If you want no surprises about No Time To Die, then this is your stop. There's going to be spoilers.

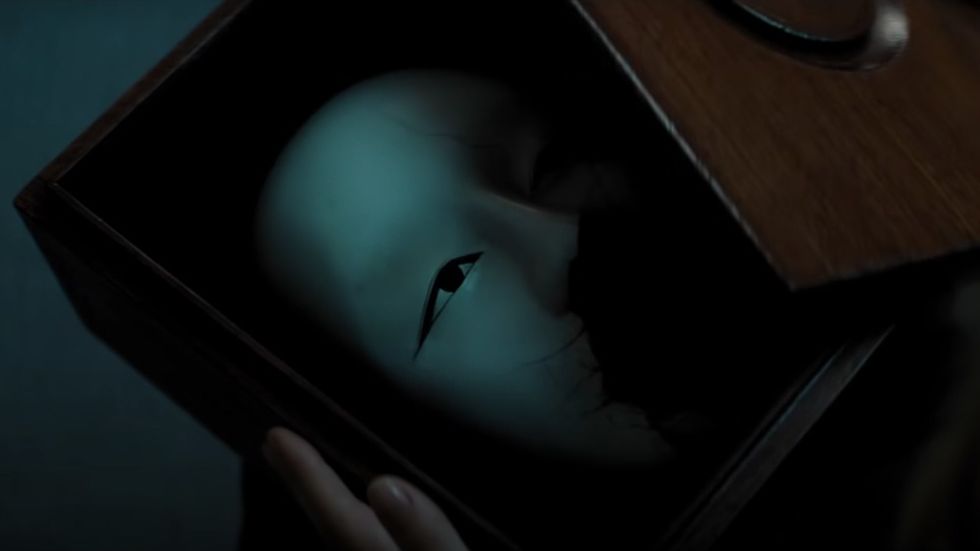

At the beginning of No Time To Die, Léa Seydoux's Madeleine Swann is seen in her youth at her snowcapped, remote childhood home. Her father, not seen, is an assassin for the criminal organisation Spectre. Her mother, a drunk, is barely conscious on the sofa. So inebriated is she that the silent, masked figure leering over her is only spotted too late. She is then riddled with bullets.

As Swann tries to escape, she peers into the same camouflage: a terrifyingly serene Noh mask that is borrowed from Kabuki theatre culture. "[It] is the face of an actor and [they] can never be parted from it," Japanese photographer Toshiro Morita told CNN in 2018. "Humans try to hide their emotions, but masks don't tell you anything."

Therein lies the main thrust of Lyutsifer Safin: the unknown, unhinged villain of No Time To Die, and the man behind the mask. Unnervingly played by Rami Malek, Daniel Craig's final nemesis is perhaps the Bondverse's most evil – and its most enigmatic. In almost every scene (masked or otherwise), his motives are unclear, his emotions well hidden. We don't know much about this Safin. That makes him all the more terrifying.

When No Time To Die's costume designer Suttirat Anne Larlarb sat down with Esquire, it became clear that the Noh mask was an intentional tool to maximise on this fear of the unknown – and to help paint a clearer picture of Safin while obscuring him further. "We knew we wanted to mask his identity for a certain part of the film, and we were looking at different influences," Larlarb says over Zoom. "And we knew we needed to look at different influences as Cary [Joji Fukunaga], our director, gave me a few different adjectives: aggressive, but hidden; serene, but hidden; so many things, but hidden."

Again, the traditional Noh mask seemed to do all of these things, and yet none of them. Lalarb only became aware of its shapeshifting potential when in the R&D phase. "I came across a photo series of a Noh mask that had been lit from behind. First off, it was a very pure and platonic form," she says. "But when it was lit from different angles, the expressionless face changed so much with each shot. It was aggressive, then serene, then terrifying, then caring, and that's something that really spoke to [Fukunaga]. That's what we wanted to start with."

Indeed, Safin only appears in a handful of scenes, but his introduction while wearing the mask sets the temperature of who this villain is. It is also worn for practical reasons in relation to the story. As the sole survivor of a mass dioxin poisoning that sees his entire family murdered, Safin's skin is disfigured; a greyscale map of broken veins and seared bones. And it seems the SFX team did their research. According to the World Health Organisation, exposure to high levels of dioxin "may result in skin lesions, such as chloracne and patchy darkening of the skin, and altered liver function." Though the Bond canon has come under fair and sustained criticism for its demonisation of people with disfigurements, Safin's appearance is, at least, medically accurate.

That makes the mask all the more significant. It maintains anonymity. It allows Safin to hide his past. But it also does so much more than that. The mask also alludes to the emotional tensions within. Several times, Lalarb describes Malek's character as an "architect of the world", someone who is "so self-assured, and always thinking and creating." He is angry and disillusioned, yet fervent and impassioned, calm and short-tempered; an aesthete and a destroyer all at once. These multiple sides are only rarely visible to the audience. But like the Noh mask, we are afforded these views when a new light shines in. Slowly but surely, Safin's mask is peeled away. "People want oblivion and a few of us are born to build it for them," he says towards the film's final act, fully revealing his intentions for both Bond and the world to see. "So here I am, their invisible God, sneaking under their skin."