You know something significant has happened in the world of men’s style when the appointment of a new designer to a venerable Parisian luxury house makes the agenda-setting Today show on BBC Radio 4 — as well as receiving fulsome coverage in every other mainstream news outlet on the planet.

Yesterday’s announcement from Louis Vuitton, confirming that the polymathic American pop culture impresario Pharrell Williams — producer, performer, songwriter, artist, entrepreneur, philanthropist, etc — would take over as the men’s creative director of a company founded in 1854, was both surprising (the rumour began the previous day, but in truth even the best-informed style-watchers were blindsided) and, somehow, inevitable.

It is the culmination of a project, decades in the making, in which Vuitton, the jewel in the crown of LVMH — the luxury and fashion conglomerate owned by the world’s richest man, Bernard Arnault — has reconceived itself from a maker of status symbol luggage and accessories for plutocratic globetrotting jet-setters — a crucial market, but still, believe it or not, relatively niche — into a destination in itself for anyone who can afford it, anywhere in the world, from cool hype kids to suburban adultescents who wish they were cool hype kids, and far, far beyond.

It is also the continuation of the journey of what is known, somewhat misleadingly in 2023, as “streetstyle” — a euphemism for fashion trends pioneered and popularised by the members of hip-hop and hip-hop-adjacent youth subcultures (mostly Black, mostly American) — from homespun outsider ghetto artform, nearly 50 years ago, to established, mainstream commercial leviathan. Just as the sound of hip-hop and R&B has moved from minority concern, in the 1970s and 80s, to the dominant pop-cultural mode of the twenty-first century, so hip-hop style has long broken loose of its strict association with inner city America. Everyone who has ever worn sneakers for anything other than exercising has felt its influence.

Before we get to Pharrell, it might be necessary to go back to those early days and the innovations of the African American designer and entrepreneur Daniel Day, aka Dapper Dan, who long before LVMH or anyone else thought to hire an icon of Black American cool to give it kudos — and concomitant sales — was working in the other direction, taking the logos and codes of the luxury European houses and repurposing them for a clientele of ghetto aristos: gangsters, boxers, and hip-hop pioneers including LL Cool J, Eric B and Rakim and Salt N Pepa.

For a decade from 1982, on 125th street in Harlem, stood Dapper Dan’s Boutique. Here, a shopper could discover a kind of counterfeit couture: garments made to order, in leather and fur and exotic skins, embossed with the logos of Gucci, Fendi and Louis Vuitton, using a silkscreen technique of Day’s own invention. Like the early New York DJs who sampled classic rock and soul tracks for rappers to extemporize over, Dapper Dan borrowed the branding of the established European houses, who at the time declined to sell to him, and reworked them. In 1992 he was shut down. By the end of that decade, far from excluding Black America, even from their stores, luxury brands had begun to court rappers and sports stars as consumers, as well as potent marketeers for their products. It took a while longer for the fashion establishment to see the stars of hip-hop as potential collaborators and, now, creative leaders.

“Fashion is just a vehicle,” the effervescent Dapper Dan told me, when I interviewed him at his shop in Harlem a few years ago. “It’s an instrument to express something much deeper, and to hopefully affect change.”

At Louis Vuitton, which has been among the heritage brands that have helped lead the way in this story, the key players, Bernard Arnault aside, have been a trio of designers: Marc Jacobs, Kim Jones and Virgil Abloh.

First, from New York in the 1990s, came Jacobs. He famously applied the ethos of downtown Manhattan to the Paris catwalk — most memorably, and remuneratively, in 2000, when he invited the grafitti artist Stephen Sprouse to paint the Vuitton name over a collection of bags that remain totemic in the story of the luxury industry’s infatuation with the codes of streetstyle.

More directly inspirational on the Williams appointment are his two predecessors in the role of men’s creative director: from London, Kim Jones, the clairvoyant British designer now turning heads and emptying pockets worldwide at Vuitton’s stablemate, Dior, as well as designing the women’s collections for Fendi; and, from Chicago, Jones’s replacement, Virgil Abloh, who died in 2021, at the age of just 41, after three electrifying years at Vuitton.

Jones’s period at Vuitton, between 2011 and 2018, was significant for multiple reasons. It was he, more than anyone, who fused the styles and aesthetics of youth culture with the fabrics, techniques, exquisite detailing and sensibilities of couture. Many of Jones’s designs are clearly influenced by sportswear, and by hip-hop and club culture, among many other things. But anyone who has worn a Jones creation knows that the quality of the garments is far removed from those made by the high street brands. “I hate when people call my stuff streetstyle,” Jones told me, in 2020. “It doesn’t mean anything. It’s lazy.”

It was Jones, nevertheless, who first filled the front rows of Vuitton men’s shows with pop stars, rappers, athletes and assorted representatives of “the culture”, the catch-all term for the Black and minority-originated and hip-hop-associated aesthetic. Jones, too, pioneered collaborations with brands traditionally outside the world of high fashion and luxury, notably the New York skate brand, Supreme.

As well as an accomplished showman and a sharp business brain, Jones is a fashion designer in the traditional sense. An art school graduate who went on to study for a MA in men’s fashion at Central Saint Martins, he can cut a pattern with the best of them. Virgil Abloh, too, had an academic background, only his was in civil engineering and then architecture. A DJ, product designer, graphic designer, artist and entrepreneur, before joining Vuitton he launched his own labels, first Pyrex Vision and then Off-White, and he had a long association with Kanye West, with whom he interned at Fendi, in 2009. The fact that he was a Black designer, from within the culture, working at a European luxury house, was significant. Jones, his predecessor, was clear on that. “Virgil at Vuitton is important,” he told me.

Abloh’s shows and collections for Vuitton were a sensation, with a global reach equal to a major sporting event or a showbiz awards ceremony. Catwalk shows were now Barnum-style entertainment events, with the production values of arena pop concerts — which they increasingly resemble — designed for and disseminated on social media.

The creative directors of these events need to understand more than how to cut cloth. And that’s the thing those outside fashion perhaps find harder to understand — some of the commentary on Pharrell’s appointment reflects this — when they hear that someone more closely associated with pop stardom than fashion design can be appointed to take charge of menswear at a brand like Louis Vuitton.

You don’t have to sit exams to qualify as a fashion designer. What you need, above all, is taste. An aesthetic vision for what the products and the marketing of them should look and feel like. Plus the ability to attract a loyal following of customers willing to pay for a piece of your work. On that score, Virgil Abloh was always going to be a hard act to follow. If anyone can do it, one senses that Pharrell Williams can.

Williams, who will be 50 in April, has been steeped in the culture since childhood. I interviewed him for a magazine profile, in 2007. At that time he was already world famous, and phenomenally successful, as the producer and performer behind the Neptunes, N*E*R*D* and a catalogue of hits for stars including Justin Timberlake, Britney Spears, Jay Z, Snoop Dogg and many more. At one stage, in 2003, a staggering one in five records played on British radio had been given Williams’ platinum touch; the figure in America was even higher.

But our conversation, even then, was as much about style and aesthetics — fashion, design — as it was about music.

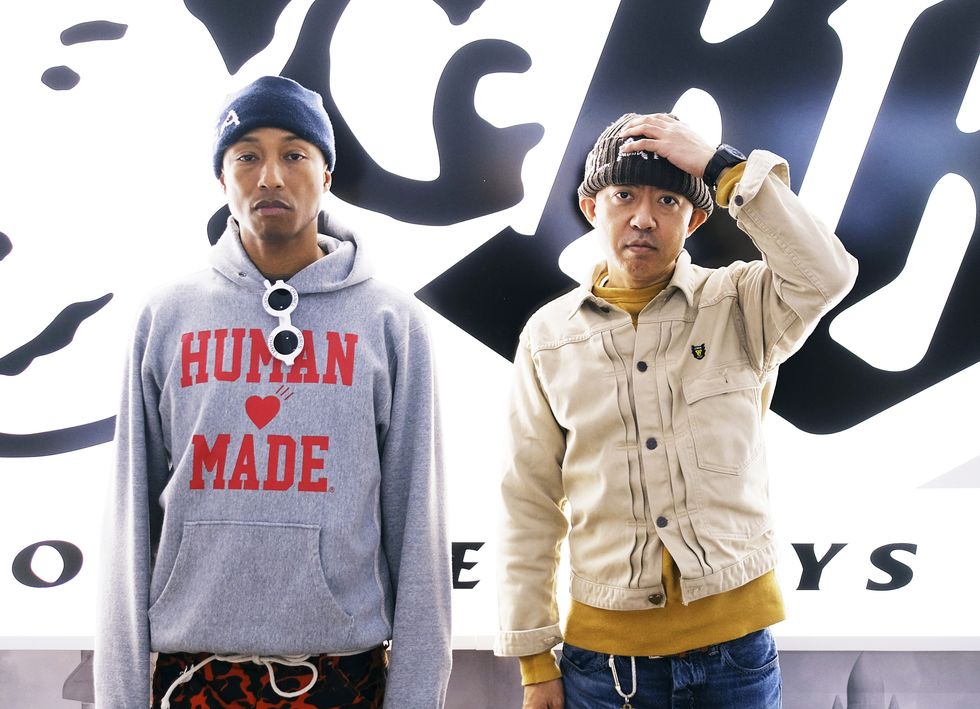

Then as now, Williams had two fashion labels of his own, Billionaire Boys Club and Ice Cream. Designed and manufactured in collaboration with Nigo, the Japanese designer and entrepreneur behind A Bathing Ape (now also the designer at the Paris label, Kenzo), Billionaire Boys Club and Ice Cream are not vanity projects: Williams told me he is intimately involved in selecting fabrics, choosing cuts and shapes, sketching designs. Billionaire Boys Club he characterised as “like Willy Wonka took over the house of Ralph Lauren” while Ice Cream is “more like the skate mentality but with couture materials.” To say, from the vantage point of 2023, that this was prescient, is to undersell things considerably. (Not something a fashion entrepreneur would countenance.)

What we didn’t talk about much about was his personal life, because Williams in person, for all the undeniable glamour of his existence, is a deeply unassuming man. He had only agreed to our meeting, he conceded, because “my record company goes fucking apeshit on me if I don’t do interviews.”

He told me he doesn’t much like talking about himself with anyone, even close friends and family. He regards it, somewhat refreshingly, as showing off.

“I like my music to speak for me,” he said. “Self-glorification is a big turn-off for me. Sitting around listening to somebody talking about themselves all damn day long… why? Yo! Go and live in a fucking mirrored house.”

When I complimented him on his success, he actually flinched: “Credit is to be given not to be taken.”

Our meeting took place at a recording studio in a flaking art deco building on Collins Avenue, Miami Beach’s slightly forlorn main drag. This was hardly the bauble-stuffed pleasure-dome of a contemporary Phil Spector. A ghastly orange, green and purple wall panelling was offset by a thick, palm tree emblazoned carpet. Plugs were kept in sockets with Sellotape, and the walls were decorated with signed prints of Seventies and Eighties album cover artwork (Supertramp, Rush). Williams was jammed into a small room at the back of the building, surrounded by equipment: keyboards, a mixing desk, amps, speakers, serpentine wires.

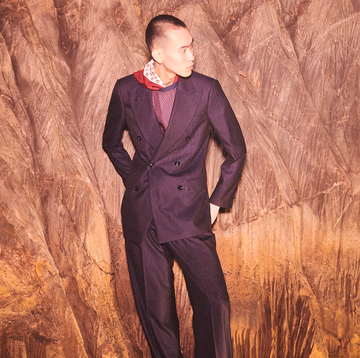

My notes from the time record what today we would call his ‘fit: dark denim jeans from his most recent collection for Billionaire Boys Club, a white T-shirt of the same provenance, featuring the label’s distinctive astronaut logo. (Williams is a sci-fi nut.) On his feet: trainers from A Bathing Ape. He had a thin gold chain around his neck, set with diamonds, and a diamond earring in each lobe. Discarded on an amp at his side were a yellow-diamond-studded Casio G-Shock watch, and an enormous gold and diamond ring. Attached to his diamond emblazoned N*E*R*D* belt was a diamond encrusted carabiner. His arms and the back of his neck were decorated with tattoos of pneumatic angels.

On the table to his left: a half-full jar of Chewits, a vase of fading daffodils and a turquoise towelling Hermes sunhat.

He was disdainful, when we spoke, of the homogeneity of much pop music. He felt the same way about fashion. “The minute I feel I’ve been boxed in,” he said, “I change. Trucker hats? Don’t do that any more. Blazers? Don’t do that any more. Big chains? Don’t do that any more…”

Williams ascribed much of his success to his desire to always go against the grain. “You always got to switch it up,” he said. “You can’t be afraid to do what’s right. I like for things to be striking. You never see me doing what everybody else does. I like to be a sore thumb.”

As with his music, Williams characterised the eclecticism of his style to his diverse background. He described his hometown, Virginia Beach, as “Normalville, not nothing out of the ordinary.” Yet his childhood was extraordinary, at least in the sense that at age eight he was extracted from the projects by his parents and moved to “the modest suburbs”, where he was a rare Black pupil in an overwhelmingly white school. As a result, Williams’ consciousness, as well as his aesthetic, was forged in an unusually cross-cultural environment.

“I was always weird,” he told me. “Not super-weird, just different. I always dressed different. To the media back then, a white kid was white and a Black kid was Black. We dressed different, talked different. But to me, music was always multicultural – everybody liked Michael Jackson, everybody liked Madonna and Prince.”

Williams’ conversation was peppered with pop-cultural references. During our afternoon together he mentioned Morrissey, The Cosby Show, Wham!, the Dead Kennedys, Danny Glover, Doug E Fresh and the Smurfs, and shared enthusiasms for the Anglo-French knob twiddlers Stereolab (“crazy shit”) and the stroppy Rage Against The Machine frontman Zack de la Rocha (“genius”).

It’s these things, he said, that stimulate and inspire him, along with his faith – he’s a committed Christian (“although I still curse and fornicate”) – and an interest in the cosmic. N*E*R*D* stood for No-one Ever Really Dies — a clue, perhaps, to the beliefs of the band’s leading member.

What keeps him going, he said, is discipline and a love of his work. “I don’t have any structure to my life,” he said. “My life ain’t planned out. Most people are in a financial bracket that dictates what they gotta do. They got a mortgage, car payments. Once you make a certain amount of money it’s like, ‘What’s next?’ I gotta wake up every day and go with the gut.”

In the years since that interview, Williams’ prominence has only grown, in entertainment and in fashion. His appointment to the position at Louis Vuitton was preceded by a number of collaborations with the brand. He was the first ever male ambassador for Chanel. He has designed a collection for the jeweller, Tiffany & Co. He has a longstanding partnership with Adidas and his own skincare and wellness brand, Humanrace. He has also won 13 Grammys, been nominated for Oscars, opened a hotel, put on a music festival, and fathered four kids.

His first show for Louis Vuitton will take place in Paris, in June. I’m going out on a limb here, I know, but I think it might be quite the hot ticket.

As the sun went down over Miami Beach way back when, Williams and I moved from the studio out to the front porch, where we ate cashew nuts and watched the senior citizens in velour tracksuits go by. Williams seemed relaxed and content. I asked him if he could possibly be as unfazed by his astonishing success as he seemed?

“Half the time I’m in the Twilight Zone,” he said. “I’m like, ‘Where am I? What the fuck is going on?’ Like, whatever you do, don’t pinch me. I might wake up.”