watch like this and say, ‘Happy Birthday from your dad’, and then what are you going to do the next year?”

Stern remembers a meeting he had recently in New York, “a big table with all the Silicon Valley people”, and he noticed how many of them wore Patek. “I said, ‘Why are you all wearing a watch?’ and they all said the same: ‘It brings us down to earth, and it’s nice to have something mechanical when you’re working in the digital world.’”

Stern has been president of his family’s firm since 2009, although his involvement as a watchmaker stretches back two decades before that. When he took over, production stood at about 40,000 watches a year, and the company now makes about 60,000, still a minuscule output compared to an estimated annual Rolex production of more than 700,000. Stern continues to produce new designs with his wife, and he suggests he may be happier in the workshop than the boardroom. “You can always find new complications. When I started, we had someone very important at Patek, perhaps my dad’s right-hand man, and he trained me regarding business and watches. When he left I was surprised because he told me, ‘Thierry, everything has been done. You won’t be able to create something new any more.’” This was the early Nineties, when Patek was experiencing something of a creative lull. “That touched me so deeply,” Stern remembers, “and I was so angry about that I promised myself it would never happen. The fire was lit when he told me that.”

When we meet, Stern has just signed off the collection for 2028, and he is now working on 2029. We talk about the fine line between growth and exclusivity, and how the watch connoisseur would not take kindly to seeing their investment on sale in the mall. (Patek recently focused its attention on the luxe expansion of its New Bond Street and Paris shops, to the extent that calling them “shops” or even “boutiques” seems obsolete; ateliers comes closer, but with all that alabaster and sycamore in the consulting rooms they’re nothing less than salons.)

For, of course, Patek is more than a watchmaker. It is a kingmaker. In our ardently consumerist climate, status and prestige are the most desirable assets a brand may possess. Exclusivity doesn’t quite capture it: Breguet, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Vacheron Constantin and Audemars Piguet are all coveted brands, but a Patek Philippe places its owner securely at the top of a pyramid. Only Patek and Audemars Piguet have resisted the poisoned charms of the conglomerate takeover (most major watch brands find themselves either within the Swatch or Richemont groups). Stern says he used to get takeover offers regularly, but suitors seem to have got the message now: “Every year before Basel, we get one or two phone calls, a lawyer sometimes. And we say no. I used to say, ‘You can even propose me two billion’ or something, and now I have to raise it a little bit.”

A sale, he believes, “would be a catastrophe for Patek” and probably for its purchasers. “They would be buying an empty shell. All the key people, I don’t think they would stay. If you’re (part of a) group, when you get a new CEO they are changing the strategy. With Patek, the staff know they have the vision and the budget to do it, and they have a chance to build something unique and they can go on until the end. My staff don’t really need a direction today, because they all know their job exactly. I’m perhaps the only one who is useless.”

Hardly true, of course, as Stern concedes later. “As it’s my own company I have to maintain the right level of everything. We need watches that can be worn by a younger generation, and also by the older generation as an everyday watch. We could not survive otherwise — if we only sold [rare and dear] chronos or sonnerie, I don’t think it would work. We have targets in terms of complications, targets for normal movements, for men and women, and also targets in terms of material. We’re not willing to have that many steel watches. The trend today is steel because it’s easier and cheaper, but we should not go above our percentage target. We’ve seen many brands who came from gold to steel and tried to go back to gold, and it doesn’t work.” Of Patek’s popular steel Nautilus models, Stern says, “Of course, I could create 10 times what I’m selling today, but it would be too dangerous, I would become a mono-product. If Patek was part of a group it would be the opposite — it would be 90 per cent Nautilus and [a message that] we don’t care about the future… but it’s not only about money.”

It is also, and this holds true more than for any of Patek’s competitors, about branding, and in particular about the enduring advertising campaign. It was there on the back cover of Wallpaper* magazine at the airport when I boarded the plane to Geneva, and it was there again in-flight, on the back of BA’s business magazine —

“You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation” with the accompanying photograph of the perfect father with the perfect son or the ideal mother with the ideal daughter.

A few months before my trip to Switzerland, I spoke to Tim Delaney, the chairman of Leagas Delaney, the English advertising company responsible for a campaign that’s hardly changed in 20 years. “You have a strong sense that it’s a natural bond between the two people,” Delaney said. The ads are successful “because of continuity. In the company itself, the family ownership, the design ethos — the watches come from somewhere, they don’t just turn up.”

Continuity does seem to be the key to all this. When I ask Stern about the problems facing the Swiss watch industry (caused primarily by currency fluctuations and a downturn in orders from China), and when we touch upon Brexit, he explains it is all about holding one’s nerve. “In the short term, it affects us, but in the long range, no. Maybe with Brexit it will go a little bit down, but if I look at the graph 10 years ago, we were here [points low] and now we’re here [points high]. So, to go a little bit down is logical. It will remain a bit flat now, and we have to be creative. I’m not scared at all.” The downturn has certainly not affected Patek auction prices. In November 2014, for example, Sotheby’s sold the unique “Henry Graves” Supercomplication pocket watch from 1933 for CHF23,237,000 (about £18m), a world record. Since 2000, 14 vintage Pateks have sold for more than £2m.

The conversation spins back to the next generation; this is nothing if not a story of pedigree and inheritance. “My children,” he jokes, “should I leave them a thousand, a million, a billion? I don’t want to just spoil them and say, ‘I keep one billion for you, your life is OK, don’t do anything, just drink alcohol, take drugs and enjoy!’ I don’t think it will be good, you know?”

He remembers showing a watch to his sons when they were younger, “and it was funny for them: ‘How do you charge the watch — where do you put the plug?’” But now they understand a little more. The craftsmanship is all, he says. “It’s our education that makes us like this, not the business. I’ve been taught not to be really aggressive and greedy. I don’t think we should be much bigger. My target is not to reach a million watches. The target is to remain independent, and to continue to make the finest watches in the world and, when I retire, for the spirit to remain the same.”