James Knappett is one of only 22 chefs in Britain who currently hold two Michelin stars. The 40-year-old’s main restaurant, Kitchen Table in central London, serves a tasting menu that costs £300 per person, without drinks, which used to sound like a lot, but is now roughly the same price as heating your house for the evening. Knappett has trained alongside some of the greatest pot-shakers and tweezer-fiddlers of our age, among them Gordon Ramsay, René Redzepi at Noma in Copenhagen and Thomas Keller at New York’s Per Se. No mistake, Kitchen Table is a serious gastronomic destination, to an extent that, as its website prewarns, if you’re wearing a baseball cap, you will be politely asked to remove it. (What happens if you have on a fedora or, say, a Homburg? I’m not sure, but maybe just don’t.) Each course is based around a radically seasonal, hero ingredient, which might be wild cherries from Scotland, Australian black winter truffles or Cathedral City cheddar.

OK, not that last one. But I’m sitting with Knappett in the George pub just off Oxford Street in central London and he’s talking about those doorstops of Cathedral City in the burgundy packs with a reverence that I’m not sure anyone could have anticipated. Knappett doesn’t like Cathedral City in an ironic way, or a the-company-is-paying-me-five-figures-to-pretend-I-eat-this-stuff way: it’s genuinely what he has in his fridge at home. “Ah mate, two blocks of Cathedral City a week, easy,” he says.

Knappett is a surprise in a few ways: I had imagined he might be earnest and intense, a man with an immoderate fury towards people eating while wearing casual headgear. But he’s funny and unpretentious. He grew up around pubs — one his mum ran in Cambridgeshire and his uncle’s in Suffolk — and that’s still the food he craves. “People get shocked when they find out I like Heinz ketchup,” says Knappett, who has clippered brown hair and a beard, and has retained a soft East-Anglian burr. “What? Just because we cook fine food, they go all weird. I put ketchup on everything at home. And they’re like, ‘I bet you make your own?’ And I’m like, ‘I don’t, because I'll never make it better.’ Just like every person on the planet has tried to make Coca-Cola. Just don’t! You'll never beat it! Fentimans cola. No.”

That’s Fentimans “Curiosity Cola”, James, but still, take your point. Every so often, Knappett will wake up and drive from his home in north London to Tesco in Newmarket, Suffolk, for a full English breakfast. “I don’t tell anyone that,” he says. “Yeah, 75 miles I drive for that. I don’t want posh bacon. I don’t want posh sausages. I just need everything really normal. Tesco’s nails it.”

One time, when Knappett was at Newmarket Tesco, he bumped into Calixta Killander, the superstar of the regenerative-farming movement whose company Flourish Produce supplies biodiverse fruit and veg to many of the best restaurants in the UK, including Kitchen Table. “I was paying for my breakfast, and she turns around and goes, ‘I thought that was you,’” says Knappett, laughing. “And I was like, ‘You’ve got to be kidding! You didn't see me in here, seriously!’ And she replies, ‘Same. Deal?’”

“Normal” is a word that Knappett returns to often when talking about food. At one point, he picks up his mobile phone and thumbs through Instagram. “Have you heard of this place, Norman’s Cafe?” he asks. “These guys are friggin’ geniuses. That’s an ideal restaurant of mine.”

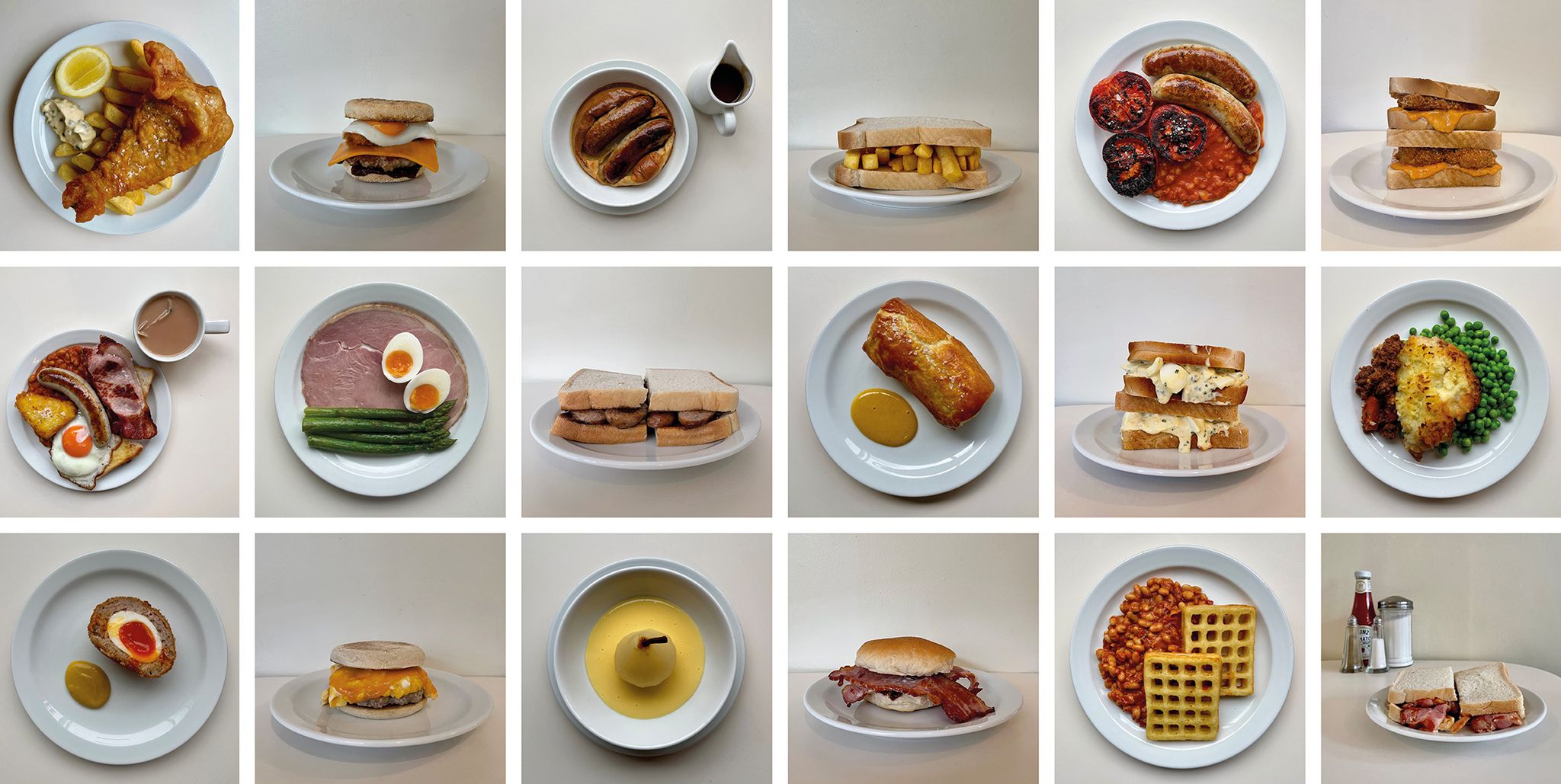

Knappett’s screen is filled with photos of food, mostly shot from above, on white plates against an uncluttered white background. Most of it looks disarmingly basic: there’s beans on toast, battered sausage beside a knoll of brown sauce, a few different iterations of the fry-up with a cup of tea next to it, bag left in. “It’s just a little caff in Tufnell Park and you can’t get in there, it’s absolutely packed,” says Knappett, scrolling through the pictures. “There you go... Sticky toffee pudding… Chicken nuggets, chips and beans... Battered Mars bar and cream for a dessert… Chip butty… It takes a bit of guts to do a chip butty.”

Norman’s Cafe’s captions on Instagram take a what-it-says-on-the-tin approach: “Ham, egg & chips” and then, usually, around 3,000 likes. It’s a directness that appeals to Knappett. “It’s not like you get there and it’s all, ‘We’ve got this flour from here... We’ve aged this for nine weeks… The chips are from here…’” he says. “You’re like, ‘I don't give a shit, mate! I just want a chip butty with some ketchup!’”

After leaving Knappett, his words — and his unapologetic love for what I would deem “crap food” — stayed with me. To be honest, it stung. I’ve written about cooking and restaurants, on and off, for around 20 years and that period has seen a dramatic transformation of the British food scene. As shoppers and customers, many of us have become obsessed with the provenance of what we eat, with a new lexicon emerging to elevate ingredients: “small-batch”, “craft”, and the ubiquitous “artisanal”, which can be found on everything from crisps to pasta to soda. I once saw it used to describe Andy Murray’s forehand.

We are talking about the arrival and rise of the “foodie”: a contender for the most objectionable word in the world and some of the most objectionable people, especially when they use the term to self-describe. These are folk who, if they buy instant coffee at all, it’s only to give to the builders who are working on their side return. They ascribe to a strict hierarchy of produce: bread should be sourdough, hand-kneaded over a period of days using just flour, water and salt, and never industrially produced sliced white. Chickens should be soy-free, totally free-range, no GMO, at least five months old and ideally known by first name. They buy books on fermentation (never crack the spine, naturally) and convince themselves they love kimchi, because it “goes with everything”. People who care more about the cost and the story of the food they’re eating than what it actually tastes like.

I know this person, because I kind of am one of them — no side return, yet, but always hoping. Certainly, I have to acknowledge that I am more likely to sell my kids to a stranger than buy a block of Cathedral City. But Knappett has given me pause: is the tyranny of the foodie over? In the midst of a cost-of-living omnishambles, who can afford to spend £9 on a pot of jam? And, when the world starts poring over Instagram posts of defiantly normal food, where does that leave the provenance snobs?

A few recent experiences had started to chip away at my food pomposity. At a talk by the great Swedish chef Magnus Nilsson I attended in 2018, he had gone off about how terrible sourdough was for sandwiches: “It’s full of holes!” was his general point. For a recent assignment, I went on a two-day road trip with Tom Kerridge, one of the other 22 British chefs to have two Michelin stars, and we subsisted almost entirely on Cadbury Heroes, chocolate digestives and Costa Express from service stations. In Heston Blumenthal’s new book, Is This A Cookbook? (spoiler: it is), my eyebrows arched when I noticed that he uses sliced white bread throughout the sandwich section.

These chefs didn’t believe in a hierarchy of foods, so why did I? Sometimes, you can just eat what tastes great, and not care about who made it, using what process. Often, our tastes will be nostalgic: the best meal of Knappett’s life was a 34-course feast at Alinea in Chicago, but the one he remembers most fondly is the prawn cocktail sandwiches thrown together by his father when his little sister was born, made from defrosted prawns, ketchup and salad cream, eaten in the hospital.

“Normal food” somehow feels right in 2022. We want value for money from food, especially when we eat out. Perhaps, we also desire the crutch of familiar food in settings that feel comfortable. Knappett certainly recognises that. In addition to Kitchen Table, he has recently taken over the food offering in two London pubs: the Cadogan Arms in Chelsea and the George, where we meet. The menus in these places are made up of unfussy and familiar classics: prawn cocktails, roasts, Ploughman’s. The only frills are on the doilies that make an appearance under some of the dishes.

Knappett loves fine dining, the care and attention that goes into every aspect of the experience. But he also enjoys not having to fixate on those details. “At the pubs, you don’t have to worry about tablecloths or the spacing on the wine list and all the little things that we think we need to look at,” he says. “Crazy things, like asking, ‘Has somebody checked the toilet roll?’ every time a guest has gone in.”

The “friggin’ geniuses” behind Norman’s Cafe, the bastion of normal food so praised by Knappett, turn out to be chef Richie Hayes and everything-else Elliott Kaye. They met a decade ago when they were both in their early twenties and worked at Workshop Coffee, one of London’s best roasteries (“roastery” surely belongs on that list of heinous foodie words), and started talking almost immediately about having their own place one day. The original concept was to open a traditional greasy spoon, like the ones they had spent their teens in, but to serve decent coffee alongside the fry-ups. Neither of them had any money or very much experience in the hospitality industry, so they decided to work and save. They wanted to learn from the best, so they found jobs in Shoreditch restaurants Lyle’s, ranked number 33 in the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list in 2021, and Leroy, which also has a Michelin star.

But fundamentally, the core concept never changed: Norman’s Cafe — the name comes from Hayes’ great-grandfather — is a place where you can get a fry-up and a good cup of coffee. They found a site squished between an upholstery shop and a hair salon on the main drag through Tufnell Park, north London, and renovated it themselves with their girlfriends, opening for business in November 2020. “This food is not designed to be like food you’d find in a restaurant,” says Hayes, who has intricate sleeve tattoos and wears a stripy butcher’s apron and Birkenstocks. “It’s just designed to be home food. I want the meals to feel like they’ve been made by my nan, not by a Michelin-starred head chef. That’s it, really.”

The success of Norman’s Cafe may, in fact, just come down to a sprig of cress. When Hayes was finalising the menu in the winter lockdown of 2020, he had to decide how to finish the dishes. All his training and instincts were screaming “Garnish!” but something told him not to. “I had to really hold back on putting cress on some things,” says Hayes. “Like not fancying something up that shouldn’t be fancied up. So when I first wrote the menu for this place, it was using all the most amazing ingredients. But then, I thought, ‘We need to strip this back a bit, man. We can’t overcomplicate what it basically is. It is what it is.’”

More than that, though, Norman’s Cafe perfectly blends high and low: this allows it to appeal to both the food snob who follows them on Instagram to hordes of hungover locals who crawl in on weekend mornings craving a fry-up and a Coke. Hayes and Kaye splashed the cash on a top-of-the-line La Marzocco espresso machine, but there’s a fridge loaded with cans of Stella Artois and Kronenbourg, and £1 cartons of juice. When Norman’s first opened, they had a tap serving Camden Hells lager, from the nearby Camden Town brewery, but Stella in cans sold better.

“Our beans on toast is a prime example,” says Kaye, who is in a grey Champion sweatshirt and — avert your eyes, James Knappett — a Ralph Lauren cap. “We make the beans in-house — it’s a rich tomato sauce that we slow cook for hours and hours. Lots of time and effort goes into it. Then, we just put that on a base of sliced white bread, and it’s the perfect balance of flavours. If you put that on sourdough, it wouldn’t be beans on toast, it would become something where you’re trying too hard.

“If Norman’s did sourdough, no one would like it,” he goes on. “That’s more of an Australian brunch vibe, which is not really what we are.”

The Norman’s Cafe beans on toast, which costs £5 and is served with a slice of melted Red Leicester, has become somewhat notorious after Kaye prepared it on Channel 4’s Sunday Kitchen for presenters Tim Lovejoy and Miquita Oliver in August. The dish went down well with guests on the show, who included Lily Cole and Keren from Bananarama, but the next day, the tabloid newspapers were furious. The Sun hosted an online poll asking whether it was acceptable for such a basic dish to appear on a hallowed cooking show: 45 per cent of respondents checked the box, “Absolutely not. It takes the mickey.” Another 32 per cent huffed, “Maybe with a twist, but not that basic.”

“When you go on TV and serve beans on toast, I guess some people aren’t going to get it,” says Kaye, with a smile. “But the haters — I feel like if we put cress and stuff on, a lot more people would be like that.” In north London, though, the non-believers seem to be losing the argument. Norman’s Cafe opens at 10am and there’s usually a queue, especially on weekends. “People are happy to queue an hour and a half for a bacon sarnie,” says Kaye, shaking his head. “It blows my mind, but it’s great.”

In a sense, this makes no sense. In that time, you could go to the shop and buy bacon, sliced white and ketchup, go home, cook and eat it and wash up; save yourself time and money. So, what’s behind the sudden, rapturous interest in “normal food”? Does it speak to our desire for comfort in difficult times? Do we want the community of eating in a restaurant setting without breaking the bank?

Hayes and Kaye are as bemused as anyone. “It definitely wasn’t planned,” says Hayes. “Maybe we were just in the right place at the right time. That’s all.” Kaye adds, “Honestly, we never really thought about it, we had the idea so long ago. If we could have done it 10 years ago, we would have. Norman’s came out of the money that we saved and we didn’t have a huge amount of it.”

It’s midday now, Norman’s is full, and Hayes and Kaye are all hands to the pump. I order a chicken-escalope sandwich with spicy mayo and Red Leicester, with a side of baked beans and chips, and take in the scene. On the wall, there’s a blackboard with the menu on it, a photo of Bobby Moore being carried on his teammates’ shoulders in 1966 and a vintage Guinness poster. On Formica tables, shakers of salt, pepper and sugar nuzzle up against bottles of Heinz ketchup. In the room is a properly eclectic crowd, something you hardly ever see in restaurants anymore. There’s young and old, cool and not. On one table, four art students take pictures of the condiments and ask for oat milk in their teas. In a corner, a solo woman in her sixties waits for her fry-up, not even looking at her phone. A table of American tourists clear their plates and talk loudly.

I pick up the sandwich. The bread is bouncy, the chicken’s golden, the cheese is hi-vis orange and the mayo’s already seeping out the sides. I take a bite and I’m overwhelmed by… what? Is it the nostalgia? The saturated fats? The fact the bill is going to be £11 and not £60? Whatever it is, I realise I haven’t enjoyed a meal in a restaurant this much in years.