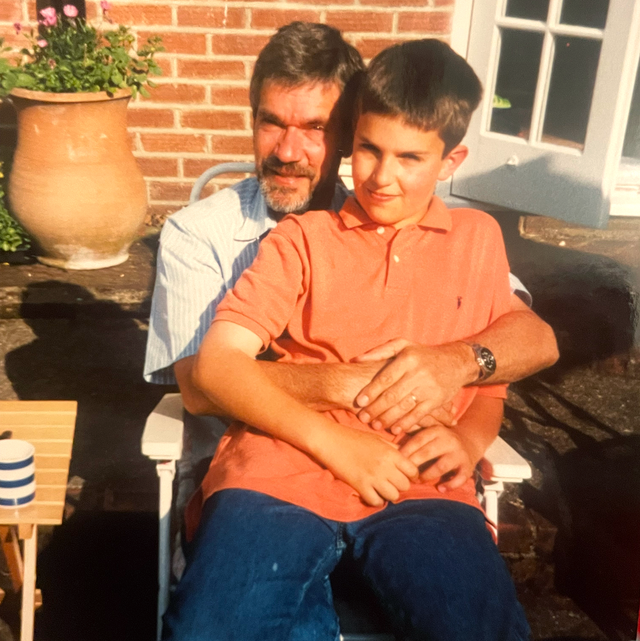

I woke to the sound of mum pushing at my bedroom door. The clock on my bedside table read 8.05am. Far too early to be roused on a Saturday.

“MUUUM. Can you knock, please?” A thimble of Tropicana preceded her. Mum saved her smallest glasses for servings of orange juice. “And WHY are you waking me up so early?”

“Sorry, darling,” she said, not sounding sorry at all, but waving a Marks & Spencer carrier bag as a peace offering. She sat on the edge of my bed. “I thought you’d like to wear this to go fishing with Dad today.”

“What is it?” My interest was piqued by the prospect of a gift, though my stomach fell at

the reminder of the trip. A few weeks before, I’d overheard Dad tell Mum that he thought

he and I needed to bond. “He doesn’t like any other blahdy sports, Jane, so maybe he’ll like fishing.” This was to be his last-ditch attempt at filial galvanisation.

“Open it and see.”

Out of the mouth of the bag I pulled a blue, white and grey plaid shirt jacket. Cut from

a heavy fleece fabric, it had two bellows pockets, in line with each pectoral, and it was filled with a thin layer of down. Inside, the lining was made from quilted black nylon, which, Mum told me proudly, meant it was waterproof. The stiff newness of the thing coupled with its aesthetically pleasing practicality spoke to me in volumes and I wanted to wear it immediately.

“Try it on for me, then.”

I jumped out of bed, not yet deep enough into puberty, at 12 years old, to be concerned about wearing boxer shorts in front of my mum, and pulled the jacket on; the nylon of the lining felt cold against my skin. I looked in the mirror and took myself in. I resembled, I thought, a young Grizzly Adams, or the megalosaurus patriarch in Jim Henson’s early 1990s puppet sitcom, Dinosaurs. I felt masculine. Impressive in my broad-shouldered, plain-coated blokeishness.

“Come and sit down, darling,” said Mum, pausing as I arranged myself on the bed. “You know you can talk to me about anything, don’t you?”

“Ummm, yes?” I said, feeling my face flush.

“Well, just remember that. Now get up, you’re going to be late for your father. And we wouldn’t want that now, would we?” She smiled wryly.

In our upstairs loo was a tall pine dresser where old magazines were sent to die. It housed dozens of dog-eared copies of Hello! and OK!, retired once they’d served their time on the

conservatory coffee table. The dresser enabled direct and convenient access to the stack while you were doing your business, which was useful as my favourite issue — a worn-out copy of OK! featuring a ‘world exclusive’ shoot with the Beckhams at home in Hertfordshire — had recently been relegated upstairs. David had shaved his head, he had two giant diamonds plugging the lobes of his ears and he was pictured doing odd jobs around his house, which looked like an engorged version of one of those show kitchens advertised on telly at Christmas time.

Every time I went to the loo, sometimes because I actually needed to, I would thumb through that issue. Pausing briefly on one particular shot of David wearing a yellow T-shirt and a boyish side grin, I would swiftly make my way to the back where there was a featurette on the boy band 5ive. One picture of Abz had quickly become my favourite to spend time with. (Richard Abidin Breen, in all his tanned and tattooed bad-boy glory, was my favourite 5ive member, closely followed by Scott; I always thought Ritchie looked a bit like my Aunty Rozy.) In the photo, Abz wore an oversized, unbuttoned denim vest with nothing beneath it, torso fully oiled — his rolling abdominals winking at me from beneath the varnish of the page — and he had his tattoos on display. My favourite was the one on his right wrist, which spelled out the word “DREAMER” in Old English lettering. The “R” peeking out from beneath a cuff made my tummy go funny.

On the day of the fishing trip, I’d hoped to have some time alone with the magazine before Dad and I set off. Just as I had landed on that picture of Abz, my stomach flipping like I’d gone over a lumpy hill in a hatchback, there was a bang on the door and I shoved the magazine back into its designated position, behind an issue I rarely looked at, Dame Shirley Bassey having less appeal than Becks and Abz.

“Dao, are you in there?”

“Yes, sorry, Dad. Give me a second.”

I knew that Dad wouldn’t go away and wait for me to finish. Instead he’d stand jiggling outside the door in his pants until I let him in, so I pulled up my boxer shorts, willing away whichever lustful stirrings had occurred beneath the waistband, shimmied up my pyjama bottoms and unlocked the door.

“What were you doing in there?” He eyed me suspiciously.

“Nothing,” I lied, as I inched around him to go into the bathroom, which was across the hall. “I’ve got a bit of a funny tummy,” I lied again, as I splashed some water onto my hands, pretending to wash them.

“What colour was it?” asked Dad, suddenly forgetting how much he needed a wee. “Was it watery or more like a custard consistency?”

Dad loved talking about poo. He said it was because he was Dutch; Mum said it was because he was kinky.

“It was fine, Dad, just a bit gurgly,” I mumbled as I went back into my room, shutting the door on the conversation, eager for a few minutes alone before our odyssey to the Thames. Making doubly sure the door was firmly closed, I went to the cupboard at the back wall and retrieved my favourite Christmas gift from that year. Mum, who had obviously twigged my new-found craving for privacy, had given me a miniature safe, designed to look like an old book. Made from burgundy plastic that had been roughed up and gilded, it looked as discreet on my shelf as a drag queen at an accounting convention and it only had room enough for a Coke can inside, but I couldn’t have been more pleased with it.

It had taken a while to find a use for it but eventually I’d started using it as a receptacle for

cut-out pictures of men in various stages of undress.

Confident that Dad was still in the loo, I unlocked the “book” to reveal the pages concealed within. Amongst them was the one of Paul Cattermole from S Club 7, wearing naught but a black vest and a grin, and one of Gianni from EastEnders glowering furiously in a black leather jacket and a Nehru collar suit. He looked like a sexy version of one of the priests at my Catholic secondary school.

I thumbed through the pictures, feeling both excited and unsure about why I was so preoccupied with looking at them. I veered between a surging sensation of exhilaration — as though a high-pressure hosepipe had been let off in my stomach — and flat-out embarrassment, attracted to the men in the shots but somehow repelled by them, too. One by one, I laid the pictures out on my bedspread before removing a sheet of white plastic, which was embedded into the base cavity of the book, concealing another space beneath it. Inside sat a folded-up piece of white A4 printer paper, the creases as clearly defined as the reticulate veins on a leaf, embedded deep from repeated folding and unfolding. I opened the page to reveal an image of a muscle-bound man, all lubed-up lumps and bumps. He was leaning on a hay bale with a soft smirk on his face, a kiss curl breaking free from the rest of his hair, which looked like it had been moulded from plastic. In his right hand was a penis so big you’d have been forgiven for thinking it was an off-colour cucumber.

My stomach flipped again at the exact moment the toilet next door let out a low gurgle. As the lock scraped open, I quickly folded the piece of paper as carefully as I could and secreted it into the depths of the book, clumsily fitting all the composite parts back into place before shoving it onto the shelf without locking it. My heart thwacked against my ribcage as I heard a soft knock on my door. “Shall I do a fry up for brunch, Dao?” asked Dad. Mercifully, he was much better at not barging in than Mum was.

“Yes, please!” I shouted, silently willing him not to turn the worn brass handle.

“OK then, see you downstairs in a minute.” A pause. “Fancy some sausages too?”

I took a sharp lungful of breath. Was he making a joke? “Yes, please! Crispy, please!”

On the way to Teddington Lock, Dad pointed out some of the more expensive cars on the road, naming the make and model with an impressed upward inflection: “There’s a Mercedes SLK!” He would then glance over, expecting me to raise my eyebrows approvingly; it was only after he’d looked back at the road that I could resume gazing out of the window at the hedgerows flying by.

When we arrived, the sky was moody and it was cold, even with my new jacket fully done up. I was consoled by the fact that I looked the part — the bruised blues and greys interwoven through the check of the jacket perfectly matched the slate of the clouds above and the deep indigo of the sluggish river below. I looked as though I belonged there, even if I didn’t feel like I did. There was something comforting in that.

“Come on, Teo, let’s go over here,” said Dad briskly, as he gathered our kit into his arms. He was wearing his favourite Aviator shades despite the lack of light — my dad was a commercial pilot — and he had wellies on even though the area around the lock was paved in broken slabs of stone and gravel.

We walked for a while, crunching down the path as the autumn sun pushed weakly through the quilt of clouds. The wind was sharp against my cheeks. Eventually we stopped at the edge of a stagnant-looking bit of water. There was another pair of fishermen a few spots away and the leader, an older man with a beard bigger than my dad’s, looked both furious and bemused by our presence.

“It doesn’t look like there’s much in there, Dad,” I said.

“It’ll be fine.” He paused, looking more sceptical than he sounded. He glanced over at the other fishermen, who had retreated into the shelter of their tent. I thought better of asking Dad why we didn’t have a shelter of our own. “Here’s your rod,” he said.

Dad handed the line to me, knowing full well I wouldn’t know how to string it myself, and together we went about preparing it for the business at hand. After attaching the reel with his big square hands, he gently guided mine as we threaded the clear line up through the shaft of the rod. Job done, Dad attached the lure as he was worried about me hurting myself on it. A glistening feather the colour of blue glass, the evil-looking curve of steel glinted in the gloaming as Dad took out an old tobacco tin from his fishing bag, which was really an old plastic toolbox he’d repurposed for the trip.

“What’s in there, Dad?” I was anxious for him not to start smoking.

“Maggots,” he said proudly, smiling at the screwed-up face I made as he opened the tin and showed me the mass of white larvae within. With surprising delicacy, Dad removed a single maggot from the receptacle and quickly skewered it onto the hook, the fleshy pellet wriggling helplessly against its sharp metal edges. I couldn’t help but feel sorry for the maggot as it jolted and jigged, not least because it brought to mind an incident that had happened a few months before our trip, in which I had played the role of the squirming larva.

Dad had recently replaced our old Amstrad computer with a brand-new PC, which took pride of place in the downstairs study. It consisted of two giant grey boxes — a screen and a processor — and Dad had even bought a new desk from Ikea to house it. Finished with specific slots for the keyboard, the mouse and the many bootleg CD-roms he’d purchased on trips to Hong Kong — including my personal favourite, the Encarta encyclopaedia — it looked, I thought, like the control desk at Chernobyl (which I’d seen many times illustrated on the aforementioned programme), albeit clad in pine-effect laminate.

To access the internet on Dad’s new toy was a task. The modem, which he’d installed at the same time as the computer had been winched in, was treated with a certain mad reverence (“You haven’t touched the modem, have you, Dao? You must never touch the modem”) and it would churn, grind, whistle and squeak its way through its connectivity mating call, meaning you’d need to wait at least three or four minutes for the homepage to appear. Perhaps more importantly, however, it also told everyone in the house, in squealing tones, that you were diving head-first into the brave new territory of the world wide web.

As far as my dad knew, the main reason I wanted to go online was to use MSN Messenger. Each evening, my sister Romy and I were permitted one hour of chatting, her at 5 p.m., me at 6 p.m., during which we would sit at the screen typing manically to the friends we’d last seen at school just a few hours before. The conversations tended to go something like this:

Ilovewomen87: Hi! Text back

Lozwozere: Hi Tb

Ilovewomen87: brb, dinner

Lozwozere: k

Ilovewomen87: Back! TB

Lozwozere has logged out of MSN Messenger

To use MSN Messenger, I was required to create an email address, so instead of picking something simple — my name@hotmail.co.uk, for instance — I’d opted for ilovewomen87@

hotmail.com. Perhaps it was a bid to conceal my burgeoning sexual desires; perhaps it was a way of making me seem more masculine than I was. Suffice to say, it didn’t achieve either goal.

Johndinage4: Hi Gayo

Ilovewomen87: Hello

Johndinage4: Why is your name Ilovewomen, Gayo?

Ilovewomen87: I dunno, I love Geri…

Johndinage4: GAYO, GAYO, van den POOPER

Ilovewomen87 has logged out of MSN Messenger

The real reason I wanted to use the internet was to access porn. Luckily for me, my mum had just started doing an Open University degree in English Literature, which meant she was out at the library several evenings a week. On those days, when they fortuitously coincided with Dad being away on a trip, Romy would sometimes be sent to her friend Robin’s house to have tea and for the odd afternoon I would be left at home on my own for a few sweet, solitary hours when I would have the computer all to myself.

On such a day, the excitement would build: the second I got home from school, having caught the bus as early as possible, I’d careen through the front door and into the study to power the thing up. During the wait, I would have time to double-check both upstairs and the garden, in case Dad had secretly returned from a trip without revealing himself. Only once I was absolutely sure that the coast was clear would I then start up the modem, all the while keeping a furtive eye out. The entrance to the study was finished with three plate-glass panes, which faced directly onto the front door, around four metres away. On the left of the door was a window that looked out onto the driveway and allowed me to see if any cars were pulling up, so long as I kept my neck craned and my eyes peeled at all times.

Once in position, like a lusty teenage contortionist, I would type into the AOL search bar — this was in the days before Google — ‘Gay Men Penis’. Truth was, it had taken me a long while to build up the courage to type the words. I had tried “Gay Men Willies” a few times before and the results had been nearly as tame as the images I’d sourced from my mum’s magazines, so I knew I needed to up the ante. The problem was that the more explicit the words became, the more I grew aware I was on the hunt for something that was — in the eyes of my parents, my family, the world — wrong. Simply tapping the letters into the keyboard was enough to induce a flash of nausea at the base of my oesophagus, and I would flick my eyes toward the door with each letter I struck. P — flick — E — flick — N — flick — I — double flick — and S.

Slowly, like a Roman blind being lifted by a half-awake octogenarian, the white space of the window revealed countless tiny pink- and brown-hued thumbnails of men holding their own penises, men grabbing other men’s penises and men putting their penises in places that, to teenage me, looked very uncomfortable indeed.

On the day of the incident — which still makes me squirm, maggot-like, every time I think about it — I scanned the page, searching for a thumbnail that spoke to me. Eventually I alighted on one of a man that — if I squinted — looked a bit like Abz. He had sallow skin, dark features and tattoos up and down his arms. His eyes were bright blue and his manhood was almost cartoonish in its girth.

Arching my neck round the edge of the door, I did a quick check that no one was coming, kept my ear out for the crunch of driveway gravel against the aircraft-like hum of the processor fan, and clicked on the picture. My mouth became increasingly dry as I waited — one second, two seconds, three seconds, four — before finally the image revealed itself. Quickly, I turned on the gigantic printer and clicked ‘print page’.

WHHIRRR, CLLLICCK, GGRHRHRHHHG. The enormous electronic box crackled into action and slowly started to print out my chosen picture, line by line. I couldn’t take my eyes off the mouth of the machine, watching the boy — who must have been a good nine years older than me — gradually materialise in ribbons of ink. Just as the cartridge reached his navel, the printer paused in its activity, as if taking a breath, and I heard from the corner of my ear the distinct crack of rubber on gravel as my mum’s car pulled up outside.

In a flash, I grabbed the piece of paper straight from the printer, making the thing scream like a puppy whose paw had been stepped on, before stuffing it into my blazer pocket, quickly exiting the screen, switching the giant grey box off at the plug in a bid to muffle its moans, and opening MSN Messenger, which I’d had poised, ready and waiting, at the bottom of the screen.

“Yoohoo!” called Mum to no one in particular as she came through with her arms full of lever-arch folders. She pushed her way into the study and looked down at me with a mix of affection and irritation. “What are you doing in here, darling? I’ve got so much work to do. I need the computer tonight.”

Obediently I shut MSN Messenger and vacated the room without a word, praying silently that she wouldn’t notice the great lump of scrunched printer paper protruding beneath the fabric of my blazer or the bright flush of pink beneath my beading skin.

Safely ensconced in my room, I opened my book and hid the half-printed picture inside, locked it back up and returned it to the shelf, before shedding my uniform and heading downstairs to watch The Simpsons.

Dad came home at around eight that night. He was tired — he’d just finished a day flight from Shanghai — and he wanted to check his emails. “They’ve changed my roster without telling me, Jane; they want me to fly to New York the day after tomorrow,” he said, looking enraged. “I’m blahddy knackered!” He stomped out the room.

The familiar chirrup of the modem made the hair on my neck and arms stood up and I felt my eyes widen.

“What’s the matter, darling?” asked Mum.

“Nothing,” I lied.

“JANE,” I heard Dad shout. He sounded equal parts perplexed and angry. Slightly scared, too. “Come in here!”

“What is it, Jan?” Her chair scraped as she padded out from the parquet of the kitchen and onto the carpet of the study.

“Oh my GOD!” she shouted, stifling a laugh. “Is that a… willy?!”

In my haste that afternoon I had forgotten the printer had a habit of printing things that had been cancelled halfway through when it eventually came back to life.

I brushed my teeth quickly so I wouldn’t have to encounter my parents again that night and barricaded myself in my bedroom: lying on top of the bedspread with my clothes still on, attempting to put the image of my dad waving around a half-printed picture of a penis by reading Harry Potter. After what seemed like hours of failing to take in a word of the same two pages of The Chamber of Secrets, I fell asleep.

When I woke early in the morning, I noticed that someone had pulled the cover up over my legs and taken off my socks.

Back at the river, the maggot eventually stopped squirming on the hook and I looked up at Dad to see if he’d made the same connection between me and the beleaguered baby fly, but he was staring out at the water intently, looking for a spot suitable to cast the poor creature to its final resting place. I shivered slightly as the hook broke the oily surface.

After a few hours without even a hint of a jerk on either of our lines, Dad suggested we go back to the car and eat our sandwiches. It was getting dark and I was starting to lose the feeling in my fingers, so I didn’t need telling twice. With a rod-based dexterity I had hitherto failed to demonstrate, I reeled the line back in, helped Dad dismantle it and made for the car at pace.

We sat chewing in silence until eventually Dad, who had started to fidget uncomfortably, turned to me and said in one breath, “You know, Dao, it’s OK to think about sex, but it’s not good to look at dose kind of pictures on the internet.”

I froze, my mouth hanging open mid-mastication. We had not spoken about the printer debacle since it happened, and I was hoping against hope that he had forgotten about it. Or, at least, that we would never talk about it again, forever and ever amen. I didn’t know what to say, so I didn’t say anything.

“Sex is a part of life,” continued Dad, looking down at the steering wheel. “It’s how we made you, for goodness sake!” His awkward smile quickly turned back to a frown.

“The most important thing is, though, you have to respect people. You have to respect women.”

Women?

“It’s the most important thing, and those pictures on the internet are not respectful. You have a mum and a sister and you need to think about them.”

Why was he talking about Mum and Romy? I was looking at penises! Hundreds (and hundreds) of penises.

“Anyway, I’ve put a lock on the computer now so you can only go on the internet when you

have my permission,” he said, eyes fixed on the steering wheel, apparently fascinated by the tessellating blue-and-white triangles of the BMW logo. “I don’t want you looking at those pictures again,” he said firmly.

My stomach plummeted. No matter how embarrassed I was by those photos, they were also a lifeline: a pixel-and-paper route out of my heteronormative suburban life. These were the days before hook-up apps, Queer as Folk had yet to air on TV and Mum and Dad still laughed when Dale Winton came on the screen. Without access to this physical semblance of my desire — a sexual future I did not yet fully understand was eventually to be mine — I felt unsure what I would do.

The fisherman jacket suddenly felt more than a little silly. The weight of testosterone-infused armour it had provided me with dissipated and I felt like a daft kid playing at being a man. I was desperate to take it off, and I threw it onto the back seat with the rods.

“Can we go home, Dad?” I asked quietly. “I’m tired.”

Dad looked at me then, his eyes slightly drooped as he pulled one hand through his thick thatch of silver-speckled black hair, screwing up the tin foil that had contained his sandwiches with the other.

“Um, yes, OK,” he said. “Your mum will be getting worried.” ○

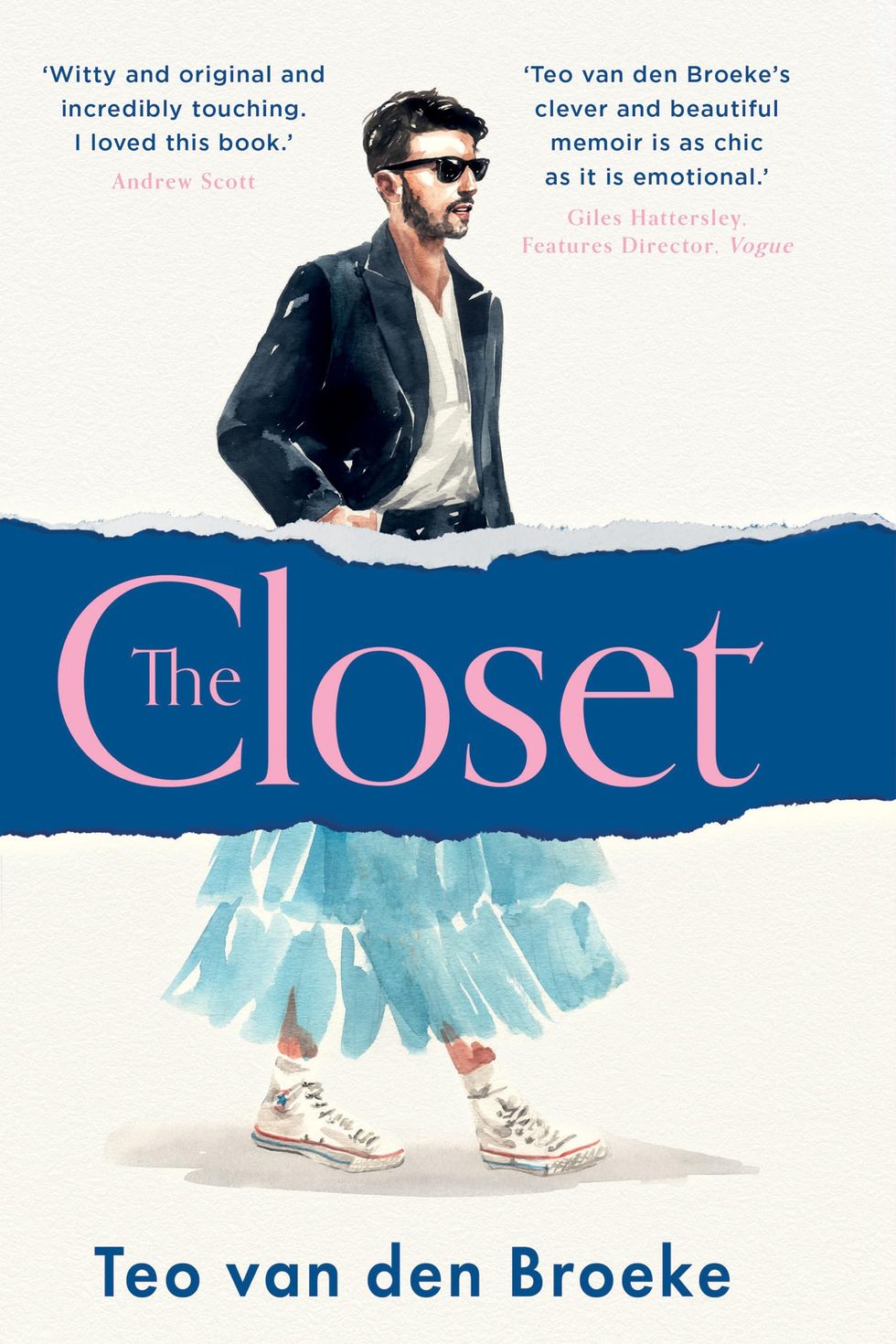

This is an edited extract from ‘The Closet: A Coming of Age Story of the Clothes That Made Me’, by Teo van den Broeke, which will be published on 28 September by HQ, HarperCollins