Piet Oudolf is worried about his garden, and with good reason. Who wouldn’t be rattled if a snowstorm had damaged their garden so badly that the plants were completely crushed by the snow? Even so, it must be particularly galling when that happens to someone like Oudolf, the 73-year-old Dutchman who is not only hailed as one of the world’s leading garden designers, but who prides himself on using his skill and knowledge to create gardens that flourish the whole year round, whatever the season.

“Normally, at this time of year, the grasses stand tall and you’d see beautiful plant skeletons,” says Oudolf on a crisply wintry day as he surveys the carnage of snow-flattened foliage in the three acres of former farmland near the village of Hummelo, in a rural area of the eastern Netherlands, where he has lived and worked for over 35 years.

“This is the first time that this has happened in all the time we’ve lived here,” Oudolf continues. “The garden always looks very wild at this time of year, and I don’t mind that. But look at it now… still, you can still see the hellebores in flower, and soon the snowdrops will come, then the crocuses and the first leaves on the trees.”

The snow-crushed garden plays a critical part in Oudolf’s work as a living laboratory where he has tended and studied thousands of different plants to see how they respond to changes in the seasons, weather and light, and whichever other species they are close to. It is there that Oudolf, a lanky figure with a weather-worn but delicate face and thick, white hair with a long Forties-style side parting swept over his head, has acquired the deep knowledge of horticulture that has enabled him to design some of the most influential and beloved gardens of our time.

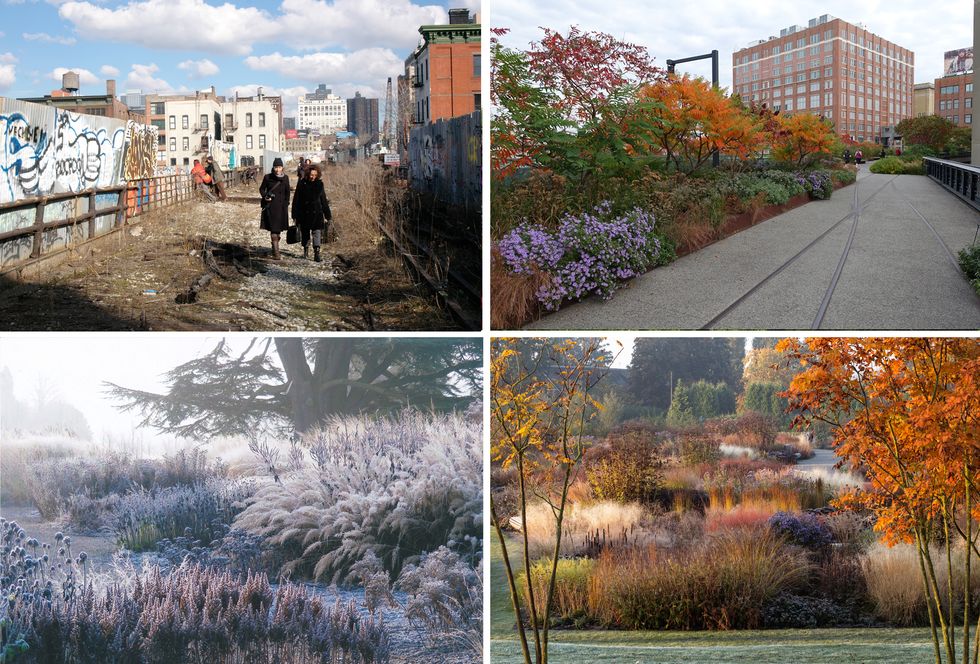

Every year, some six million people see the native US plants, grasses and trees Oudolf has planted on over 2km of disused elevated rail road that has been transformed into the High Line in New York. Oudolf Field, the flowering meadow he created at Hauser & Wirth’s art gallery in Somerset, draws hordes of garden and art lovers to a formerly derelict farm near the quiet town of Bruton. A highlight of the Serpentine Gallery’s annual pavilion programme in London’s Kensington Gardens was the temporary garden Oudolf devised in 2011 inside a pavilion designed by the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor. “It was magical,” recalls Hans Ulrich Obrist, artistic director of Serpentine Galleries. “Piet was invited to design the garden four months before the opening, but the magician in him made it look as though it was a monastery garden that had been there for years and years.”

Most of the great garden designers of the past were renowned for creating visual spectacles, and designed accordingly. They focused on the colours, shapes and other formal qualities of plants, shrubs and trees in order to combine them as appealingly as possible. Oudolf dismisses this approach as “decorative”, a word he seems incapable of saying without snarling. His focus is on how plants behave and evolve, rather than what they look like, and on constructing planting schemes from hardy perennials, which will last year after year, rather than removing and replacing dead foliage. By researching so many varieties of plants so rigorously and observing them growing in his nursery, Oudolf has introduced fellow gardeners and landscape designers to the charms of long obscure species, and helped to revive the general interest in wild flowers and grasses. The current fashion for straggling, seemingly wild, naturalistic gardens is in no small part down to him.

“I swear Piet is half-plant like Groot, that dancing tree from the Guardians of the Galaxy movies,” says Ricardo Scofidio, founding partner of Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the New York-based architects with whom Oudolf collaborated on the High Line. “And like Groot, Piet also has a heart of green.”

Half-plant or not, Oudolf’s discovery of gardening was surprisingly random for someone who is now so steeped in it. He was born in the Dutch city of Haarlem, where his parents ran a bar and restaurant. After leaving school, Oudolf moved from job to job, ending up at a garden centre, where the work kindled his love of horticulture. “After six months, I was seriously interested and wanted to learn more about it, so I bought lots of books,” he recalls. “Then I went to school for four years to study plants, trees, shrubs, contracting, design: everything I needed to become a professional contractor.”

By then, Oudolf was married, to Anja, and they had two young sons. To support the family financially, he continued to work in the garden centre during the day, and studied at night. Oudolf then started a business as a garden designer and contractor, running it with Anja. At the time, he was obsessed by the classical style of English gardens, such as the one cultivated by the late gardening writer Christopher Lloyd at Great Dixter in East Sussex. “I liked the classicism of gardens like Dixter,” he notes. “Then my interests moved on and I wanted to add more spontaneity.”

He wasn’t alone. Through his reading, Oudolf had learned of the iconoclastic gardeners who were dedicated to working with wild plants, starting with the 19th-century Irish writer, William Robinson, author of the self-explanatory book, The Wild Garden. Oudolf also admired the pioneers of a modern approach to garden design in the mid-20th century. Among them was his compatriot Mien Ruys, who designed gardens for the public, often on cramped sites with inhospitable soil, in the light, airy, utilitarian spirit of modernist architecture. Another inspiration was the brilliant Brazilian designer Roberto Burle Marx, whose tropical modernist gardens were steeped in his research into native Brazilian plants conducted in his nursery near Rio de Janeiro and on his expeditions into the rain forest, where he discovered several previously unidentified species.

The work of Burle Marx and Ruys helped to convince Oudolf that it was possible to define his own interpretation of garden design, encouraging him to continue his botanical research. “I saw a lot of wild plants that behaved very well and could easily be used in gardens,” he notes. “So we started to collect these and other underrated species. We hardly ever saw sanguisorbae or filipendulae in gardens in those days, and grasses were almost totally neglected. We brought in a whole range of grasses to create different emotions and to give a wilder look to the gardens.”

Oudolf put his ideas into practice in the gardens he designed and made for clients. However, by the early Eighties, he felt increasingly frustrated by the difficulty and, in many cases, the impossibility, of obtaining all of the plants he wanted, and decided to buy enough land to grow them himself. Eventually, he and Anja found a plot of the right size in Hummelo that they could just afford, moved into the farmhouse with the boys, and began the arduous process of establishing a nursery. “We travelled all over Europe to collect plants and bring back seeds from botanical gardens to plant,” Oudolf recalls. “Slowly, our nursery became well known for the range of plants we were growing and people came from all over — England, Germany, everywhere — to see what we were doing and to buy plants from us.”

During the early years in Hummelo, Oudolf abandoned his design work, partly because the couple’s new home was too isolated for them to meet prospective clients, but also because setting up the nursery and monitoring its contents took up so much time. “Trial and error, it’s the only way you can learn about plants and it’s a slow process,” he notes. “We’ve spent years experimenting with different plants and plant communities to learn about them. Some plants are short-lived and die after two or three years. Others live for 25 years, always behaving well, while others are so rampant that after a few years they’ll have taken over everything else. It was only by growing plants from seeds, and studying their behaviour, that I could use them in other gardens without too much trouble.

Throughout the Nineties, Oudolf established a reputation in horticultural circles as an exceptionally knowledgeable plantsman, and started designing again. A landmark was the creating in 1997 of the new Millennium Garden at the Pensthorpe Natural Park in Norfolk, which was his largest project to date and his first in the UK. Oudolf strove to create a garden that changes throughout the year yet always looks intriguing and engaging, while sitting comfortably within its rural surroundings. So popular was it that Pensthorpe invited him to redesign it in 2008, and to oversee its replanting the following year.

By then, Oudolf had completed a major public commission in the US in the flower beds of the Lurie Garden, which opened in 2004 at the southern end of Millennium Park in Chicago. The beds are now filled with 35,000 perennials in more than 200 varieties of local prairie plants. After Lurie Garden, he started work on another American project, the High Line.

Working in collaboration with the landscape architect James Corner of Field Operations as well as Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Oudolf was responsible for designing the High Line planting scheme. His brief was to evoke the wild flowers that had run riot on the old railroad during its years of dereliction. Eager to use native American plants, he searched for suitable prairie, meadow and woodland species, whose changing colours, textures and shapes would ensure that even the most frequent visitors to the High Line would see something different each time they went, even in winter. “Not every plant is interesting all year long, but one that blooms in June or July and then dies down may still be attractive because of the skeleton, the seed heads and so on,” says Oudolf. “It’s about the character of the plant, what they do after flowering and what they can do for other plants. And most grasses look good in winter. Panicum is a good example, or joe-pye weed, which has strong skeletons.”

To Oudolf, the High Line remains a work in progress, and not just because he has yet to finish the planting scheme for the northerly stretch running past The Shed, a cultural centre, which is currently under construction in the Hudson Yards area. He pays regular visits to assess the planting scheme and to adjust it to allow for the growth of some plants and trees, and other changes. “Under Piet’s direction, the High Line is a landscape of visual delight in constant seasonal change,” says Ricardo Scofidio. “I can’t imagine that Piet will ever see his work there as finished or complete.”

The High Line sealed Oudolf’s reputation worldwide, and he has since received so many offers of work that he can pick and choose which ones to accept. The giant flower bed he designed inside Zumthor’s Serpentine Pavilion is one of his favourite projects, not least because, rather than designing a garden to develop over time, he had to create one that would look mesmerising from the start. “The timing was crucial,” he explains. “If the planting had failed we’d have had nothing, because there would have been no time to make it better. Luckily, it was good from the beginning.” A friend who worked at the Serpentine that summer said that each day brought a new surprise as yet another extraordinary-looking plant would have appeared or flowered overnight.

“One of the fascinating things about Piet is that he is deeply local, living with his plants in his nursery in the Netherlands, but incredibly fast at reacting to different contexts,” observes Obrist. “Peter Zumthor wanted a very wild garden with a real richness and diversity of plants — and Piet understood that immediately. He also understood Kensington Gardens, and what sort of plants would work there, because his knowledge is so incredible. He’s a walking encyclopedia of plants.”

When the art dealers Iwan and Manuela Wirth told Obrist about their plans to open a gallery complex near their country house in Somerset, he suggested inviting Oudolf to design the grounds, which include an old farmhouse yard as well as the meadow that eventually became Oudolf Field. “It looks majestic all year round because Piet sees as much beauty in the decay of plants as he does when they are in full flower,” notes Alice Workman, director of Hauser & Wirth Somerset. “In the summer, we have a stunning flowering meadow with combinations of grasses and swathes of brightly coloured perennials. In winter, the seed heads take on a sculptural appearance and the combination of these stark, dark silhouettes against the golden grasses is truly beautiful.”

Despite the fame and acclaim, Oudolf is still based at the Hummelo nursery, where he works in a modest, flat-roofed brick structure that houses his studio, while Anja runs the nursery, a gardener looks after it and a contractor comes in to take care of the hedges. From his studio, Oudolf looks out on one side across the nursery, which is open to the public during the summer, and over open farmland on another. The walls are lined with shelves bearing hundreds of reference books on horticulture such as Flora of the Chicago Region and The Hardy Geranium. There are stacks of CDs, and DVDs of his favourite films, mostly documentaries and features by directors such as Stanley Kubrick and Werner Herzog. Rolled up neatly are meticulously drawn plans of his gardens and planting schemes, complete with pictorial codes that identify the number, colour or type of plants. Oudolf starts the process by drawing his plans by hand before scanning them, and is renowned for his precision. The British designer Dan Pearson remembered visiting the High Line and being astonished to discover that the planting looked almost exactly the same as in the original plans that Oudolf had drawn several years before.

His current projects include a roof garden for Goldman Sachs’ new HQ in London and the grounds of a soon-to-be-completed Maggie’s cancer support centre designed by the architects Ab Rogers in Sutton, Surrey. He has also been commissioned to design planting schemes for a new botanical garden in Delaware and a public park in Detroit.

“Something new always seems to come up, something I hadn’t expected, like the High Line or the Detroit park,” says Oudolf, “and the passion never goes away. Plants are a phenomenon that you can never fully understand, because they are living specimens with their own characters. And every year is a new year in a garden. It isn’t like a statue that stays the same, but a movie with different weathers and different seasons. You only ever see a garden in a particular way for a very short time.”