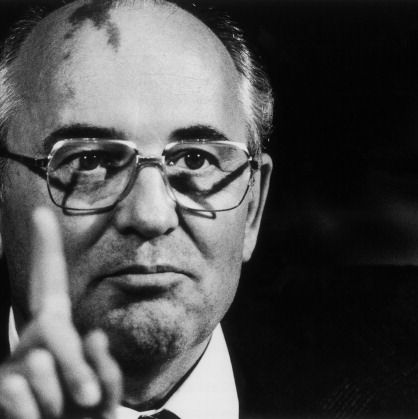

God help me, this is the prevailing image of Mikhail Gorbachev that has stayed with me since he faded from the international scene. Pizza Hut in Moscow needed a pitchman, so why not the guy who set in motion the collapse of the USSR and allayed the fears (at least for a while) of all of us children of the Cold War, the Berlin Wall and the Missile Crisis? And what could say more about the triumph of global capitalism than a Pizza Hut in Red Square? (In addition, the commercial gave the final boot to one of Ronald Reagan’s dumbest lies: that there was no Russian word for “freedom.” Note please the subtitle for “svoboda.”)

His is a completely strange legacy because the Soviet Union in the late 1980s was a completely strange place. Its economy was in shambles. Its military had limped out of Afghanistan. Western culture was besieging it on all sides, blue jeans and the Beatles doing what 500 CIA assets couldn’t. And the vassal states in eastern Europe were beginning to realize that the threats made manifest in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968 were now hollow ones. Pope John Paul II was agitating in Poland. It was an empire that was tottering without anyone firing a shot, grown so sclerotic that it could barely move to defend itself, and its people not entirely sure that they wanted it to do that anyway. When Alaric sacked Rome in 410, he didn’t leave nifty Gothic bistros behind. Built on the bones of the Soviet Union was a place to get a large pie with peppers and onions.

At the beginning, all Gorbachev wanted was to open the Soviet Union up to the world (glasnost) and restructure its institutions (perestroika) into something resembling a modern political entity. But the momentum he unleashed was something he could never control. As Andrew Nagorski notes in The Daily Beast in his reminiscence of a trip with Gorbachev to Siberia:

Still lionized in the West for his role in helping end the Cold War (he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990), Gorbachev was detested by many of his own countrymen, often for completely contradictory reasons. “He destroyed a great state,” worker Vasily Ivchenko told me as he watched the famed visitor tour his Novosibirsk machine-tool factory. “The collapse of the Soviet Union started with Gorbachev, and Yeltsin continued with what he started.” In 1993, a mock court of hardliners condemned Gorbachev to “eternal damnation and infamy.”

Gorbachev’s protestations that he was trying to steer a middle course and to avoid the pitfalls of “shock therapy,” as he branded Yeltsin’s program, only reinforced the view of his opponents on the other end of the spectrum that he never committed himself fully to a new political course. “Gorbachev was a loser who, despite his youth, was a representative of the old generation,” said Sergei Grigoryants, a leading human-rights activist and former political prisoner. In short, Gorbachev alienated the hardliners and reformers alike: Depending on who you listened to, he had gone way too far or not far enough.

What I also remember is that during his extended arms control negotiations with Reagan, the American right, especially its neoconservative element, went completely bananas. You may recall that the basis of the geopolitics spouted by Jeane Kirkpatrick, It Girl of the Project For A New American Century, was that “totalitarian states” like the USSR were incapable of reform and were very nearly invincible. Yet here was the biggest one of all completely falling apart before God and the world. As Reagan and Gorbachev inched closer to an agreement and the USSR inched closer to dissolution, George Will had an absolute cow in his Washington Post column.

Reagan's rhetoric has accelerated the nation's intellectual disarmament. In his seventh and eighth years, he has declared the Cold War over. He has done this by declaring that the Soviet regime had been readily transformed for the better by the sudden, inexplicable capture of it by a man (Mikhail Gorbachev) who supposedly is opposed to its 70-year-old expansionist tendency and rationale. That statement was bad enough. But worse was Reagan's statement that the Soviet regime's inherent tendencies were not radically wrong until the regime was hijacked by Stalin. Stalin, said Reagan, was not, as conservatives believe, an intensification of Lenin, but was merely an aberration…by succumbing so fully to the arms control chimera, Reagan made it impossible to conduct a coherent conservative foreign policy. Indeed, a case can be made for the proposition that, thinking only of U.S.-Soviet relations, a Dukakis presidency might be preferable to a Bush presidency of more Reaganism.

For all his faults—and they are vast and manifest to this day—Reagan at least knew when to take 'yes' for an answer. He and Gorbachev were able to deal with each other, even on matters that were more than a little…esoteric.

From the Christian Science Monitor:

[George] Shultz was talking about the Lake Geneva summit and mentioned the two leaders ducked out of a meeting to take a walk to a nearby cabin.

"I wasn't there...," Shultz said before Gorbachev cut him off.

"From the fireside house, President Reagan suddenly said to me, 'What would you do if the United States were suddenly attacked by someone from outer space? Would you help us?'

"I said, 'No doubt about it.'"

"He said, 'We too.'"

"So that's interesting," Gorbachev said to much laughter.

So there was that, too.

Gorbachev was a man for his moment. If his original plan was to keep an empire intact, he failed; but he helped create a space for a free Czechia, a free Hungary and dozens of other fledgling democracies, many of which are now under attack by the forces of the political right that Europe thought had died in the snows of Stalingrad. If those states are strong enough to fend off the current threats to their democratic governments, they owe a little of that to Mikhail Gorbachev, a man with whom you could deal, who died on Tuesday at the age of 91.