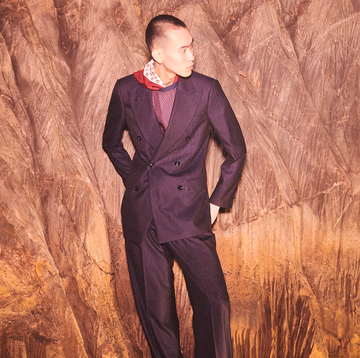

The first sight that greets a prospective customer at the Drake’s shop, at 9 Savile Row in Mayfair, is a display of four men’s blazers, hanging from hooks like wearable works of art. Recognisably related, each wall-mounted, ready-to-wear jacket is slightly different from the others, in fabric, texture, colour, detail and cut. The first is a navy double-breasted number with a fine herringbone pattern, patch pockets, mother-of-pearl buttons and peak lapels. Then a tobacco blazer, single-breasted, with notch lapels, in a lightweight cotton-linen blend. Then two more, a navy and an olive, in a heavy cotton twill. All are unlined, with soft shoulders — or “a soft shoulder”, for those fluent in rag-trade argot, where everything, even plurals, is singular: “Does Your Worship favour a black shoe with a grey trouser?”

What our discerning shopper is looking at is the Drake’s Games blazer, which comes in seven subtle variations, and is among the British brand’s most popular items. It is representative, in its combination of tradition and modernity, of the Drake’s ethos: “relaxed elegance”, as its founder Michael Drake put it when he started his label in 1977.

As demonstrated elsewhere on the shop floor by the skilful Drake’s merchandisers, the Games blazer can be dressed up as the top half of a suit, with matching trousers, shirt, tie and leather shoes, or dressed down, over a T-shirt, perhaps, with a pair of jeans and soft canvas trainers. All these items are also available at Drake’s, which has expanded, gradually but also dramatically, in recent years, from a maker of ties and scarves into a head-to-toe outfitter, with shops in New York and Seoul, as well as a thriving online

business. Today, Drake’s has appeal and influence across generations and demographics, from the City gents who typically frequent Savile Row — the geographic and you might even say the spiritual home of British tailoring — to a new breed of aficionado, enthused as much by contemporary streetwear and hype culture as by the arcane codes of formal men’s style.

On the afternoon of my most recent visit to Drake’s, this past March, I asked the man behind this transformation, the Drake’s co-owner and creative director Michael Hill, to give me a tour, starting with the Games blazer(s). A trim, 45-year-old father of two, Hill has distinctive coppery hair and white-blond eyebrows, and his features are as sharply cut as his suits. On this occasion, Hill — who, as those who follow Drake’s on Instagram can attest, makes a fine advertisement for his own brand — was wearing a navy fleece sweater, its breast pocket fastened with a popper, over a brushed-cotton check shirt, with bottle-green cords and a sturdy pair of black leather shoes. Only one of us was wearing a tie, and it wasn’t him.

This wasn’t Hill’s only way of dispensing with formalities; for all that his business address is redolent of a stiff-upper-everything and a military bearing, there’s no standing on ceremony at the Drake’s shop. The Games blazer, Hill told me, is designed to promote “comfort, ease and informality”. Not quite how they describe the coats, as suit jackets are confusingly referred to, a few doors down at Huntsman, or over the road at Ede & Ravenscroft.

“There’s absolutely nothing stuffy about it,” Hill said, as I fingered a handsome brown cotton-canvas example, silently calculating how many meals my dog would have to skip to afford me the necessary £695 to take it home. Unstuffiness in dress is hardly a radical idea in 2023 and yet, again, it’s not necessarily the vibe they’re pushing at Norton & Sons or Henry Poole & Co. Even the less hidebound Savile Row tailors, at Ozwald Boateng or Richard James, might balk at Hill’s suggestion that the best thing you can do with your new blazer is to “take it off and throw it in the washing machine”, the better to achieve a lived-in look.

Designed by Hill and his team in the office beneath the shop and made in Italy, the Drake’s Games blazer, to quote from the brand’s own blurb, “straddles the half-world between super sharp and slouchy” and typifies the ethos of “utilitarian workwear you can fine-dine in”. Drake’s makes suits and ties and tailored shirts for men who don’t have to wear them but choose to do so anyway, because they feel good and look right.

We moved on to the next display: four chore jackets — the workwear staple beloved of the creative classes — two denim, two suede, each accessorised with a floaty wool-silk scarf printed with images of tigers. Then, a sleeveless bouclé-wool fleece in neon tangerine, over a heavy denim shirt, with white Japanese selvage cords.

On the page, these might sound rather rarefied garments. In reality, they are simply better made and more considered versions of items most men with an interest in dressing well will already have in their wardrobes: a navy blazer, striped business shirts, jeans, T-shirts, sweaters.

“Classic” is a word that some fashion brands approach with extreme caution, fearing that the dread hand of tradition will indicate incipient obsolescence. So I use it hesitantly, but as soon as it’s out of my mouth, Hill seizes on it. “Yes!” he says. “We’re not trying to do anything revolutionary here. It’s still the classic stuff, but maybe put together in a slightly different way.”

The old ways of dressing smartly and stylishly, Hill says, were clearly defined. That was all changing long before the pandemic upended, for so many of us, the difference between dressing for work and for play. But there’s no doubt that the past few years have accelerated the trend away from formal and towards casual: the uniform of today’s white-collar executive, if there can be said to be one, rarely calls for a white collar.

“Now,” says Hill, “it’s, ‘What do I do? Where do I start?’ It’s harder to decide how to dress. There are more options now, and less rules. But, good! Because it’s exciting. You can really express something. And that should be enjoyable. It allows you to play a bit. And hopefully we can help with that.”

So Drake’s sells beautiful shirts, for business and pleasure — not that anyone there is interested in making the distinction — all made in its own factory in Chard, Somerset. Most representative are the button-downs, in a full spectrum of colours and patterns and fabrics (Madras, chambray, flannel, poplin, needlecord and the familiar Oxford cotton) plus, crucially, a rolling collar that lands somewhere between Boston Brahmin and Roman holiday.

Neckwear, the garments on which the Drake’s name was built, is made at the company’s factory in east London: silk ties, cashmere ties, wool ties, striped ties, plain ties, patterned ties, printed ties, tipped ties, hand-rolled ties, bow ties… Knitwear is made in Italy, or Scotland in the case of the Fair Isle jumpers. Denim comes from Okayama, Japan. Socks are Welsh, naturally.

Even a humble T-shirt, made in Portugal, is elevated with the use of substantial cotton jersey, a ribbed collar and double-stitched seams, reminiscent of mid-century Americana. Likewise hoodies and rugby shirts and sweats.

Provenance is key, as is quality and craftsmanship. The wool for the Drake’s tweed jackets comes from mills in Donegal, Yorkshire and Italy. The more formal suits are all cut in Italy, and a made-to-measure service will soon be introduced.

Also for sale, a curated selection of items complementary to the Drake’s house style, mostly by small-scale, cognoscenti-favoured brands: footwear from France (Paraboot), the US (Alden) and Northampton (Edward Green), home of traditional English shoemaking; knits from Mexico (Chamula); American outerwear by way of Japan (Rocky Mountain Featherbed). An ongoing joint venture with Aimé Leon Dore, the streetstyle-approved label from Queens, New York, has resulted in sweatpants, shirts, graphic scarves and more.

Witty and irreverent, the clothes and styling manage to tilt just the right side of whimsy. Western belts with wide-wale cords? Why not? And how about a Fair Isle balaclava while you’re at it?

While other luxury labels pursue collaborations with the global sportswear megabrands, Hill’s latest wheeze is a capsule collection with St John, the storied London restaurant group: a butcher’s-stripe chore jacket in moleskin, in homage to St John’s inimitable chef-patron, Fergus Henderson; red needlecord trousers; a navy Shetland jumper emblazoned with an image of a pig jumping over a fence. Why St John? Hill looks at me semi-aghast. Because it’s a really amazing place to have lunch, obviously! Because St John makes things with great care to the highest possible standards, and because it has style. “Not just in terms of the way they present themselves,” says Hill, “but knowing how to live.”

How to live: that’s a conundrum to which menswear offers many solutions, often contrasting. If masculinity is a construct, then clothes are building blocks of the persona. Who do you want to be today?

Men’s style, and British men’s style perhaps especially, is often painted in primary colours, as a series of polarities, resulting in cartoonish images that are hard for most men, even stylish men, to reconcile with their own tastes and desires and, well, lives. On one delicately manicured hand, you have effete peacocks who spend weeks agonising over the correct horn button with which to decorate their bespoke underpants. On the other tattooed mitt, blobby teen hype-beasts squandering their pocket money in online auctions of limited-edition “grail” sneakers.

Within a short walk of the Drake’s London shop one can find two homegrown exemplars of the best in formal menswear, and the best in streetstyle, both making exceptional clothes for men — and women, but mostly men. Around the corner on Old Burlington Street is Anderson & Sheppard, perhaps the most prestigious of all the Mayfair tailors, specialising in drape-cut bespoke suits and the other accoutrements of old-style plutocracy. On the other side of Regent Street, in Soho, Palace is London’s answer to New York’s Supreme, a skate brand that sells hoodies and logo T-shirts to fashion-obsessed kids of all ages.

You could — and, if you have the means, probably should — shop at both places. Not that we are in the business of issuing diktats, but you probably wouldn’t (and, possibly, shouldn’t?) go to the football in a three-piece tweed suit from Anderson & Sheppard, and you might hesitate to get married in a logo-heavy Palace tracksuit.

Drake’s triangulates the two: it offers classic tailoring and sportswear for men who want to be stylish, and even to stand out a bit, without being mistaken for Jacob Rees-Mogg, or Justin Bieber. Somewhere between preposterously traditional and terrifyingly trendy, between Jacob and Justin: the rest of us.

There is no typical Drake’s consumer, Hill says. Customers range from twentysomethings to septuagenarians, although the greatest concentration is probably men around his own age, with a bias, as you might expect, towards those working, as he does, in the creative industries.

While I attempt to theorise the brand’s appeal, Hill demystifies. “It’s just about putting classic clothes together in interesting ways,” he says. The Games blazer is part of the Drake’s Perennials collection. “That constitutes most of what we do. A lot of it doesn’t really change, but you’re always tweaking the cloth to make it feel fresh and relevant.” Broadly, Drake’s offers a winning synthesis of the three most influential approaches to men’s fashion of the second half of the 20th century and beyond.

The first is Ivy style, the mostly unbuttoned but nevertheless rigorously codified look also known as preppy, which 70 years ago transplanted the weekend uniform of the English country house to the postwar campuses of Harvard and Yale, softening it and then reselling it to the world: button-down collars, penny loafers, cardigans. The second is the nonchalant elegance of Neapolitan sprezzatura, the fine-tailoring tradition of southern Italy, with its just-off-centre aesthetic, its sensuous approach to smart dressing. Then, there’s the dandyism of traditional British formal tailoring, and our nation’s many subcultural reinterpretations of it. In its forensic attention to detail and determination to look sharp under all circumstances, Drake’s is indebted to the usual local suspects: Mods, Soulboys, Casuals and the rest.

So, Britain, Italy and the US. Plus, two further international influences: France (check out those chore jackets, with their insouciant scarves), and Japan, with that country’s distinctive and obsessive spins on mid-century British and American styles.

“We’re British by dint of the fact that we are here,” says Hill, now sitting in a meeting room beneath the shop. “We’re working with lots of British suppliers, and we make in Britain ourselves, so we’re British. But there are so many influences from elsewhere.”

Founder Michael Drake’s own suits were made for him by Gennaro Solito in Naples. “That’s so important for me,” says Hill. It has influenced the soft tailoring Drake’s creates now. “Does that make our tailoring Neapolitan? Is it British? I don’t know. It makes it Drake’s.”

The last time I wrote an article about Drake’s, in 2007 — it was for The Spectator, under the headline “King of Tieland” (see what they did there?) — I interviewed a different Michael: Michael Drake. My article focused, necessarily, on neckwear.

I visited the Drake’s factory, then in Clerkenwell, and watched as a tie was made to my own specifications, from the choice of fabric and pattern to the width: 8cm, please. Drake himself was expansive and charismatic, and his factory hummed with industry. His ties then were worn by well-heeled professionals, but most of them likely didn’t know it. The label stitched inside might have said Dunhill, or Turnbull & Asser, or even Comme des Garçons, all of which Drake’s made ties for. Only a small number of clued-in customers would have worn a Drake’s own-label tie, bought, perhaps, from Harrods in London, or Bergdorf Goodman in New York, or Isetan in Tokyo. There was no Drake’s shop then, but Michael Drake told me he was considering selling ties online.

In 2021, at the peak of work-from-home, The Spectator, which clearly can’t leave the subject alone, predicted that the time was coming when ties would only be worn by “eccentrics, dictators or eccentric dictators”. (Who can they have been thinking of?) This March, in an article for The New York Times, Peter Coy wrote that, “Neckties have been out of fashion for so long that even articles about neckties being out of fashion have gone out of fashion.” (Your correspondent, who prays that that last part is not true, has been recycling a piece mourning the demise of ties for upwards of two decades, for magazines and newspapers from Moscow to Mumbai; other territories that are in the market for original-ish content of this calibre need only ask.)

Coy, who more often writes about finance and economics, observed in his column that ties threaten to become a “stranded asset”: “something like a coal-fired generating plant that is no longer useful because of changes in regulation or technological obsolescence.”

Michael Hill was born into ties. His father, Charles Hill, owned and ran Charles Hill Silks, making ties under his own name and for Savile Row tailors, Jermyn Street shirtmakers and international luxury brands including Hermès and Ralph Lauren. At that time, Michael Drake was a scarves and shawls guy looking to get into ties. In 1982, Hill senior and Drake went into business. Hill & Drake, the label they founded together, sold ties under their own name (I recently found some nice examples on eBay) and to famous brands around the world.

From almost as early as he can remember — “certainly from the age of seven, maybe younger” — Hill junior accompanied his father on Saturday sales calls, to tailors and other clients, or to the factory.

“I loved being around cloth and colour and design,” Hill says, “loved going to see customers with him. At school, I always knew I wanted to do this. I didn’t have to worry about what career to choose. I knew where I wanted to be.”

Even in his pre-teens, the seed of the idea that would become today’s Drake’s was germinating. “I saw Michael and my father selling to the brands, making for Dunhill, making for Ralph Lauren, and I remember — arrogant little dick that I was — saying, ‘Dad, what are you doing letting them put their label on your work?’”

After school, he went to work as a gofer at mills in Biela and Como, in Italy. “Nepotism, pure and simple,” he says. “My dad got me in. But I just wanted to learn how the industry works. And I loved it.”

Hill grew up in the village of Cookham, in Berkshire. He studied fashion management at the London College of Fashion, at the same time as learning the ropes at Richard James — at that time, circa 2000, busy reinventing Savile Row tailoring for the Cool Britannia generation: actors, Britpop musicians, advertising honchos, celebrity chefs, media nabobs, the more telegenic faces of New Labour and, yes, even style journalists. “It was such a great place to be,” he says. “So exciting. And I learnt so much from Richard and [co-founder] Sean [Dixon].”

By then, Charles Hill had retired to Devon, having sold his own business to Turnbull & Asser. It was at Richard James that his son reconnected with Michael Drake. “I guess he recognised the little ginger kid he used to see on the factory floor years before, and we would talk.” Drake was now running his business with a new “tie guy”, Robert Godley. When Godley was poached by Ralph Lauren for a job in New York, Drake pounced.

“He called my mother and he said, ‘I think your boy might be interested in this — would you mind if I gave him a call?’ So we met at his factory, just down the road from my little flat in Old Street, and we started.”

That was 20 years ago. “I got so much from my father, but Michael Drake was also a very good fit for me. He’s an amazing man. And it was a great education.” The range of Drake’s clients, from high-fashion brands to traditional tailors, exposed the young Hill to different areas of the industry, and helped him see how and where Drake’s could fit in.

“I learnt about the product and the industry, but it was cultural, too: Michael showed me how to live! Everyone came into work, and you spent all day there. But then you’d go out every night. Hard work, but so much fun.”

Gradually, his idea began to develop. “When I joined, Michael was already in his sixties. What was the future? Businesses like that, if they weren’t evolving, they were dying. We started losing out to the Italians and then the Far East in terms of the customers we were making for. I knew we had a great product but we were £15 more expensive, so they were sourcing cheaper product elsewhere. Those brands had a strong name. They didn’t need us.”

More encouragingly, demand among individual customers was strong. “You would have people — Americans, Japanese, Italians — knocking on the door of the factory: ‘Is this your shop?’ No. ‘Where is your shop?’ We don’t have a shop. The best I could do is send them to [the shirtmaker] Emma Willis, who was our biggest customer nearby at the time. But

you don’t want to do that! You feel bad!”

While he travelled the world, selling Drake’s designs to the international brands, Hill thought of his old bosses at Richard James. “Richard and Sean didn’t travel to see customers. They set their stall out. They said, ‘This is who we are, people will come to us.’ And they did. So it wasn’t a difficult idea for me to think, ‘Hang on, if we do this ourselves, the customers might come.’” And they have.

In 2010, Hill and his new partner, Mark Cho, co-founder of the Hong Kong-based haberdasher The Armoury, bought Drake’s from Michael Drake. Hill became creative director. Drake stayed for a short while before retiring. His legacy looms large.

“It wasn’t a hard ending in the relationship,” says Hill. In fact, on the morning of our interview, Michael Drake had been in the shop, catching up on the gossip. “His is the opinion that matters to me most,” says Hill. “It’s really important to me that we do something that he ultimately will be proud of. I’m not saying we’ve achieved that yet. But the plan is that one day we will.

“In a way,” he continues, “what I’ve tried to do is take Michael and make a brand out of him: his style, his attitude.”

That attitude, says Hill, is “stylish and generous and very rich in an understated way. Not taking life too seriously. Living well. But that doesn’t even begin to describe it. I think it’s about being curious about other cultures, enjoying other cultures, being respectful to the heritage of craft. You’ve got to be proud of what you’re doing, haven’t you?”

To Hill, Drake’s progress seems slow. But he’s inside the beast. To style-watchers, the transformation from niche neckwear manufacturer to an internationally recognised brand with outposts on three continents has been spectacular. Drake’s still makes ties for other labels to stitch their logos into, but that has become a small part of the overall business.

“We had to be careful in winding it down,” he says. “We couldn’t afford to say we’re only going to do our own thing. We needed that private label business to be able to pay people. It’s been a constant fight, and then the last few years happened.”

It’s no news that the pandemic was difficult for makers of formal men’s clothes. But Drake’s has weathered the storm — the business year that ended in April was their best so far. “It’s hard work,” says Hill, “but it doesn’t feel like work, because we’re doing what we love.”

He has big ambitions for Drake’s, but he doesn’t want to rush anything. At some point, he’d like to move to a different shop in London. He’d like to expand the business in Japan. The New York shop, on Canal Street, only opened last autumn. He knows there’s more to be done with the website. He would like to attract more women as customers. “The process of growing a business is very fulfilling,” he says. “You learn a lot about yourself. And hopefully we’re at the start. We’re just beginning to figure it all out.”

He knows what he doesn’t want to do. “Ploughing a load of money in to open millions of new stores all over the world, sourcing your product more cheaply to grow your margin? No. You’ve got to grow slowly and sensibly. Otherwise you’re going to lose your original customers, and that’s a disaster.

“Whatever we do,” he adds, “it’s got to be gentle. It’s got to be classic.” Drake’s clothes are “things you can go back to, and wear again, down the line, and for the rest of your life. That’s what it’s all about: great product, great craft, great style, great people, for the long term.”

The only urgency, then, is my own: how to get myself inside one of those Games blazers in time for summer. Anyone in the market for a piece about the demise of the tie?