On a crisp Tuesday in November, East London’s Wapping Wall is quiet but for a few joggers and a modest queue of customers for a hole-in-the-wall delicatessen. Suddenly, in a blur of animal print and vintage workwear, a quartet of fashion people emerges from a restaurant, meticulously layered and coolly cocooned in cigarette smoke.

At the group’s apex stands Charaf Tajer, the founder and creative director of Casablanca, the ultra-modish luxury fashion brand that has, in three short and surpassingly strange years, gone from sitting-room startup to serious industry player.

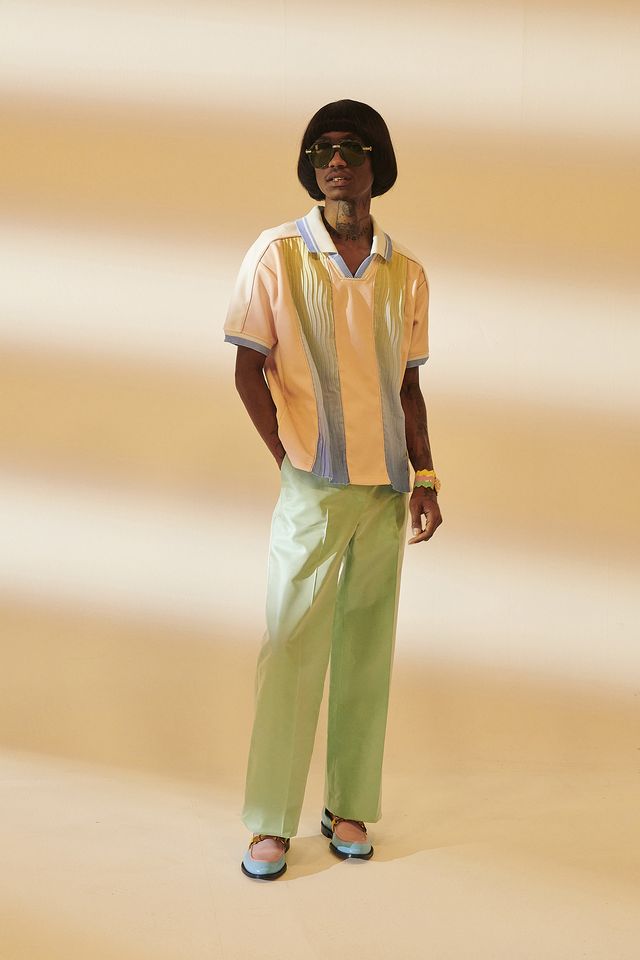

Tall, with a boyish face aged only by a very neat, gently greying beard and oversized tinted spectacles, Tajer, at 36, is among the most influential new creatives in high-end fashion. His label’s aesthetic - a sort of sporty sexiness, slightly kitsch, very French - encompasses silk shirts, tennis whites, terry towelling, short shorts, flares, sweatpants and melodramatic tailoring. A pair of tube socks, the brand’s ‘entry point’, will set you back around £25, while the most expensive pieces run into the thousands, putting Casablanca on a par with Gucci or Saint Laurent.

The prints – applied to silks or denim or any fabric that will hold them – are Casablanca’s calling card. Everything from Parisian street scenes, psychedelic landscapes, and geometric patterns fit for the Overlook Hotel. Casablanca’s partnership with New Balance — expressed in lurid, oversized takes on the shoemaker’s classic runners - has been perhaps the pre-eminent high/low fashion collaboration of the past few years. The company has gone from quite silly to completely serious, and somehow managed to hold on to the silliness.

The label began, inauspiciously, in Tajer’s mother’s sitting room in 2018. The son of Moroccan immigrant parents, he grew up between Paris and Casablanca and when clothes eventually materialised as a form of expression for Tajer and his friends, the glamour of one city melded with the vibrancy of the other. “When I was a teenager, we started dressing mainly in Hermès, Lacoste and Cartier, with some Nike Air-Max. We said we dressed like ‘doctors who play tennis,” Tajer says. “We knew we were kids with blue-collar parents, but [fashion] was a window into a dream. More like an escapism. It was the beginning of my fashion life.” His style was boldly ‘luxurious’. Big sunglasses, silks, country-club knitwear, but resolutely Gallic, too.

We are talking in the boardroom of his new London HQ, overlooking the Thames. With 40 or so staff, the company recently outgrew its original Hackney studios; Casablanca is based in London for creative reasons, says Tajer: “Because of the Royal College of Fashion, people are so well trained [in London] and it makes a massive difference to. In Paris it was so complicated.”

In 2008, Tajer was part of the team that founded streetwear boutique and eventual streetwear brand Pigalle. The company thrives to this day, but a decade or so in, he realised he wasn’t on the right path. “I think Pigalle was the first step to expressing ourselves in the fashion world. It wasn’t 100% what I wanted to do, but I thought at the time, maybe my dreams of having a continuation of French fashion codes were a bit passé. But then I realised, no, I need to do things exactly as I want.”

The first Casablanca collection, Spring/Summer ‘19, was positively Calvinist compared to the latter-day vibe. (Now they are more like “doctors who play tennis on mushrooms”, chuckles Tajer.) But it was colourful and irreverent, and in hindsight, exactly what the menswear market needed.

“It certainly came at the right time, an antidote to pure logo culture that was dominating menswear,” says Dean Cook, head of menswear buying at Browns, the first UK store to buy into Casablanca’s debut Spring/Summer ’19 collection. “When streetwear and men’s fashion was all about jersey, suddenly Casablanca rolled in with silks, flamboyant prints, towelling tracksuits and there was a reason to get dressed up again.” Soon after, Casablanca was available in many of the most important fashion boutiques around the world — United Arrows in Japan, Saks in New York City, Ssense online etc. - and it’s been a steady ascent ever since.

New Casablanca ‘products’ come thick and fast. Since 2018, in addition to the seasonal ranges, the brand has launched womenswear, fine leather goods and a skiwear collection, and at the end of last year, launched two limited edition Audemars Piguet watches.

The latest offering, the Spring/Summer ’22 collection, is titled ‘Masao San’ in honour of a Japanese friend of Tajer. And though there are quintessentially Japanese design flourishes the aesthetic is rooted in the work of The Memphis Group, quintessential postmodern interior designers of the 1980s. Marshmallow shapes and undulating hemlines are realised in candy-colour pastels and stark primary colours, resulting in a collection that is at once faintly ridiculous and, somehow, cool. It is the antidote to po-faced fashion, says Tajer.

“It’s easy to ridicule when you are doing colourful stuff,” he explains, “but you take more risks by doing what we do. When you manage to do it right and it looks fun but serious at the same time, it’s the right balance. Then you have something strong. It’s a thin line. But I think this is a real art form; when you play with ‘bad taste’ or fun, but you never fall into it.”

Casablanca, Tajer emplores, is an exercise in glee. Glee for the act of getting dressed, glee for pop culture, glee for the majesty of the world itself. But the fashion industry is famously glee-intolerant. And a joke repeated is a joke diminished. The question for Casablanca, having crashed the staid and rigid world of luxury, is how to capitalise on it.

“My goal is to create a new classic,” he says, leaning back in his chair, steely-eyes visible through big Cartier shades. “I want the brand to exist in a hundred years. So we do everything to give it that basis. Everybody here works with the idea that they are creating something that will be Casablanca vintage in 20 years.”

Tajer dreams of a Casablanca store amongst the greats on Paris’s Rue de la Montaigne, but he is banking on the retail landscape being very different by the time it opens. “I think stores will become 100% experience,” he says. “Almost no-one will buy things from stores, they will be more like amusement parks for adults. You go in and experience the world of Casablanca, it’s the perfect brand for that.”

“I think the [brand’s] success is dependent on his storytelling,” says Forbes fashion and luxury journalist Roxanne Robinson, referring to Tajer’s impressive knack for ‘universe building’. “Some of those brands that made films [as a replacement for pandemic-struck fashion shows] were actually conveying something stronger or better than they ever could on a runway. It gave them another dimension. You saw Casablanca’s ‘Grand Prix’ [A/W’21] film and you thought, ‘I want to be part of that’.

“The sky’s the limit with menswear,” says Robinson. “Charaf hit the market with something immediately recognizable and surrounded by a lot of fun and enthusiasm, and he definitely knows what the ingredients are to grow this brand into something bigger. But you never know.”

There were rumours last year that Tajer would be hired as the artistic director of the LVMH-owned brand Kenzo, but the role eventually went to Nigo, founder of the Japanese label A Bathing Ape. How accurate the rumours were; whether Tajer’s own label will be able to maintain its independence from the luxury conglomerates; if his vision for the brand can be sustained over as many years as the famous legacy labels he measures his success against… all this remains to be seen. For now, it’s enough for him to be able to say, not without justification, that “if you take Casablanca away from the landscape of fashion, there’s going to be something missing.”