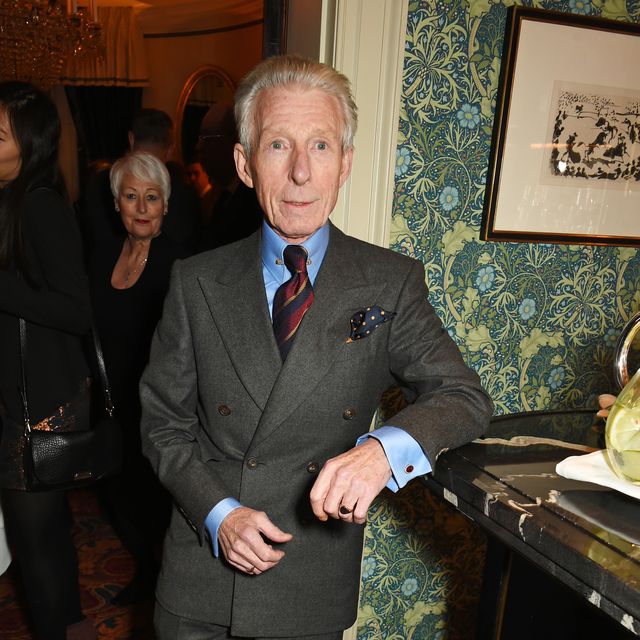

In a seismic loss to British fashion and craftsmanship, Edward Sexton has died, aged 80. The Dagenham-born master tailor rose to prominence in the Sixties and Seventies alongside collaborator Tommy Nutter, dressing such luminaries as Mick Jagger, Elton John and the Beatles (all three suits on the cover of Abbey Road) and redefining British tailoring heritage in the process.

Toward the end of 2022, Sexton opened a new store on Savile Row, the spiritual home of British (nay, global?) tailoring. The monocultural power of the street has waned over recent years, partly because men (not exclusively, but mainly) don’t wear suits as much as they used to, and partly because the notion of luxury has evolved to be more concerned with brand and exclusivity than craftsmanship and quality. But Sexton’s return offered a glimmer of hope. “In 2022, we’ve stuck to the business's values and returned to Savile Row at a time when the world is changing and people are wearing fewer suits,” Sexton told Forbes last year. “We’ve never diluted the brand's look, and now we’re standing up and saying we’re here, and this is what we believe in.”

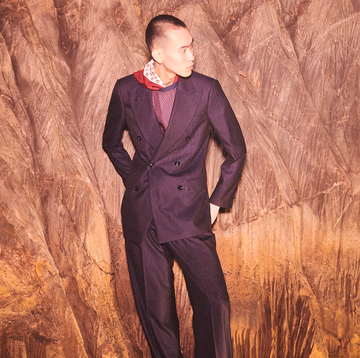

That look, originally known as a ‘Nutter Suit’, was something alien to British tradition when it arrived. As opposed to the usual, conservative, straight-up-and-down block – the kind of thing a politician or bank manager might wear, and very much not a piece of ‘fashion’ – it featured a super narrow waist and broad shoulders, with fat peak lapels that almost covered the chest, and trousers cut with floaty volume that kicked out at the hem. And always in a fabric chosen to catch the eye, rather than avoid it. Loud, flattering, and cut for the dance floor.

When Nutters opened in 1969, it was the first new tailoring house on the Row for over a century. It made a visit to the tailor’s shop fun, and it even dressed women. There have been more new places since, but none so iconoclastic, or interwoven with pop culture, or influential. The “New Bespoke Movement” of the Nineties, spearheaded by young tailors including Timothy Everest, Richard James and Ozwald Boateng, might never have happened without Nutter and Sexton. And the silhouette is evident in the work of designers from Ralph Lauren to Phoebe Philo.

Embedded in the party scene he so admirably dressed, Tommy Nutter’s wild lifestyle was famous, and by 1976, Sexton had bought-out his business partner to become managing director. Soon, he would open a shop in his own name, and by the early 90s, left Savile Row for Knightsbridge. The silhouette remained, available by appointment only and bolstered by accessories to offer a complete Sexton look, but evolved to allow for changing tastes. Fewer garish patterns, but all of the attitude.

When Sexton finally returned to the Row last year, more than half a century after he first arrived, his aesthetic was once again at odds with tailoring’s status quo, but in line with wider trends. Visit Canary Wharf – one of the last hold-outs of suit-wearing Britain – and you’ll see men in short, shiny jackets with skinny lapels and trousers cut low on the waist and slim in the leg. The look is not a celebration of personal style, but instead a sad indictment of what the suit has become: a limp attempt at formality in the face of an ever more casual world.

But there are still a few very good, stylistically interesting tailoring houses in the UK. The growth of Drake’s, for example, shows that a suit maker can espouse not just quality or luxury, but a lifestyle. And away from the boardroom, weird suits are cool again – especially those that are weird in a Seventies way. This year’s award season was awash with flares trousers, narrow waists and, sharp, wall-chipping shoulders. Paul Mescal, for example, has become one of the most stylish men in the world based solely on a run of very good, Sexton-esque Gucci suits.

To that end, it would seem that the Sexton brand has returned to the Row just in time. As it did in the late Sixties, Sexton’s tailoring offers an antidote to the mediocre, and it is so sad that he won’t be able to witness the revolution for a second time.