Alas, I was unable to attend the launch of the Chopard Alpine Eagle earlier this year. It was held in Gstaad, and I like Gstaad, by Karl-Friedrich Scheufele, and I like him too. Oh yes, and I like the watch. The brushed dial is beautiful, the second hand shaped like the tail feather of an eagle is a nice touch, and the timing of the launch seems spot-on.

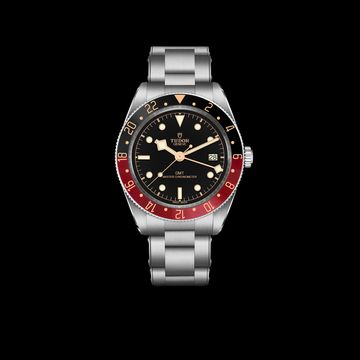

The obsession with steel sports models seems to show little sign of abating. Oak and Nautilus have ignited a sort of collective hysteria among those for whom the Nautilus scarcely existed barely five years ago. Of course, the internet has made experts of us all and these “collectors” are no exception: having discovered the genius works of Gérald Genta, they now seem to see the world entirely through the prism of his best-known designs, judging every new steel bracelet watch to come on the market by the standards of these two classics. All in all, this is about as useful as comparing every painting to the oeuvre of Picasso.

You can view the Alpine alongside the two giants of the integrated case and bracelet steel watch if you want, but it makes more sense to see it in its own context. First, the Alpine Eagle is, in a manner of speaking, its own inspiration. Thirty-nine years ago, Karl-Friedrich Scheufele, then a 22-year-old man about Geneva, wanted to make a watch for people of his age group and came up with the St Moritz. Put an Alpine Eagle side-by-side with a St Moritz and, size aside, the difference is in the details. It is, in broad aesthetic terms, a revival of an archive model from a discrete and intriguing period of watch design that deserves to be examined on its own.

The St Moritz appeared at the same time as two other memorable bracelet watches: the Cartier Santos (1978) and the Piaget Polo (1979). These are the contemporaries of the St Moritz, and they heralded the disco-glitz of the early Eighties. Cartier, the long-established jeweller, was being transformed from a trio of boutiques in Paris, New York and London into the titan it is today, by Alain-Dominique Perrin, one of the great architects of modern luxury. The steel, bi-colour, or solid gold versions of the Santos chimed with the seductive, shiny newness of the Les Must de Cartier era.

Yves Piaget, meanwhile, had transformed his family’s movement supply business into an elite niche brand famous for high jewellery pieces of great imagination and slim, exotic-dial men’s watches that fitted perfectly with the aesthetic of Harold Robbins’ heyday. The Polo was a work of genius: case, dial, bezel and bracelet eliding seamlessly into a unified creative whole, available only in 18-carat gold.

Coming at the same time, the St Moritz was the sporty expression of a watchmaking house that, under the guidance of the Scheufele family, was ploughing a new furrow in creative watchmaking; it should not be forgotten that in 1976, the Happy Diamond made its debut... as a man’s watch.

The Santos has been revived with spectacular success by more or less photocopying the original; the St Moritz has been brought back as the Alpine Eagle. But what of the Piaget Polo? (I am purposefully ignoring the recent watch to carry that name which appears to have been ever so slightly, ahem, “inspired” by the Nautilus.) If Chabi Nouri, or anyone else at Piaget, is reading this: the revival of the real Polo is overdue.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.