On the morning of our final meeting for this article, in mid-September, Tony Blair gave me a tour of the art on display in his London office. On a wall facing his desk, on the far side of a substantial room, is a 19th-century painting of a Cairo street scene. On another, a present from Cherie, Blair's wife: a black and white photograph of an Orthodox Jew sitting beside a market stall. On a third wall, a painting of pilgrims on the outskirts of Jerusalem, also 19th-century. Most imposing is a large map of Africa and the Middle East. As we looked at it, Blair marvelled at the size of Africa, and then he pointed out Israel — we'd been there, together, a few days earlier — and remarked on how tiny it is compared to the Arab states surrounding it.

We continued the tour. Alongside the family snaps of Tony and Cherie and their four children, now all grown up, there's an eye-catching photograph of two small boys playing football on a dirt pitch in, he thinks, Rwanda — another country we'd visited together. Looking around the room, I made some bland comment on the fact he was surrounded by images of his present preoccupations, the concerns he spends the majority of his time on, and that he returns to most regularly in conversation: peace in the Middle East, economic and political development in Africa.

I confess I hadn't noticed that other than a maquette for a statue of Harold Wilson, the Labour prime minister of the Sixties and Seventies, there were no obvious representations of Britain, or Britishness. But I think Blair noticed, suddenly, because as soon as I made my remark he took off at a clip, opened the doors to an adjoining sitting room — I grabbed my voice recorder and scuttled along behind him — and began to talk me through the pictures on the walls: British scenes by British artists. It's a fraught business, the giving of interviews, the management of a public reputation, especially one such as his.

The Office of Tony Blair is an organisation — you might even say an idea — as well as a physical space. It is headquartered, for the moment, in a terraced townhouse — stucco ground floor, brick above — on a corner of Grosvenor Square: prime Mayfair real estate. Blair left Downing Street in 2007 with, as he put it to me, "three people and four mobile phones: no office, no back-up, no nothing." In the nine years since, he has built a new infrastructure to enable him to do all the things he wants to do. (There are many.) He now employs around 200 people on his various ventures, philanthropic and otherwise. These are funded by his own money, earned through his commercial work, as well as the donations of high net-worth individuals (extremely rich people, in human-speak), and in some cases, the aid and overseas development budgets of foreign governments. Building this organisation has been perhaps his most consuming task since stepping down as prime minister.

Like the American embassy on the other side of Grosvenor Square, which is to relocate south of the river, the Blair office is to move to more modern surroundings. He is bringing all his different enterprises under one roof. He estimates he already spends 80 per cent of his time on pro bono work, and it is his intention to close down the business side of his operation, Tony Blair Associates, winding up both Firerush (which advises governments) and Windrush (which advises individuals). He will keep some of his paid-for consultancies — the most lucrative of which is his work as an adviser to JP Morgan, the American bank, which pays him £2m each year — and he will still accept speaking engagements, but the more (or most) controversial aspects of his work since stepping down as prime minister will cease.

Broadly, Blair works now in four areas: promoting and helping to implement good governance in Africa and the developing world; building a framework to launch a new peace process in the Middle East; coming up with ideas to combat the ideology of fundamentalist Islam; making the intellectual argument for the centre-ground in politics. He also has a foundation promoting sport, and another promoting inter-faith relations.

Blair is extremely busy, that much I was able to glean. Each moment of each day that I spent with him was accounted for. One meeting is followed immediately by the next. He starts early and finishes late. He rarely breaks for lunch. In fact, he does not seem to eat lunch. The concept of the weekend, too, seems somewhat irrelevant to him. (He remains a big fan of holidays, though.)

What, exactly, is he doing? Why is he doing it? There may not be simple answers to these questions. It sounds, perhaps, ridiculous, but the closest I can get to a job description is that Blair has set himself up as a sort of freelance diplomat, a statesman-without-portfolio. He is an adviser to foreign governments, as well as to private companies. He is a political strategist and policy analyst. He wants to rethink the way the West tackles extremism in all its forms; he wants to rethink the way the West gives aid to developing countries; he wants to make the case for a new kind of radical, pragmatic, centrist geopolitics: a Fourth Way, perhaps. If we were going to speak in woolly generalisations — and clearly we are, or I am — he wants to bring people together rather than pull them apart, build bridges rather than put up walls, to champion that increasingly unfashionable idea: globalisation.

Is he kidding himself? Is anyone listening to him? Isn't it a bit late for all this? Blair is, of course, a polarising figure, here and abroad — but especially here. In fact, in Britain polarising doesn't cover it. His brand is toxic. The story of his life, his achievements — whether you think what he achieved is a triumph or a disaster, it would be difficult to argue that he hasn't achieved anything — are all overshadowed by the run up to the invasion of Iraq, the invasion itself, in 2003, and its horrific aftermath.

Blair left office under a cloud and in the nine years since, the skies have not cleared. If anything, they've darkened. The cartoon of him drawn by the media is of a man who is avaricious — why is he so rich? — as well as hypocritical — why does he associate with tyrants and tycoons? — and deluded — why can he not accept that the invasion of Iraq was, at best, a terrible mistake? Then there are those who really don't like him, who say he is a liar, even a war criminal.

Blair says that since there is not much he can do about his reputation, especially at home, he has learned to be philosophical about it. He told me he accepts that few in Britain are listening to him. That is why he tries to affect politics overseas. But I sense — though he says it's not so — that he is also engaged in a reputation-rebuilding exercise. Certainly the closure of Tony Blair Associates could be seen as part of that exercise. Perhaps he views this piece as part of it, too. Perhaps it is.

In May, after Blair was interviewed by the BBC's Andrew Marr, The Times ran a piece under the sneering headline, "Blair: I'm not too rich and do lots of very good work". The implication of the headline was clear: he is too rich and he doesn't do lots of very good work. I hoped, with this article, to avoid falling into both those traps: the perceived whitewashing of the Marr interview and the sarcasm and cynicism of The Times piece.

(The Times, of course, is owned by Rupert Murdoch, a former friend of Blair's. I mentioned to Blair that that newspaper, in particular, has it in for him. Not that the Daily Mail, and the Guardian, and, in fact, all the other British newspapers don't. Just that The Times attack on him is particularly aggressive and sustained. He rolled his eyes, raised his eyebrows, and gave a bewildered shrug, which is what he sometimes did when I mentioned something that he didn't want to comment on. It's an effective strategy; you can't quote a bewildered shrug.)

It's not true to say Blair is universally disliked, here or anywhere else. Not everyone I spoke to, socially and professionally, during the months I was working on this piece, on and off, was violently anti-Blair. But most were. Some made disobliging remarks about his private life. Plenty of people expressed strong reservations about the wisdom of my putting him on the cover of this magazine, some simply because he is unpopular, so the magazine wouldn't sell, others because he didn't "deserve" to be on the cover, as if I were giving him an award of some kind. (I'm not. I'm merely suggesting that, for good or ill, he is one of the 25 most influential British men of the past quarter century, which is a different thing entirely.)

Others suggested I was either a Blairite apologist, or I would come across as one. They thought I would be spun. There certainly were moments when I felt I was being politely guided towards a toothless portrayal — that visit to a solar power plant in the Rwandan interior: impressive, sure, fascinating even, but perhaps not entirely germane to this story — but then you'd hardly expect his team to direct me towards murkier goings-on, if there were any. I'm not sure anyone can approach the topic of Tony Blair without prejudice, but I tried to keep an open mind.

I first went to Grosvenor Square to meet Blair in April of this year. We'd already agreed with his people by then that he would give an interview to Esquire for this, our 25th anniversary issue. While Blair poured coffee, I told him that my intention was to write a piece about his life now. I said I wasn't interested in point-scoring or party politics — "Lucky you!" he said — but that I wouldn't be doing my job if I didn't ask him to talk about topics he'd probably rather not talk about, in particular the Iraq War and its repercussions. He said that in that case, the main interview would have to wait until after the publication of the Chilcot Report, still some months off at that stage, but until then I was welcome to watch him at work.

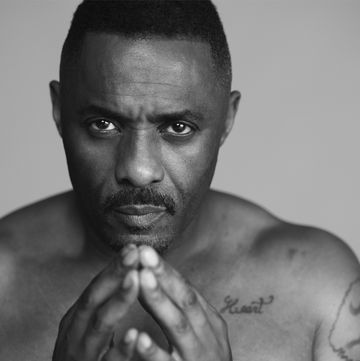

Blair is 63. In the years since 2007, his hair has greyed and thinned. He looks older, because he is. But his eyes are still bright blue, his skin is still tanned, he is still as slim as a student. He was dressed, at that first meeting, as he was dressed at almost every other meeting to come, in the style of a senior business executive: sober navy suit over crisp white shirt, the top two buttons undone to reveal glimpses of a thin gold chain around his neck. If you didn't recognise him immediately, you might peg him as an investment banker, or the CEO of a media conglomerate. (Or an incumbent world leader.) I did notice one eccentric touch. On more than one occasion he wore black suede RM Williams boots — you know the ones, with the elastic pull-tags at front and back. Not that there's anything especially rock 'n' roll about wearing suede boots with a business suit, but it's a modest signal: I'm not like all those other stuffed shirts.

(It's nice for him, of course, that he's in good nick. But I sense it antagonises his opponents: Blair looks healthy and comparatively youthful and prosperous and energetic when really he should be pale and cowed and aged and, and, and… it's not fair! Plus, he wears groovy boots which is, you know, suspect.)

Blair has an uncommonly mobile and expressive face. He's forever grinning — flashing those famous snaggleteeth — or frowning or grimacing or expressing surprise. And actually, for someone often thought to be good at hiding his true feelings — the king of spin — his face gives him away. When he's bored or frustrated he looks really bored or frustrated. And when he's faking it, it's obvious. It was always quite plain to me if I'd asked him something interesting, or made a perceptive remark (it happened rarely enough), or if I'd disappointed him with a dullard's observation, or a sophomoric question, especially one I'd already asked, and was now trying in a different way, hoping for an alternative response. At those times he looked exasperated.

All the quotes in the Q&A sections that follow are taken from the final interview in London while others threaded through the piece are from conversations we had at other times.

Excerpts from an interview with Tony Blair, London, 15 September 2016 - Part One

You were an incredibly popular prime minister, at the beginning. Nevertheless, you're going to be remembered as the man who invaded Iraq. Does that feel like an injustice to you?

"It doesn't feel like an injustice. But I think over time these things play out differently. On Iraq, I think it doesn't help anyone for me to keep relitigating it. People have their own views about it. I think in time people will come to a more measured view about why it was done, and its consequences, but who knows? I don't spend a lot of time reflecting on that. I'm much more concentrated on what I'm doing now."

No prime minister leaves office more popular than they came in. But the difference in tone is particularly marked in your case. Are people just wrong about you?

"It's not that people are wrong it's that… As I've often said, when you decide you divide and if you take difficult decisions, you're going to make yourself unpopular. You will become a controversial figure. But I came to the conclusion that the responsibility of leadership is to do what you think is right, irrespective of whether it's popular, and that is a difficult thing to do, but in time I think people accept that."

I was at your press conference on the day of the Chilcot Report. As you walked in, the man behind me said you looked "shell-shocked". Is that an accurate description of how you felt?

"No, it's not. I wasn't. I was cognisant of the importance of the occasion and the importance of the debate. The conclusions in the Report weren't particularly a surprise to me because through the process called Maxwellisation you get a fair idea of what's going to be said [in advance]. But I wanted to give a complete statement on my position, which I did, and to answer any questions that people had. When I said, 'I accept responsibility', I did, and it's important to do that. But I was very clear where I stood on the issue, and where I stand on it."

Were you surprised by the contents of the Report at all? Was there any of it that you didn't know in advance?

"No. There were bits of it that I profoundly disagree with but there's nothing that particularly surprised me."

Sitting there, in Admiralty House, watching you, it struck me that you were — you are — being asked to carry the can for a lot of world events that took place at that time, in 2003, and in the aftermath of 2003, single-handedly, as though there was no one else in the room and there weren't any other countries involved. Does it feel like that to you? That's how the media present it: "Blair's War".

"Yeah, it is how they present it. But I'm someone who doesn't mind taking responsibility. And because I think the issues are so serious and they live with us still today, and because I have, frankly, a profound disagreement with the way the West is handling the whole issue of radical Islamism, I'm content to take responsibility because I believe that in time people will understand this is not a problem that we have caused, it's a problem that we have got caught up in. And that there are going to be no easy solutions… With all the lessons of Iraq, we've still got a massive problem. And of course, the worst problem we have is in Syria, where we didn't intervene at all."

Some might say the reason we didn't intervene in Syria is because of what happened in Iraq. It turned Britain and the West off intervention, full stop. That's the legacy of Iraq.

"Right."

If you'd still been in power we probably would have boots on the ground in Syria. Correct?

"We would certainly have been much more heavily engaged. Whether it would have needed to be our boots on the ground is another matter. But my point very simply is this: if we'd learnt the lessons of Iraq and Afghanistan properly, both in respect of Libya and in respect of Syria, what we'd have realised is that the problem is not removing the regime, the problem is what happens afterwards. Because there are bad actors who come in and destabilise the situation, which is why I favoured, in respect of Syria and Libya, an attempt to negotiate with Assad and indeed with Gaddafi to get an agreed transition. However, once you have set your face against that, you've got to go and get them out because otherwise you're going to end up with the situation we've now got in Syria, which is a catastrophe, and a shameful catastrophe in my view."

But you can't have a war without popular support for that war. And because of what happened in the aftermath of Iraq, there isn't popular support for intervention. It's perceived by the public that us going in and meddling in other people's affairs causes more grief to us and to them than not going in.

"No, absolutely, that's right."

If David Cameron had felt he had popular support he probably would have gone into Syria.

"That is absolutely the analysis, but what people have got to bear in mind is that we have now had full intervention with boots on the ground, which is Iraq, partial intervention in Libya, without boots on the ground, and no intervention in Syria. And actually in only one of these countries, which is Iraq, is there a functioning government that is recognised as internationally legitimate, including by Saudi Arabia and Iran, and is actually capable of fighting terrorism. Now, maybe the Libyan government is getting there now but in Syria it's a nightmare. So my point is very simple. I take a far longer perspective on this. It's why I think Western policy is in the wrong place. The reason that [Western intervention, in 1999, in] Kosovo worked and in Iraq and Afghanistan it was really difficult was because of the intervention of radical Islam, either of the Shia variety promoted by Iran, or of the Sunni variety promoted by Al Qaeda, Isis and all these other groups. It's a global problem. It's grown up over a generation and it's going to require a completely different and more comprehensive strategy to defeat it. I've written about this, but it's very difficult for me to make those arguments and frankly a lot of people aren't listening at the moment. But they will in the end because I'm afraid this problem's going to get worse before it gets better."

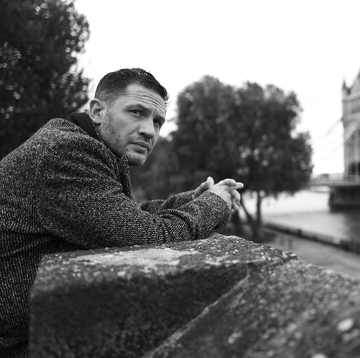

The sun came out for the publication of the Chilcot Report, on 6 July. At 2pm, inside Admiralty House, on Whitehall, in a square, high-ceilinged room with garish yellow wallpaper, in front of four TV cameras and perhaps 40 people — journalists, security heavies, his own team — a man, a once powerful and popular man, a man who was the future once but now seemed like the past, the past many would like to forget, was about to try to defend his name against apparently insuperable odds.

Tony Blair entered stage right and placed his notes on a grey lectern. He looked nervous. Ashen, even. The atmosphere was not, as you might imagine, febrile or electric or any of that. It was quite sombre and hushed. Blair's voice seemed hoarse at first, as he began his statement, but he didn't reach for a glass of water. He spoke for almost 40 minutes. At times he struggled to keep his composure.

He described the decision to go to war in Iraq as "the hardest, most momentous and agonising decision" he'd taken as prime minister. He said that he accepts "responsibility in full — without exception or excuse".

He admitted that the intelligence statements made at the time of going to war "turned out to be wrong". He accepted that the aftermath of the invasion was "more hostile, protracted and bloody than we ever imagined". And that instead of free and secure, Iraqis became instead "victim[s] of sectarian terrorism".

"For all of this," he said, he felt "more sorrow, regret and apology and in greater measure than you can ever know". His voice cracked on the word "sorrow". Afterwards, some reports claimed that his eyes filled with tears. I was in the third row, close enough to him to have seen if that were the case, and it didn't look like it to me. He certainly seemed stricken, though.

There were two things, he said, that he could not say. The first was that the removal of Saddam Hussein was the cause of the terrorism in the Middle East today. The world, he said, was "a better place without Saddam". The second was that those British soldiers who died, or who were injured, did so "in vain". They did not, he said.

He said that the Report cleared him of lying, or deliberately misrepresenting the facts, and he went on to give an account of his reasons for committing Britain to war. He rejected Chilcot's findings that military action had not been "a last resort". He said there was "no rush to war". He said he had had to make a stark decision — yes to war or no to war — and that he stood by it.

He asked us — the people in the room and everyone else — to put ourselves in his shoes at the time. He asked, "with humility", that we accept he acted "in good faith". He went on to address the failures in planning for the aftermath of the war, the British alliance with America, the intelligence about Saddam's chemical weapons, the credibility or otherwise of the legal case for the war, and to draw conclusions about what future leaders should learn from Iraq and Afghanistan. His message was one of hope for the Middle East.

I don't think it's incorrect to say that this is not what most people wanted to hear. They wanted to hear him say that he had done the wrong thing by leading Britain into the invasion of Iraq. That even if he had believed it was the right thing to do at the time, for the right reasons, he now accepted that he shouldn't have done it. There was never the remote possibility that he would do this, in my view, because he really does believe that invading Iraq was the right thing to do, and that he did it for the right reasons.

When Blair had finished he said he would take questions. For almost an hour and a half he did so, becoming much more animated, raising his voice. He asked that people "respect my point of view". He kept hoping that people would "read the report for themselves" rather than rushing to judgement — a vain hope, given the report is 2.6m words long.

"It overshadows everything people think about me," he said, at one point, of the Iraq War. "Please stop saying I was lying," he asked, at another. He ended with a quiet, "OK, I think that's enough. Thank you." Exit pursued by policemen.

"Poor Tony," said one man, along from me. I don't think he meant it entirely unkindly.

Outside in the streets of Westminster, people were demonstrating against him. On TV, the sister of one of the 179 British service personnel who died in Iraq accused Blair of being a "terrorist". The grandmother of another called him a "bloody murderer", and the father of a third said his son had died in vain. The headlines were uniformly condemnatory. "A Monster of Delusion", said the front page of the Daily Mail. "Blair's Private War", thundered The Times. "Weapon of Mass Deception", ran The Sun's headline. In the Guardian, Jonathan Freedland's column was titled "Blair Damned for the Ages." And the ordure kept being shovelled on for weeks afterwards. George Galloway's documentary, The Killings of Tony Blair, was released shortly after the Report. Tom Bower's biography, Broken Vows, shot up the paperback bestseller lists. In an essay of more controlled fury in the London Review of Books, Philippe Sands, the human rights lawyer, wrote that the war on Iraq and the controversies surrounding it "may come to be seen as marking the moment when the UK fell off its global perch, trust in government collapsed and the country turned inward and began to disintegrate." Which is quite a legacy for a British prime minister. The title for Sands' essay: "A Grand and Disastrous Deceit."

Excerpts from an interview with Tony Blair, London, 15 September 2016 - Part Two

I'm going to read you a paragraph from The New York Times, from 7 July, the day after Chilcot. I chose it because I imagine that The New York Times is slightly more dispassionate about you than some of the British papers.

"Yeah, but they're very hostile to any intervention."

This is the news report: "Prime Minister Tony Blair of Britain went to war alongside the United States in Iraq in 2003 on the basis of flawed intelligence that went unchallenged, a shaky legal rationale, inadequate preparation and exaggerated statements, an independent inquiry into the war concluded." That's their factual report of the findings of the Chilcot Report. It is a devastating summary. Do you disagree with it?

"I disagree with all the summaries like that. First of all there are elements that go on the other side of the ledger in respect of all of these things. For example, people talk about flawed intelligence without talking about the final reports, which actually go into detail about what the intentions of the [Iraqi] regime were and what the future would have held if we hadn't removed it.

"And in the end, you've still got two very fundamental questions that you have to answer. One: What would have happened if we hadn't [invaded]? Would the world be more safe today, or not? Secondly, for me as the British prime minister, there was a big question: were you going to side at that point with the Americans, or with those led by Russia who were opposed to the intervention?

"Now, if people are going to take a different point of view, just as I've got to face up to the consequences of my actions, they have to face up to whatever the consequences would have been if a different decision had been taken. In the end, everything that could be said has been said on both sides of this argument and if people want to know in depth my response, they should go and read my statement on the day and they will see where I accept responsibility, where I accept that there were real failures and apologise for them, but also where I put the rationale for doing what we did and why I believe that we are actually safer today without Saddam than with him.

"But people can disagree with this, and, as I said to you right at the very beginning, and I fear I've already disobeyed my own instruction, you can relitigate this the whole time, but most people have already made up their minds on this issue, and I accept that the opinion of people is as it is. There's no point in me carrying on trying to change people's minds."

"I will be with you, whatever." That's what the news led on, the words that you put in a memo to George W Bush in 2002. Do you regret saying those words now?

"No, because it's perfectly obvious from the rest of the [memo] that this was not unqualified. By the way, at the time we were trying to persuade the Americans to go to the United Nations and indeed they did go to the United Nations as a result of our persuasion. And secondly, you will find if you read the whole of the note that it's listing all of the difficulties. So what I was saying is, 'We're going to be with you in dealing with this, but here's how we're going to have to deal with it.' I think the very next word [after 'with you, whatever…'] was 'but'."

I ask about it partly because it has been, continues to be, and will always be used against you.

"I promise you, if it wasn't that it would be something else. This was the hardest decision I ever had to take, and I have never disrespected people who take a different point of view. The only thing that I ever protest about is when people say, 'You did it for motives that you have not disclosed.' Or, 'You did it for nefarious reasons.' I didn't. I did it because I thought it was right. Whether I was right in thinking it, that's a matter of opinion."

You have spoken of a moral component to the decision. Removing Saddam Hussein, whatever the political reasons or the security reasons, there's a moral dimension to it. People find that difficult because that wasn't a stated reason for doing it. You didn't say, at the time, "Morally we ought to get rid of him." You said, "He has weapons of mass destruction and strategically we ought to get rid of him and, also, he's a very bad man." Which is different.

"Yeah. But the whole point about a regime that is aggressive, and if the nature of the regime is also bad, then that aggression is much more of a threat. Why is North Korea with the nuclear weapon frightening? It's frightening because of the nature of the regime. So, actually, if you go back and look at the speeches I made before March 2003, they were all always about the nature of the regime as well, and the fact that — people forget this — when Saddam used chemical weapons in the Iran-Iraq War where, after all, there were a million casualties in that war, that was an event that wasn't just an act of aggression regionally. Out of that came the Iranian nuclear programme. It also had a bad impact on the world. So, this is why it's always a slightly artificial distinction."

But if we followed this line, then we ought to get rid of the regime in Iran, now.

"Well, I mean, I always say this to people: you can't get rid of every bad regime, and neither should you. But in my view the fewer of these regimes there are, the better for the world."

David Davis and Alex Salmond want the Commons to pass a motion accusing you of contempt of Parliament. What do you have to say to them?

"Nothing."

Nothing at all?

"No."

John Prescott believes the invasion of Iraq was wrong. What do you say to him?

[Blair sighs.]

He was your deputy prime minister!

"I know, but John, I'm afraid, buys the whole line that has now gripped, I'm afraid, a large part of the left, which is to say all these problems of extremism come from Western foreign policy. It's a fundamental mistake. And it ignores the history of how this radicalism has grown up and it confuses Western policy because at a certain point you start to play into their whole propaganda exercise against the West. Essentially you boost [the Islamists'] line, which is, 'We're having to do this because you guys are making us.' What? We're making you drive cars down streets trying to kill as many people as you can? I mean, why? OK, you completely disagree with what we did in Afghanistan and Iraq, but how does removing a brutal dictatorship that the people of that country most certainly do not support, giving them a United Nations-led process of election, and unlimited amounts of development aid, how is that oppressing them?"

It's not that it is oppressing them, it's the fact that subsequently their lives were made hideous.

"But therefore what we should do is identify the people doing the killing and work out how to defeat them and not say, 'No, I'm afraid you've just got to live under these brutal dictatorships because that's just the way of the world.'"

How much help has your own faith been to you during these periods when you personally have been attacked?

"If you ask someone of faith then it's always a great support because it's what you believe. But it's less to do with that than to do with the fact that I know in my own mind that I have done what I thought was right, and therefore I don't… That is to say, I'm not saying I was right, either on Iraq or anything else, but…"

But you do think you were right.

"I don't think it in some sort of Messianic way: 'I'm always right.' This sort of ridiculous parody of my thinking that's often put forward. No, I went through a very cold, hard process of reasoning to take the decision. And I look back now and because I'm the person who took the decision, I'm also someone who reflects upon it an enormous amount. The reason I'm out in the Middle East doing all the things I am doing there is in part because of all the controversy I was involved in, in the region and around the whole issue of radical Islam."

If I had done something I believed was the right thing to do — in every sense, morally, strategically, whatever — and I received the amount of opprobrium that you have and continue to, I would be angry. Really, I would be angry. Not just a bit miffed. I would feel a tremendous sense of unfairness.

"Yeah, but there's no point… I mean, I have found throughout my life that anger is always an energy that diminishes you. It never resolves anything. Look, you've also got to think: it's a great privilege to have led a country as great as Britain for 10 years. In many, many ways, I live a very purposeful and fulfilling life. I've got a lovely family. I count my blessings. I meet a lot of people in the work I do around the world who are so much worse off, and in so much greater difficulty than me. And I don't mean to sound sort of pious about it, but, ultimately, especially when you're doing these jobs under pressure, you do go through the furnace of it and you come out different."

Tougher?

"Tougher and also more balanced, with a greater equilibrium in your temperament. You realise that sometimes there's an anger that can give you purpose, and there's an anger that can just eat you up. And that anger that gives you purpose is when we were in Africa last week and you still see all that poverty and you think, 'We should be doing something about that.' That's a positive energy. The anger that says, 'People are treating me really unfairly'? I mean, look, the Chilcot Inquiry, by the way, not that you'd know it, found that we had acted in good faith throughout, as did the previous five inquiries."

"In good faith" is a phrase that you use a lot. The thing is, people think, "Well, I understand acting in good faith. But if it was the wrong thing to do it's still the wrong thing to do."

"And that's fair enough. But a lot of the opprobrium is around integrity, which isn't fair."

People think you acted in bad faith.

"As I say, it's a difficult situation with me with the British media and it will continue, probably, to be. Because I think there are other political reasons why my type of politics at the moment is not where the mood is."

Why would that make the press particularly poisonous in your case?

"Because they don't like the centre."

Because it helps the press to have a polarised politics?

"Yes. Look, I believe there are very powerful people on the right in the media and elsewhere who want to turn British politics essentially to the Eighties."

Because it helps to sell newspapers?

"But also because it helps to drive a right-wing agenda. What you had in the Eighties was a Labour Party that thought it was principled but in fact was unelectable, and a Conservative Party that could pursue its position strongly because there wasn't really the prospect of being knocked out by the opposition."

Are you going to say who these right-wing people are who are driving that agenda?

"Not for the moment."

Why would you not want to say that?

"There are some battles I want to fight and some I don't, at the moment."

You mentioned your family. All this must take a toll on them. They didn't choose to be at the centre of these controversies. It would be easier for them if you were perceived as a more benign figure.

"Yes, that's true. On the other hand, by some sort of good fortune, the children seem incredibly balanced with it all. We're just very lucky."

It must have been difficult to give them a normal upbringing?

"Yeah. Obviously it's an unusual life on one level, but I think I was the first British prime minister to send my children to state schools and we were lucky to find good state schools in London, and I think going there helped because they mixed with a broad range of children and they seem, touch wood, to be fine."

Rwanda: a small, lush, landlocked country in east Africa, traumatised by the savagery of its recent past and ruled by a ruthless moderniser, a former rebel leader who has fast-tracked his nation from what was, 20 years ago, close to a failed state to one of Africa's economic success stories.

Kigali: a sun-blessed, orderly, clean capital city — almost pathologically clean, as if the city itself has OCD — of ridges and valleys, most thrillingly navigated as a helmeted passenger on one of the motorbike taxis that wriggle through the traffic, buzzing like mosquitoes.

It's May, and Tony Blair is in town for the World Economic Forum on Africa in his role as founder and patron of the Africa Governance Initiative. Funded by rich donors (at various times: Bill Gates, Lord Sainsbury), this is a development charity with a difference: rather than offering aid, in the traditional sense, its operatives are embedded inside the government — the president's office, various ministries of state — to help implement policy. They are, one of them tells me over a drink, "all about getting shit done".

Blair is a big man in Rwanda. He is, according to a student I chat to in a sports arena in Kigali, while we wait for Blair to arrive and bowl a cricket ball for charity, "one of the best friends of our president". ("One thing about being a known face is, you might as well use it," Blair says, when I ask why he still bothers with the comedy photo calls.)

The President is Paul Kagame. He came to power in 2000, six years after the genocide that killed 900,000 people in 100 days, and he is one of Blair's longest standing developing world partners. A sinuous, studious-looking man, Kagame has made a great success of Rwanda's economy, but his administration and armed forces are accused of human rights abuses at home, as well as of brutal military incursions into the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo.

Blair likes it here. He likes the energy. "This is an amazing country," he tells me. "It's a place on the move." I join him and his team for breakfast at the brand new Marriott Hotel, where he is staying. We are close to the convention centre, inside a temporary "red zone". To get to him one must pass through road blocks and multiple security checks. Many of the continent's leaders have gathered here, along with Western diplomats and investors in Africa from around the world.

During his time here, Blair has meetings on such topics as import substitution, energy policy, cement production. (It's only rock 'n' roll but he likes it.) On all of these matters, members of the AGI team are working with the Rwandans to help them, to use the deathless management speak, "deliver on their targets".

"What is the essential thing to recognise about the world?" Blair asks me, as we sit in the shade on a terrace at the back of the hotel. "It's that the countries that govern themselves sensibly, as opposed to those that have pursued daft ideologies or become corrupted, do better. If they govern well, there's no limit to what they can do. But the hardest thing is to get things done. How do you actually have a plan, prioritise and deliver it?"

As ever, Blair is not thinking small: "I want to change the way we do development." When he says "we" he means "the world". "I want to influence global policy on this. That's one thing you can do when you leave office: you can influence."

I watch him tour a high-tech lab where students are learning about 3D printing. ("Smart guys!" Blair says to me.) I am introduced to a minister in the Rwandan government, who tells me how important Blair is, and says he knows nothing of his reputation back home.

I'm not surprised Blair wanted me to see all this: his AGI team is made up of smart, committed, inspiring young people, from all over the world, who have come here to try to do good. One night, while the boss is in meetings, I am invited to a team dinner at a Chinese restaurant. One of the AGI staffers asks me my sense of the public opinion of Blair in Britain. After a pause to consider how much I want to put a dampener on a very convivial supper, I decide to be honest: "Erm… they don't like him." There is much laughter.

"Well, we know that," says someone.

I'd misheard the question. What they were curious to know was how much people knew of his work now, and what they thought of it, not if he was personally popular. They had no illusions on that score.

I told them that I felt most people had no idea, really, of what he was up to, me included. What little we think we know — he makes lots of money advising dodgy foreign administrations — we are suspicious of.

The work of the AGI, too, is not without its PR challenges: Paul Kagame's record on human rights, for example. I asked Blair how he decided that, despite the allegations, the Rwandan President is a man worth working with?

"If the country hadn't changed for the better in the last eight or nine years — and even his worst critics admit that it has — then I wouldn't be here," Blair said. "If I didn't believe he was ultimately someone with the good of his country in his heart, I wouldn't be here. If I thought the people of the country didn't want him to stay in office, I wouldn't be here. If I thought he was a bad guy, I wouldn't be here.

"I'm totally in favour of the people who focus on human rights in countries like this," he said. "My purpose here is to try and help, and I'm not able to do that if I don't think the leadership of the country is well intentioned. That's not to say I'm oblivious to these issues. I will always raise those issues with the leadership, here and elsewhere."

Had he raised the issue of human rights with Kagame? "Of course I have," he said, "and he, by the way, will answer them very strongly, and say who is behind [the allegations]. To be honest, it is difficult for me to judge." He made the comparison with China. "There are completely legitimate criticisms of that system," he said, "but it is in everyone's interest that there is a stable evolution there."

Another accusation thrown at Blair is that his commercial work has at times become entangled with his philanthropic or not-for-profit work. One of Tony Blair Associates' offers was, as he puts it, "linking investors with opportunities". He knows, because of his travels and his contacts, which projects in the developing world need funding, and he knows private investors who might want to invest.

"We don't do that in Africa, not in countries where we are working [on a not-for-profit basis]." If a delegate at the World Economic Forum were to approach him now, in the hotel lobby, and say he wished to invest in development projects in Rwanda, would he connect them to a potentially profitable — and worthy — operation?

"You can't do it when you are embedded in the president's office," he said. "That would lead you into a conflict."

I asked him about the numerous allegations, over the years, that have been made about the blurring of distinctions between his philanthropic and his commercial work. "I cannot tell you how much bullshit there is," he said. "We can literally take it allegation by allegation. It's extremely important. The fact is, my sources of income were from the consultancies that have nothing to do with [his work in Rwanda, for example]."

Throughout these conversations, Blair was companionable and relaxed. As well as answering them, he asked questions — How's the magazine going? What have I made of my time with him so far? What else am I working on? Have I had a chance to get out and see the country? — and he encouraged people to talk to me. (Unsurprisingly, he didn't introduce me to anyone who said terrible things about him, but then those are not difficult to find; that part I could do without him.)

At the Marriott, our talk turned to more personal matters. Cherie had accompanied him to Kigali. I wondered if they had found time to enjoy themselves while they were here. Could they go out for dinner, or just have a look around the city?

"Occasionally we can," he said. "But it is pretty occasional. Not on this trip. She will come to the dinner we've got tonight but it's a working dinner."

Is it rare for Cherie to come on work trips?

"Reasonably, because I tend to be in and out. But I also try to make sure I spend time at home."

We talked about how he fights jet lag ("I take a sleeping pill if I have to"), his exercise routine ("I go to the gym most days; it gets more important as you get older"), and I asked about the psychological effects of his strange, accelerated existence, of life inside the bubble.

"You've got to keep, as I would say, control of your soul," he said. "Because otherwise you do become weird. You've got to realise that in the end you are never as important as you think you are."

He used to make a contrast between politicians and "normal people", the suggestion being he was among the latter. Does he still think so?

"You have to be very careful of that kind of self-analysis," he said. "A hundred people stand up and say, 'He's not normal at all!'"

Excerpts from an interview with Tony Blair, London, 15 September 2016 - Part Three

You have made a lot of money since you left office. Why is it necessary to make so much?

"Because otherwise you can't build your organisation. And I put a large amount of my money into the organisation. I've actually given away probably more than my net worth."

Can you tell me how much? Otherwise all people know is you get £2m a year from JP Morgan, and you've got big houses.

"Look, I've got to be very clear about this. For the first time in my life, in my sixties, I have enough money to have a nice house in London, a nice house in the country. That's absolutely true and I'm not saying I don't. Today, I've got a much higher standard of living than I've ever had. OK. All of that's true. However, I've put millions and millions of pounds that I've earned into running the organisation. I've given away, I think, in charitable donations, over £10m. If I wanted to make money, I'd spend my life making money. It's always difficult, this, because on one level, of course I've done well. The business has been successful. But on another level, what we've been able to do as a result of that is to build the infrastructure to allow us to do more not-for-profit work. Now I will maintain my personal consultancy [work] but otherwise everything moves into not-for-profit, and I will be gifting a substantial amount of money to that work. In the end, if people want to know what I'm actually doing and how I actually spend my time, they should go to the website and have a look at it. The rest, if they want to believe what they read in the Daily Mail or these other papers…"

I read some of it in The Times. In April, The Times reported that — I'm quoting here — you "use a secret trust to manage your multimillion-pound wealth". Is there a secret trust to manage your multimillion-pound wealth?

"No. What we have is an arrangement which allows us privacy. What [The Times] wanted to do, they wanted to write a story saying I was trying to avoid tax. It then emerged from their so-called undercover operation that everyone agreed not merely that there was no tax avoidance but that I'd actually instructed the people that set up my arrangements that there should be no tax avoidance. So, we employ no tax dodgers at all. I pay my full tax and I pay it on all my earnings, worldwide, even though I don't actually make any money in this country. Which, by the way, I should do."

Because your business affairs are more difficult to untangle than your charitable work, and because of the secrecy, that creates suspicion. Do you regret setting them up in that way?

"It's difficult. If I thought that in disclosing the information it would be properly used, I'd probably disclose more. But in the new arrangements we're changing all of that and so all of these structures will go. The business side will close."

Do you regret working as an adviser to the Kazakhstan government? Apart from anything else, it gave people another stick to beat you with.

"That's true. And that was difficult. And actually we haven't worked in Kazakhstan for a couple of years but I'm very happy to say why we worked there. It's important that people realise, Kazakhstan is a country that is wedged between Russia and China, a country the size of Europe that insists on being an ally of the West as well as having alliances with Russia and China. It's a majority Muslim country that is moderate, and the people we were working with there were really good, reforming ministers, and we were doing very sensible work there. But, of course, it turned into a big stick to beat us with."

Because it's an autocratic government and you are meant to oppose autocratic governments.

"Yeah. No, I understand that. But what is important to work out, if countries have tried to embark on a process of change, is: is it good to help them or not? And I think it is good to help them but I understand why it allows people to say, 'You're doing something you shouldn't be.' There were reasons we had for doing it. But we haven't worked there now for a couple of years."

If David Cameron were to ask you for advice on what to do now, what would you tell him to do, and not to do?

"I've definitely made mistakes since I left."

What were they?

"I think we allowed the money thing to become far too big an issue. We've had to spend our whole time persuading people that the complexity of the financial structure was not about tax avoidance when it obviously wasn't. And, also, I think you've just got to realise, to your point on working in Kazakhstan, that with something like that, however much objectively you can justify it, and it's sensible to do it, you're going to get a lot of criticism. But I think, as I've said to you before, what is difficult is people leave office young now. [Cameron is] leaving office even younger than I was. He's got at least 20 active years of his life yet. I mean, what's he going to do? If he makes money through speaking or takes certain positions, he'll be criticised for that."

To get to the Prime Minister's office in Jerusalem you must first pass through a series of security checks. Your passport must be studied at length, by three young women in black suits, who must talk among themselves, glancing occasionally in your direction and then returning to their whispered conversation. Then — in my case, anyway — you must be led outside into the sunshine and asked a series of questions about what you are doing in Israel by a girl who looks to be no older than 19. What is your business with the Prime Minister? Who booked your appointment? Who else have you met while you've been in the country? Where else have you been? Where are you staying? How long? Then the girl must go back inside and relay all this to a more senior woman, possibly as old as 22, and you must be taken outside again and asked more questions. Your passport must be taken from you, returned, taken from you again, and returned again.

At length, I was allowed to pass through the metal detector and into the building. The interior is not grand. It's functional, even a bit shabby. It could be any grey municipal building in a provincial town: the mayor's office in a Midwestern American city, perhaps.

After a wait on a sofa, and a coffee from the machine, I was led down a long beige corridor, small offices on either side, a large pot plant beside each one. At the end, on the right, a glass door led into a large outer office. Here, I placed my phone in a plastic basket. I showed my Dictaphone to the woman holding the basket and she nodded to say it was fine for me to take it into the room. "Good luck!" called out one of Tony Blair's staffers, as the doors opened. I took this to be a sign that I might need it.

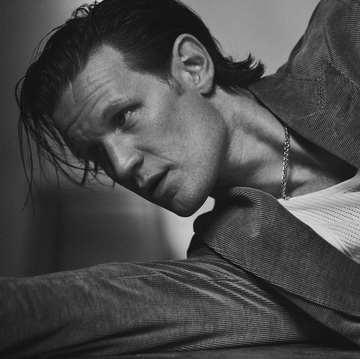

The office is not large. It is smarter, homelier even, than the communal parts of the building. I filed in with members of Blair's team and what seemed an enormous amount of aides, who lined up against a wall in front of a map of the Middle East. Simon Emmett, who took the photos on these pages, was with me, as he was throughout my trip to Israel, and he began snapping away.

Blair and the Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, were seated bilaterally, on leather armchairs, a circular glass-topped coffee table between them. Netanyahu is not a tall man, but he's solidly built. I felt that both Blair and I seemed slender and insubstantial in his presence. Blair's chatty good-blokeishness is designed to put people at ease, and it works like a charm. Netanyahu doesn't go in for that kind of thing. He was wearing a dark suit and a red patterned tie. We were all wearing dark suits and ties, even Blair, who rarely bothers with the neckwear. Blair introduced me and I shook hands with Netanyahu, who waved at some chairs that were arranged around a modest table. "Do what you have to do," he said, or something like that. I turned a chair round and sat near Blair, who nodded at me, and gave me a tense smile. I showed him my voice recorder and indicated I was about to press "record" but he shook his head as if to say "Probably best not to" — this was, then, to be an off-the-record briefing — and I said something like, "OK, I'll write it down." I'd been keeping notes in the other meetings, even when they were not for publication.

As Simon stepped forward to get his shots, Blair told Netanyahu, as he had told a number of his contacts here in Jerusalem, that Simon was a "world-renowned" photographer who lives in London, but that he was also an Israeli. Both these statements are true: Simon is indeed world-renowned, and he has both British and Israeli passports. Netanyahu didn't seem especially impressed.

He asked Simon if he speaks Hebrew. In Hebrew, Simon answered that he does. The Prime Minister spoke a short sentence to Simon, while rapping his knuckles, quite hard, on the coffee table. Then Netanyahu translated for me: "Do what you have to do, and do it fast."

We all laughed. My laughter was possibly slightly more forced. "So: ask," said Netanyahu. I wanted to know if he really thought that the plan for peace that Blair is promoting — a new framework for multilateral peace talks, involving the Arab states as well as the Israelis and the Palestinians — could work? Was he optimistic?

Netanyahu started to speak, quickly, in perfect English, and I began to scribble. (It's at moments such as these that I regret most my lack of shorthand.) He said that he felt more optimistic about peace than he had a year previously, and that he'd felt more optimistic then, than he had the year before that.

He then began to say flattering things about Blair's role in the process, about what an "invaluable partner" Blair is, and Blair, sensing that all this was definitely on the record and I wasn't getting it word perfectly, which was irritating, looked at me and whispered, firmly: "Turn your machine on!" I did, but Netanyahu had moved on to talking more specifically about the chances for peace.

Blair need not have worried. I'd written down what Netanyahu said about him. When Netanyahu had finished speaking, he glared at me. He told me I should feel free to edit what he'd said, but that I was not to change the sense of it. I said I wouldn't. Within 24 hours I was supplied with a transcript of the meeting.

(I debated whether or not to include that scene. It makes Blair's visit to the Prime Minister's office seem self-serving. And my and Simon's presence at it purely cosmetic: we were being allowed in only to record the fact that the meeting had taken place, that Blair has the ear of the Israeli Prime Minister, and that the peace talks are a real possibility, not only the fantasy of a man eager to repair his reputation. Then again, it happened, and it was quite funny, or I thought so — maybe you had to be there — and no doubt the joke, if there is one, is on me.)

What Netanyahu said was essentially the same thing that Blair and other contacts of his had been saying to me since I'd arrived in Israel three days earlier. I have edited it, as I have all the conversations in this piece, but not in a way that alters the substance of it.

He said that the conditions might be right to begin a new push for a broader Arab-Israeli peace and an Israeli-Palestinian peace. And that he shared Blair's analysis that the two are connected.

"There is a change in our region and in the world," Netanyahu said, "as many countries understand that Israel is not their enemy, but their ally in the battle against the twin forces of militant Islam — the militant Shiites led by Iran and the militant Sunnis led by Isis. And this creates opportunities for cooperation and for normalising relations between Israel and the Arab world.

"It used to be said that if we have a breakthrough for peace with the Palestinians, then we'd have a breakthrough for a broader Arab-Israeli peace. And that's certainly true, but more and more it looks like things could work actually the other way around — that by normalising our relations with the Arab world, we can harness these newfound relationships to bring peace between Israel and the Palestinians. And that is something that I've been discussing continuously and seriously with Tony, and with others in the region and beyond the region."

When Netanyahu had finished speaking and it was clear the interview was over, Blair and Netanyahu had their photo taken together in front of the map, and when that was finished I joined them there. Beneath the map was a glass case about the size of a shoebox. Inside it, Netanyahu told us, pointing at each in turn, were two objects: the first was a model of an ancient Roman arrowhead, the kind used to kill Jews during the destruction of the Second Temple in AD70. The other was a model of the Arrow, Israel's anti-ballistic missile. It looked like a child's plastic toy. That was their arrow, Netanyahu said to Blair, pointing at it again, and this is ours. The Romans, he said, are long gone from Jerusalem. "We're still here."

He said it in the way a twinkly great uncle might tell an old family anecdote. But I don't think anyone could have missed his point, and certainly Blair hadn't. Netanyahu's story was not an amusing one, and his point was deadly serious, but it seemed to demand a worldly response. Blair laughed, diplomatically.

It was Sunday morning, the first day of the working week in Israel. Blair had arrived in the country 48 hours earlier, on a night flight from Sierra Leone. His trip to Africa had included visits to a palm kernel oil processing factory in Liberia, discussions about energy with the President of Guinea, and a tour of the port at Freetown, Sierra Leone's capital.

Now he was in Israel, talking peace. This was his 32nd visit to the country in a year, I was told. (He seemed a bit shocked when I passed that titbit along.) It began at the offices of the Quartet on the Middle East, in East Jerusalem, the Arab part of the city. It was from this building that for eight years, until he resigned in 2015, Blair worked as the Middle East envoy of the Quartet (the UN, US, EU and Russia), his only official job since leaving Downing Street.

He had three meetings in quick succession: with a high-ranking figure of the Quartet; a senior Palestinian; and an expert on the region. (Not everyone is as happy as Blair and Netanyahu for their names to appear in the pages of a glossy magazine, for reasons that became obvious to me as the delicacy of their positions was explained, so as requested I haven't named them.)

We moved in convoy to the splendid King David Hotel, in West Jerusalem, through the fierce heat of the afternoon. Simon and I rode in the first of three Land Cruisers, with UN decals on their roofs. Blair rode in the second. We were accompanied by two of Blair's team, both Israeli women, as well as four Scotland Yard policemen.

The King David once housed the offices of the British Mandatory authorities of Palestine, and was famously bombed, in 1946, by the Zionist paramilitaries of the Irgun. Here, in the basement, Blair met Dore Gold. (It's pronounced Dory, as in Finding Dory.) Gold is an urbane, moustachioed man, expansive in both conversation and waistline. A veteran Israeli diplomat — American by birth and education — Gold was at one time the Israeli Ambassador to the UN (not, I sensed, a popular organisation in the country) and has been a close adviser to former Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon and to Netanyahu, who has recently made him director-general of the Foreign Ministry.

Like the others we met, Gold was cautiously encouraging about the possibilities for peace. He said that the new framework for negotiations that Blair was promoting was worth trying.

"The opportunity is obvious," he said. "Whether it is seized or not."

No matter whom he met, Blair exuded a sort of controlled bonhomie. He was friendly but not familiar, informal but respectful. He made everyone feel important, he made even me feel (almost) important. He continued to introduce Simon as a "world-renowned" photographer, which made Simon feel good, and also everyone else in the room feel good, because it's pleasant to feel that one is participating in events that justify the presence of a "world-renowned" photographer. One foreign ambassador to Israel beamed like a competition winner.

On the hour-long drive back from Jerusalem to Herzliya, an affluent coastal enclave north of Tel Aviv, where the Blair group was booked into the Ritz-Carlton hotel, I sat on a bench seat in the back of our Land Cruiser and stared out of the window. We sped past mountains and valleys, past palm trees, past Palestinian towns on one side and Israeli towns on the other, the former quite clearly less prosperous, by many degrees, than the latter. The setting sun shone softly and pinkly on both, without discrimination.

The next morning, in his suite overlooking the beach and the sparkling Mediterranean, in chinos and a light blue shirt the same colour as the cloudless sky, I asked Blair what exactly he was doing here in Israel, given the fact he no longer has an official role.

He took me through the history. During his time as prime minister, he said, he had some involvement with the issue of Israel and Palestine. In 2007, he decided, as he prepared to leave office, that he would take on the building of Palestinian statehood as one of his causes, hence his appointment as envoy for the Quartet. There were negotiations over what his mandate would be, and ultimately it was non-political. "That became an inhibition, frankly," he said. To the press and public, Blair had been sent to Jerusalem to bring peace to the Middle East — or something. Actually, his job was less ambitious, though perhaps not that much less difficult: he was to work with the Palestinian Authority to build the Palestinian economy in the West Bank and Gaza. Eventually, he found that having no say in the political situation meant that his efforts were stymied by circumstances beyond his influence.

"I ended up in a situation you should never be in in politics," he said, "which is responsibility but not power. I mean, having power without responsibility is great but having responsibility without power is not very sensible."

The reason, in Blair's view, that peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians is not just desirable — for obvious reasons — but potentially transformative is that "if you manage to make peace between Arabs and Israelis, you strike a huge blow for cultural acceptance and for peaceful coexistence. Alternatively, if it ends up in conflict and dispute, you give power to those elements that are extreme.

"It's not just a territorial issue," he said of Israel-Palestine. "It is in part a conflict about cultural acceptance. It has implications for the world."

I asked him again to explain to me exactly where he fits into all this.

"My role is that I have established relationships in the region. From the first months I came here, people said, 'You'll last six months.' Well, I'm still here. 'You'll last a year.' I'm still here. After I left the Quartet they said 'That's it, he's off now.' I'm still here."

"What's been very strange since leaving the Quartet," he added, "is that, because I don't have an official position, it's actually easier for me. People feel able to be more frank. And so what I do is, I work on how this [process] might be put together. And I think there is a general desire to have [the Arab nations] involved now."

Blair began to talk about the new leaders in the region — in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the UAE, Qatar — and how sensible and dynamic they were, and how much they wanted to support the new framework for peace, and how the stars were aligning for a solution.

I looked around at his suite, the balcony overlooking the beach. Who pays for this room? I asked.

"I pay for it in part," he said. "But it's raised money. I have to raise money."

This isn't a charity project, what you're doing here?

"Well, it's not in a formal, legal sense, it's not. And I suppose actually it will be, in the end."

"We're almost there," said one of Blair's team.

Excerpts from an interview with Tony Blair, London, 15 September 2016 - Part Four

You don't have to do any of this stuff you're doing now. No one is forcing you to do it. It's not like if you don't do it, everyone's going to go, 'Why the hell isn't Tony Blair out there fixing the Middle East? It's up to him to sort it!' So, this is entirely your choice. The question is: what makes you do it? Why are you doing it?

"Because I think I've got something to contribute to a thing that is important and because if you've spent most of your life trying to make a difference in the world you want to carry on doing it."

A cynical man would suggest that also you're atoning for something…

"No."

Or that you feel a sense of responsibility because you were one of the main players in how the world has come to this point.

"That's a slightly different thing. I do feel a sense of responsibility. And my interest in doing things around the peace process in the Middle East, yes, is in part as a result of my experience in government. But it's also because I think, again rightly or wrongly, that I have, as a result of my experience, a way of looking at these issues — development, extremism, Middle East — which is different and where I believe that the policy has to change. And, you know, we're still building this whole organisation. A lot of people won't think this way at the moment because most people just read about [his personal wealth] or about Iraq or so on, and don't actually understand what I'm doing now. But I think we will in time build this organisation into something really significant. But we will see."

Others would suggest you are doing what you're doing because you hope to repair your reputation.

"No."

Instead of the guy who invaded Iraq, you could be the guy who fixed the Middle East peace process. Which would be better.

"No, it's not to do with that. It's to do with the fact that I'm really interested and I think I've got something to contribute. I think what's interesting, for example, about the Middle East, is, I would say, this debate and activity that I've developed around the possibility of a new relationship between Israel and the Arab world. I think increasingly it is being accepted as the most sensible way forward. Now, I will only ever play a part in that but that's where I think I can make a contribution and that's why I do it. And because I think it is connected to this wider issue of extremism, since I think you will never defeat this extremism unless you fix the Middle East. And it will be fixed, by the way, in the end. People look at it and say it's hopeless. No, it's not, it's undergoing this agonising process of transition but in the end what will emerge, with whatever difficulty and however much turmoil there will be in the meantime, what will emerge will be something much better."

I've followed you around a bit. Your life is extremely circumscribed by your position. It's a beautiful day outside. The rest of us can go for a coffee, or wander in the park for a bit, sit on a bench and read a book. You can't. Do you miss that?

"I do miss that. But it just comes with the territory, doesn't it?"

Do you ever think about how you could have taken a different path? You chose this life, you could have chosen another.

"Sometimes, I do think, 'What would have happened if I had taken a different path?' I don't think I would ever have stayed a lawyer. I might have done other things, and I'm still very interested in learning and thinking and writing about other things. I'm very interested in concepts of faith and issues to do with religion. I've always been really interested in that. But right now I'm very focused on the centre ground in politics and how it recovers its energy and vitality."

You'll soon have been the former prime minister longer than you were the sitting one. You've said that you enjoy your new life more than you enjoyed your previous one.

"I always found it a bit odd when people talked about 'enjoying' being prime minister. I think some people do, by the way, but I would never describe it that way. You have a huge sense of purpose but I found the decisions of such magnitude that it was hard to enjoy it very often."

How would you describe it? Fulfilling?

"Yeah, definitely. You're taking big decisions and running a country so it's exciting in that sense, but…"

And now?

"It's less stressful."

Before he was elected prime minister for the first time, before 9/11 and Afghanistan and Iraq and everything else, Tony Blair seemed to some of us like one of us. Not everyone, by any means, but many people in Britain were persuaded by him. That's why he won three consecutive general elections. The thing about seeming to be one of us and turning out to be one of them — if that's what happened — is that it's worse than if you'd obviously been one of them from the beginning. It feels like a betrayal. It stings. And that perhaps explains some of the fury directed at Blair, even before you arrive at the specifics of Iraq and so on.

To some he will always be "Tony Bliar", venal pocket-liner. To many, he is discredited, at best. All this has to hurt, of course, on a personal level — Blair is a charmer, someone who likes to be liked — but perhaps more damagingly, in his eyes, it means that, for now at least, his brand of politics is tarnished by association. The centre ground, here and elsewhere, is in retreat, and the extreme fringes are in the ascendant. (Whether you think this is the fault of Blair and his generation of leaders or not, unless you are yourself of the far left or the far right, it's hard to feel much sense of triumph about it.)

When we talked in Israel, I alluded to the fact that Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton are the least popular presidential candidates ever in the US, and said what an indictment that was of contemporary politics.

"And you can go right round the world on that," he said.

And in the UK?

"Well," he said, "in the UK at the moment you've got a one-party state."

Yes, I said, and the leader was not elected.

"When you put it all together," he said, "there's something seriously wrong."

In London, I asked about Jeremy Corbyn, and the way the hard left has taken control of the Labour Party, all but erasing the work Blair and his inner circle had done, over many years, making Labour the party of government. It was as if New Labour had never happened.

I asked him if he could take Jeremy Corbyn seriously as a potential prime minister?

"This is not about Jeremy Corbyn," he said. "It's about two different cultures in one organism. One culture is the culture of the Labour Party as a party of government. And that, historically, is why Labour was formed: to win representation in Parliament and ultimately to influence and to be the government of the country. The other culture is the ultra-left, which believes the important thing is to raise the consciousness of the people, that believes that the action on the street is as important as the action in Parliament. That culture has now taken the leadership of the Labour Party. It's a huge problem because they live in a world that is very, very remote from the way that the broad mass of people really think."

Blair was on a roll now. "The reason why the position of these guys is not one that will appeal to an electorate is not because they're too left," he said, "or because they're too principled. It's because they're too wrong. The reason their policies shouldn't be supported isn't because they're just too wildly radical, it's because they're not. They don't work. They're actually a form of conservatism. This is the point about them. What they are offering is a mixture of fantasy and error."

On 24 September, Corbyn strengthened his position by defeating a challenge to his leadership. The following day I spoke to Blair on the phone. He was in Los Angeles, raising funds for his work in the Middle East.

I asked how he felt about Corbyn's victory. He said he felt the same way now as he did before. "Frankly," he said, "it's a tragedy for British politics if the choice before the country is a Conservative government going for a hard Brexit and an ultra-left Labour Party that believes in a set of policies that takes us back to the Sixties."

I wondered if he wasn't now questioning his decision to keep quiet during the leadership contest? "I don't think it would have made any difference at all," he said. "Certainly if I'd intervened for [Corbyn's challenger] Owen Smith it probably would not have helped him. In fact it wouldn't have helped him. That's just the reality." In other words, so unpopular is Blair even in his own party, the one he led to the greatest electoral successes in its history, that if he were to take a position in a debate it would damage that position, as a direct consequence. I asked if he could ever see a time when there would be a formal role for him in the Labour Party, or in British politics?

"I don't know if there's a role for me," he said. "But I've got views and I've just expressed them to you. I guess I'm entitled to speak. It's a free country."

What, I asked Blair, will his legacy be?

"My Lord," he said. "That's one of those..." He ummed and erred for a while. "I think it's too early to say, actually," he said. "I know that sounds a bit of a..." He tailed off. Then started again. "I don't like talking about my own legacy," he said. "Everyone's got their own opinion."

"I don't know," he said. "I could write you an essay on it, but..."

For a very brief moment, he sounded almost defeated. But then he rallied, as he tends to do, and he began to spell out all the positive things he felt he had achieved while he was in office, and of course there are plenty of those, some easy to explain — the introduction of the minimum wage, peace in Northern Ireland — others harder to measure, such as what he describes as a more tolerant society, with less prejudice, more equality of opportunity. And he went on for a while from there.

"Playing my part in all that was, I hope, what the legacy will be, but who knows?"

Still, when he looks at the political situation now, it's hard to imagine he doesn't feel dismayed?

"Obviously," he said, "there's been this huge reaction against the politics I represent. But I think it's too soon to say the centre has been defeated. Ultimately

I don't think it will be. I think it will succeed again."

He doesn't feel deflated or depressed?

"Mostly I feel motivation," he said. "The centre ground is in retreat. This is our challenge. We've got to rise to that challenge."

I tried again. What is his role going to be in this? Can he see himself returning to politics in some way?

"There's a limit to what I want to say about my own position at this moment," he said. "All I can say is that this is where politics is at. Do I feel very strongly about it? Yes, I do. Am I very motivated by that? Yes. Where do I go from here? What exactly do I do? That's an open question."