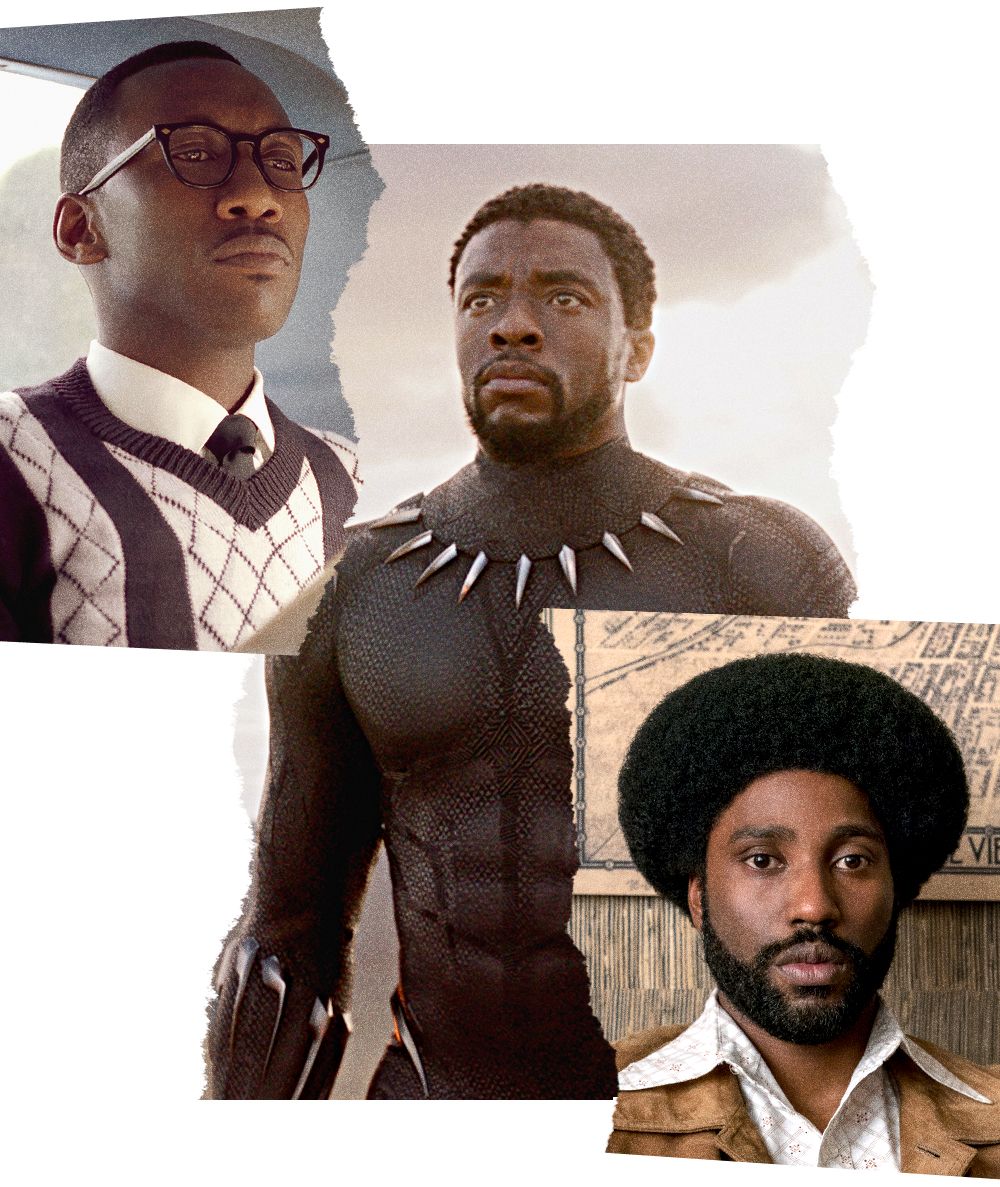

If you’re interested in narratives of Blackness in cinema, this year’s Best Picture Oscar nominations were something to celebrate—at least upon first glance. Three of the movies featured leading Black characters: Black Panther, BlacKkKlansman, and—ostensibly—Green Book. Alongside Roma and Bohemian Rhapsody, this trio of movies meant that a majority of the Best Picture nods celebrated cinema about people of colour, a win for “diversity.”

And yet, the three nominated films about Black people all feature seductively conservative racial politics—for when it comes to celebrating films about Black experience (much as it has historically done with rewarding Black performances), the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences likes to reward conservative political messages. The Academy heavily rewarded three movies, with differing degrees of subtly and overtness, that reinforced racial politics of inevitable black submissiveness (Black Panther), promoted violent policing (BlacKkKlansman), and upheld an American mythology of racial reconciliation devoid of accountability (Green Book).

At a plot level, Black Panther has an extremely conservative political message. As I’ve written before, the movie’s hero, T’Challa loses control as the ruler of the fictional African nation of Wakanda fair and square to Killmonger under its own rules. Killmonger is a bastard African American from Oakland, the birthplace of the actual Black Panther Party. Killmonger understands that vibranium—a valuable resource—has been extracted from Wakanda and weaponised by the United States. Killmonger vows to use the very African resource which has been extracted by colonialism to arm Black people around the world so that they can free themselves from global imperialism. But backed by a white CIA agent—and aided by the women of Wakanda, whose queer sexuality explored in recent comic book runs was ignored in the Marvel movie—T’Challa kills Killmonger’s plans for global Black liberation.

Even Chadwick Boseman told Ta-Nehisi Coates on the stage of the Apollo Theater that the character whose mask he donned was the villain in Black Panther, not its hero. And yet, the film itself pushes you to believe the reverse. “One of blackest things about Black Panther,” the writer Joel Anderson wrote on Twitter about the movie’s neoliberal final scene, is that instead of Killmonger leading a revolution, T’Challa “promised to build a community center and charter school.” The Academy is rewarding a kind of Democratic National Committee-style fantasy, in which favors racial management by technocratic means over racial liberation from militarism.

But if Black Panther is somewhat subtle in getting its audience to unconsciously cheer the CIA on to contain an uprising against racism, Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman is more heavy-handed in getting its audience to cheer on the police to containing justifiable Black anger in America. Based on a “true” story—a trope Hollywood loves to evoke while marketing fiction—BlacKkKlansman is, on one level, an interracial buddy comedy. Colorado Springs police officers Ron Stallworth (John David Washington) and Philip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) team up to do the serious work of infiltrating the Ku Klux Klan while simultaneously comically interacting like Mel Gibson and Danny Glover in Lethal Weapon or Leslie Nielsen and O. J. Simpson in The Naked Gun.

In an age when Americans should be more angry than ever that police kill more than 1,000 people a year (with young Black men being nine times more likely to be killed than any other Americans), BlacKkKlansman has a disquieting political agenda. Before the cops even take on the Klan, Stallworth is hired as the first black Colorado Springs police officer specifically to infiltrate a local group of Black student activists when Kwame Toure comes to speak to them. Like all Spike Lee joints, BlacKkKlansman is cinematically fascinating and intriguing, and the scene where he shoots floating black faces listening to Ture (aka Stokely Carmichael) is among the most beautiful in his oeuvre.

And yet, Stallworth is sent there to spy on Black student activists. Stallworth tricks one of their leaders, Patrice (Laura Harrier), into dating him without telling her that he’s a cop. A dear cinephile friend has argued with me that Patrice, who says she can’t be with Stallworth because he’s a cop near the end of the movie, is the moral voice of the film; but, as in many Spike Lee films, the female character doesn’t get the space she deserves. Whether she actually leaves him is unclear. The overarching message to me was that cops sometimes need to monitor Black protesters to keep them from getting too radical—a dangerous message given how the FBI conspired to destroy the Black Panther Party and how it continues to monitor Black Lives Matter activists. That Lee recently earned $200,000 to create a propaganda campaign “to strengthen the partnership between the NYPD and the communities it serves” is also unsettling. It is a very different world in 2018—when Hollywood lauded cinema was encouraging us to worry about the inner world of police themselves—than in 1991, when Lee was lauded for depicting the interior world of someone killed by the police in Do the Right Thing.

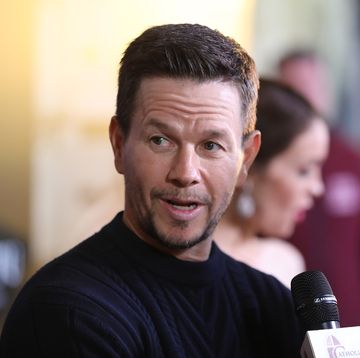

Do the Right Thing was infamously snubbed for Best Picture and Best Director, the same year the Academy awarded its top prize to Driving Miss Daisy—which brings us to the film with the Oscar movie with the most regressive anti-Black politics of them all: Green Book. Directed by Peter Farrelly, a white man more known for gross-out comedies and allegedly showing off his penis at work to his subordinates, the movie is not actually about the Negro Motorist Green Book itself, the guide Black motorists used to navigate the segregated south. Nor was it really about the Black and gay piano virtuoso Don Shirley (Mahershala Ali), but rather someone who drove for him for just two months: Tony Vallelonga (Viggo Mortensen).

Green Book is a white saviour movie at its most crude and unimaginative. As the white man, Tony is the arbiter of authenticity who teaches Don how to listen to Black music, how to eat Black food, and what it means to be Black. I think I cringed the most when Don, in the pouring rain, cried to Tony about white people not liking him because of his and Blackness and Black people not accepting him because of his sophistication. Or maybe it was when a nice police officer was trotted out near the end to show that not all cops are racist. Or maybe it was when a white man with a gun saved Don from “Black-on-Black crime.” Or maybe it was when Don actually started driving his exhausted chauffeur in their last car ride, performing Driving Miss Daisy cosplay. Or maybe it was when Don deferred the most important decision of the film—whether he would play piano at a segregated restaurant which wouldn’t let him dine there—up to Tony. Or maybe it was when Don—a rich, cultured gay man who lived upstairs from Carnegie Hall—lived a life so lonely, so utterly devoid of friends, so empty of love, that he had to go running to the straight white man’s family for comfort on Christmas.

Or maybe it was how loudly the audience laughed around me when white characters would say “chink” or “jungle bunnies,” and how they guffawed at Don daintily eating fried chicken. For the most disturbing thing about how Green Book is that it wasn’t relegated to being a movie with all of the flourishes of a basic-cable production, but that it has been embraced by Hollywood as perhaps the best movie of the year. In 2016, at a time when the Black Lives Matter movement felt on the ascent, Mahershala Ali won an Oscar for Moonlight, a Barry Jenkins movie which paid no mind at all to the white gaze while foregrounding Black, queer intimacy. Just two years later, Ali stars in a film that puts a Black gay genius’s life story in the literal backseat to a guy named Tony Lip.

While the politics of these three films are all conservative, they’re not equally so. Green Book is trash. BlacKkKlansman is muddled and deceptive. But despite its plot, as a work of cinema, Black Panther is a majestic movie. Its many artisans made a rich, beautiful, multi-layered movie open to many readings—the kind of movie which does actually deserve to be crowned Best Picture. But of these three movies, it seems the least likely to win (and its director Ryan Coogler wasn’t even nominated).

At the end of the day, the Oscars are a sales pitch to the world. Movies are a kind of myth-making, and the Oscars are not just a chance for the Academy to sell those myths to us, but also to tell the myth of Hollywood itself: a creative industry that corrects society’s failings by promoting “diverse” storytelling, But what does it mean that Hollywood is selling these myths of Blackness that are limited in their expression of Black freedom?

When it came to stories of Black people this year, the Academy is selling the myth of a noble, CIA-backed king, of chivalrous policemen, and of a benevolent racist. If we can just not think too broadly about liberation but settle for technocratic solutions, and if we can just get along like a pair of interracial bros, maybe we can just all get along! Giving a directing Oscar to Lee will allow the Academy to credit one of the greatest Black directors of his generation by rewarding his most racially regressive movie. Giving an Oscar to Green Book will not only let the Academy return to centring whiteness in movies it rewards in ways Moonlight did not, it will also signal that, in honouring a Peter Farrelly movie, the Academy is not beholden to the #MeToo movement.

This year’s Best Picture nominations may look diverse. But who actually wins may show that the class, racial, and gender politics reflect a revanchist impulse within Hollywood.

Steven W. Thrasher is a doctoral candidate in American Studies at New York University and regularly publishes in the New York Times, The Guardian, BuzzFeed News, and The Nation. In June, he will become the inaugural Daniel H. Renberg chair in media coverage of sexual and gender minorities at Northwestern University.