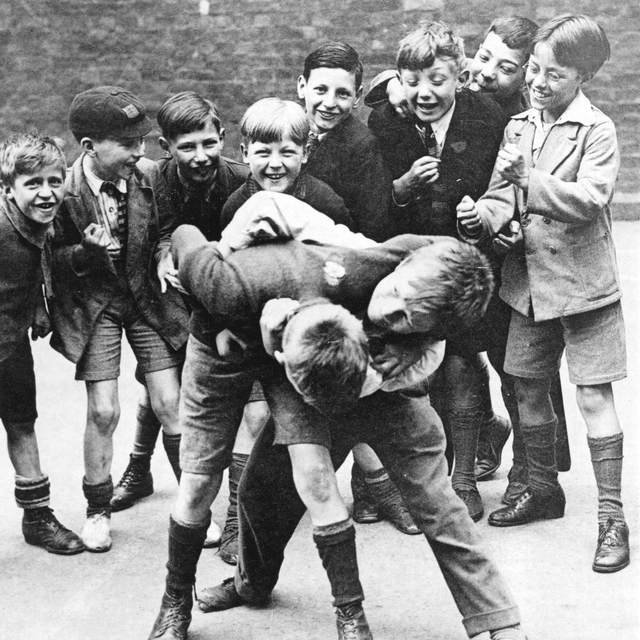

For the male of the species, the only real test of character, on the average day at school, was whether or not you could stand being punched in the face by Sammy Begg. You could send a sick note in advance, you could feign rabies, you could hide behind your mates, you could claim to be a conscientious objector or an envoy of the Dalai Lama, but eventually — at the bus stop — your appointment with Sammy would arrive. In the lexicon of old Ayrshire, you were about to get a “doing” — a thrashing, a pummelling, a pasting, a kicking — and your nascent wit was mere chaff to the wind as you faced the bull of Kilbirnie.

Now, my family had form. We weren’t all the shitebag I was. My grandfather was a spongeman for the Glasgow pugilist Benny Lynch, and he packed a fair punch himself, going 12 rounds with the roughest guys in the Gorbals. Back in the day, my father’s view of any potential disagreement was to punch first and talk later, or rather, to make all talk irrelevant. He would call out our friends’ dads to settle a game of rounders. My brothers were handy enough, though peaceniks-in-waiting. The only genuine shitebag in the family (including my mum) was me, who wanted to call in Acas, the arbitration service, the local priest, or the United Nations every time somebody asked me for a square-go.

‘I don’t want to fight, Sammy. I’m a lover, not a fighter.’

‘Ye’r a wee shitebag prick,’ he reasoned.

The rest is a blur. Or a blank. I can only assume that my late attempt to refer my assailant to Hazlitt’s On the Pleasure of Hating quickly failed.

There comes a time in life when you feel confident you will probably make it through the day without having a fist-fight. My friend Jack goes to the gym every second day and he’s built like a brick shithouse. “I’m all about the peace,” he tells me, “but you have to admit, it’s a bit insulting for a guy to realise that the time is coming when people would rather give up their seat to you than punch your lights out.”

“Can’t say I’m devastated by that,” I replied.“Hmmph,” he said. (I think he’s on steroids.) Men come in different sizes, of course, but the shitebag will prevail. Another person who wouldn’t have agreed with me is the late Norman Mailer. I suppose he represents a generation of writers out of step with current notions of woundedness, but he took from his hero Hemingway a willingness to strip down to the waist at a second’s notice and spar with anybody who happened to feel his use of the semi-colon was not all that. By the time I met Mailer, in Provincetown, Massachusetts, he was in his late seventies and a pussycat. He was lovely. But he still believed that a man must test his passion and his nature via the fist-fight. He admitted that he’d attended Truman Capote’s famous Black and White Ball in New York in 1966, but spent the whole evening asking politicians and writers to step outside or else arm-wrestle at the bar.

All silly, of course. But a bit of silliness can be a remedy in certain circs. I’ve been studying knife violence for a big project, going all over London and following huge court cases that lasted years. My one resulting certainty is that a couple more fist-fights and a lot fewer machete-wieldings might save a generation of young Britons. One day, we might even consider the fist-fight to be a crucial element in an orderly society. This is an embedded idea. Look at any British soap, where a bit of impromptu but quite necessary boxing acts as

a punctuation mark, the natural settlement of many a storyline. (I can still remember when Ken Barlow lamped Mike Baldwin on Coronation Street; it seemed, in 1986, as if the spirit of ancient justice had just visited our living rooms.) This was a country in which a person behaving like an arsehole could expect a slap, and I’m not sure that wasn’t better, more natural and fundamentally more reasonable, than today’s kids tooling up for warfare over “respect”.

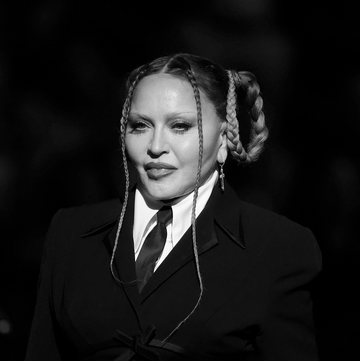

On the other hand, I hate it when good comedy is turned into a brawl just because people take themselves too seriously. At this year’s Oscars, there were at least three reasons to dislike the very-keen-to-be-liked Will Smith after his famous incident. One, it wasn’t a punch but a flaccid old slap, like a wet fish landing on a rubber mat inclose proximity to a working microphone. If you’re going to dig somebody up for insulting your wife, clench your fist and knock their teeth out. That shit was lame. Two, the “joke” wasn’t funny. It wasn’t like one of those Ricky Gervais truth-bombs that makes you worry that everybody’s going to rush the stage at once with pitchforks and copies of O Magazine. It was a joke about a haircut. And three, Smith was beating up on a working man with a show to present. For proletarian reasons, I’m not into off-duty people taking the fight to the gainfully employed. Shame on you.

Still, I’d sooner have a cup of tea. And if Will Smith (6ft 2in) had come for me like that, I’d instantly have contorted my face into the peace symbol and let off four doves. The life of the shitebag is dependent on quick, imaginative thinking, plus epic begging for forgiveness, and I would have known what to do. When in doubt or danger, I reach again for the inimitable Hazlitt, who protects me against all comers. “Reader, have you ever seen a fight?” he wrote in his deathless essay on a bout of fisticuffs. “Confidence is half the battle, but only half.” The other half is made up by a combination of skill and determination. These are matters I have come to know about via intimate acquaintance with their opposites.

Andrew O'Hagan is an author and Esquire editor-at-large; his most recent book, Mayflies, is out now in paperback